Fashion has its fair share of icons, but few with as much originality, influence, and staying power as creative director, Fabien Baron. His pioneering work on visual identities of magazines from Harper’s Bazaar to Italian Vogue and Paris Vogue, along with his creation of iconic campaigns for clients, such as Calvin Klein, Chloé, Burberry, Bottega Veneta, Dior, Louis Vuitton, and others has helped define what it means to be a creative director today. As that role evolves in the era of digital, The Impression’s, Kenneth Richard, sat with the founder of Baron & Baron agency, photographer, and industry leader to chat about new media, the power of film, and the all-important concept.

Kenneth Richard: Fabien, nice to catch up and been watching all of your fashion film work this season. Love to dive into why they are ramping up. How many have you done this season?

Fabien Baron: Fifteen probably? But when you look at all the deliverables; the five seconds, the ten seconds, the fifteens, the 30’s, the airport version, the Instagram stories, etc., it all adds up. I think we’ve delivered more than 250 different cuts from the material we shot this season.

Kenneth Richard: Why are brands now waking up to the power of film?

Fabien Baron: Well,brands realize that people like watching videos—they’re easily digestible, and consumers like to be taken on a journey. At the same time, brands are starting to realize how malleable film is as a medium. With so many different platforms out there hungry for content, a single film can easily be cut and adapted to suit the whole range of channels. As print media is being consumed less and less, brands need a reliable outlet for image making. Film is one effective way. I think we are just at the beginning of it all.

It reminds me of what happened in the music industry in the ‘80s and ‘90s. Before, it was all about the LP—so you had the music, the album cover, and the concert as your three main elements of expression. Then came MTV and music videos. In the beginning, it was all experimental—people were just trying things, and as a result, much of it wasn’t very good. But once CD’s came in and the artwork became so much smaller, the race was on to make solid videos. The music industry began pouring money left and right into big productions to get the most impactful videos possible. Musicians had a new powerful, direct way to connect with people and tell stories that resonated throughout the culture.

I think this is exactly what’s happening with fashion and film. Of course, we are at the beginning of it—fashion brands are discovering little by little what they can do with the medium, and how they can use it to connect with their consumers differently than they do with print. I think brands will experiment more and more with film and just like it was for the music industry, they will start investing in high-level work.

That’s where it becomes more complex.

Just like good print, a good film requires talented and professional crews, as well as highly sophisticated storytelling. For fashion, that means film needs to be both visually interesting, and narratively intriguing—the ability to express the core values of a brand in a way that’s nearly subliminal.

It’s challenging to do this well. Right now, Prada is doing an excellent job of it. Miuccia has always played with film—she sees it as an extension of fashion. She was one of the first designers to use well-known film directors for her brand. She knows how to use the medium to her advantage, and she promotes her films everywhere; on her website, Instagram and other social media, even in her own theater at the Prada Foundation. You can tell she loves film and filmmaking.

Kenneth Richard: Film shouldn’t be an afterthought and when done on the cheap, reads cheap. Are brands starting to budget appropriately for it?

Fabien Baron: They’re starting to do things the right way, but there’s a learning curve. It’s often difficult for a client to understand why film can be so costly and time-consuming compared with print. Brands have had years to understand the value of good print and why a great photographer is essential. They have not made that leap with film yet; but I think for the most part, they do realize now that they can’t just give a film project to an intern as an afterthought, or just have a steady cam operator recording the looks behind the photographer during the shoot.It does not cut it anymore. So, compared to a few years back, brands are making more of an investment and seeing the difference in results.

Kenneth Richard: Which usually includes a larger budget, a team, and time.

Fabien Baron: Yes. It takes time to make a film. It takes money. It takes energy. It’s more complex than photography in many ways because it plays on different layers: the story, the editing, the music, the sound design, and on and on. It requires a lot of work and planning before, during, and after. Being a DGA director, I need to work very tightly with union crews and with my producer. Everything is timed, calculated, and scheduled to the minute. You can’t just go 5 minutes over. The consequences are too expensive.

