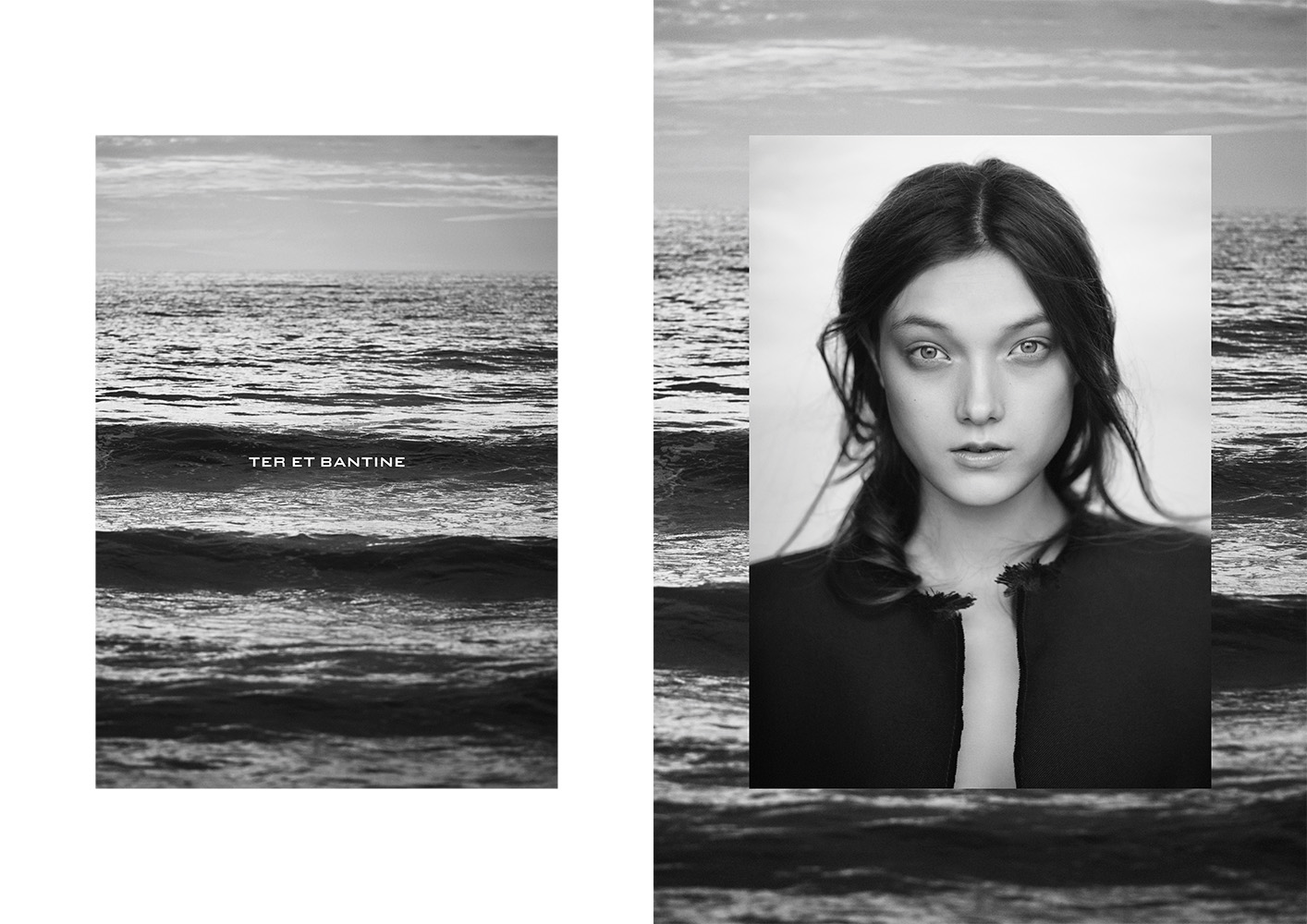

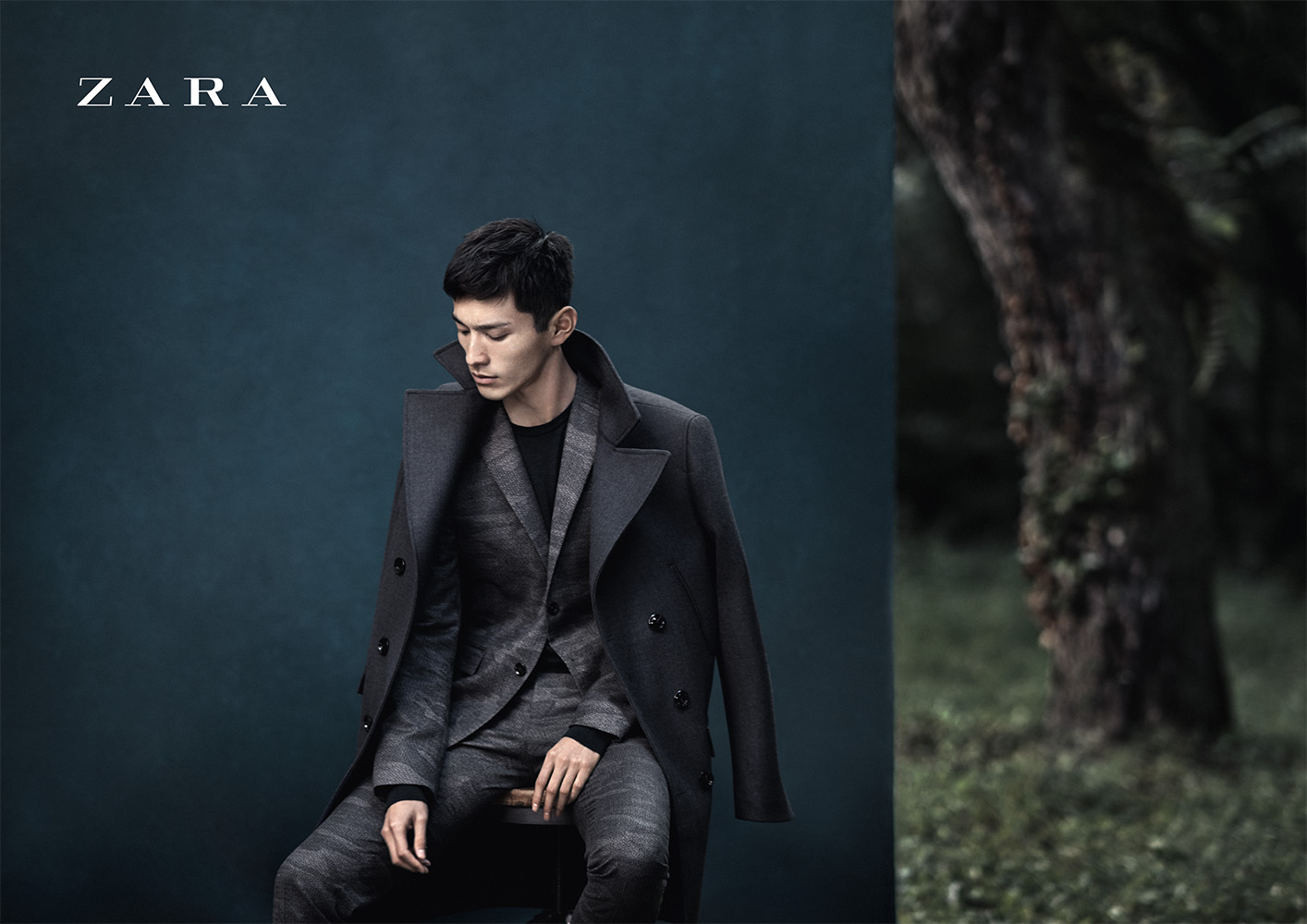

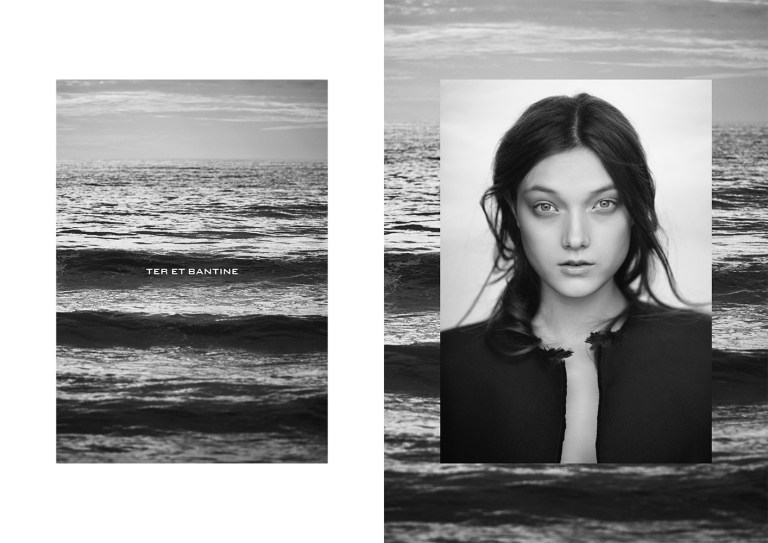

No man, or brand, is an island. And while plenty of brands position themselves as the voice of a singular person, truth be told, their success is due to the combination of players who helped to champion them to greatness. These champions often labor behind the scenes, building teams behind the team. One such champion is Alan Aboud of Aboud Creative, who, for over the past 25 years, has built lasting creative partnerships with the likes of Paul Smith, Levi’s, Zara, River Island, DL1961, and Ter et Bantine, to name a few. Those partnerships have resulted in creative that has not only served those brands on their rise, but at times transcended the fashion arena to reach into popular culture.

The Impression spoke with Aboud about London’s back streets, the difference between men’s and women’s, big ideas, brands as publishers, the digital age, The English Beat, and that iconic stripe.

Kenneth Richard: Alan, nice to chat again and looking forward to hearing more about how it all came together for you and the agency. How did you get your start in the industry?

Alan Aboud: I went to an art school in London – St. Martin’s School of Art, which is probably much more famous for fashion than for graphic design. St. Martin’s had two locations, one in SoHo and the other in Covent Garden. I went to Covent Garden, which basically backed onto a street called Floral Street, and that was where Paul Smith had his main London store.

When I was graduating in 1989, at our end of the year degree show, a representative from Paul Smith came and had a look at my work and said that they were looking for some people to work on some projects. That’s kind of how it all started, and the fact is that I picked up Paul Smith as my first client without a) having any interest in fashion at the time – I was mainly into typography – and b) not really courting any kind of work like this at all. So it was kind of fortuitous.

Kenneth Richard: So straight out of school, right to Paul Smith?

Alan Aboud: Yes. Well, effectively, it was project-based work so it was effectively setting up a company without actually planning to set up a company. It was 1989 and it was probably the first or second year into a recession, particularly in the creative industries. So up until then, at your art school graduation show, it was pretty much 100% guaranteed that you’d pick up jobs and work etc. But we unfortunately graduated during a recession. 1989 was the second year of having pretty much no internships, no work coming through, you just didn’t expect to get anything, but luckily I did. So it was a really exciting time.

