INSIGHTS

By Long Nguyen

Fashion can shape and evolve cultural, societal, and personal values.

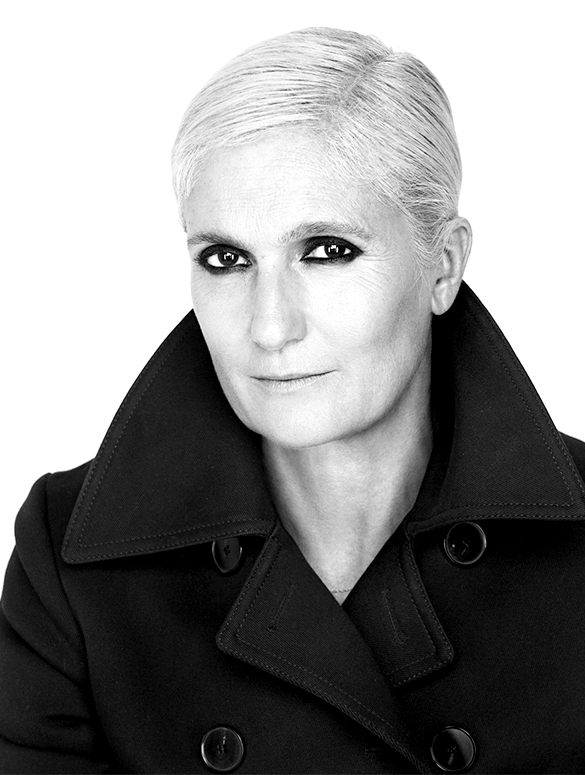

The most memorable look from Maria Grazia Chiuri’s debut show for Spring 2017 was a simple one – a crisp white tee-shirt with the words ‘We Should All Be Feminists’ printed in large capital letters at the front as a nod to the 2014 book by the same title, by the Nigerian writer Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, paired with a white shirt and a black long sheer tulle skirt embroidered with gold threads of animals figurines like crabs, swans, snakes, lobsters, and horses. It was not any of the white fencing looks that opened the show denoting the new sporty feel of the clothes; neither the lighter Bar jackets with light pockets nor the simplified evening dresses deliberately made so that these physical garments impart the sentiments of a new era that focuses on the younger generation of consumers.

Spring-Summer 2017’s look 18 – fashion’s parlance for the order of exit at a show coming out towards the middle of the first half of the show – was a decisive moment, a moment that started a reorientation of sorts for the Dior brand, the first concrete sign of Chiuri’s long term deployment of arts and letters to enforce the intellectual backbone of the shift towards softer and more feminine aesthetics for the Dior brand. This shift is critical to align Dior’s values with young consumers‘ values, and the house’s coveted the new consumer base.

For this younger generation whose influence will be dominant in the next half a decade, it isn’t enough to sell them extremely well-crafted products, whether a nice dress, a new handbag, or the latest pumps; these ‘kids’ are attuned to the values of the brands they spend their money on. Now, Dior has slogans that consumers can identify with when they think about what the brand means.

A year later, the model Sasha Pivovarova opened the Spring 2018 show on a stage decorated with mythical female figures drawn from the American artist Nikki de Saint Phalle, wearing a white and navy striped long sleeve sailor tee-shirt with the words ‘Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists’ printed on the front paired with washed denim pants and a denim cap. The American art historian Linda Nochlin wrote those words in a seminal essay of the same title in 1971 to expose the institutional barriers that have prevented women from achieving the same stature as male artists throughout the centuries of western art.

“I have been interested in incorporating words and sentences in my work, especially on t-shirts within my different collections: this iconic role of the t-shirt from the 1960s and 70s is something I relate to strongly. It’s one of the most efficient ways to demonstrate the communicative power of dress. And I love to use it to promote the works and ideas of thinkers and authors who have inspired and guided me,” Chiuri said from Paris when asked about the importance of having words written on her clothes.

Chiuri’s embrace of feminist art is about fostering an intellectual anchor in her quest to change in how to continue the Dior heritage codes – the New Look and the Bar shapes for examples – as each of the designers since the founders have done in the past: Yves Saint Laurent, Marc Bohan, Gianfranco Ferrè, John Galliano, and Raf Simons, each with a different interpretation of the 1947-1957 heritage, but rather a shift in how these codes can be seen in a completely new perspective from the female point of view.

Dior’s aesthetics have always been that of men looking at women and that of men dressing women.