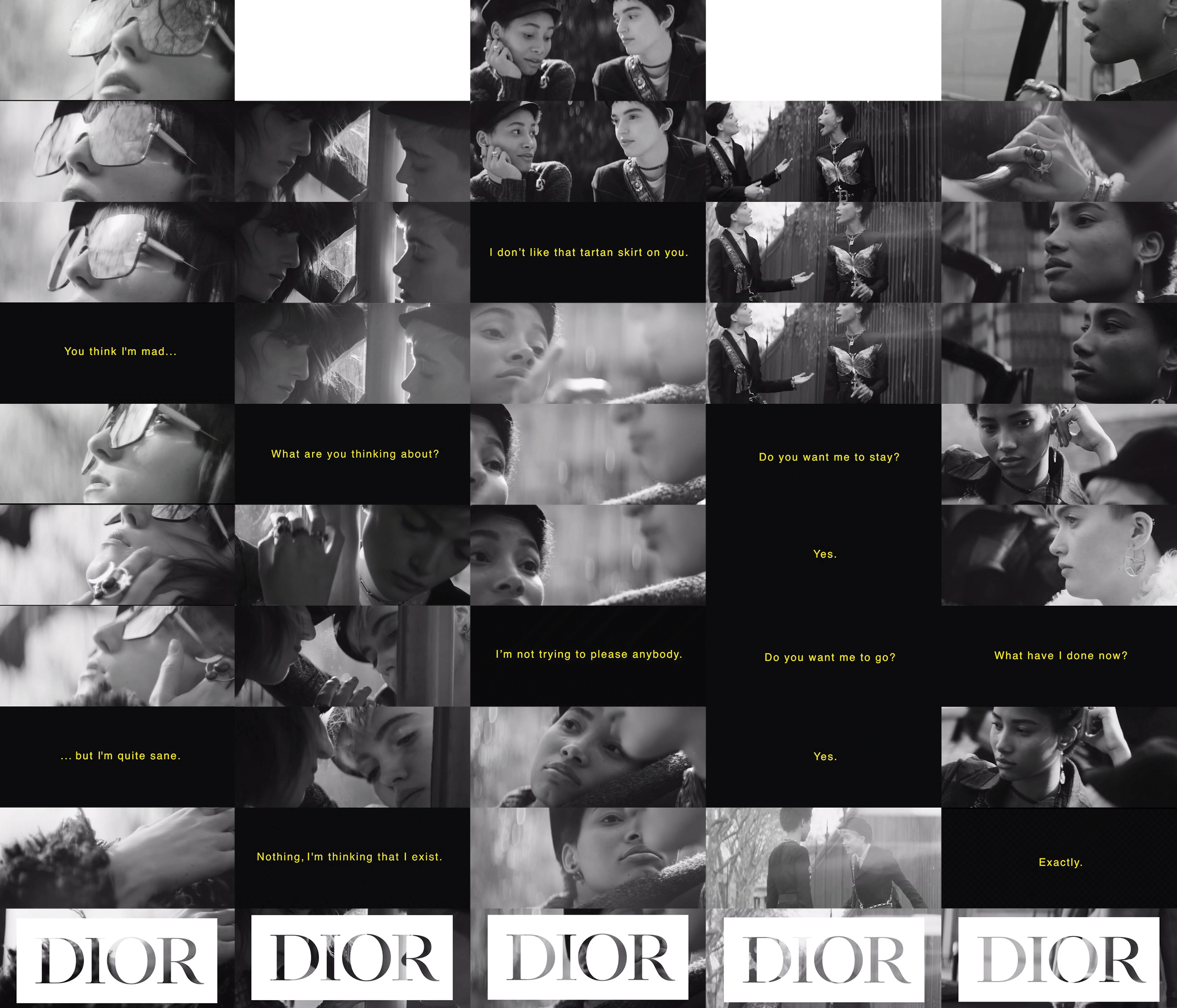

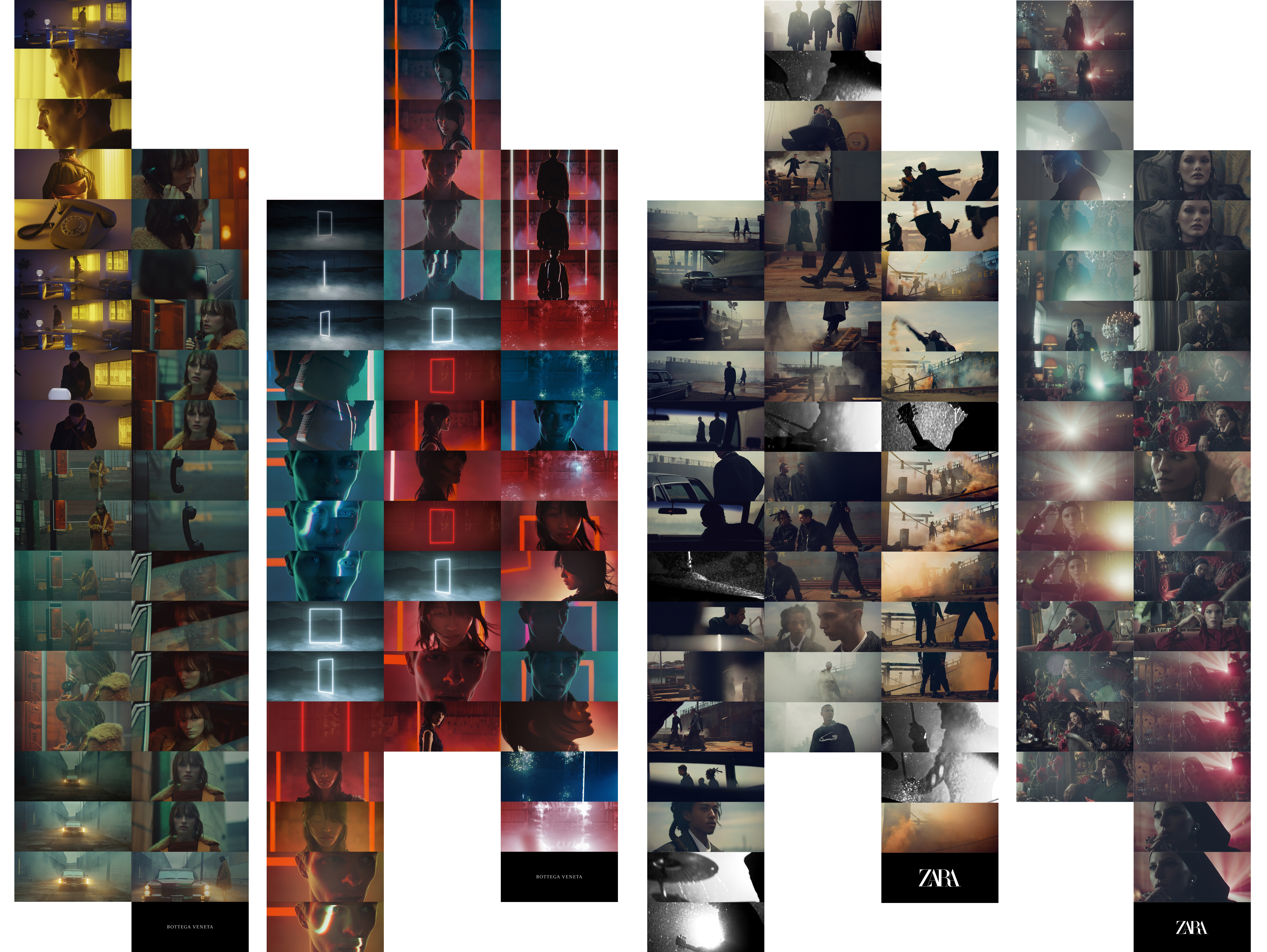

In regards to the concepting process, I always develop a picture component, a film component, and a digital component. These things need to complement one another, but tell their own unique story that’s appropriate for the medium. So often, the photography looks one way, the film another, and social media another. For instance, for Zara—Steven Meisel shot the stills, and his pictures were precise and posed, laying or sitting down in the environment. The next day when we shot the film, I had the models very much in motion, with very different, dynamic lighting. The two pieces were unique unto themselves, but both instantly recognizable as Zara.

Kenneth Richard: And narrative?

Fabien Baron: Well, conceptually, I always try to build around a storytelling element in my films—otherwise it’s just fashion recording. Which is fine too, but certainly it does not communicate the core of a brand. I mean, the point of film is narrative, right? So, you need to have a story, even if it’s subtle, and without dialogue. The same principal is applied to the digital campaign.

When it comes to storytelling, the outfit changes are the real challenge for fashion films. It can put strange restrictions around the narrative. Why would a person come in a room wearing one outfit, and then turn the corner and be wearing another? So, you need to really make sense of the clothes, in a way that’s authentic to the story.

