As The Volume of Street Style Diminishes Due to Covid, We Look at How Street Style Will Evolve

By Angela Baidoo

Over the last nine months, anyone that makes their living from the fashion industry can’t help but have noticed the steady decline in street style content. A lucrative sub-industry of fashion week has been one of the many casualties of the global lockdowns caused by the pandemic.

The modern-day phenomenon that is street style has come in for sharp criticism in recent years. Despite its popularity – due to its ability to generate masses of content for magazines, social media, and influencers over the space of four weeks.

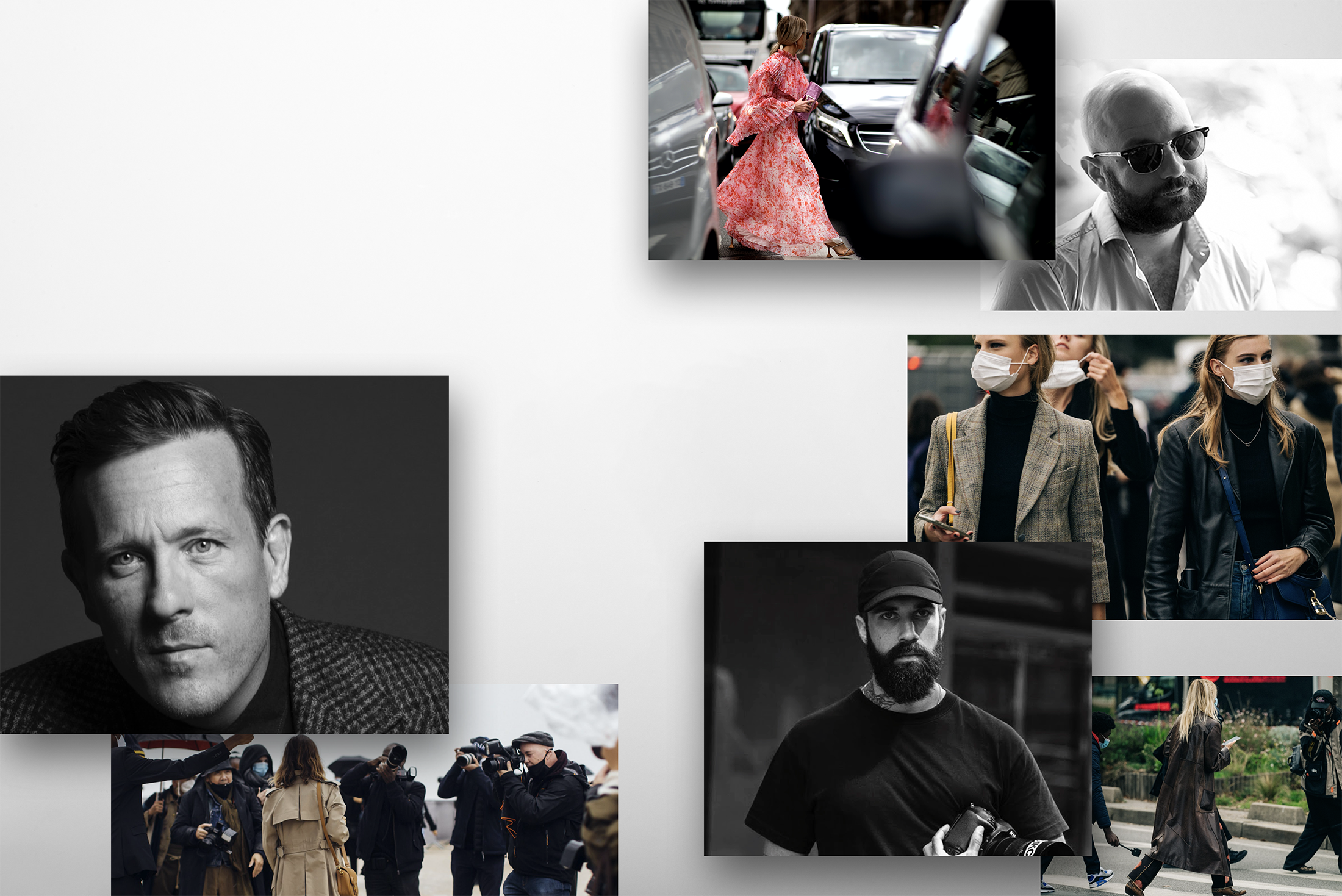

As questions are finally being asked of the runway system itself and whether it needs to re-set, the same hard look needs to be considered for the street scene. From its unregulated brand sponsorship deals to its lack of inclusion, as Adam Katz Sinding – a long-time photographer of fashion week explains:

Street style as a genre must adapt and inevitably change. I personally would not mind a bit of a toned-down mood at fashion week. We work our asses off just to keep up.

– Adam Katz Sinding

Now hybrid runway formats are steadily gaining traction, as luxury brands such as Gucci experimented with film in November with its week-long Guccifest event, and Balenciaga’s Afterworld video game launch in December, being two prime examples. If this trend continues, what is likely to happen to the street style scene? And how will it maintain its relevancy in an industry reeling from cultural, financial, and moral reckonings?