Kenneth Richard: London was quite exciting – well, London’s always exciting – but London was all “Stand down Margaret” at the time right?

Alan Aboud: Exactly, that was The English Beat. And yes, today was the anniversary of the album THE SPECIALS if you knew of the Specials!

Kenneth Richard: So you were right there in the midst of The Jam, The Specials and all of that?

Alan Aboud: Yeah, obviously the height of that set up was very late 70s, so I was probably about 10 years too late in that respect, but what was happening in London at the time when I was in college was all of the rave culture, the summer of ’88, what they call the second “Summer of Love”.

There was a massive amount of elicit clubs and events that were happening, and they needed lots and lots of designers to create these flyers and these t-shirts and everything, so that was probably the most exciting part of it. Again, it was all coming from music. There was a band over here that was pretty prevalent called Soul to Soul, their first album was designed by a young designer named David James, who now runs David James Associates and his main client is Prada, so it was quite an interesting period where people were doing a lot of music stuff but ended up moving into fashion.

Kenneth Richard: Were you involved in music then, or integrating music into the stuff you were doing for Paul Smith at the time?

Alan Aboud: Well, basically, music was the main reason why I do what I do. I am from Ireland and grew up in Dublin in the late 70s and music was the lifeblood of the country. In 1979, when I was still in school, that’s when U2 started coming out of Dublin. I was so enamored by the album sleeve design and the art direction of the album sleeve design that I kind of resolved when I was about 15 or 16 that I wanted to get into this industry. Luckily, I had a really great art teacher in school who kind of pushed me to get a portfolio together etc. And I got into the main art school in Dublin called the National College of Art.

During a couple of the summers that I was there, I ended up finding the designer who created this identity for U2, Steve Averill, and ended up interning with him. So I think that’s where it all started. Steve created an official corporate identity for a band, which was unheard of at the time. He brought in photographers like Anton Corbijn to work on subsequent albums. He brought in local photographers to do these beautiful portraits and the amazing thing is – the first album that U2 did, he didn’t put them on the cover (except in America, where the cover was banned as it had a picture of a young boy with his t-shirt off). He did everything against the rules. So my biggest influence at the beginning of my career was this friend of mine, Steve, and music, basically.

