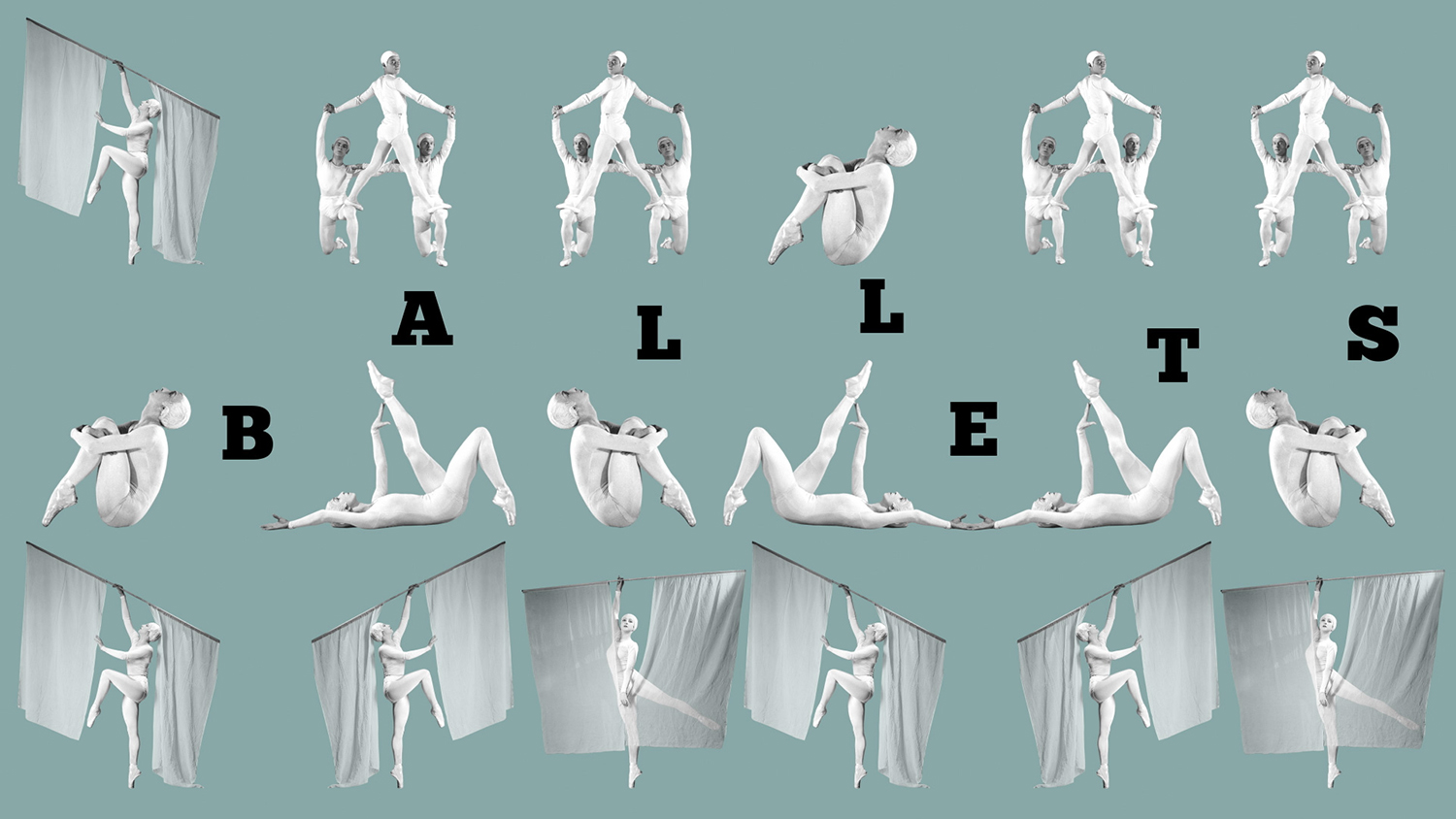

At the epicenter of the avant-garde, Gabrielle Chanel was surrounded by a circle of friends that included some of the greatest artists of her time, whose work and artistic disciplines nourished her creatively. Dance was undergoing a great revolution and there, Chanel found an echo of the fashion she wanted to offer women: a body freed so it mastered its movements, symbolizing a new kind of femininity. This art form mirrored her vision of women and the female allure.