At Dior, the heritage is so firmly rooted and the fashion codes of the New Look, of line A, of line H, of the Oblique, or the Tulip, defined by the specific silhouettes of clothes for more than a generation that required little alterations. Chiuri understood that these heritage dress forms have to evolve, that women today are not so easily captured by these rigid formulas for clothes. Chiuri has moved her collections in the direction of a trajectory towards the abandonment of these rigid structures of clothes such as the corset-body structure of the New Look – from her first couture show for Spring 2017, where the longer skirts and shorter sleeves introduced a finer but less confined set of jackets and skirts, to the Spring 2019 show with the dance troupe from the Tel Aviv based choreographer Sharon Eyal and her troupe of dancers who swung around as the models walked, in their jersey body-hugging soft flou dresses.

Chiuri’s clothes over her seasons so far at Dior, regardless of how one views her work and irrespective of the diverse opinions, have been actually very consistent – she provided her consumers with a recognizable signature look that despite their surface alterations from one season to the next remained solid in their foundation so that the Dior consumer can understand what they are buying.

“The message, really, is that there is not one kind of woman,” the designer said in September 2016. What emerged wasn’t a predictable chocolate-box repackaging of ladylike house codes, but a refreshingly widened viewpoint, inclusive of the sporty and the fragile. The balance between the two led to a whole series of relatable, simple, practical pieces aimed at drawing in a new audience.

Fashion innovations are great for the runway’s hype and great for amplifying the collection online, but these kinds of fashions may not be the kind of clothes that consumers buy. Yes, maybe it’s hard to imagine so many customers buying the many versions of sheer tulle skirt looks that manifested in different ways in each of Chiuri’s shows; but take a look at the undergarments seen behind the sheer tulle like a white-with-colorful-graphic-print corset and white shorts with printed purple heart from Spring 2018, or the sleeveless Bar jacket and shorts with a black crochet sheer long skirt from Spring 2019. That’s where to find the commerce, beneath the purple sheer tulle pleated skirt, because that skirt endowed the corset and short with a ‘Dior’ imprint.

This is one silhouette that Chiuri repeated in every one of the 20 collections she has shown since arriving in 2016 – the fitted top paired with a long tulle skirt. The crisp white fencing jacket embroidered with black bee motif worn with a white short and a flowy white transparent tulle long skirt from the debut Spring 2017 show, to the color-striped loose kimono Bar jacket with the black tulle skirt with metal thread stripes from the Spring 2021 collection.

From a design perspective, it may be easy to say that all these looks with the bubble tulle skirts took as their origin the Miss Dior outfit from the Spring-Summer 1949 trompe l’oeil collection that featured a similar shaped dress embroidered flowers. The 1949 flare dress is a rigid construction, unlike the fluidity and softness of Chiuri’s silhouette: this is a critical difference, first to introduce the notion of softer femininity, then to craft the clothes to correspond to this choice of a more feminine aesthetic.

The fitted top and full-skirted bottom look continues its passage through all of Chiuri’s collections, with some alterations here and there, but on the whole, the designer kept the outfit intact. This is the process of building her particular signature style that can be recognized as her own rather than an interpretation of the house’s heritage but a look that also speaks Dior to the brand’s consumer.

Examples abound from other collections that reinforce this softening approach – a black and white wide windowpane single-breasted jacket and printed black sweater and black shorts with a black tulle skirt with white lace trim from Fall 2018; a tan and black side-striped layered sheer organza dress from Fall 2018 Haute Couture; the tan sheer layered tulle strapless corset dress from Spring 2019; the white Bar jacket, the white shorts, and white polka-dotted shirt with grey dotted tulle pleated wrap skirt-belt from Spring 2018; or a green plaid cropped blouson, black leather shirt and shorts with a floral embroidered black tulle skirt from Fall 2019.

All of these black or brown tulle bubble or pleated or layered skirts were deployed to serve the purpose of rendering a softer Dior style that had always favored more of the structured and constructed garments. This softness defines a new way for customers to look at these new clothes, with silhouettes that may be a gentle departure rather than total adherence to the house’s codes, a departure that now needs an artistic foundation.

Art is a way to shift how fashion is seen.