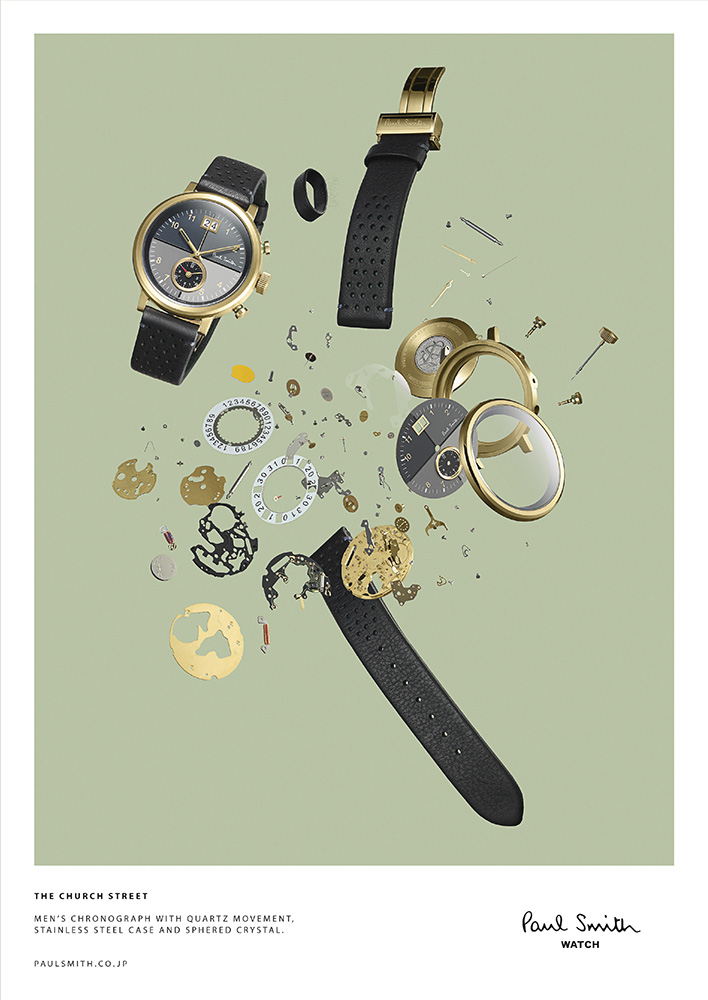

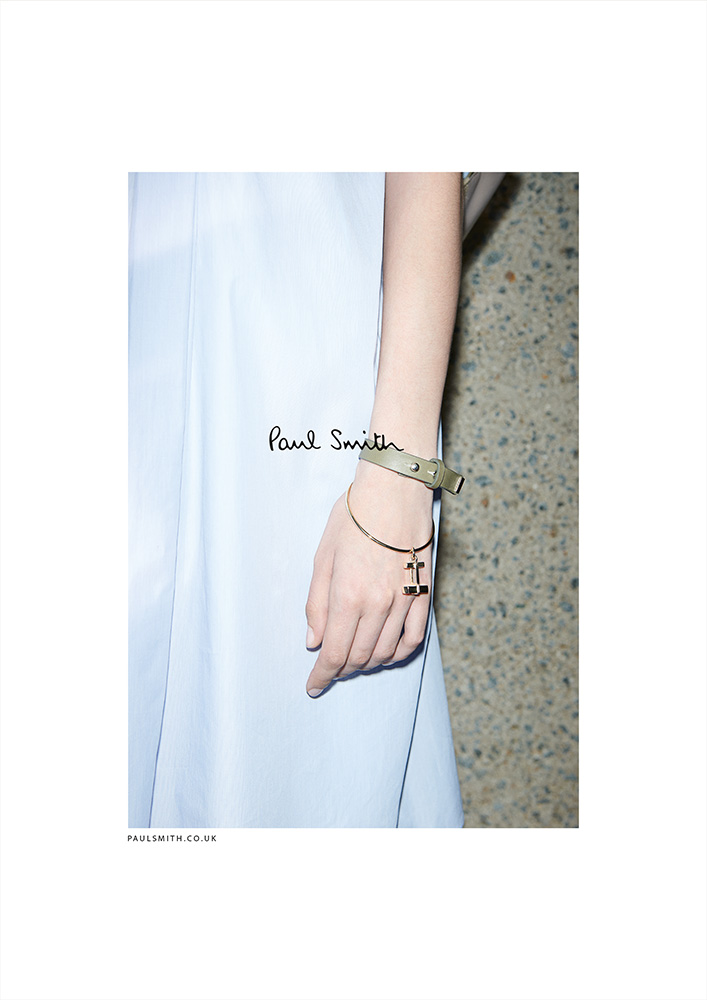

Kenneth Richard: What were the first types of projects that you did with Paul?

