The Irish designer leans into play and proportion — bumsters, haystack temples, and a raw Y2K spirit — as McQueen’s new voice finds his stride.

By Kenneth Richard

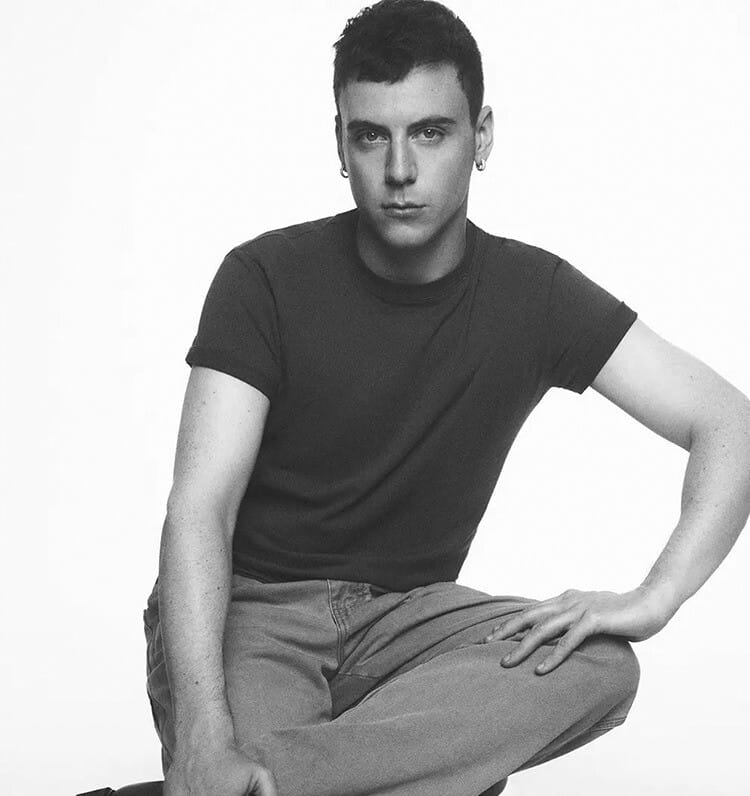

Backstage at McQueen, Seán McGirr wore a faded button-down, the collar softened by wear, his newly grown shaggy hair falling into his eyes. When he smiled — which he did often — it came with a sincerity that instantly disarmed. In those small gestures, you saw a designer loosening his grip, leaning into play.

The set echoed The Wicker Man: haystack temples rose across the runway like ritual monuments, a surreal echo of pagan ceremony. By the finale, the models themselves broke into cheers — a rare, unguarded celebration of a collection that carried them as much as it carried him.

McGirr, born in Dublin in 1988, studied at Central Saint Martins before graduating with an MA in Fashion in 2014. He cut his teeth at Dries Van Noten and Uniqlo, later serving at Burberry and Vogue Hommes Japan, before becoming head of ready-to-wear at JW Anderson. In late 2023 he was appointed creative director of Alexander McQueen, his first three outings shown as co-ed collections. This season marked his first dedicated women’s show.

When asked about reviving the bumster, McGirr explained how he tested the waters with friends and models. “Is it too low?” he asked them. The response came back unanimous: lower still.

For him, the silhouette was less about provocation than about energy, tapping into what he described as the “febrile” mood of summer — nights at gigs, metal festivals, and that sense of instinctive abandon.

The collection carried this looseness in construction. Washed fabrics twisted tightly across torsos before falling apart around the hips. McGirr coined the term “soupy” with his team — “snatched on top, relaxed below” — as a way to describe that mix of structure and ease. It was a language of imperfection: a jacket meant to look pulled from a flea market, garments designed to feel “lived in” rather than pristine.

References to the 1990s, and to McQueen’s own archive, ran throughout: the boots lifted from Spring 2003, makeup steeped in Y2K energy, the set design as much about ritual consumption as fashion. Makeup artist Daniel Sallstrom’s pink-rimmed eyes and lived-in skin tones mapped the arc of The Wicker Man, from outsider to initiate consumed by nature.

Nudity too was intentional. “It was important — celebrating women’s bodies,” McGirr said. Tops fell open, fabrics clung, nipples visible beneath washed materials. The effect was raw yet celebratory, aligning with his belief that fashion should feel instinctual rather than over-intellectualized. “Sometimes you feel buttoned up, sometimes it’s about zipping it all down. It’s just a feeling.”

What emerged was the strongest stride yet from McGirr at McQueen — more elevated in concept, more assured in construction, and undeniably more playful.

His willingness to bring back the bumster, a silhouette central to Lee McQueen’s early vocabulary, felt less like nostalgia than a declaration: that extremes still have a place here, that daring can also be joyous. The bumster’s return signals not just a revival, but a reckoning — a reminder that in McQueen’s world, the line between provocation and liberation has always been worn low.