Chiuri employed the visual craft of these feminist artists as a mean, an intellectual way, for her to break through the design boundaries at Dior, not just based on her gender, but primarily to sustain her work to break the mold of the rigid structural clothes just as the artists themselves struggle to eliminate boundaries in society and culture. She is explaining her thinking by using other visual artists’ works that share her sensibilities and her objectives, with the clothes wrapped in an aura of feminist art.

Art is part of my creative process. But beyond serving as a source of inspiration, I conceive each collection as an opportunity to engage in a creative dialog with artists – from authors to painters, from choreographers to filmmakers.

– Maria Grazia Chiuri, Creative Director of Dior

Chiuri said this from Paris, of her collaborative process in reaching out to other creatives from different fields. “It’s vital and inspiring to me to understand other creative practices, the specificities of each art: how you create a story with images, music, or movement. I am really drawn to these conversations as I feel fashion has this unique ability, historically but even more so today, to embrace these collaborations,” she said.

The artists that Chuiri has chosen to align her Dior point of view with are artists who challenged the art establishment for their independent voices and visions, artists like Judy Chicago, Tomaso Binga, Claire Fontaine, Penny Slinger, or Luca Marcucci, and artists who are not exactly in the mainstream but rather in a niche and subculture category.

In early March, Dior launched the house’s first podcast series titled Dior Talks to dive deeper into conversations with these women artists that Chiuri has worked with each season. “All the artists featured in the podcasts have collaborated with me for a collection: whether it was for the set, the music, or the campaign. The podcast series we have released so far tells their stories. I was interested in having them share their experiences and put into words their own work and our collaboration,” Chiuri said of the reason for the audio project.

“I also wanted to do an entire series dedicated to the women whom I commissioned to shoot my collections: I only work with women photographers as I believe this “female gaze,” to quote Laura Mulvey, is something so important to reflect on in the world of fashion today. It’s the way we, as women, shape our identities through this prominent visual culture,” Chiuri said of Dior Talks now in its 5th season, starting with feminist art, heritage, female gaze, jewelry, and the on-going Lady Dior Art project since late 2016.

“The way to give voice to the artists that I like and it’s the way of the future to have these conversations with a new generation of women,” Chiuri said in the opening podcast of the Dior Talks series that focused on feminist art. “I grew up in the 1970s Italy, which is a period of revolution of feminism,” she mentioned in the podcast about intense battles over authorizing legal abortion in 1974 with clashes between old and younger generations with opposite views about the woman’s body. The designer spoke about working at Fendi, where five women were her bosses, but they gave her a platform for pushing creative work supported by these independent and strong women around her, including her mother, who had a small fashion business.

“I choose them because it is a part of the journey of my life at Dior, not about any specific collection,” Chiuri said about her involvement in meeting with artists like Judy Chicago, Penny Slinger, and Tracy Emin, artists that she personally loves, and artists that she personally work together to bring forth collaborative works that are both intellectual and also beautiful.

Upon finding the book Exorcism by the British-born American artist Penny Slinger, Chiuri commissioned her to work on the stage for the Fall-Winter Haute Couture show in July 2019 at the Avenue Montaigne headquarters just before the closure for a complete renovation. Slinger, known for her work in different mediums including photography, film, and sculpture, transformed the Paris headquarters into a Dior Golden House with college fostering a hypnotic and surreal grey. White painted scenography based upon Slinger’s exorcist book and the series of ‘Doll House’ sculptures created in the mid-1970s that took the idea of a child’s toy and transformed into an adult one, with miniature houses named the Exorcist House, the Bird House, and the Red House.

The final look from this fall 2019 couture show was a house-shaped dress in gold fabrics that recreated the entrance façade of the Montaigne historic building. “Instead of a bride look, we have a marriage of element and building and the feminine represented by this wearable dollhouse dress on her body,” Slinger said.

“It was the biggest collage I have ever done. I decided to make alchemy that represents the feminine essence that is so significant and relevant not only as of the muse but as the whole work that’s behind all the creations,” Slinger said of the impetus for her redecoration of the building. “I imagine all the earth elements on the stairway – sacred trees, pictures that I have taken [over] many years and making a tree of life coming up the stairs and reaching into all the rooms and with women intertwined within the branches,” Slinger said, and mentioned the ventricular photographs of women in different elements of earth, water, air, and fire, in each of the rooms with a feminine sculpture holding up the entire structure.