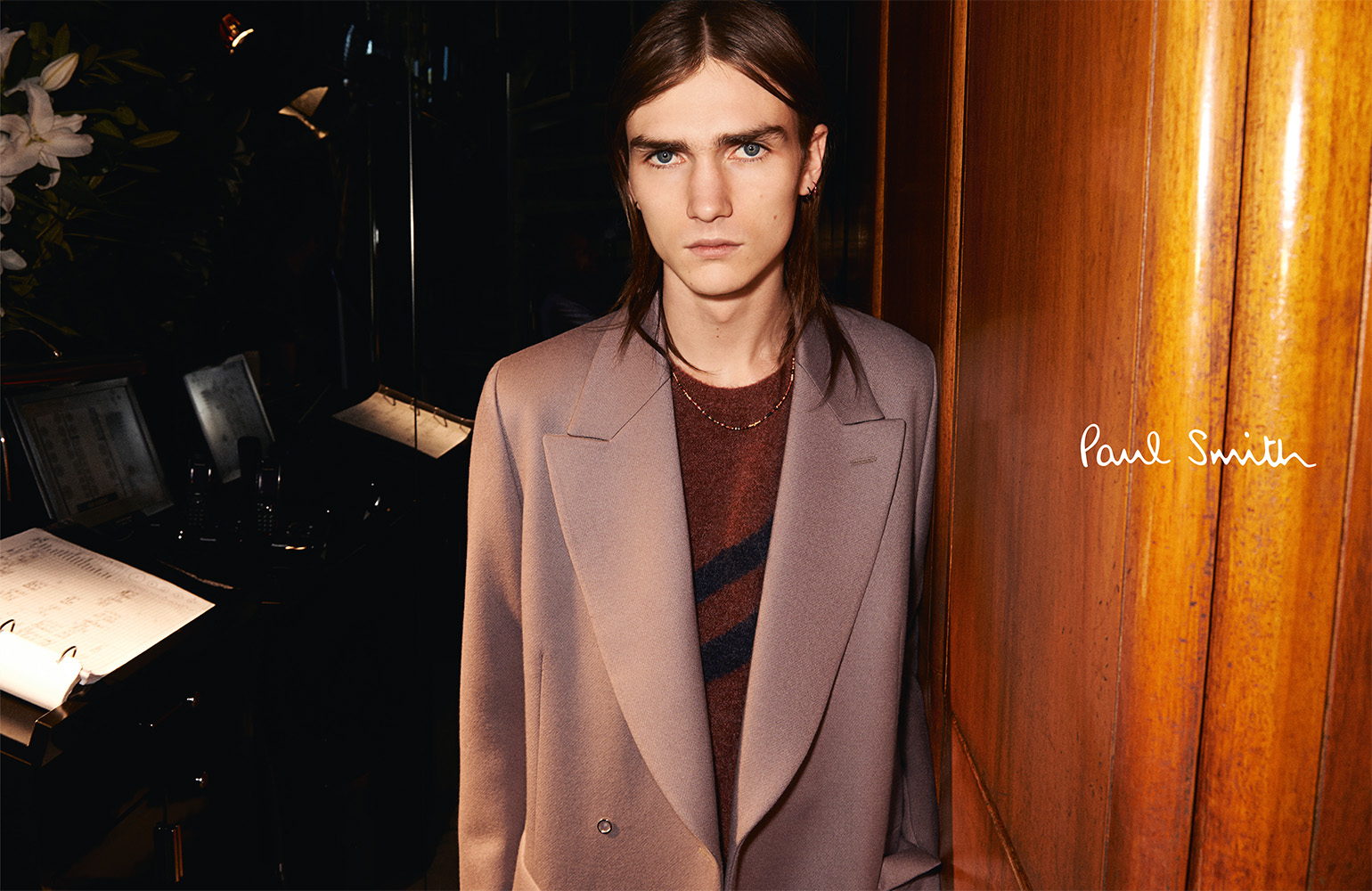

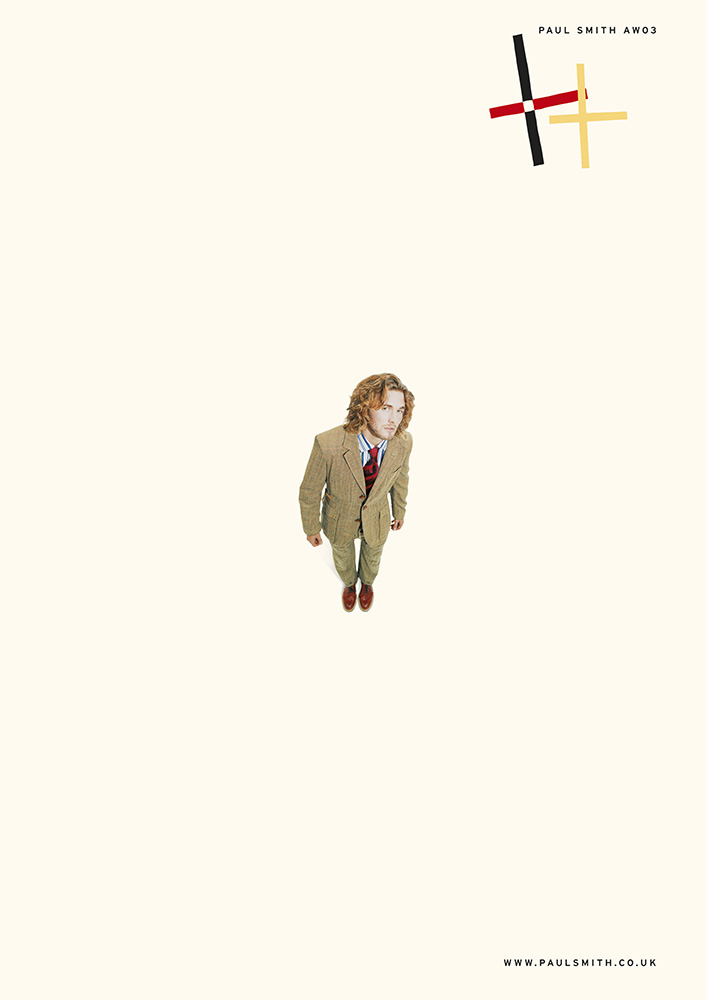

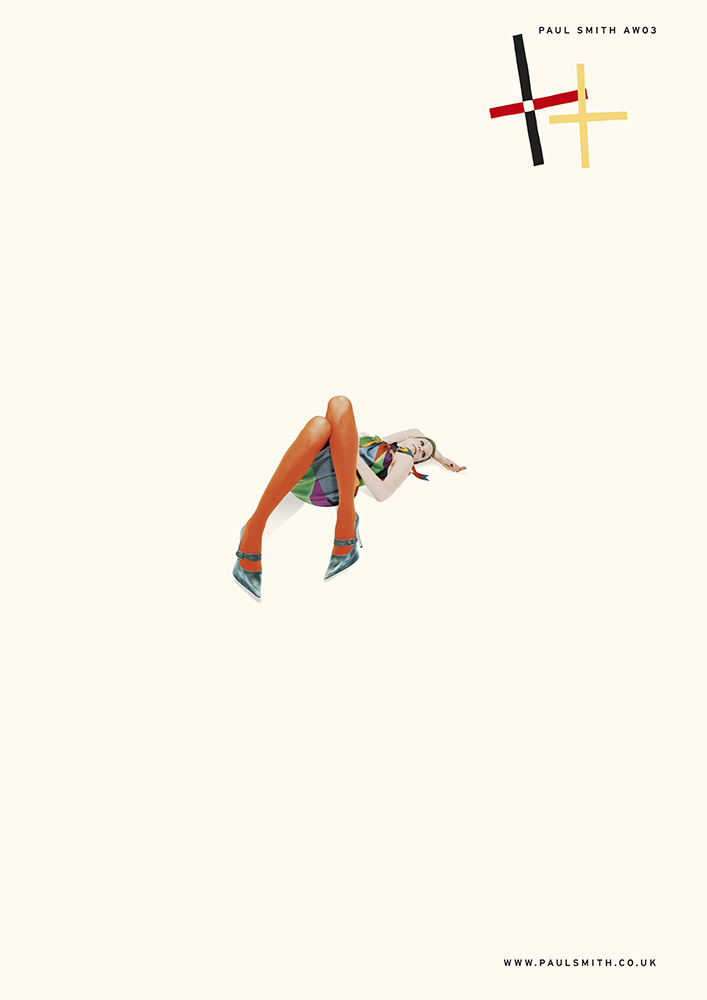

Alan Aboud: At the time, Paul Smith had the main line and he had one sub-brand which was called Paul Smith Jeans. So we were basically working solely on menswear and did everything from show invitations, sale card invitations, new season card invitations and also the advertising campaigns. At the time, there was no pressure. It was a magical time in my career and probably a lot of other people’s careers at that time because you could really do what you wanted to do. It wasn’t marketing layers; in this day and age, you’ve got multiple channels for delivery. This was simple, you had to create imagery to go in the magazines or to go on billboards etc. or to do a little brochure.

We particularly took pride in the fact that a lot of the time, we cast real people, whether they were actors or musicians or jewelry designers, and we used them in our catalogs and it was very loose and very free, it was a wonderful thing. We worked with some wonderful photographers. One particular time we really wanted to create the photography of London from the 60s and I approached David Bailey, who at the time wasn’t doing any photography, he was doing a lot of film work and video work and we managed to get him on board. It was very free, very very free. Unfortunately, the market doesn’t allow that anymore.

Kenneth Richard: Why so?

Alan Aboud: I think pressure of delivery, whether that be delivery financially or delivery of multi-channel materials. There’s too much resting on imagery nowadays, particularly for fashion brands. And I think people are scared, people are scared of failure now. The bigger the brand, the more conservative they are with the risk they’re going to take with the photographer or illustration, whatever. Like with Paul Smith in the early days, one season we did illustrations, another season we just did still lives, it was very uninhibited.

Thinking about it now with the benefit of hindsight, particularly from Paul’s perspective – he didn’t do womenswear at the time. I think womenswear is a very different thing to menswear in terms of people’s perceptions. Womenswear has a perception of being high fashion. Whereas at the time, there wasn’t really a big push for menswear – apart from Armani or Paul or Katherine Hamnett or Gaultier. I think when Paul took on womenswear in 1995, the stakes got higher and I think that probably changed things so that we needed to conform a bit more.

Kenneth Richard: How do you feel about the difference between the men’s and women’s currently?

Alan Aboud: I think men’s has definitely caught up with women’s in terms of the importance in the industry. If you look at menswear in the 80s and 90s, it was definitely the poor relation in the fashion world because I think the perception was men didn’t really need to dress differently because they wore a suit from 9 to 5 Monday to Friday. Then in the early 2000s, probably particularly with American influences and your dress down Fridays, suddenly men had to think about what casual clothes to buy. I think that’s when it started getting relevant, when people realized that men needed to buy clothes. And then promotion needed to change and advertising needed to change to show that fashion wasn’t feminine. In the late 70s or 80s, if you weren’t into punk or new wave or new romanticism and you dressed up, people would just think you were odd.