When we see a fashion spread in a magazine, you might see a woman standing by the door in a long dress, and the next page she’s sitting on a sofa wearing another—it’s all fine. The reader can accept a print series with 10 different outfits in 10 different situations. With film, you can’t get away with that. There needs to be logic to it, and a thread the viewer can follow.

Kenneth Richard: What can brands do to help promote their films?

Fabien Baron: Brands need to use it intelligently and maximize their assets. When we do a film we probably get around six hours of footage—that’s a lot of material that can be used in so many different ways. With good planning, it’s very easy to reuse, retouch, redo, and tailor that footage to provide fresh expressions across all your different channels. Brands need to understand that and leverage it more.

Kenneth Richard: Let’s talk Instagram and film.

Fabien Baron: Well, I know that Instagram is trying to push the vertical format. They believe that vertical is the natural way to shoot on a phone—which is basically true. But by stressing vertical, they are also trying to force the film industry and the fashion industry to mimic the street look. And ultimately, it’s not a very artistic way of presenting fashion because you can’t focus on more than one thing. So yes, you can capture the fashion, but the narrative is gone, the dream factor is gone. There is a fundamental reason why film was invented in a horizontal format. It’s necessary for context, situation, narration, dialogue, and story-telling.

I believe it’s important that film remains in a horizontal ratio. It’s fine to be vertical when doing something casual—but when a brand invests $500,000 to $700,000 for a film, using professional film people, I don’t see how you can say, “Listen, let’s just shoot this vertically or we will crop into it.” The film industry is laughing about that—they’ve sharpened their tools for over 200 years, they know what works.

And stepping back to look at it from a bird’s eye view, brands need an image— and that image needs to be even more impactful and iconic than ever. They don’t need cutesy, little back and forth animated images on Instagram stories only. That’s their salt and pepper. Many of these brands have spent years building their image—they need to continue strengthening that image to remain on top.

I would love to see the new Instagram TV provide an option for posting horizontal formats and make it easy for people to expand it when they turn their phone. In the meantime, we are just going to turn our films to keep the width intact, rather than let them get cropped. People will simply turn their phones. Wow! How lazy do we all need to become?

Kenneth Richard: While on the subject of twist, what’s your take on the changing landscape of media?

Fabien Baron: I’ve always been someone that encouraged clients and partners to use different types of media. I pushed Calvin Klein into going more outdoors—at that time, it was just TV and Broadway shows like Cats who were buying buses. And I remember saying to Calvin, “Imagine if we put something attractive on those. People would notice, it would stand out like crazy.” I pushed for billboards for Calvin too—they weren’t used then so much for fashion. I think I was one of the first to use wild-postings for fashion.

I was always into doing things differently. Like with packaging, I thought why don’t we do a sleeve over the fragrance packaging, with one of the key images from the campaign? People recall the ads that they see in print or on television—this way when they come to the store they’ll recognize the product. So, I’ve always looked for, “new media,” if you will.

Today, there are so many different platforms, and so many different layers of messaging. In a way, it’s a playground. I think the most important thing in this landscape is the concept—it needs to flex and adapt to all these layers, keeping its integrity while being expressed differently. So, when you look at print, you express one aspect of your concept. The film delivers another aspect. You don’t get the same exact thing—that would be totally redundant. The concept has to be multifaceted. You can’t say, “Okay, we’re going to do everything kind of the same to be consistent.” That’s not enough anymore. You need to use the power of the medium to reach people on different levels─ on an aesthetic level, on a cultural level, on an emotional level—all these different ways of triggering something with the customer. It’s extremely important.

Basically, you want a global concept that works in different ways to express a global idea that springs from what the brand is about. So, if you look at the entire campaign package, the conversation is about the brand—but within each element, the conversation can go into specifics. In print, I may be trying to promote a key product and an idea. In the film, I’m delivering the emotion. On Instagram I’m pushing the voice, bringing the brand’s personality to life. It’s a little bit like being a person. You use your hands to gesture, your voice to talk, and your style to express your personality. But you’re just one person. That’s the way I look at media.

What is interesting is when the concept really works—suddenly it becomes very easy to implement that idea across the different platforms, and each plays off the other to bring it back to the core message. You have to take a big picture view, and let everything work together as a world. And ultimately that world always brings you back to the source—the brand, and to what their story is all about.