At Mak Vienna, A Helmut Lang Exhibition Reframes How Fashion Builds Meaning

By Kenneth Richard

If you walk into MAK’s Helmut Lang exhibition expecting mannequins and nostalgia, you’re going to be pleasantly disoriented. There isn’t much clothing. And the exhibition is better for it.

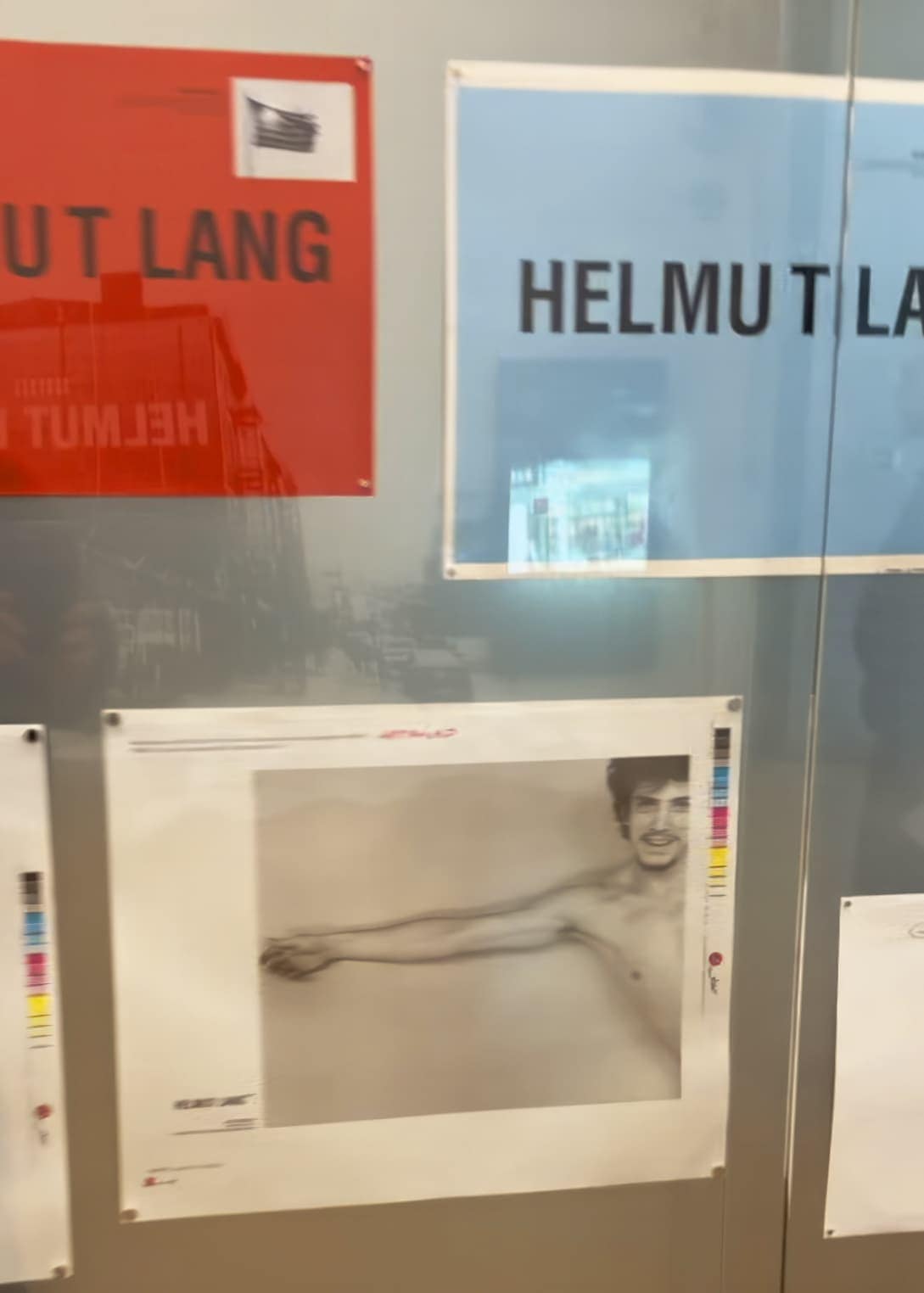

MAK Helmut Lang Archive, LNI 649. Photo: MAK/Christian Mendez

What MAK has done with Helmut Lang Séance de Travail 1986–2005 is something rarer—and, frankly, more useful for anyone who actually builds brands for a living. This show doesn’t flatter fashion with a greatest-hits parade. It dissects the operating system. It treats the label as an idea made tangible through space, typography, process, and a kind of calm, unbothered authority that most luxury brands now chase with twice the noise and half the conviction.

“Simply showing Helmut Lang garments on dressed mannequins would not be the appropriate approach,” MAK Curator Lara Steinhäuber told me during a walk-through. The museum’s advantage is that it can show the evidence behind the myth, because it holds what Steinhäuber calls “a kind of corporate archive reflecting the history of the label between 1986 and 2005.”

HELMUT LANG. SÉANCE DE TRAVAIL 1986–2005 / Excerpts from the MAK Helmut Lang Archive

MAK Exhibition Hall

© kunst-dokumentation.com/MAK

The scale is staggering, but the point isn’t. In 2011, after a fire damaged Lang’s own archive in New York, he donated “a very huge conglomerate of over 10,000 objects” to MAK. Not just clothes—mostly the material most brands lose, discard, or never bother to preserve: lookbooks, advertising layouts, proofs, tear sheets, Polaroids, passes, internal documents. The unglamorous architecture of a label becoming a label.

MAK Helmut Lang Archive, LNI 572-2-3. Courtesy of hl-art.