This new chapter of Inside Chanel reveals the many artistic collaborations Gabrielle Chanel had with this major art form offering a retrospective on the interconnections between modern dance and the Chanel style.

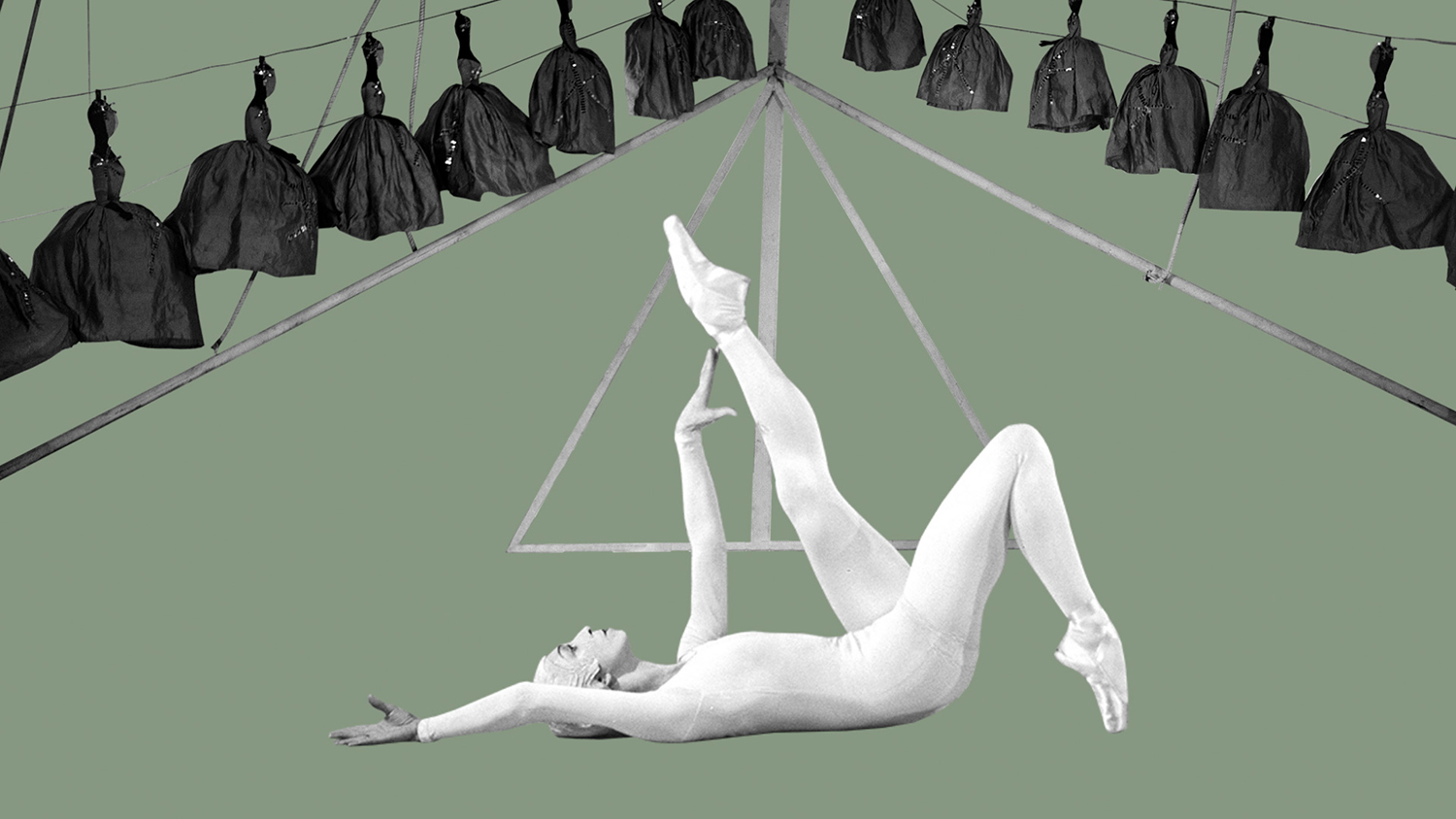

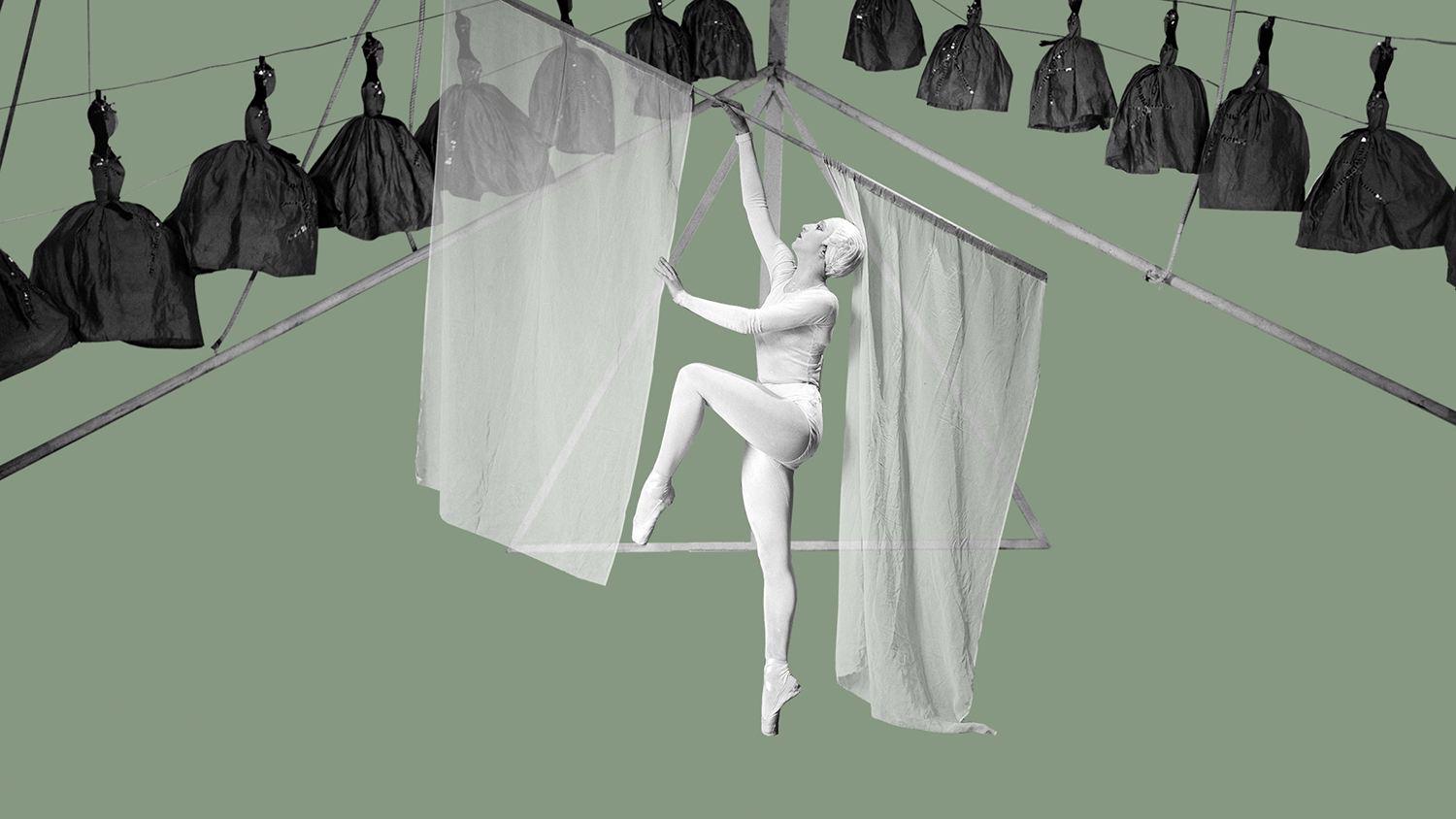

Like the cinema that was emerging at the beginning of the 20th century, dance opened up new paths for movement and artistic expression, illustrating its irrepressible quest for freedom. Gabrielle Chanel herself, who at that time was defining her style with comfortable and elegant clothes meant to liberate women’s bodies, followed dance lessons with the dancer in vogue, Caryathis. “Always remove, always