Inside a white sculptural space built in the Museé Rodin gardens is a large brown rectangular banner with red trim with the words What If Women Rule the World? embroidered in dark brown threads with handwritten cursive lettering underneath a floral carpeted floor. “These are questions that are being asked all over the planet,” the artist Judy Chicago said of the banners that included a series flagged on both sides of the aisles, each asking other questions like La Terre Serait-Elle Protégée? (Will the Earth be Protected?) or Would God Be Female? Placed inside the white oval womb with a snail-shaped back container structure, she built and titled ‘The Divine Goddess.’ Chicago worked with Chiuri to create ‘The Divine Goddess’ not just as a stage for the Spring-Summer 2020 Haute Couture show but as a brand new work of art that she has thought about for over forty years has not had the chance to bring to completion until the collaboration with Dior.

“Dior was very far ahead when he was designing,” Judy Chicago said of the work of the house’s founder. “Women can no longer just be subjects themselves today, and women want something else now – a concept of mind.” Chicago said how she thinks Dior has been able to look ahead and install Chiuri as the first women’s designer in the house’s long history. “The artwork is a long commitment to the empowerment of women, where the banners are made by women in India in a school supported by Dior,” Chicago said of the Divine sculpture inspired as an homage to goddesses throughout history that is her most important work since The Dinner Party created between 1974 and 1979 – a triangular table setting with the names of the 39 most influential female figures in history along with another 999 names inscribed on the table – now on permanent exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum in New York.

“This is also the first collaboration with a fashion brand that produced a new artwork,” Chicago said of her efforts fighting for women artists to get credibility and acknowledgment for their works that male artists normally received for centuries. “The suppression of the feminine historically has let of an off-balance culture all around the world, and to move to a more equitable future there has to be a period of discovery and celebration, and there has to be a social and cultural embrace of the feminine defined by women, not the feminine defined by men.”

Chicago said that simply having shows is not going to change art history. Chicago mentioned the institutional resistance to the elevation of women artists in the male-dominated art industry and said that her works are not in major museums like the MOMA in New York. The Divine Goddess opened to the public the day after the show in late January.

“In Rome in the 1970s, there were riots every day. Life was politic then – the way you dress, they could tell if you were left or right according to the kinds of dress you were wearing,” said Paola Ugolini in Episode 3 of the period of the early 1970s Italy where the intense struggle against patriarchy, for example, elucidated the power of art as a means of personal and societal expressions and bringing these expressions to new generations. Dior sponsored the ‘Io Dico Io’ exhibition curated by Paola Ugolini at the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea, or commonly known as La Galleria Nazionale in Rome, that featured works from Italian feminist artists.

“Patriarchal society is a trap for women and also for men. A woman’s body is a battlefield. Femininity is a cultural construction,” Ugolini said about the current cultural conditions. “Fashion show is a performance and ideas about looks. Art and fashion are not the same things. Still, they can dialogue,” the curator also said about how Chuiri has to bring her own sensibilities and her roots to meet the Dior heritage. “It was an intensely creative moment. You can’t just tell people what to wear – it’s much more than that,” Ugolini stated.

A painted version of ‘Io Dico Io’ against dark grey background graced the entrance to the tent for the Dior Fall-Winter 2020-2021 show. The artist collective Claire Fontaine -Fluvia Carnevale and James Thornhill – created colorful neon messages around the square stage for the show with words and phrases in capital letters with text-based artwork and visuals to provoke thoughts on current issues across the globe. The duo used their concept of ready-made signs and symbols to form an installation of criticism to create the stage with neon signs – CONSENT, PATRIARCHY = CLIMATE EMERGENCY, FEMININE BEAUTY IS A READY MADE, PATRIARCHY KILLS LOVE, WOMEN RAISE THE UPRAISING, WHEN WOMEN STRIKE THE WORLD STOP, WE ARE ALL CLITORIAN WOMEN, and WOMEN’S LOVE IS UNPAID LABOR – and covering the floor of the Tuileries tent with actual copies of the French center-left newspaper Le Monde.

In March 2019, Tomaso Binga, the Italian multi-disciplinary artist, visual poet, and professor born Bianca Pucciarelli, read a poem in Italian while her younger naked body delineated the different letters on large print photographs, spelling verses from her poems that decorated the ecru set of the Dior Fall-Winter 2019-2020 show. In Episode 5, Binga, best known for her seminal Alphabet works in 1976 using her naked body to form the letters of the alphabet to compose statements against sexism and male hegemony in the art world and beyond.