“We have been working on the archive, digitalising everything throughout the last 14 years,” Steinhäuber said. The show had been discussed before, but “it wasn’t the right moment.” Eventually, MAK’s Director Lilli Hollein “was able to convince him (Helmut himself) to do the show, and that it was the right moment.”

MAK Helmut Lang Archive, LNI 566-9-5-1. Courtesy of hl-art.

That “right moment” matters. Fashion exhibitions have become their own genre now—blockbusters that audiences approach with a single expectation: the mannequin. MAK understands that expectation and deliberately refuses it. Lang, of all designers, rewards that refusal. His genius wasn’t only the cut of a jacket. It was the totality of thought around how fashion is experienced: how you enter it, how you read it, how you remember it, how it communicates when it decides not to communicate.

Steinhäuber kept returning to one word that, in 2026, feels like a provocation: space. “One of the main topics that we have… is space, then we have the topic of identity… communication… backstage… and another very important topic for him, artist collaborations.”

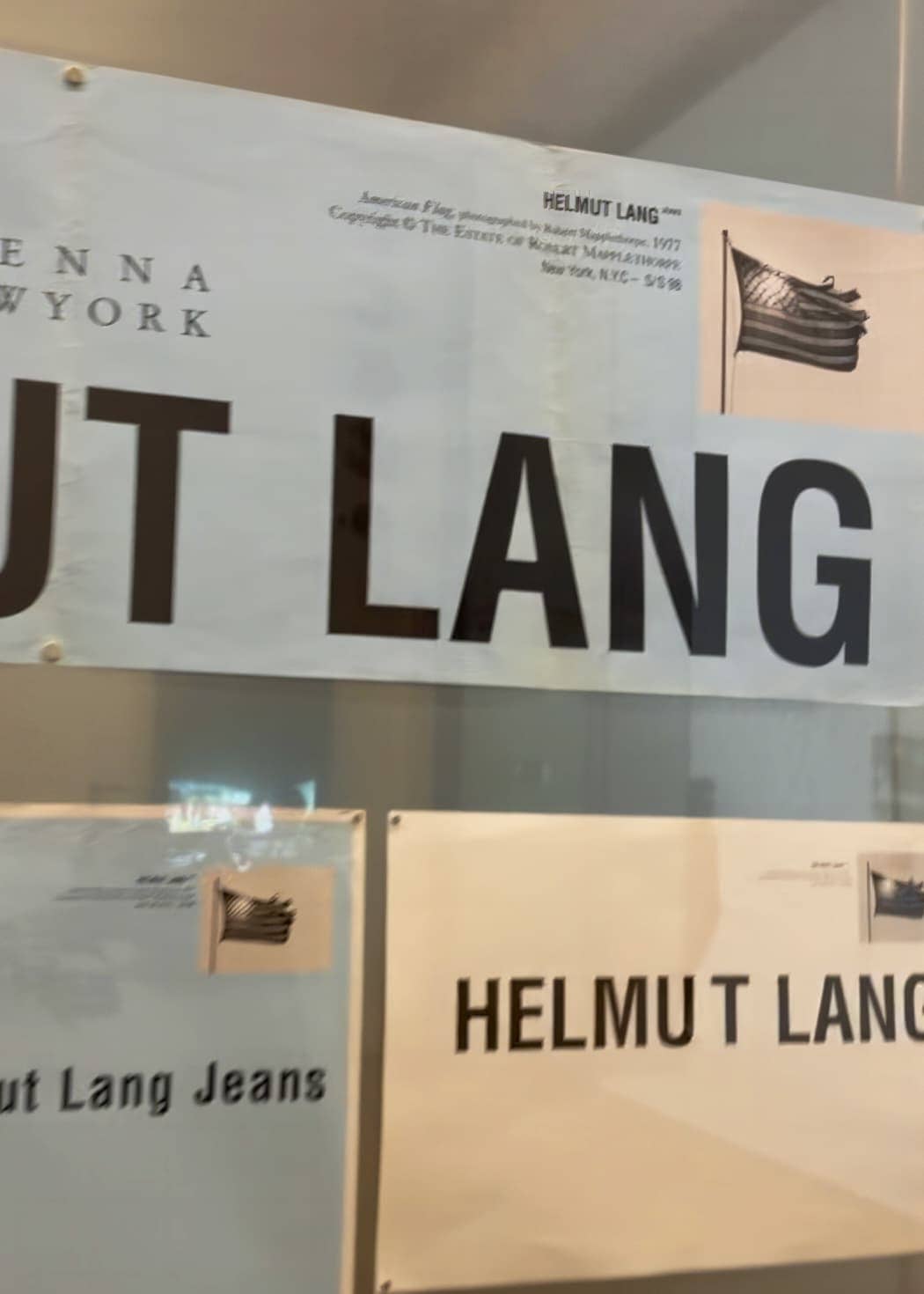

Space, in Lang’s world, is not minimalism as a look. It’s luxury as an instruction. MAK makes this literal by echoing the architecture of the Greene Street store, where “you would have these black boxes in a very white space, museum like area when you would enter the shop.” Steinhäuber called it “a very intellectualised way of consuming fashion,” and she’s right: Lang didn’t retail product, he staged meaning. Even the people who weren’t buying came to look. “So many people… told us that it was really like something people would even go to just to see the art,” she said, describing windows that featured Louise Bourgeois, and an environment that functioned like “a curator, curatorial, or like museum mask space that he constructed with his shops.”

MAK Helmut Lang Archive. Courtesy of hl-art.