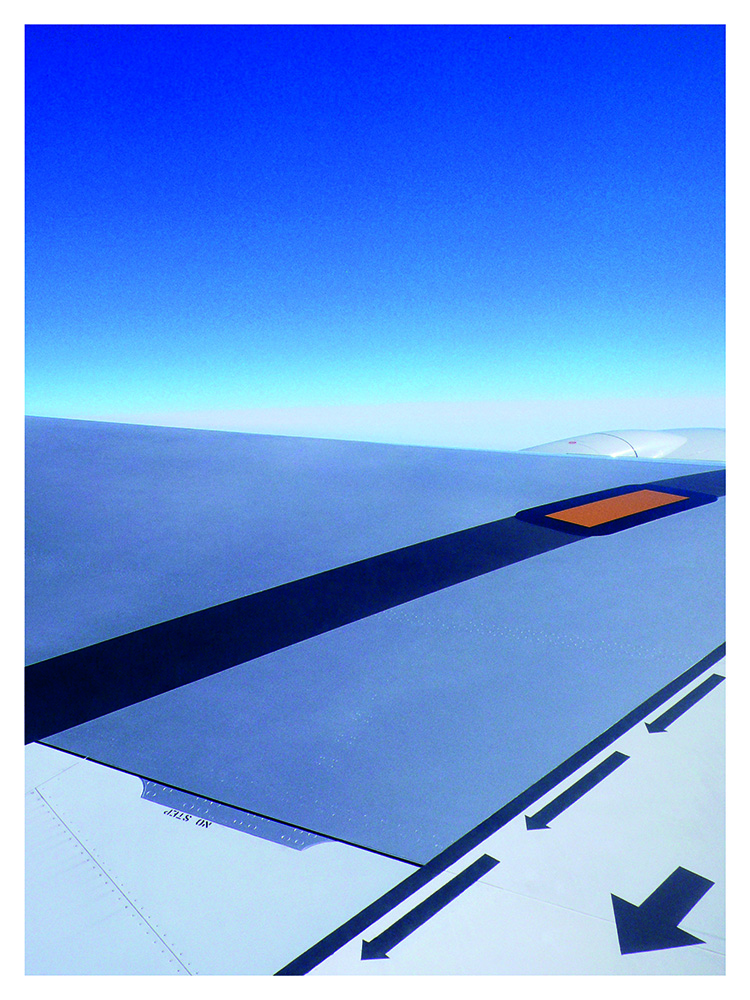

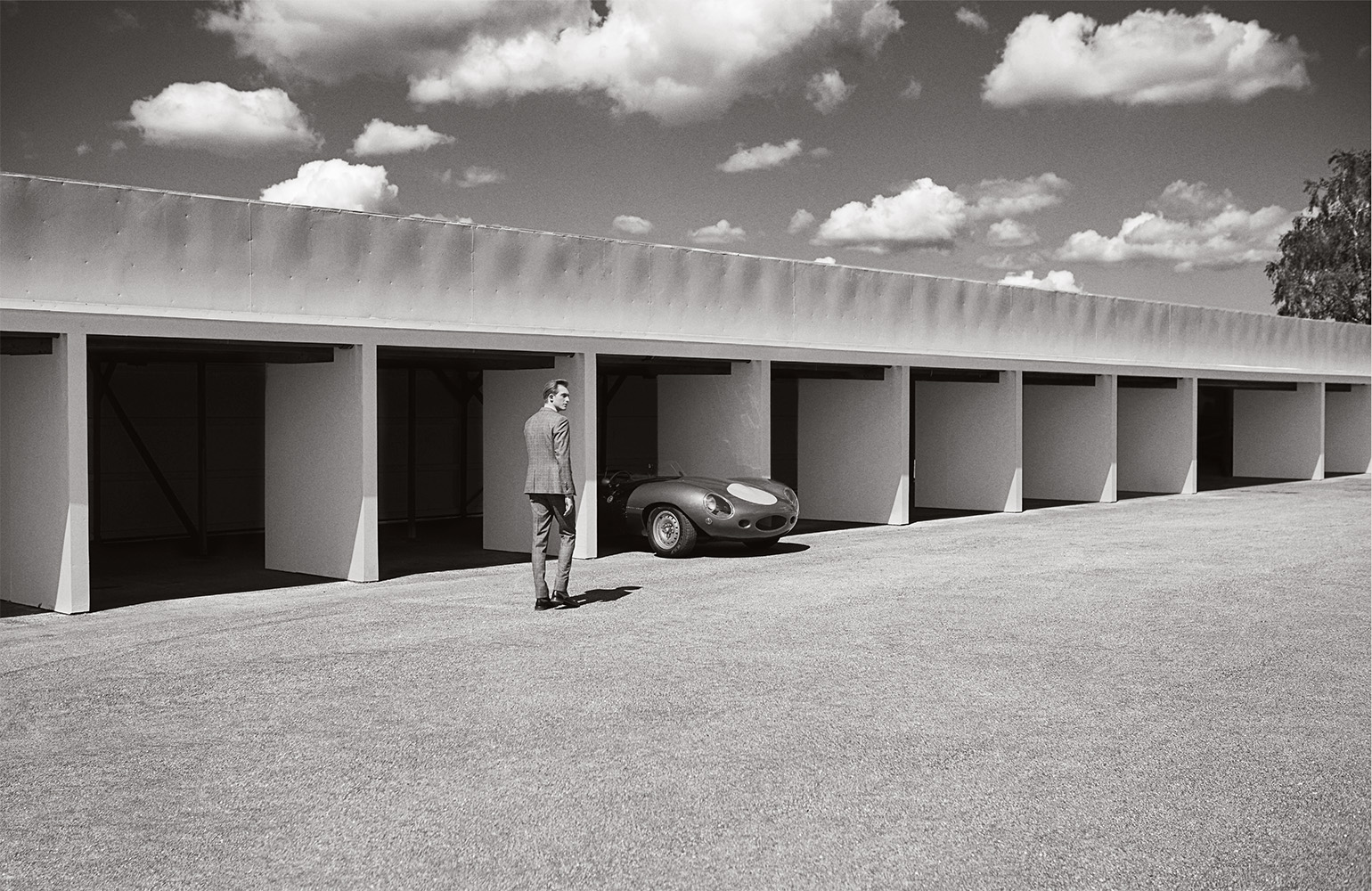

Kenneth Richard: You just wrapped up A Suit To Travel In, which is a campaign that has a print component but I think the real thinking was a video/interactive component. Can you elaborate a little bit about the changing landscape and how it relates to that program?

Alan Aboud: There are so many channels that a fashion brand needs to fulfill now with content. You’ve got Facebook, you’ve got Instagram, you’ve got Snapchat now, and you’ve got your traditional print campaigns that also need digital now so you also have films, which are an essential part of promotions. So suddenly, for the most part, in my experience, budgets aren’t increasing exponentially from clients, but the expectations are increasing exponentially. So you really have to be clever nowadays to come up with an idea that has that versatility and I think that’s what came from the film.

It was clever thinking rooted in traditional fashion advertising. It was a traditional print campaign and a traditional film, but the conundrum was how to expand that, how to get that leg to live and breathe and run for a period longer than a normal 3-month fashion campaign. That’s what made us feel so proud of what we’ve done, the fact that we’ve created these live events that have traveled around the world, public and private audiences have been party to it so they took their influences from the performances and they fed those channels for us with their own Instagram feeds, with their own FB posts. That’s what’s been quite exciting about it – that you’re actually empowering fashion followers to create their content based off of yours.

Kenneth Richard: You just described the new age of fashion communication and marketing, leveraging the strength of the networks that exist. By the way, I thought that your wonderful case study film eloquently speaks to the fact that it’s an ‘idea’.

Alan Aboud: Yeah. But don’t you find in the age that we’re in, particularly in the fashion age that we’re in, that there’s not a lot of ideas? I know that is probably contentious but –

Kenneth Richard: I don’t think of that as being relegated just to fashion.

Alan Aboud: No, no. We probably notice it because we’re in it. I agree. You look at car commercials, whatever, things like that, there’s a lack of wonderful ideas.

Kenneth Richard: Idealization is hard.

Alan Aboud: Yes.

Kenneth Richard: Plus it’s a very difficult to execute, especially in the framework of tight budgets and video.

Alan Aboud: II agree. How can you afford people like Wes Anderson to do your fragrance commercial? Only the Pradas of this world have the money to use real filmmakers.

Kenneth Richard: One of the things I really liked about what you did with regards to A Suit To Travel In is you took something and had it literally travel. And because it literally traveled, that engaged more people and expanded the reach and the network through these interactive events. All the while holding up to the standards of fashion imagery.

Alan Aboud: Well, what was really interesting about the project was it was the first time that a fashion client had come to us asking us to sell one thing, apart from our work with Levi’s.

Typically in fashion you shoot a collection, 6 to 8 images that embody that season, that collection. What was really interesting, from our point of view, was we were asked to promote one thing – the suit that didn’t crease. I think what was great about that – and the credit all goes to Paul – is the fact that for years before that, he was going on about these lovely, vintage trade magazines from the 50s and 60s from the Italian fabric mills where they had ads with slogans or captions. And he really loved the old world of advertising, the Mad Men era where you literally had a byline. And I think that was the embodiment of his concept, to say let’s just go for one thing.

Kenneth Richard: We have to talk about that iconic branding stripe you did for Paul.

Alan Aboud: I joked with a few people over the years thatI had a fear the multi-stripe pattern that we created would become my gravestone, it became that kind of a stereotype. But that came about quite a long time ago.

At the time, all of the packaging for Paul Smith was just a grey, monotone bag – which was very recognizable – with a black signature. But in 1997, we were trying to grow the identity of the brand and we thought that Paul Smith was synonymous with color – in those days – and synonymous with print. So we felt we were doing ourselves a bit of a disservice for the brand, considering the fact that your biggest advertising point outside of your magazine ads were your carrier bags. And we then set out to bring color onto the bags. At that time, Paul had produced a really simple print for some shirting for one of the collections and we came across it and we played around with the colors, thickened them up, toned down some of the lines. We presented this as an idea for a rebrand, which he really loved. And we slowly adopted it in 1998 and then probably 1999/2000, we decided to do an adaptation of that for the women’s line, which is what we called the swirl stripe as opposed to the multi-stripe.

It became very copied around the world, it was astonishing to see that stationery companies were doing diaries with the multi-stripe print, there were stores like Crate and Barrel doing multi-stripe deck chairs. The influence of that identity became so wide, way outside of the fashion world, we were totally surprised that the power of it kind of rubbed off in so many different aspects of manufacturing. But, in effect, that proved the death knell for the identity. We phased out the identity properly about 2, 3 years ago because of the imitations, because of the continuous copyright infringements, because of all the cease and desist letters that Paul Smith had to do. So effectively it went full circle, from being a tremendous success, to where in the end it became so copied that it was hard to differentiate between the real and the fake. But for that period of time, it was a wonderful identity and a wonderful way of creating product. It is quite unique, apart from people like Burberry, where you’ve created an identity and then that identity went on to product. With Paul Smith, the sales turnover with multi-stripe product was astronomical. Unfortunately, we didn’t get any royalties.

Kenneth Richard: Oh, the downside of great brand design.

Alan Aboud: Exactly. You get into it when you’re young, and when it’s between wanting to be famous or wanting to be rich, you always go for fame. But when you’re in your early 50s or late 40s, you kind of go hm… wouldn’t mind some of the riches as well… But, you live and learn.

