Unveiling the Timeless Tapestry of Japanese Fashion: Where Innovation Meets Tradition, and Designers Weave Their Unique Threads

By Neal Bhattacharya

Over a thousand years ago, in ancient Kyoto, a lady of the court named Sei Shōnagon penned some of the world’s earliest fashion critique. With a subtle eye for fabric, pattern, and seasonality, Shōnagon appraised items of clothing worn by the court members who populated the inner palace. She recorded in her diary the delight she found in the cooling effect of “trousers in the lapis lazuli blue of summer insects,” but dismissed, in another entry, the pretentiousness of an official’s red cloak. (Red, she claimed, was far above the official’s station.)

Shōnagon’s sophisticated takes on court dress were an early manifestation of Japan’s refined fashion sensibility, one that continues to shape present attitudes and practices. Today, the fashion industry is worth nearly $89 billion and is only continuing to expand. Highly influential Japanese designers, such as Rei Kawakubo and Issey Miyake, transformed the global fashion landscape by drawing on the island’s psychic and visual traditions. In this Insight, we’ll trace the development of prominent ideas that have surfaced throughout Japan’s history, from the refined court wear of ancient Kyoto to the shelves of Uniqlo.

The findings in this Insight can also help decipher the nation’s more outré subcultures. To an outsider, Tokyo’s street fashion seems impenetrable and hypermodern—its brash fits only the products of individual personalities. But the intricacy behind those fits becomes approachable by keeping in mind principles that have informed both Sei Shōnagon’s critique and Issey Miyake’s designs, principles that we’ll highlight.

Index

The Essence of Cloth

With wave-like pleats that reshape the body, Issey Miyake’s clothing design has had a transformative impact in both Japan and the West since the ‘70s. But his work is not only a reflection of personal genius. He has been strongly influenced by the most iconic piece of Japanese clothing, its national costume in fact—the kimono. The kimono, literally meaning “a thing to wear,” was once commonplace, but it is now mostly worn on special occasions such as New Year’s Day.

The kimono’s origins date back to Sei Shōnagon’s time, the Heian period, when Japan developed an identity of its own after sealing itself off from Chinese influence. Composed of eight pieces of draped cloth, the underlying structure of the garment appears simple, but this simplicity allows for a wide range of expression for one’s personality in the choice of pattern or small alterations of form.

It was by means of the kimono that Miyake was able to break free of fashion’s center of gravity, Paris, and chart his own path. Whereas Parisian fashion emphasized refinement through glamor, Miyake found in the kimono a refinement that arises only from subtlety. According to fashion historian Bonnie English, the designer saw the very “essence of cloth” in the drape, flow, and layering of the kimono—all of which embody the core function of a garment: the framing and elision of the body. This influence is most evident in Miyake’s line Pleats Please, where the distance between the cloth and body is highlighted in dresses and gowns that seem to float and ripple above the wearer.

Lolita fashion, a subculture of street wear, builds on this tradition by accentuating the space between dress and body. In shops dedicated to Lolita wear in the Harajuku district of Tokyo, bright stockings and caricatures of Victorian dresses abound. Although the doll-like garments seem as far as possible from the traditional form of the kimono, one can still detect in the dresses a characteristic attention to drape and flow that derives from historical costume.

Another aspect of the traditional fashion design is kasane, or color layering. Layering is a way to achieve harmony between apparently disparate elements, or to highlight one element through the multiplication of it. To evince fine taste, women traditionally wore seasonally appropriate colors at the hem, neckline and cuffs of their kimonos. Today, Junichi Abe, the designer behind Kolor, utilizes kasane to great effect. Abe proves that loud colors don’t have to clash, nor do hybrid fibers. In Kolor’s latest S/S collection, synthetic fabrics and plastic sit on top of and cohere with organic fibers. No single element stands out—all melt into a balanced vision. The vitality of Tokyo streetwear owes something to this tradition of layering, too, as it often juxtaposes colors, fabric types, and even different subcultures.

Like Tea

A key element of Japanese fashion that Miyake popularized is its emphasis on simplicity, another divergence from Western mores. But we should draw attention to the fact that simplicity is, of course, not the same thing as simpleness. Simplicity in this sense is a conscious suppression of the ego, a harmony with and appreciation of nature. The idea is perhaps best embodied in the Japanese tea ceremony, where ascetic ritual codes heighten the participant’s perception, allowing them to meditate on delicate flavors and austere artwork. It is a simplicity arrived at through the utmost exertion, by pouring one’s energy into focusing on the present.

Rei Kawakubo of Comme des Garçons, draws on this principle of simplicity, and her influence can be seen in a host of Western designers, including Marc Jacobs and Miuccia Prada. Although CDG’s designs are nowadays often richly colorful, its early dresses, trousers, and skirts were largely monochromatic. Kawakubo championed austere, gender-neutral clothing—an ethos which is paralleled in street fashion’s gender-bending and gothic fits. As an “anti-fashion” visionary, Kawakubo worked to throw out almost every normative attitude of the couture world—she once described her designs as Zen puzzles—and this manifested in an approach to fashion that valued the subdued and monastic. An appreciation of raw and organic material, which arose from such minimalism, is a through-line that can be traced from CDG’s inception to the present.