strip away. Never add… There is no other beauty than the freedom of the body,” affirmed Gabrielle Chanel.(1) The grace of the dancers and their choreographies unhampered by their costumes, perfectly met the ambitions of the designer and her concept of a modern look, free from all constraints. Sharing the designer’s intuition, Isadora Duncan predicted that: “The dancer of the future would be the one whose body and soul had grown so harmoniously together that the natural language of the soul had become the movement of the body.”

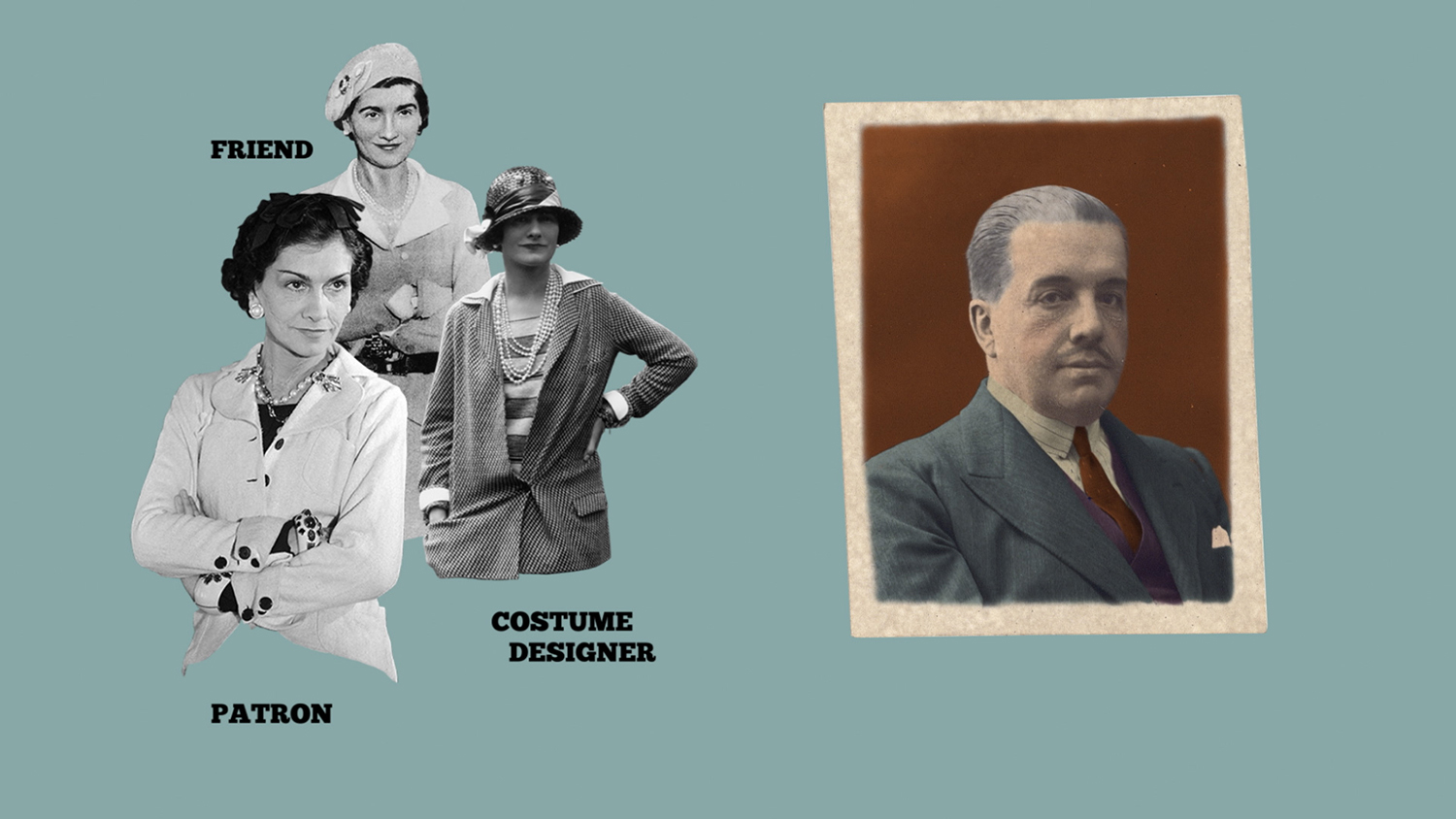

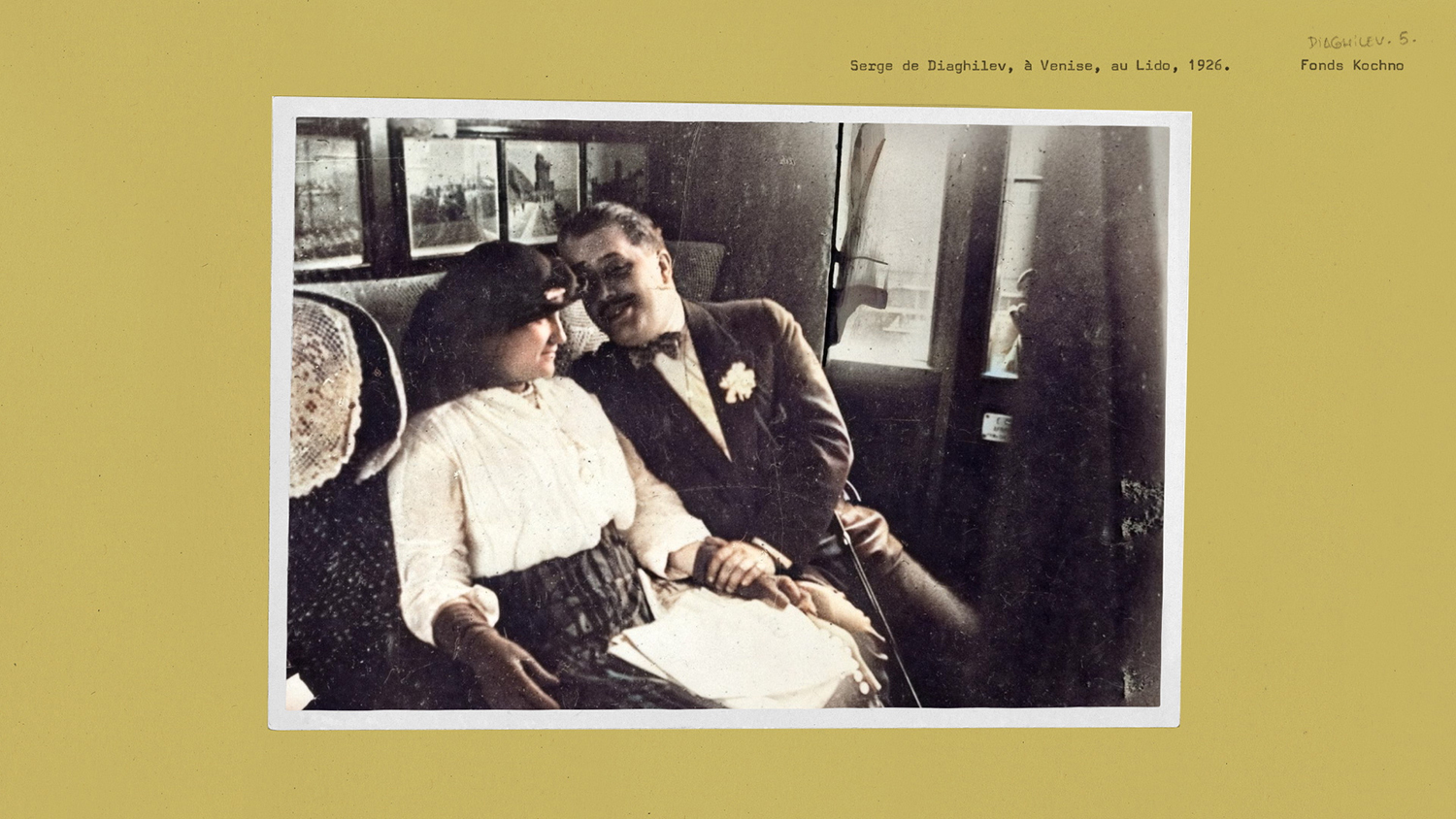