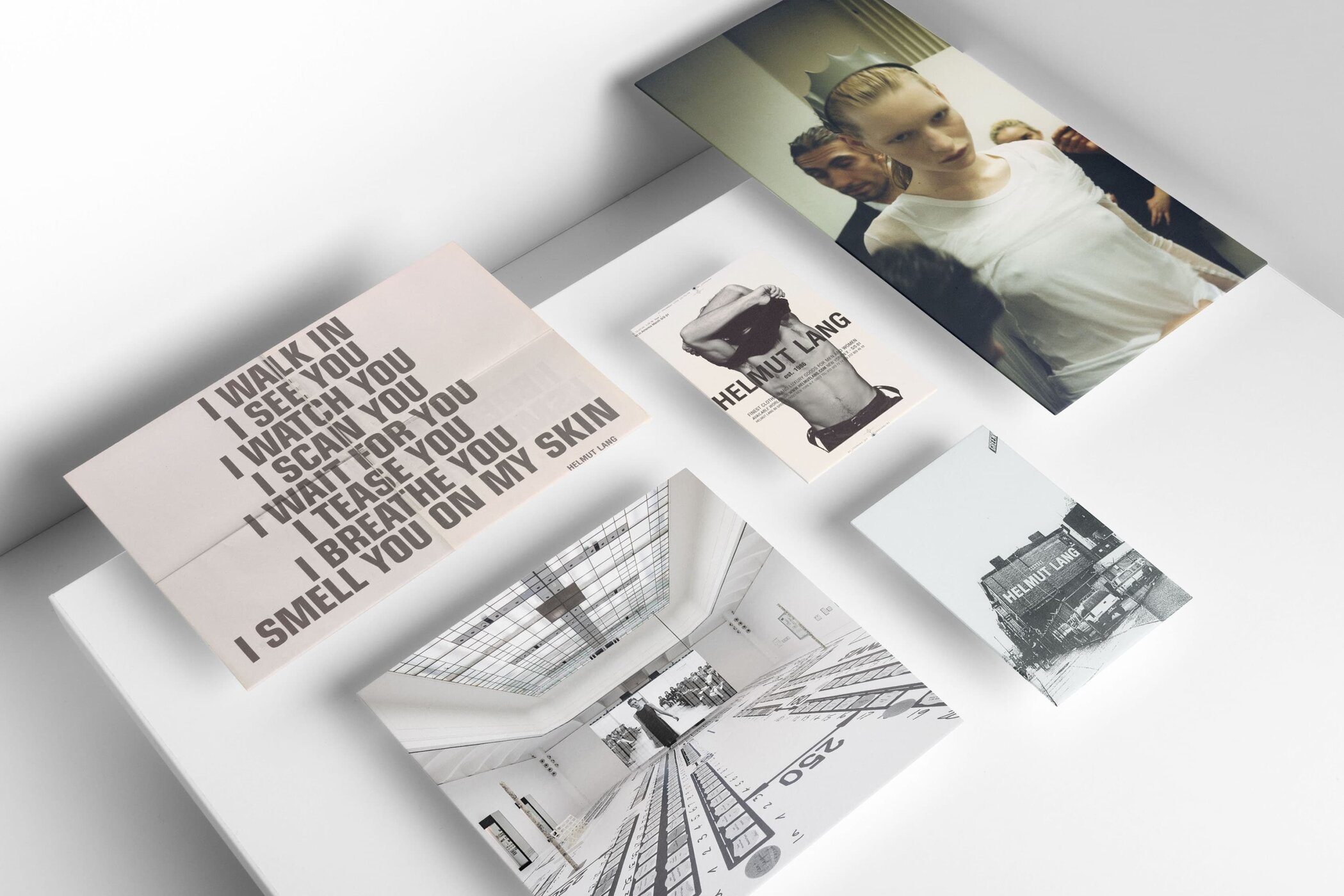

And then there’s the brand identity—the clean typography, the strictness of the logo, the white space that reads like confidence rather than absence. Steinhäuber made an unexpectedly sharp connection: “It’s a kind of lineage that you can trace back to the 1920s when you’re looking at Coco Chanel,” she said, pointing to the way Chanel used “blank space and like clean typography,” a logic that continues “until today… brands like Balenciaga, that somehow worked with a similar appeal.”

The difference is what Lang did with it: he made restraint feel like a stance. In a market that keeps shouting “heritage” and “craft” and “community” over glossy video, Lang’s white space reads like a threat: you don’t need to explain yourself when you’ve built a world that speaks.