“How gestures can communicate. I wanted to make the word with my naked body, which would mimic the letters of the alphabet to adapt to the body of the word – the word had a body and let’s give it this body,” was how Binga explained her alphabet work. “Some of the words work were considered obscene at the time. The woman’s body has always been the erotic body, the body of love, the body of possession,” Binga said of using her body in a sense that it’s a body that acts and talks. “Chiuri saw my paintings, and she wanted a woman who has worked with her body,” said Binga of meeting with Chuiri at her house and starting the process of making a larger human size alphabet which she titled Monumental Poetic Alphabet.

“I have never followed fashion, and I saw a world that’s completely different,” Binga said.

“There is a big difference between the past and today. Now there are no groups, no new movements – futurist, Dadaist, surrealist, conceptualists, writing, etc. – just a bit of afterthought. I don’t sense the presence of groups anymore,” Binga said about the lack of any underground art scene today.

Not only did Chiuri have the artists decorate the stages of her fashion shows to communicate and to affirm show after show via art images and art words, but the American painter Mickalene Thomas also made colorful mixed media collages crafted with glittering beaded embroidery on the Bar jacket for the Cruise 2020 collection as well as creating one of the new Lady Dior art bags, now part of the fifth season podcasts – jacket and handbag that put the essence of her known paintings Le déjeuner sur l’herbe: Les trois femmes noires, a collage take on the original Impressionist Édouard Manet masterpiece, onto Dior merchandises. In Thomas’ 2010 painting, the three black women become the subject gazing at the world, not cruised objects.

The American artist Vicky Noble together with Karen Voble recreated a few of her 1970s ‘Motherpeace Tarot’ deck of cards celebrating the ideas central to the Goddess movement at the time, linking progressive thinking with the mysticism and the occult – ‘The Wheel of Fortune’, ‘The High Priestess’, ‘The Sun’ – and crafting them into sleeveless dresses with colorful tarot prints, rainbow-colored Lady Dior bags and jewelry necklaces for the Cruise 2018 show in the California desert.

“Chiuri saw the sacredness of my images, and she understood profoundly about feminism, and she’s a pioneer in the ways she has gone back and resurrected the work of the 1970s. The tone of that tone and the tone was so strongly feminist. We started to create positive images of the way women could be empowered in society – it was folk art, not studio art,” Noble said of her work in Episode 7.

In Season 2 of Dior Talks that was launched at the end of April 2020 “Mes chéries: The Women of Christian Dior” the co-hosts Oriole Cullen, the curator of Modern Textiles and Fashion at the Victoria & Albert Museum in London, and Justine Picardie, a biographer, and editor, discussed the critical importance of two of the most influential women in Monsieur Dior’s life – his mother Madeleine Dior and his sister Catherine Dior. The Victoria & Albert Museum hosted the second leg of the exhibition Christian Dior: Designer of Dreams in spring 2019.

“It’s an idealized image of France and women before the wars. This garden in Granville is also an idealized image of the past – it’s a stolid villa in Normandy overlooking the sea. The garden is at the center of their childhood,” Cullen said of how Dior’s mother grew up in an era at the end of the Belle Époque society where the family patriarch inherited a fortune made from fertilizers, and the family lost their wealth during the depression era. “The brothers and sisters shared the love of the gardens, then things changed,” Cullen said of the changes in both fortune and the coming of WWII.

“The return of his sister Catherine and the end of the war gave Dior the impetus to do something on his own. Paris and France had to find a way to be proud again,” Cullen said of Dior setting up the business in 1946 with the backer of a textile magnate. “He set with Christian Dior at a time when fashion was in tatters, and Paris fashion was decimated then. Piccardie said the three women critical at that juncture at the new house were Raymonde Zehnachker, whom he had worked with at the house of Lucien Lelong and she became his studio director; Marguerite Carré was his technical director who translated his sketches into actual clothes, and Mitzcah Bricard [was] the head of a millinery who occupied a nebulous position at the house as the muse in the second episode titled ‘Sense and sensation: The Story Of Three Distinctive Dior Women.’

In the third episode ‘Stability and superstition: The Women Who Guided Dior’ Cullen and Piccardie spoke about how Dior hired a childhood friend from Granville, Suzanne Luling, to be in charge of sales and PR, and the mysterious Madame Delahaye, a clairvoyant and tarot card reader who had given much advice during the war years. “These women provided stability even after his passing to nurture the young assistant Yves Saint Laurent. Dior represented the return to luxury to France after the war,” Piccardie said.