In 1913, Gabrielle Chanel experienced a profound aesthetic shock triggered by The Rite of Spring, presented by the Ballets Russes and led by the impresario Serge Diaghilev. Set to music by Igor Stravinsky, the performance was a total rupture with the classical ballet tradition and resulted in a huge scandal. Chanel had met Diaghilev in Venice while in the company of her great friend Misia Sert. She wholeheartedly espoused the innovative vision of a multi-faceted art form that mixed dance, music, painting, sets and costumes. It signaled the beginning of a longstanding friendship that lasted until Diaghilev’s death in 1929, and produced numerous artistic collaborations, with the reprise of The Rite of Spring being the first. It was indeed Gabrielle Chanel who would help mount a reprise of this seminal ballet again in 1920. Requiring total discretion and anonymity, she sealed her first act of patronage.

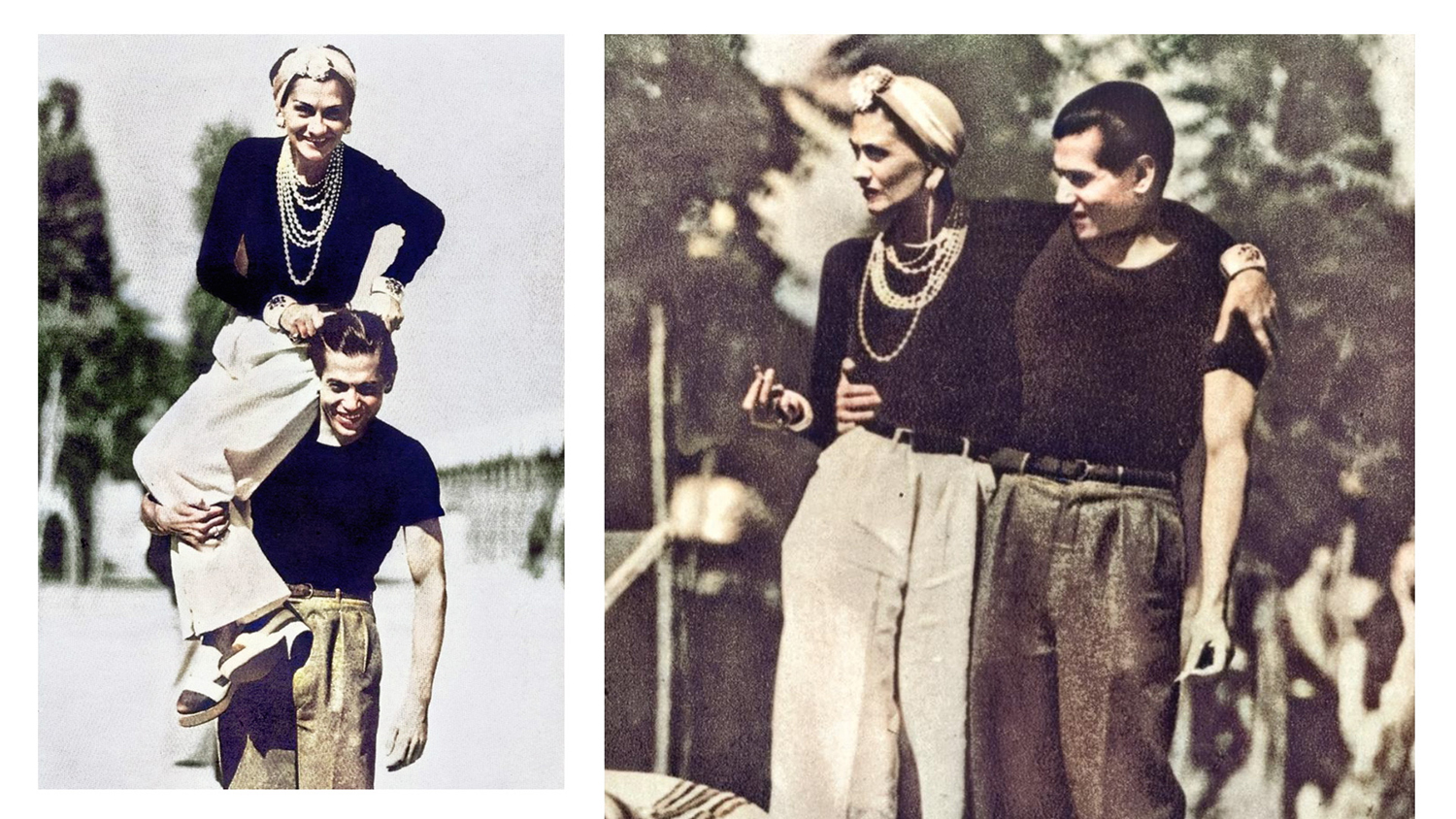

“In our ballet, dance is only one element of the show, and not even the most important one … the revolution we have undertaken in ballet, perhaps has less to do with the specific field of dance than it does with the sets and costumes.” Serge Diaghilev’s words were used to open the centenary exhibition of the Ballets Russes at the Paris Opera in 2009. They perfectly sum up the spirit of the Parisian avant-garde and also reflect Gabrielle Chanel’s desire to infuse movement and life into the looks she created for women. Her encounters led her to work closely with the visionaries of the dance world, and in particular with the Ballets Russes as her artist friends had done. In 1924, Gabrielle Chanel, in the company of Cocteau and Picasso, put her audacity to work for the Train Bleu, a satire on the Roaring Twenties.

The outfits she designed for the swimmers, the golf player and the tennis champion appeared as if they were ready to be worn for the actual sport. Directly fitted on the dancers, her outfits illustrated the accuracy of her vision of a fashion freed of its shackles and in touch with real life. This sound vision was further strengthened by the infinitely supple silk tunics Gabrielle Chanel designed in 1929 for the second creation of Diaghilev’s Apollo Musagète. The score was by Stravinsky and the lead role interpreted by Serge Lifar. Even after the death that year of her great friend Diaghilev, Gabrielle Chanel would never forget the world of dance. In 1939, for the “Ballets Russes de Monte-Carlo”, she designed the costumes for the ballet Bacchanale and Dali designed the sets.

The grace and freedom embodied by dance would regularly creep into Gabrielle Chanel’s creations. By combining dance and fashion, Gabrielle Chanel synthesized two creative forms marked by the transient and the ephemeral, going beyond the notion of clothing literally in movement, to benefit the female body once and forever freed.