Setting the ‘Street Style’ Scene

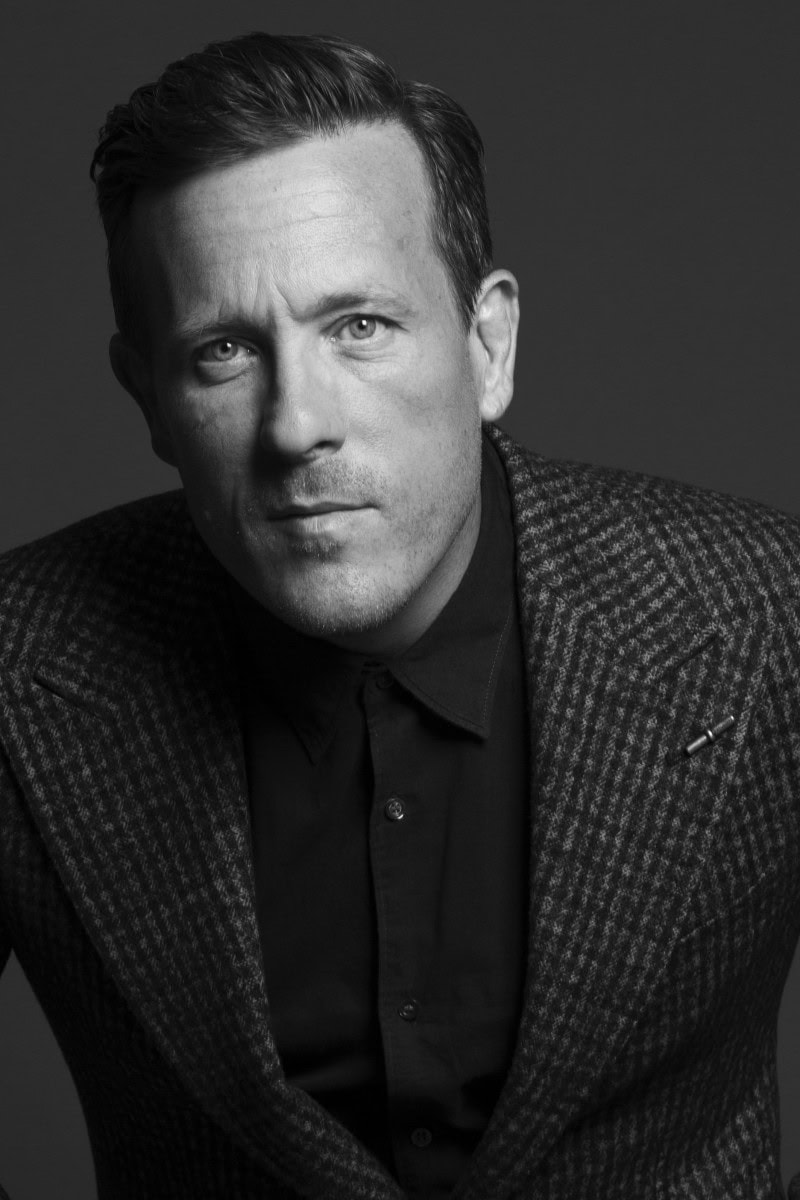

Those who work within the industry often feel that street style is not an accurate catch-all for what is typically worn to fashion week. Not when those invited to shows are in their best-dressed Prada, Céline, or Comme des Garcons, which are not what would be considered an everyday look on the street. Renowned photographer Scott Schuman, who has been capturing authentic street style on his blog The Sartorialist since 2005, put it more succinctly when he said

One of the things I’ve always been frustrated with is that the media has decided that street style is what people wear to fashion shows….. and that’s not street style, that’s fashion week photography, which is an eco-chamber… real street style is what people are really wearing on the streets.

– Scott Schuman, The Sartorialist

The Sartorialist, alongside Collage Vintage and Style Du Monde, were but a few of the blogs that significantly impacted contemporary fashion, from magazine editorials to high street designers seeking inspiration. They introduced a generation of creatives to new styling ideas beyond the polished top-to-toe look that was seen on the runways.

The ordinary people on the street captured on these blogs often mixed tropes from different subcultures, influenced by sport, music, or cultural movements. Ralph Lauren polo shirts were paired with camouflage cargo pants and pumps, or thrift store layering would combine tea dresses and slouchy cardigans with wool tights and chunky stacked heels.

There was also the more-is-more maximalism of Japanese fashion, which was recorded by the self-titled ‘Street Fashion Photographer’ Shoichi Aoki. Starting in 1985, Aoki founded three major publications – Fruits, Street, and Tune – to document the style of Japanese teens. More than a magazine, it was the first pre-social media introduction to the fluoro-coloured saccharine sweet world of the Harajuku youth, whose influence can still be felt in the styling of brands today, from Gucci to GCDS. Much like its western counterpart this scene has also become a victim of over-saturation from big brands and homogenous trends such as Normcore.