An appreciation for natural material is also the driving force behind Visvim, a brand founded by Hiroki Nakamura. Apart from employing minimal processing and traditional techniques in its manufacture, the brand features “dissertations” that highlight how these techniques inform the thinking of Visvim’s designers. In one dissertation, a writer charts the decline of the traditional chirimen fabric (once used for kimonos) and its recent revival by contemporary designers. Visvim also exemplifies another trend of Japanese fashion, Americana, particularly in its dedication to raw denim. Here the brand can accentuate its commitment to natural processing while harnessing a wry fascination with American culture.

Uniqlo’s Dominance

So far, we’ve elaborated on trends in Japanese fashion primarily by examining the nation’s historical trends, avant-garde designers, and street fashion. But can these principles be found in clothes made for a larger market as well? The success of Uniqlo gives a resounding yes. Uniqlo (pronounced YOO-neh-kloh) is valued at $9.6 billion and is now one of the top 10 fashion companies worldwide. The retailer is dominating the market at home (its parent company is the largest by value) and Uniqlo is slowly expanding into flush markets in North America and Europe, all while accelerating growth in Asia.

Uniqlo is able to achieve this success while hewing close to Japanese principles of fashion design and sensibility. Nobuo Domae, then CEO of the company, now at MUJI, gave a speech at the Japan Society where he credited the success of the retailer to its embodying a national character. He notes in particular a concern with timeliness, a trait that Sei Shōnagon claimed was a mark of good taste over a thousand years ago.

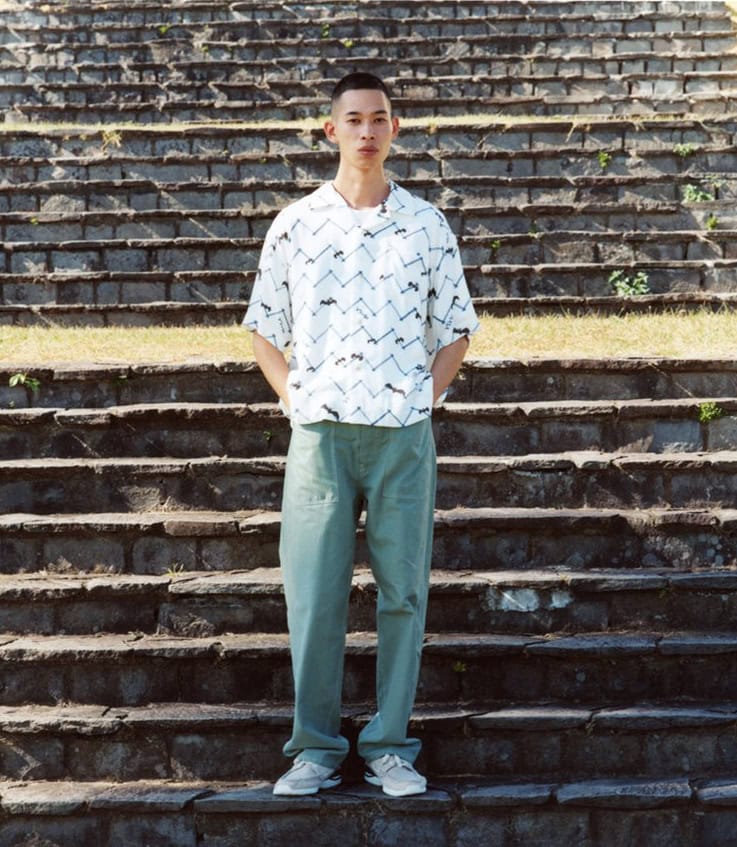

Like some of the designers we touched on, Uniqlo’s clothes are known for their minimalism, and the retailer sells basics that are, well, not basic because they are marked by silhouettes that signal timeliness, but without being brash, much in the vein of CDG. By scaling up minimalism, Uniqlo can appeal to the fashion conscious while filling the market void for layerable basics left by retailers like Gap. Here, then, is a modern form of kasane.

And as the Business of Fashion notes, Uniqlo has been able to appeal to younger demographics, too. Its nylon bag—part fanny pack, part Prada handbag—went viral, garnering over 80m views on Instagram. Uniqlo’s forward-looking attitude gives reason to think the retailer will go far. Visiting its US flagship store in New York, I felt like I was browsing for socks and tees on a spaceship.

Key Takeaways

Japanese fashion has continued to innovate throughout its millennia long history, while a sense of continuity that embeds novel forms in a series of psychic and visual patterns. We look forward to seeing how designers and street fashion continue to build on characteristic trends and infuse them with their distinct personalities.