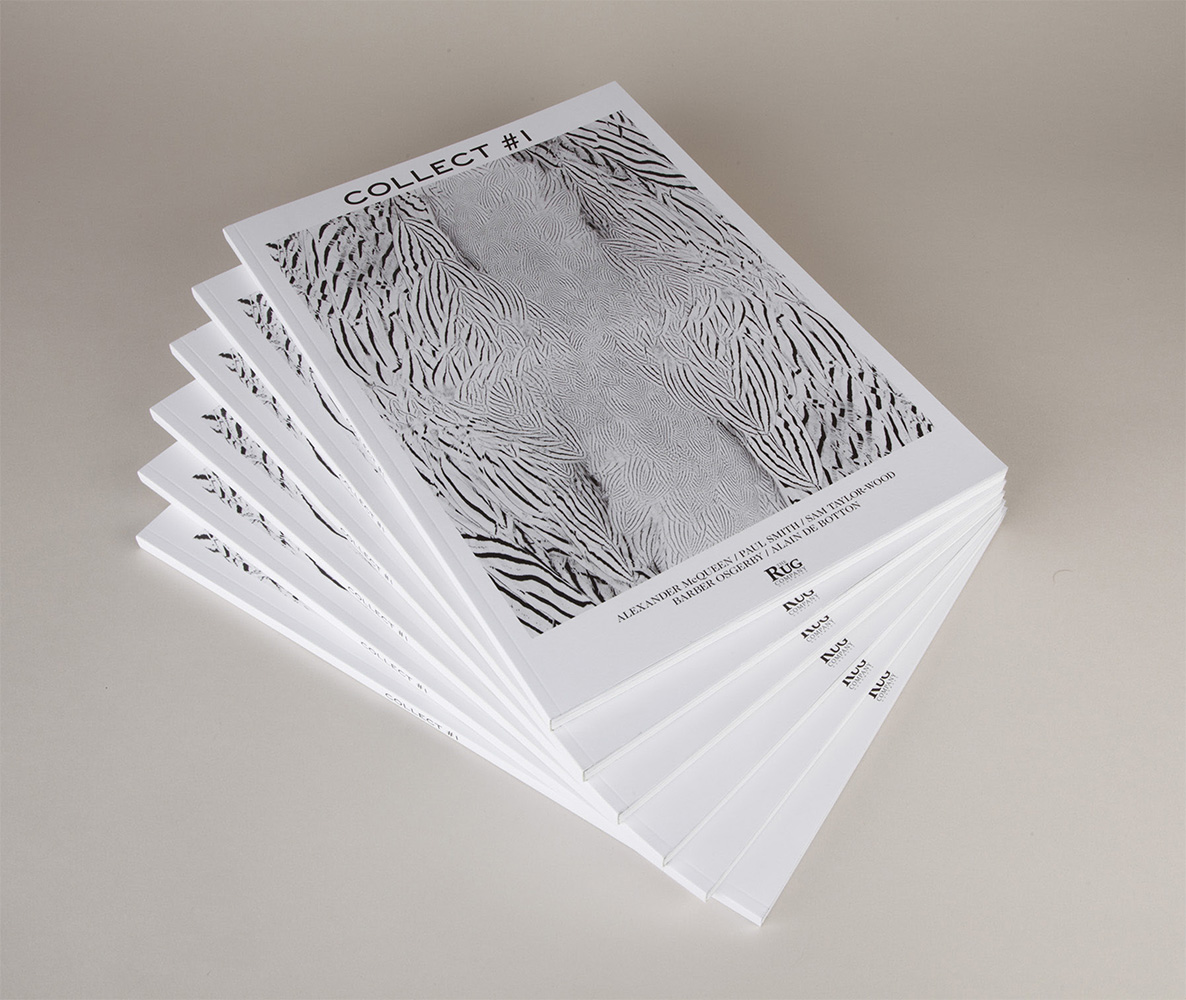

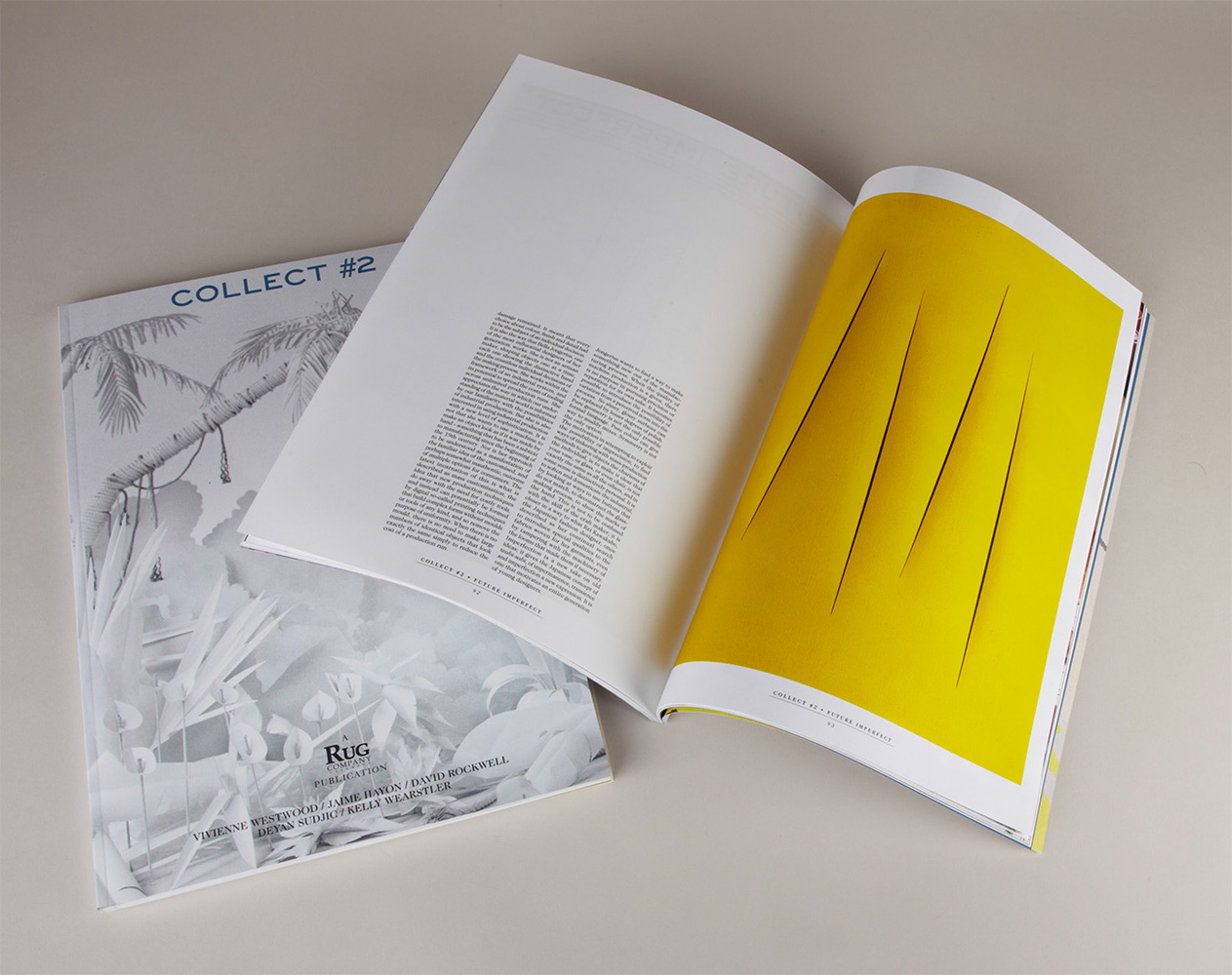

Kenneth Richard: Let’s talk a little bit about some of your other great work. You did an interesting project for The Rug Company.

Alan Aboud: We’ve known The Rug Company for a long time. It was established by a husband and wife couple, Chris and Suzanne Sharp. They produce these absolutely sumptuous catalogs every year/every two years, where they take a selection of their rugs and they shoot them in these wonderful environments around the world. It has been a very consistent, unwavering project that they’re doing, and they in turn put that into their advertising.