As we advance, what will be the purpose of the fashion week street style image if the original spark that made the scene so influential has burnt out? Caused by the commodification of the scene, triggered by the innumerous brand partnerships with influencers and celebrities, resulting in the big four cities mirroring each other in their aesthetic. The answer is still up in the air, but there are still several ways the scene can survive and regain its relevancy in the new normal.

One Bottega, Two Bottega, Three Bottega, Four . . .

Once upon a time, it used to be that the streets would inform designer collections in a ‘trickle-up’ scenario. Fashion and Costume Historian Shelby Ivey Christie highlighted how the Neo-Soul aesthetic of Lauryn Hill inspired John Galliano’s Dior collection for Spring 2000. Yet, not until recently have brand marketers been so focussed on facilitating the process of major fashion houses feeding, or to put it more accurately, flooding the scene. Thus, creating a repetition system that artificially inflates the popularity of a product by increasing its exposure.

It has often been a topic of conversation in opinion pieces on street style that the sub-industry has become an eco-chamber. Referencing how the sidewalks were becoming sponsored by brands such as Balmain, Bottega Veneta or Dior, with influencers wearing gifted looks in a monolithic way. As Nick Leuze, a fashion photographer who has worked with WWD and The Impression, observed in his work, “It was getting very stale for sure. Bottega Veneta was maybe the epitome of that, but you could already observe this change for quite a bit.”