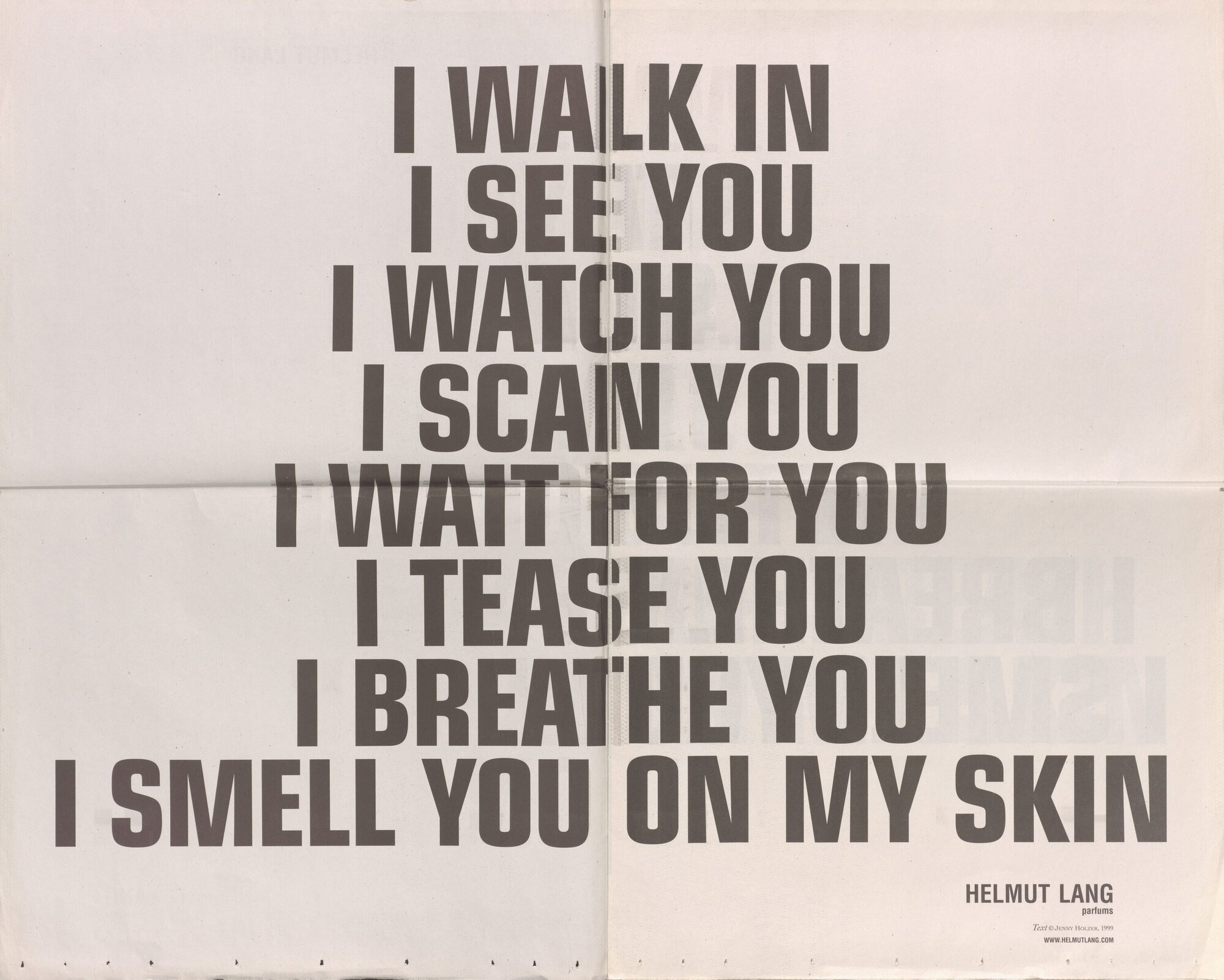

That’s where MAK’s most intelligent curatorial decision lands: it treats the brand’s communication as the main event. The advertising isn’t a supporting character; it’s the thesis. The show tracks how campaigns were built because, in this archive, you can literally see it. “You can trace back the company’s history,” Steinhäuber said, “and you can see like how the process of developing these campaigns was realised.”

What hits hardest is Lang’s use of artists not as decorative garnish, but as identity. He didn’t just collaborate. He aligned. He used artists the way other brands use ambassadors—except his ambassadors were ideas. Steinhäuber described Lang’s strategy as something close to appropriation: “He appropriated the Mapplethorpe… into his own imaginary of the advertisements.” A tiny image—Bourgeois, Mapplethorpe—floating in an ocean of white with the logo doing the heavy lifting. “You would only probably be able to read [it] if you were really… an art connoisseur. Or willing to even look and engage,” she said.

HELMUT LANG. SÉANCE DE TRAVAIL 1986–2005 / Excerpts from the MAK Helmut Lang Archive

MAK Helmut Lang Archive. Courtesy of hl-art.

That’s the point. The work didn’t beg for attention. It rewarded attention. Which is, quietly, the most luxurious behavior possible.