But they just felt it had become a bit stagnant so we had a brainstorming session with them where we said you want to still continue doing these shoots, but you probably want to give your potential customers and your existing customers something a bit more engaging, a bit more personable, as opposed to just a catalog. We pointed out to them you have lots of influences, you have lots of stories where you find your influences from, you have lots of designers who you work with, they have lots of stories about their world, why don’t we produce a quarterly magazine instead of the catalogs for a year, still do the shoots and put them into the magazine, but it just feels more like an editorial piece than a sales piece. They bought the idea and they brought in a person who had been working at the World of Interiors magazine in London as an editor. We had editorial people, we worked as creative directors on the magazine, and we helped advise on who they should interview etc.

So it was me going back to my early career because just after I started running the agency, I also worked on two design magazines, one called Blueprint Magazine in London and a graphic design magazine here called Eye Magazine. I’ve always loved magazines. And we created these really wonderful, over-sized periodicals that ran for about 9 months.

Kenneth Richard: Do you believe in editorial approach to sell product?

Alan Aboud: It depends on the product, really. If you look at fashion, obviously the whole business of fashion is based on editorial, that’s traditionally how the world went round in the fashion circles. The magazine shot your product and in return for regularly shooting your product, you’d put an ad in their magazine. So they were happy and you were happy and the customer was happy because they could see what your product looked like outside of your advertising campaign.

Nowadays it’s totally different because you’re got the Mr. Porters of the world, where you can see the product represented by someone else other than the brand. So it’s somewhat different now, fortunately and unfortunately.

Kenneth Richard: But brands are becoming editors themselves or at least publishers.

Alan Aboud: Yes. If it’s done well, I think that’s wonderful. What I find quite interesting is a lot of these publishers, they’re putting a lot of money into it, but they’re falling short on the content, the strength of the content is not consistent. I think if you’re going to get into the situation where you’re becoming a publisher, you really need to adopt a long term strategy. And I think a lot of them are just looking for short term fixes at the moment.

It’s interesting, there are people like Christie’s who now have a fully dedicated magazine, where they’re bringing in people from the fashion world to do editorials. I think this month the front cover was shot by Mario Testino.

Kenneth Richard: That makes sense as by their very nature, an auction house has stories to tell.

Alan Aboud: Absolutely. When it lends itself, that’s when it works. When you see brands appropriating content just for the sake of it, I think you can see through it quite quickly.

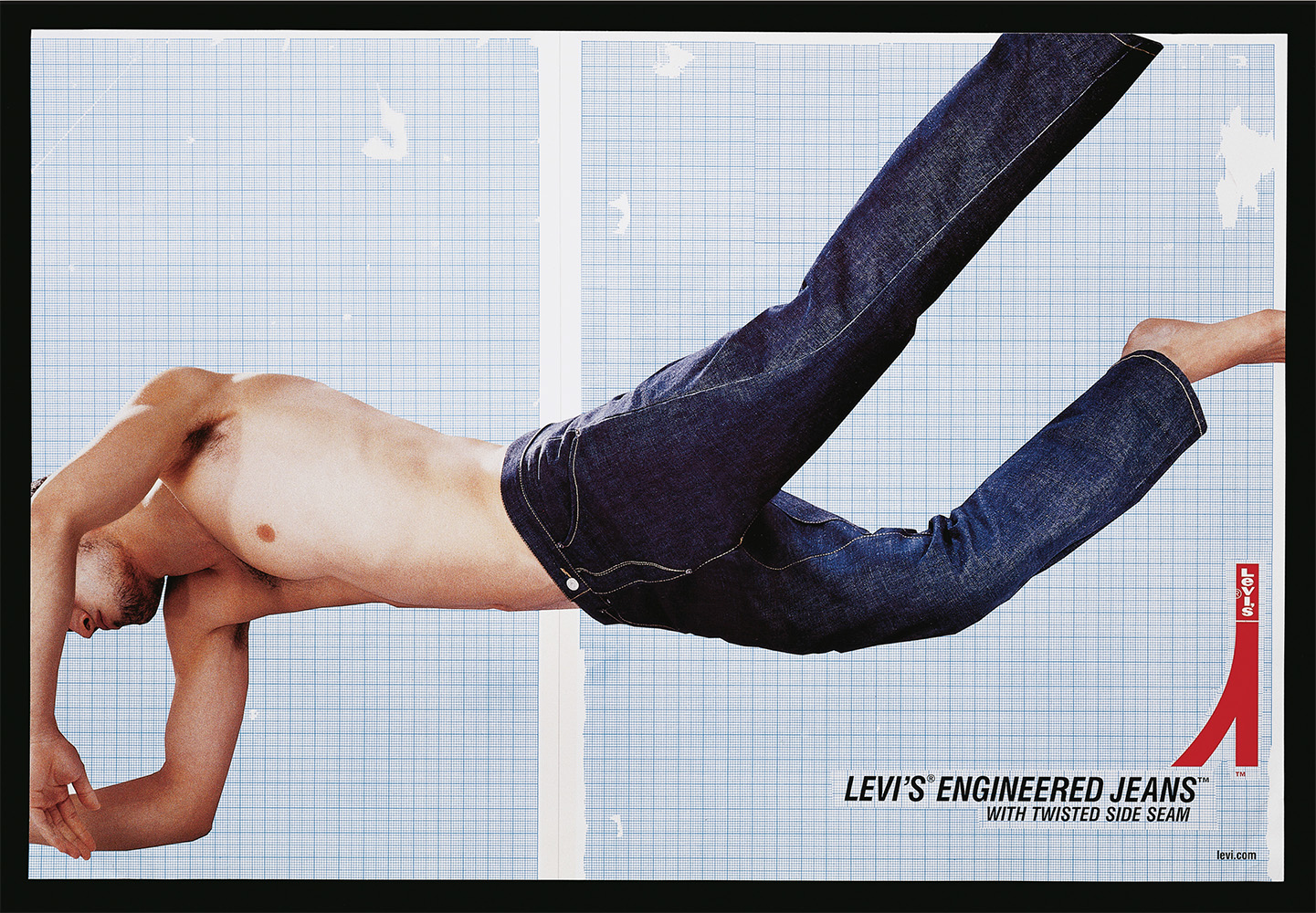

Kenneth Richard: You’ve also covered a broad gamut from men’s and women’s and accessories, but also denim and kids right?

Alan Aboud: Yes, we spent a lot of time working with Levi’s in Europe and we’ve worked with H&M over here, we’ve worked with Gap Kids in America for quite a period of time. So we’ve built quite a strong understanding, eventually and originally of menswear, because that’s where I started. But obviously through the other clients, we’ve built up a good body of womenswear work and childrenswear, which we actually really enjoy working on as well. Some people think of it as the poor relation of fashion, but we actually enjoy the creativity that it offers in terms of creating nice little films and much freer forms of advertising when you’ve got a bunch of kids in the studio.

Kenneth Richard: You mentioned earlier that you kind of serendipitously formed the agency, whether you realized it or not, because you were working on a project basis. So, how did you come to form the agency?

Alan Aboud: Well, it was very much in an ad hoc way. I was working with another graduate from St. Martin’s, a friend of mine named Sandro Sodano, who was a photographer. We basically got studio space from one of our teachers in the middle of SoHo and we decided to go for it. We didn’t have a business plan, we didn’t have an incredible ambition to have a company, but we knew we wanted to get on and do work. That was the exciting time, 1989/90 in London, everyone accepted that you’re not going to get a full time job so what you needed to do was go off and try to eke out a career by picking up different clients along the way. So it really started by the fact that we got studio space without really thinking about it and we just stuck at it and we picked up clients one by one. And it has kind of grown, not into a massive agency. We kept it really tight.

The backbone of our work has always been longevity with clients. With Paul Smith, we’ve spent nearly 26 years working together. With other brands like Levi’s, we’ve worked with them for 8 years, working on their retail advertising through BBH in London. So we’ve had these very long relationships which have given us not only a financial safety net to run an agency, but also the ability to grow in unison with clients. The whole business is about relationships, it’s like a marriage. I hate going in and working with a client on a one-off project basis because I don’t think they get the service they deserve and I don’t think I get the joy of having a project that builds. I really enjoy having a longstanding relationship with people.