In 2018, the Italian brand’s resurgence went into overdrive, with Céline Alumni Daniel Lee’s appointment as Creative Director of Bottega Veneta. He immediately set about re-igniting fashion’s love affair with accessories – often the backbone of luxury brands’ revenue. It was only a year ago, during fashion month in September, that shopping platform Lyst saw searches for “Bottega Veneta shoes” increase by 156%, surging to 27,000 searches a month at its peak. Bottega Veneta then had its position as one of the industry’s most sought-after brands confirmed when the sheer number of converts in the labels signature quilted or woven ‘Lido Intrecciato’ mules paired with its leather culottes and an oversized blazer became the go-to uniform on the streets of Milan and Paris. Worn by the likes of Mytheresa Fashion Buying Director Tiffany Hsu and Content Creator Erika Boldrin.

The aggressive growth of the scene’s business side is a telling barometer of the ‘Look at Me’ culture spawned by social media platforms like Snapchat, Instagram, and now Tik Tok. Brands that would have previously focussed solely on what was taking place behind the show venue’s closed doors have pivoted to embrace the copious amounts of free publicity, amplification, and social media engagement that outfitting the right influencer can bring.

Before I was doing this, the brands didn’t really know what to do. They wanted to control it, now they’ve gone completely the other way, and they’re giving clothes out to everybody. You go to a Fendi show, and it’s a total echo-chamber because you’ve got all the influencers sitting on the front row (wearing the collection), and I think it makes it less interesting.

– Scott Schuman, The Sartorialist

Pay to Play

This shift has been a long time in the making, with the seeds of change being sown in traditional media over the last decade. Major glossy fashion magazines’ editorial shoots would often feature looks styled from a single brand, i.e., ‘Cashmere tank top, Shirt, and Wool trousers. All Marc Jacobs’. It served as an effective method of keeping advertisers happy. Still, it sacrificed the stylist’s point-of-view and offered little inspiration to the reader, to see a look replicated by numbers from the runway show.

As former British Vogue Fashion Director Lucinda Chambers opined in an interview following her departure from the magazine, “Oh I know [my shoots] weren’t all good – some were crappy. The June cover with Alexa Chung in a stupid Michael Kors T-shirt is crap. He’s a big advertiser, so I knew why I had to do it. I knew it was cheesy when I was doing it, and I did it anyway.” Former Harper’s Bazaar Fashion Editor Chrissy Rutherford also took to her Instagram at the beginning of December to discuss another of the industry’s well-known flaws.

Journalistic integrity went out the window a long time ago like brands are literally buying covers, they’re buying features, they’re buying every single page, that’s how magazines are alive today, and so editors are forced to prioritize those brands….[Brands have a lot of power, and their money is how magazines can stay afloat].

– Chrissy Rutherford, Fashion Editor

Advertisers can also capitalize on the fact that images captured by street style photographers can be featured throughout the year when they are tied-in with affiliate marketing campaigns or click-through shoppable content that will drive traffic for months after fashion week.

Breaking Away from The Top 10

A quick scroll through the street style galleries of Vogue, Glamour, Elle, or Grazia throws up evidence of the glaring omission of a more diverse range of showgoers that is often not reflective of today’s modern society. It can be argued that the photographers who cover the streets at fashion week are not photojournalists capturing everyday life in the city. But the reality remains that they have a remit set out for them by the editors of the publications they are working with. More often than not, this requires them to capture those top 10 faces that will result in the most engagement and social media clicks.

The landscape during fashion week has been slow to diversify. Though there is pressure to meet the demands of the job, it can be an impossible ask for photographers to be expected to reflect an industry that has still not moved the dial far enough beyond a black square, a few Diversity and Inclusion hires, and an annual membership to an accountability initiative. Evident from how only a handful of BIPOC attendees are photographed excessively from city-to-city. Think Tamu McPherson, Lindsay Peoples-Wagner, Chrissy Rutherford, Shiona Turini, Nikki Ogunnaike, Michelle Elie, and model Adesuwa Aighewi, to name a few.

It’s not their fault they’re doing their job….. how can you shoot a bunch of diverse people when the magazines aren’t hiring them, or the brands aren’t inviting those people [to the shows].