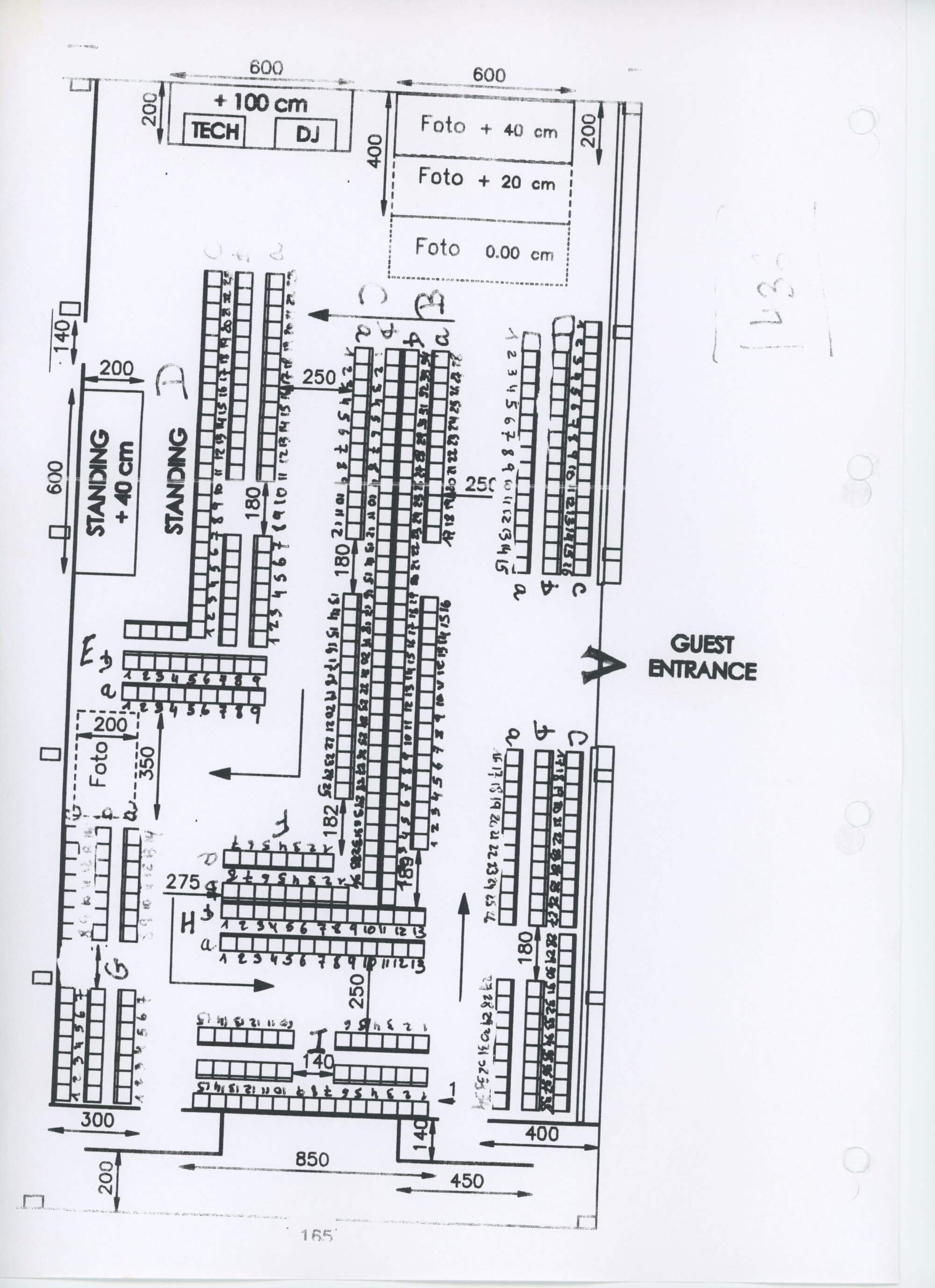

If the retail space is Lang’s theater, MAK’s centerpiece is his backstage brain. The exhibition’s Séance de Travail section turns process into spectacle with one move that feels almost indecently brilliant: a blown-up seating plan printed onto the floor. You stand on it like you’re standing inside the machinery of power—front row as literal architecture. “What you can see here is on the ground. Seating chart,” Steinhäuber said. “We were… fact checking with him… and what [the curator] decided… was to have this floor plan here.”

HELMUT LANG. SÉANCE DE TRAVAIL 1986–2005 / Excerpts from the MAK Helmut Lang Archive