Kenneth Richard: What do you feel the agency does really well that makes for those longstanding relationships?

Alan Aboud: I think there’s a lot of recognition of trust and of dependency, in terms of us being a very safe pair of hands with clients. I think when people meet me, they realize that I don’t have this kind of bipolar kind of portfolio where you’ve got crazy work and you’ve got serious work and you’ve got mad work. I think we have a very consistent design aesthetic. I don’t think we have a style to our work, but I think there is a consistent simplicity that has allowed us to work with a whole variety of brands because we’re not imparting our style onto them. So I think it is dependent on a consistency of work without breaking the bank.

Clients look at our visual credentials and know that there’s a sense of luxury in terms of the imagery. I think probably our biggest challenge – I’ve heard it a few times recently – is that people think they can’t afford us. Which is kind of a double-edged sword because while they see the work and recognize the quality of the work, they also think it’s more expensive than what it really is. So it’s kind of a compliment, but also really frustrating having to explain to people that good work doesn’t necessarily mean expensive work.

Kenneth Richard: Right. What are you looking forward to over the next couple of years?

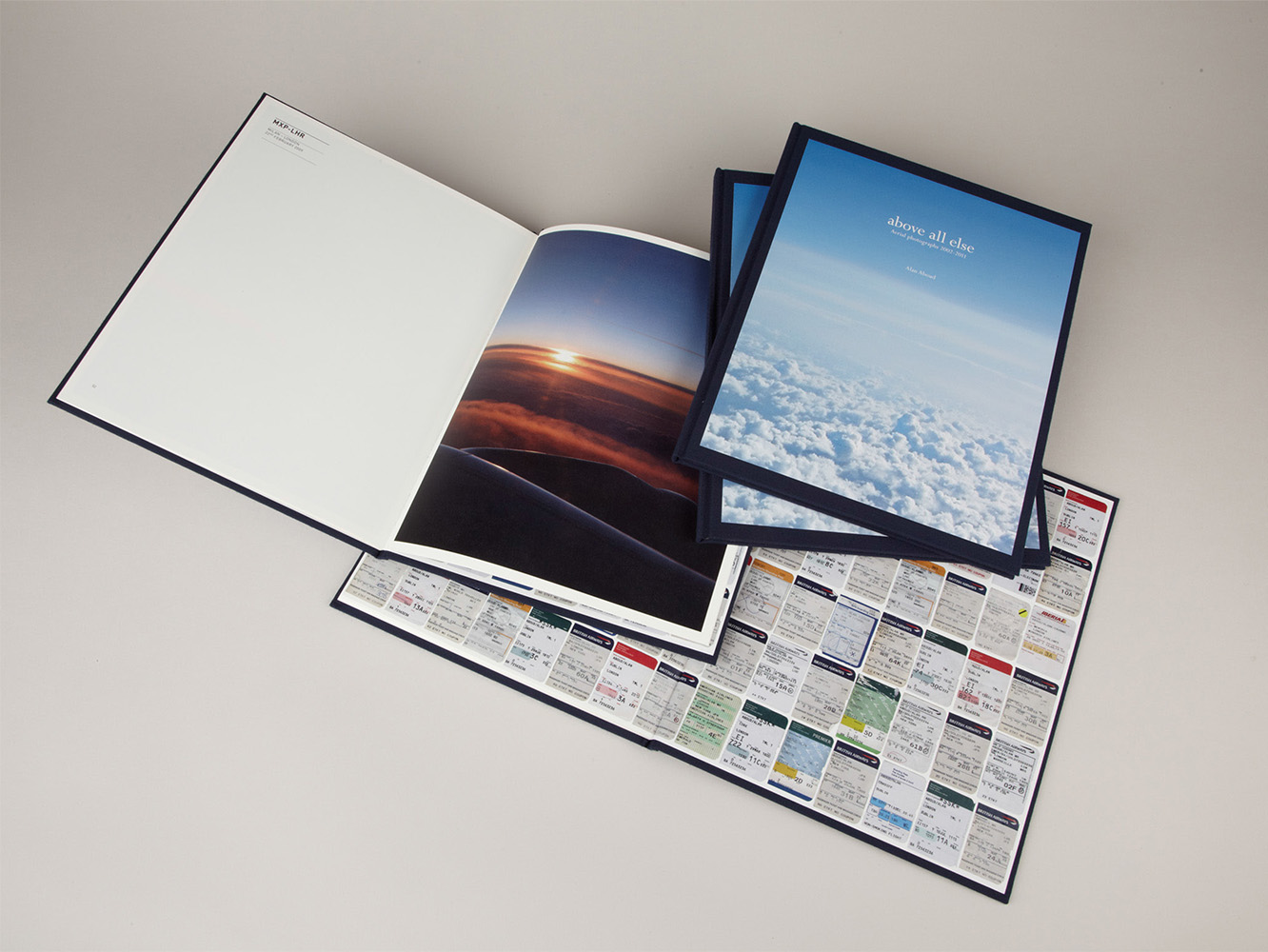

Alan Aboud: The future will still be fashion but we’re working a bit more in film as well now. I’ve been collaborating for quite a while now with the English actor Gary Oldman on some projects, and I love that type of cross-industry collaboration.

Kenneth Richard: Great actor. Anything you want to talk about?

Alan Aboud: We’ve been helping him on a project for about 4 years. He’s been working on a film documenting the life of Edward Muybridge, the English photographer. Edward Muybridge is basically credited as the father of what has become motion pictures in the way that he created movement from stills. So Gary has written a screenplay about the life of Edward Muybridge, which is incredibly interesting, involving invention, murder, arrest and acquittal. It’s an incredible story of his life. But it’s all grounded in photography so we’ve been working with Gary in visualizing the script and visualizing the whole world in order to attract potential investors and attract potential studios.

What we found in the film world is you are given one million, 10 million, 100 million pounds on the basis of a 100-page script which has no images, which has no visual identity. It has to be written in one specific program. You’re not allowed to submit film scripts in anything other than Final Draft. We always found that really weird situation whereby the most visual of media is bought and sold in black and white on photocopy paper. So we’ve been collaborating with Gary on this Edward Muybridge project and a couple of other things for him.

In some ways, we are actually bringing the fashion world in, unifying the visual world, basically. In fashion you’re working with photography, you’re working with image and you’re using image as reference, so we’re pairing up image with the written word. And that’s an area that I’m trying to work more in and get further into. I don’t have aspirations to be a film director. I don’t have the credentials to do something like that. But I do have the credentials to become a creative director in that world and to be a creative director in the way that I am a creative director in the fashion world.

Kenneth Richard: Alan, thank you very much for the time and looking forward to seeing more great ideas from the agency.

Alan Aboud: Thank you, Kenneth, and congratulations on such a wonderful resource you have created with The Impression.

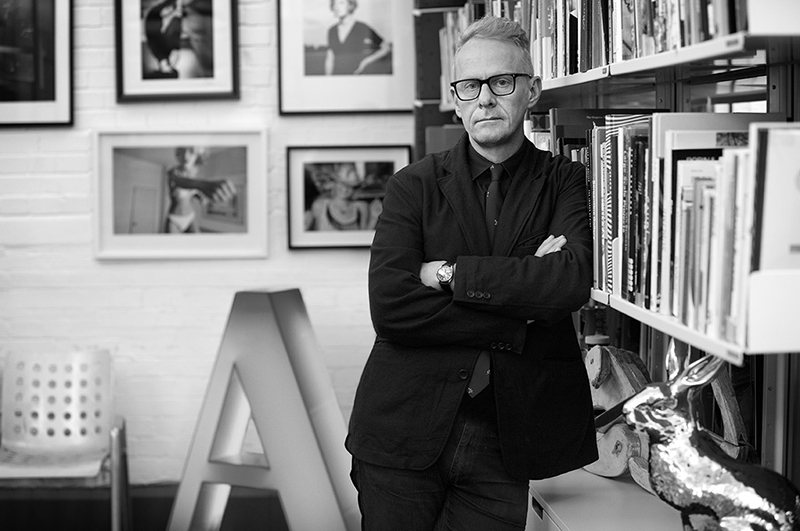

Portrait | Antony Crolla