– Scott Schuman, The Sartorialist

The genre has remained stagnated in a mostly white, model-thin view of who gets to be deemed cool. With the notable exception of Teen Vogue, whose Editor Lindsay Peoples-Wagner took the lead to diversify the street style galleries on their digital platform. Stating, “We pledged to stop merely lamenting the lack of diversity and to start leading the charge to showcase it.”

After a year of fashion brands pledging to do better due to the resurgence of the Black Lives Matter movement, further opportunities need to be extended to BIPOC influencers to attend or expand their attendance shows. Influencers such as Amanda Murray (@londongirlinnyc), Ellie Delphine (@slipintostyle), Grace Ladoja (@graceladoja), Terence Sambo (@terencesambo), and Jean-Jacques N’djoli (@ndjolijean). Meaning that they can now seek greater monetary compensation for their content via bigger brand partnerships.

Change may yet come from inside the industry itself, as many more men and women of color gain a foothold on the upper echelons of magazine mastheads, and in turn, hire more diverse teams. The hope is that this will then be reflected on the seats and streets at fashion week.

Embracing The Everyday

The appetite for endless streams of content, caused by a period of downtime spent behind closed doors, has seen brands long concede to the fact that they need to feed the beast. But there also needs to be an open conversation around the adoption of a slower way of consuming content, for capturing the anonymous, that can still be inspirational. In the summer, when Schuman took a spontaneous image of a girl holding her dog whilst riding a skateboard, it racked up over 30,000 likes. Speaking with fashion photographer Vincenzo Grillo, he shared the same viewpoint.

It’s the more genuine genre of streetstyle. You can be a fashion icon even if you’re not a guest of a fashion show. Around the world I found my biggest inspirations and a lot of times I found them far from the catwalk!

– Vincenzo Grillo, IMAXtree

This year has been one of such momentous societal change. Ten years from now, we will ask how ordinary people on the street reacted to the pandemic through their outward appearance? Did New Yorkers adopt an all-black uniform of Rick Owens to reflect an apocalyptic mindset? Or did Italians cocoon themselves in cashmere sets and Moncler goose-down jackets?

Schuman was one such photographer who continued to go out on his bike to record what was happening on the street, despite knowing that fashion was the last thing on New Yorkers’ minds.

The biggest thing, at least in New York, is that there was hardly anyone on the street…. it was a good example of people just not having their minds on fashion. Because fashion is a luxury. I’ve grown up in fashion, and you hear designers talk about this apocalyptic woman who becomes a warrior, but nobody is doing that. Nobody is becoming a warrior; everyone is becoming a potato.

– Scott Schuman, reflecting on the last nine months

Another veteran photographer of the scene, Adam Katz Sinding, who has a long history of documenting cities – from Tokyo to Sydney – takes his relationship with the scene with a pinch of salt. His first book was titled ‘This Is Not A Fucking Street Style Book.’ Sinding, speaking in early December, could sense the change in the genre that many others were already starting to recognize, stating, “Street style has reached its zenith, and is on a downward trend, which is fine…..the nice thing about it for me is, I started doing it for free in Seattle for myself, so I’ll continue to do it even if it doesn’t become lucrative in the way that it has been.” This perspective speaks to the fatigue being felt in all corners of the industry and the desire to go back-to-basics.

Re-Defining The New Masculinity

In the face of a new wave of lockdown measures that makes it seem rather premature, it’s still an encouraging sign that the Camera Nazionale Della Moda Italiana and the Fédération de la Haute Couture et de la Mode have announced they are forging ahead with their dedicated men’s shows in January (an indication of the sizable market share of menswear in their regions). In contrast, the Council of Fashion Designers of America, alongside the British Fashion Council, recently decided to fold their men’s weeks into their women’s events, pushing the start of their seasons back to February.