MAK Exhibition Hall

© kunst-dokumentation.com/MAK

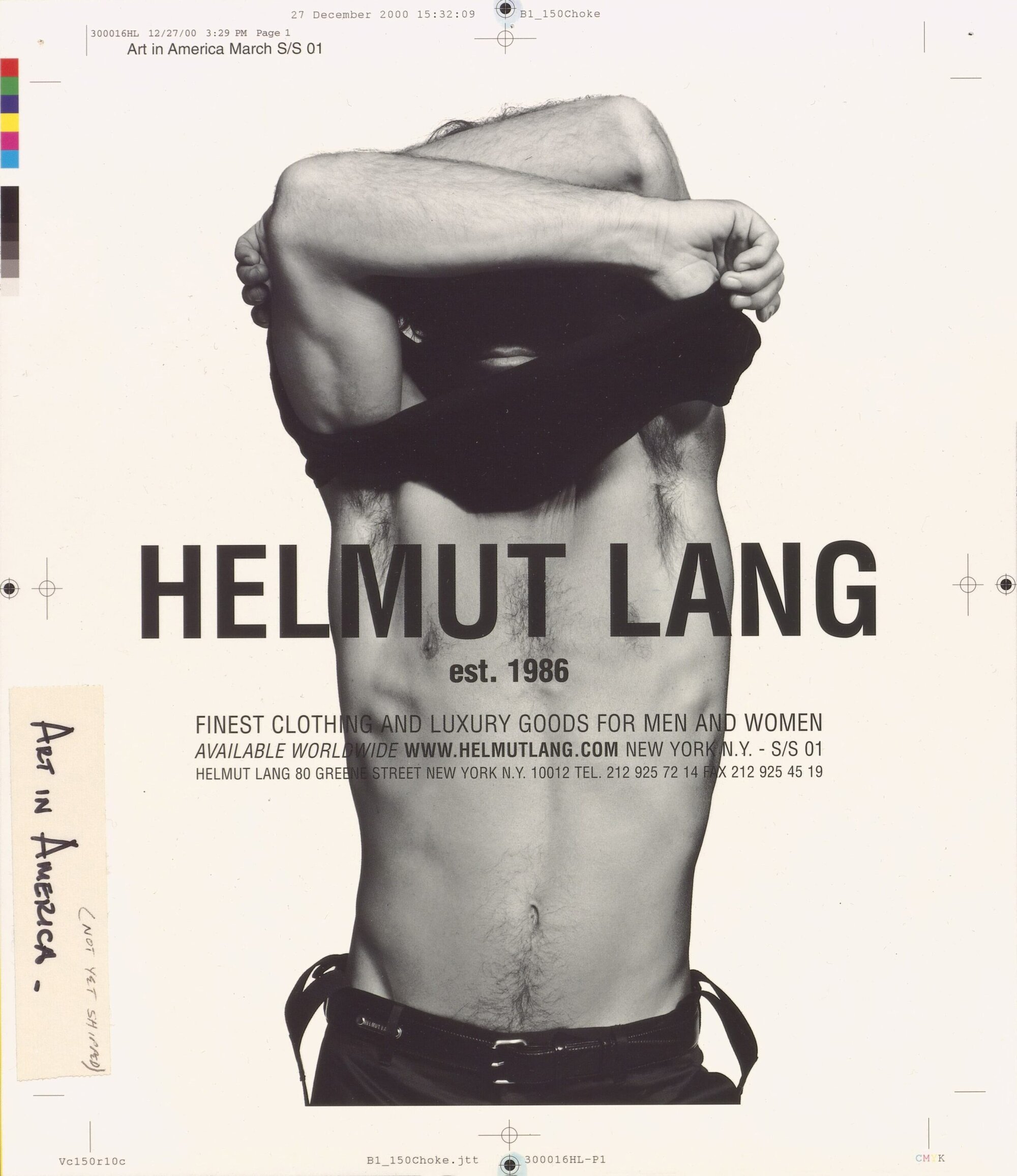

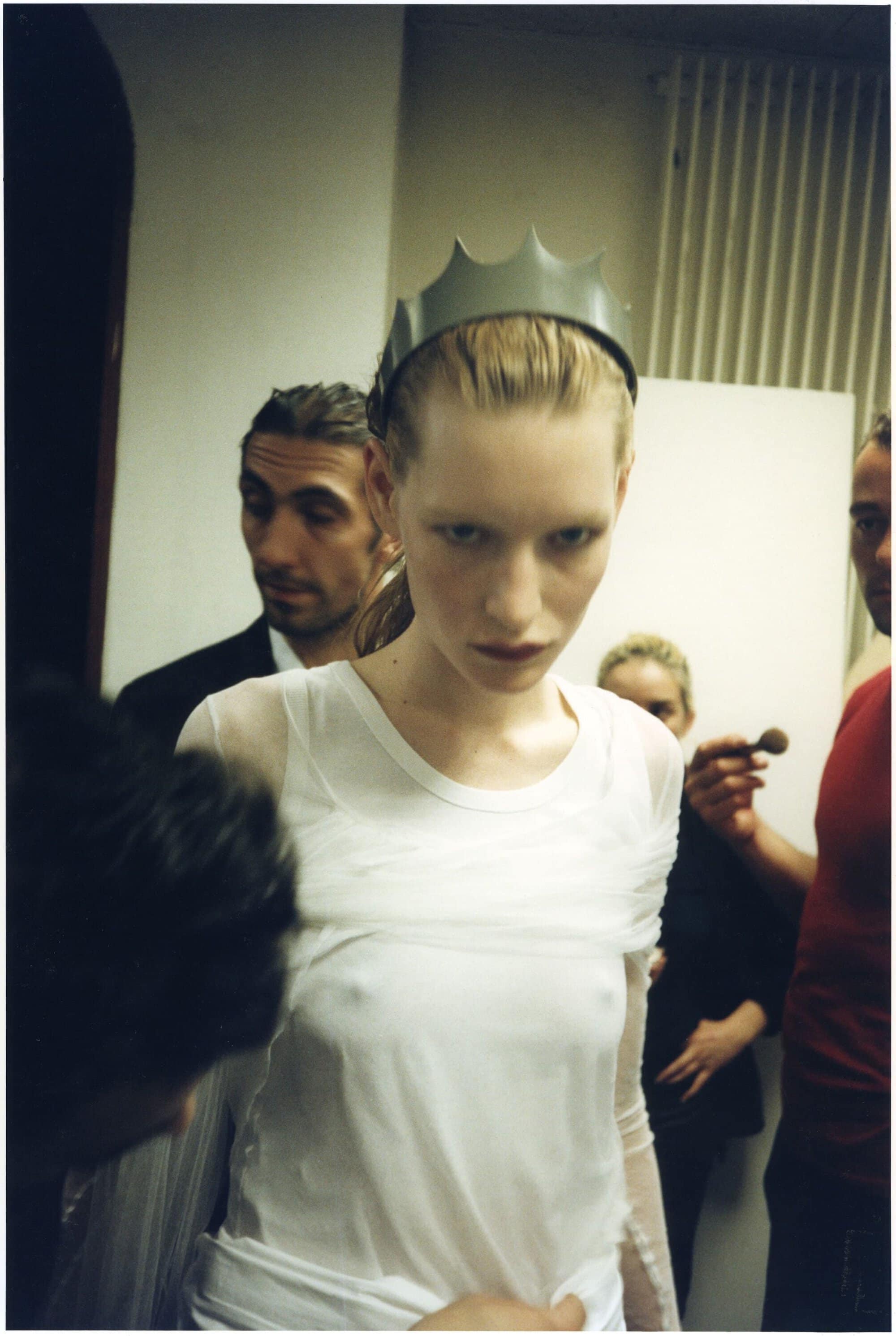

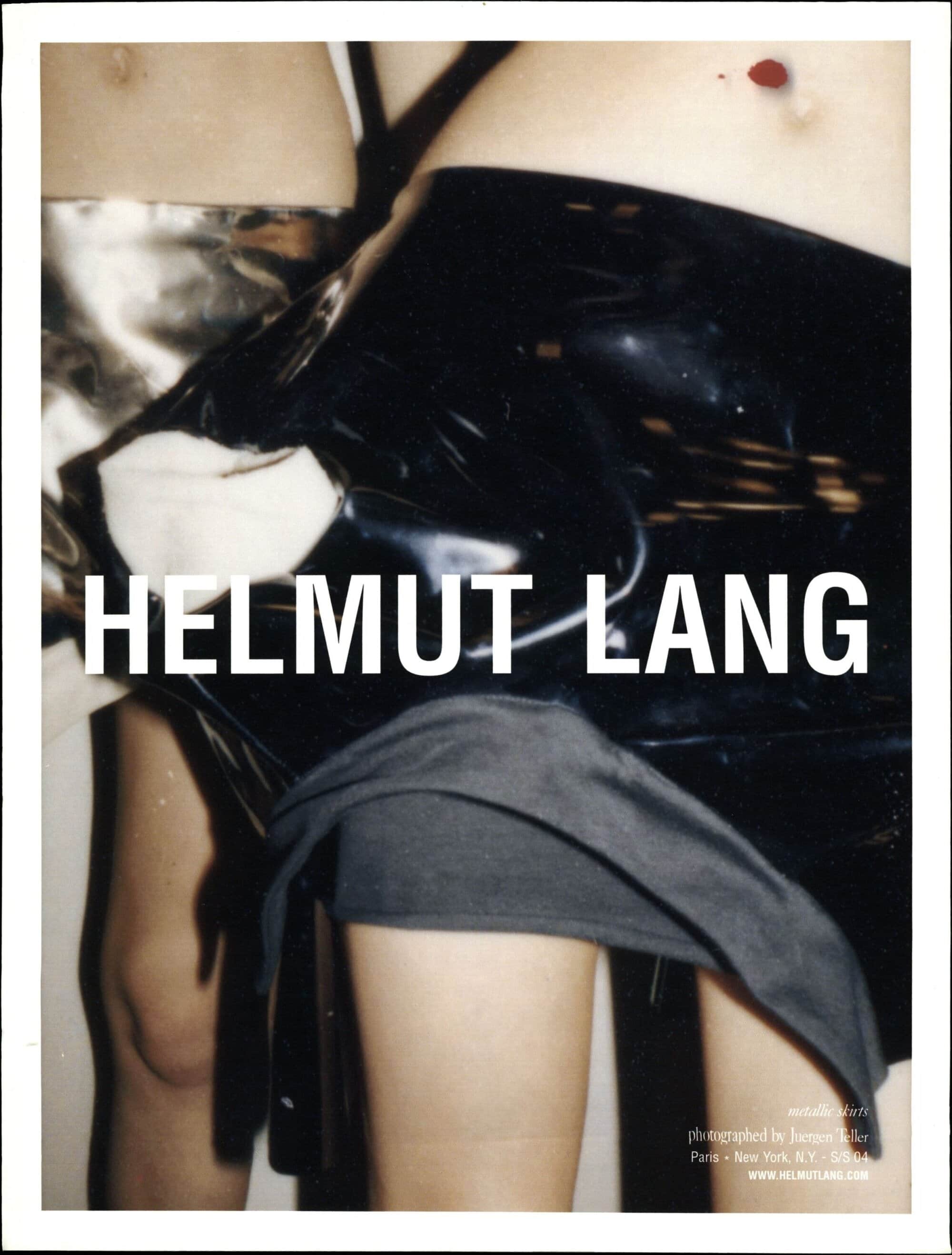

Photographer: Juergen Teller, Paris, 1997

Depicted person: Kirsten Owen, Paris, 1997

Courtesy of hl-art

For anyone who has ever built a show before computers did the thinking for you, it lands like a punchline and a love letter. I found myself explaining, half laughing, how those charts used to be made: pattern paper with dots, quick squares, little color-coded stickers you’d move around, sometimes the night before the show. It would take a team days. Seeing it enlarged, flattened, monumentalized—front row turned into evidence—makes you remember what fashion used to require: labor, choreography, restraint, nerves, and a kind of obsessive excellence that doesn’t photograph well but changes everything.

MAK Helmut Lang Archive. Courtesy of hl-art.

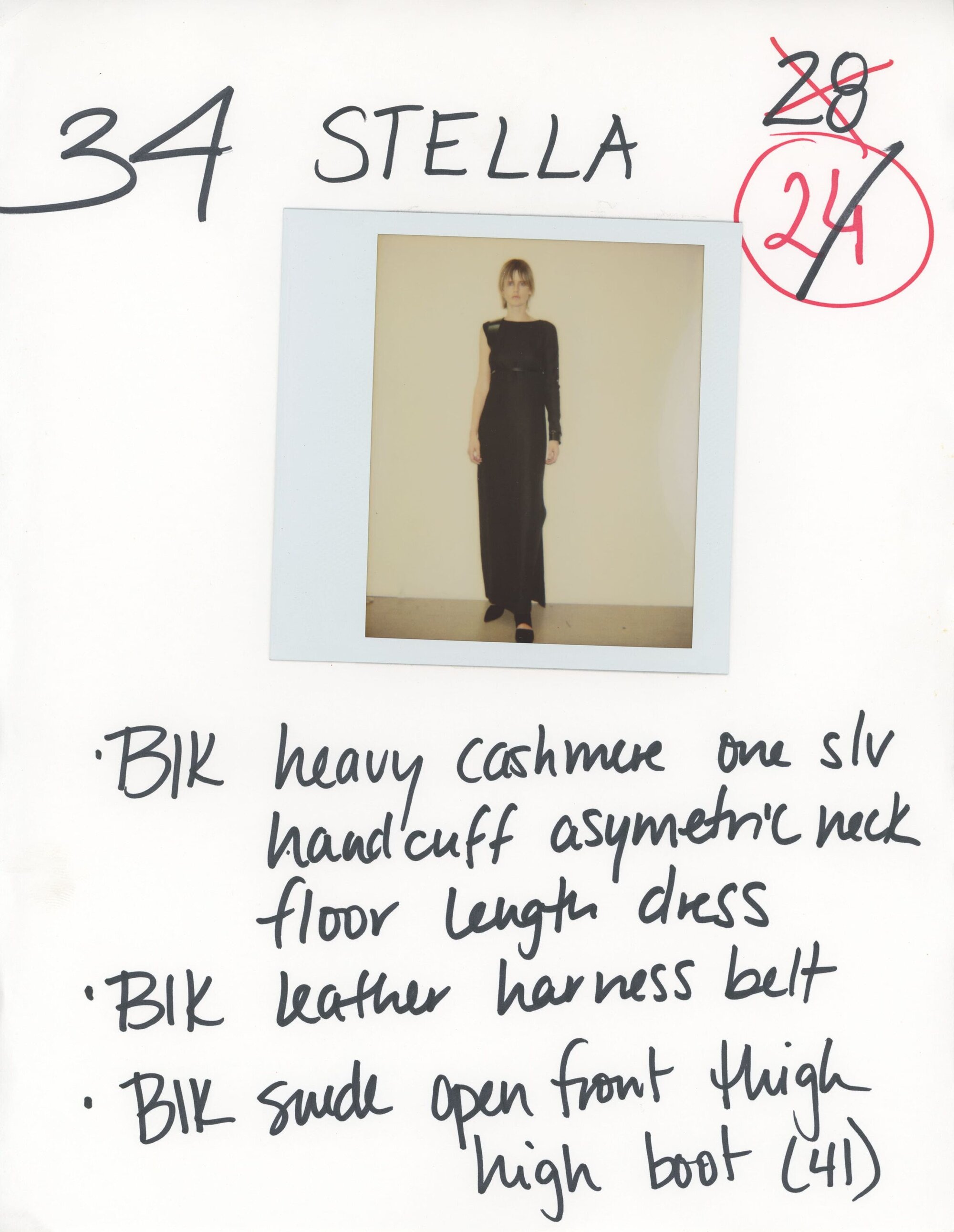

MAK builds around this with show footage, Polaroids, backstage images, and the kinds of artifacts the industry forgets to honor because they’re too close to the work. There are also the unexpected internal documents that humanize the machine. One of my favorite moments comes via what the museum calls “celebrity public relations report”—the kind of inside-baseball memo that never leaves the team. Steinhäuber read from one dated December 13, 2004: “Spoke with Bill Murray, who’s been extremely busy these days… he’s busting out of size 54… he has put on a little weight, but assures me he will be back in shape soon after taking long walks…” It’s funny, yes, but it’s also revealing: luxury as a constant, meticulous practice of relationship, reporting, and internal storytelling. The romance is in the mundane.

Photographer: Juergen Teller, Paris, 1997

Courtesy of hl-art

The garments that do appear are treated like punctuation marks, not paragraphs. MAK has “about 2,600 items of clothing and accessories,” Steinhäuber said, but the show opts for a limited selection—pieces chosen to illustrate structure, deconstruction, and material intelligence rather than to satisfy fashion’s hunger for looks. You get the sense of Lang’s “essentialist” logic—the idea that he wasn’t doing minimalism so much as stripping down to function and prototype. Steinhäuber pointed to a jacket mechanism inspired by “a baby carrier mechanism,” and you feel it: his work often looks fetishistic or technoid, but the origins can be stubbornly practical. Workwear, heritage, “non-fashion” categories—reworked until they become modern.

Even the art works included carry the same idea of transformation rather than display. Steinhäuber explained the columns in the exhibition as born from aftermath: after the archive fire, Lang used “leftovers… of his former career as a material for his new art production,” inspired by something Louise Bourgeois told him: “materials… [are] here to serve you.” The show doesn’t just present a past; it shows how a past gets reprocessed.

MAK Helmut Lang Archive, LNI 1778-4-57. Courtesy of hl-art

And that’s why the absence of clothing feels so right. MAK doesn’t ask you to worship the garments. It asks you to understand the decisions.

Steinhäuber put it plainly: it’s challenging to make an exhibition that works for professionals, superfans, and the general audience at once. But this one does, because it’s not a costume drama. It’s a systems exhibition. It shows how a label becomes an ethos, how retail becomes experience, how advertising becomes worldview, how collaborations become cultural positioning, how backstage becomes mythology, how space becomes luxury.

Walking out, the lesson isn’t “Helmut Lang was important.” Everyone already knows that. The lesson is more uncomfortable, and more useful: most brands today have more tools, more channels, more budget, more data—and far less clarity.

What MAK ultimately shows is that Helmut Lang didn’t build a brand by multiplying touchpoints—he built one by mastering intention. Space was treated as value, not absence. Collaboration functioned as alignment, not decoration. Communication was authored, not optimized. Process was preserved, not hidden. For brands operating today in an environment saturated with content, speed, and performance metrics, the lesson isn’t to imitate Lang’s aesthetic—it’s to relearn his discipline. Meaning doesn’t come from saying more, launching faster, or chasing relevance in real time. It comes from constructing a system so coherent that every decision, from retail to imagery to silence itself, reinforces the same point of view. Lang’s blueprint reminds fashion that authority is built slowly, expressed quietly, and felt long after the noise fades.

Lang’s work, as MAK presents it, is what happens when you build a world with restraint, intelligence, and the courage to let silence do the selling.

HELMUT LANG. SÉANCE DE TRAVAIL 1986–2005 / Excerpts from the MAK Helmut Lang Archive

MAK Exhibition Hall

© kunst-dokumentation.com/MAK

MAK Helmut Lang Archive. Courtesy of hl-art.

This exhibition doesn’t just memorialize a designer. It quietly dares the industry to remember how to mean something again. In an era addicted to amplification, Helmut Lang’s legacy, as MAK presents it, is a reminder that the most powerful brands don’t chase attention; they create gravity. They build worlds that hold, systems that endure, and ideas that don’t need to announce themselves to be felt. The challenge offered here is subtle but profound: to trust restraint, to design with conviction, and to remember that meaning, once earned, travels further than noise ever could.