Whether in Tokyo or Paris, the menswear street style scene has always projected an air of sartorial freedom, which makes it a more exciting prospect to cover and grow going forward. Taking London as an example shows mainly occur in and around the buzzier end of Shoreditch, at the Truman Brewery in East London, which tends to attract a naturally more diverse street style crowd. Admittedly the ensembles will be heavily skewed towards streetwear and sneaker culture, but in recent years a trend that has gathered momentum is blurring gender lines. As showgoers pair Dior Saddlebags with their utility pants, style pearl necklaces with polo-neck sweaters, and adopt sheer layering. Reflecting the changing view of masculinity being seen on and off the runways, championed by designers from Bianca Saunders to Charles Jeffrey Loverboy.

As brands from Valentino to Etro decide to incorporate their menswear offer into their women’s runway shows, the womenswear will inevitably be the main focus for buyers and editors, risking menswear getting lost in the noise. “I think it’s going to hurt menswear because obviously, it’s going to be overshadowed by women’s, and if you’re just a menswear brand, how are you going to fight against these bigger women’s brands,” says Schuman.

Granted, this comes when brands are consolidating their finances, but they also risk undoing years of progress. Especially when the dedicated fashion weeks of the big four have generated such a buzz for the market, which has been building year-on-year since Kim Jones and Virgil Abloh made their respective debuts at Dior Men and Louis Vuitton.

There are also fewer opportunities for menswear brands to showcase themselves outside of the frame of streetwear or traditional tailoring. A dedicated week would allow for brands such as Ludovic De Saint Sernin, Casablanca, or Martine Rose to gain much-needed press.

When a brand decides to show their men’s and women’s together during women’s week, a lot of those men’s editors aren’t coming back, and so men’s get much less coverage than if they would have kept it in men’s…Men deserve to have their own time to shine.

– Scott Schuman

The men’s showcase needs to continue receiving investment and support from the governing bodies and international press to grow as a platform by continuing to show in its dedicated slots in January and June. This will further elevate the men’s street style scene that is known for being more dynamic. As showgoers, look consist of a true high-low mix, from an Aquascutum trench coat worn with a baby pink hoody, classic 501s with oversized button-down shirts, or Fred Perry polo tops with diamond-encrusted Takashi Murakami flower chains. The luxury fashion houses are often over-represented in the accessories category. Still, they equally so are the latest Nike collaborations – where you can take your pick from Sacai to Dior Men and Travis Scott.

This re-focus on menswear can address the imbalance of street style content produced for fashion media’s digital platforms. The fact that the women’s galleries feature hundreds of images for each city, yet the men’s galleries at most major consumer fashion publications such as GQ & Esquire averages out at fifty images, makes a compelling argument to redress the balance in the future.

Regaining Relevancy

The street scene will eventually evolve, as it’s still an important cog in a very big wheel that is a billion-dollar business, and the recent return to physical fashion shows is testament to that. Fashion week itself will always remain a lucrative revenue stream for photographers, but the pause from the pandemic has given a number of key players food for thought about life after street style. Grillo acknowledged “Fashion is my first love for sure, but the ability to re-create myself and my work is my biggest challenge…….The opportunities to create original contents are stronger than any virus.” Going forward every facet of the industry, will need to justify its place in the new normal, and the street style scene is no exception. It makes sense then, that the producers of these images are instrumental in its – slow, but inevitable – evolution.

Having always served as a way to bring runway trends to a mass audience – by showing how a look can be dissected and broken down for everyday wear – street style can sustain its relevancy by seeking out and promoting new faces, from diverse backgrounds, with a unique style to reflect the changes the industry has been so vocal about committing too. Pivoting into the growing menswear market, not just across the big four, but on a global level – from Seoul to Lagos – where men are pushing the boundaries through fashion; and elevating the every day, as influencers have spent their time in lockdown turning their cameras on themselves to continue producing spon-con, it proves there is an appetite for original, authentic, relatable content, that could see street style return to an updated version of where it first started.