Madeleine Dior

Catherine Dior

Madame Delahaye with Christian Dior

“The New Look had roots in an old look which is a nostalgia of the Belle Époque, but it took Carmel Snow to launch it to being the ‘New Look,’ and Snow remained a very loyal supporter of Dior,” Piccardie said about the importance of women models and fashion editors who were behind Dior’s launch in 1947, in Episode 4 “Faces And Figures: Cementing The Fame Of Dior”.

For Season 3, Female Gaze, the British journalist Charlotte Jansen hosted the podcasts talking to the established women photographers who were chosen to lens Dior’s ad campaigns from Brigitte Lacombe (Fall 2017), Janette Beckman (Spring 2017), Brigitte Niedermair (Cruise 2020), Pamela Hanson (Fall 2018), Bettina Rheims (Spring 2017), Sarah Waiswa, Alina Marzazzi to younger newcomers like Mexican Maya Goded (Cruise 2019), South African Jodi Bieber (Cruise 2020), Hong Kong-based Lean Liu (Cruise 2021), the London-based Paola Vivas (Cruise 2019) and British Photographer Nadine Ijewere (Cruise 2020). Working with women photographers for all of Dior’s advertising campaigns allowed Chiuri to usher in how women are portrayed and seen by women in this generation.

“I want to create a different image of woman as a subject, not object,”

– Maria Grazia Chiuri, about the dialogue between the female photographers and the female models, in Episode 1 of ‘Female Gaze’.

“I like women photographers with different backgrounds,” Chiuri said about nostalgia-based imagery instead of what is now, where she used six young African and diaspora photographers for the Cruise 2020 campaign or someone like war photographer Christine Spengler to shoot the Fall 2018 campaign based on the spirit of the May 1968 uprising in France, and the British photographer Janette Beckman, famous for her images of punk youths, who shot the Fall 2019 campaign, a collection based on rebellious English youths.

In her influential essay ‘Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema’ published in the Brtish film journal Screen in 1975, Laura Mulvey incorporated the Freudian psychoanalysis concept of scopophilia – the pleasure of looking and being looked at – to formulate the notion of the male gaze in classical Hollywood cinema whereby the male was the subject of looking and the female on-screen as the object of desire and of the male ‘gaze’.

“The image of a woman as (passive) raw materials for the (active) gaze of man take the argument a step further into the structure of representation, adding a further layer demanded by the ideology of the patriarchal order as it is worked out in its favorite cinematic form – illusionistic narrative film,” Mulvey wrote in the conclusion of her groundbreaking essay over half a century ago. “My work is a reflection of the world and the society we live in,” Nadine Ijewere said in Episode 2 of the Female Gaze.

The Season 4 Dior Talks series focuses on jewelry and features Victoire de Castellane, the creative director for Dior Joaillerie since 1999. De Castellane opened the series in early November and discussed with experts from different fields – historians, psychiatrists, art critics, ethnographers – the personal and social meaning of jewelry.

The curator Olivier Saillard spoke in Episode 2 on the evolving history of jewelry and fashion. Even in the 19th-century men were decorated with as much ornamental jewelry as the women, and only in the twentieth century, this situation changed radically. For example, the disappearance of the brooch is a manifestation of the separation of jewelry and fashion where jewelry is worn on the body and not on the clothes – “Jewelry has disappeared from clothes” de Castellane said.

“Jewelry, especially with precious metals like gold, no longer needed the support of the clothes. Piercing has become something of a tribal genre like the tattoo, and this is beneficial to high jewelry,” Saillard said of how these trends among young people like bikers and rappers with their specific and personalized jewelry are helping in a way to bring back different forms of bracelets, rings, and necklaces.

“Men and women wore jewelry since the beginning of humanity – the presence of jewelry preceded that of paintings and sculptures,” said psychiatrist Vannina Micheli-Rechman about the role of jewelry and its relationship with the body. “For the Egyptians, the jewelry created an idea of sublimation of the body. With jewelry, there is less of a problem of dealing with say body issues like unhappiness with one’s body because it is not worn and the body is almost abstract.”

“There is also the question of the power relationship of giving jewelry between the sexes,” de Castellane said of how women can buy jewelry at different price points. “There is also this notion of transmission from one person like a family member to another,” de Castellane said about a ring that she has from years back with initials engraved inside. “It’s the idea of eternity,” Micheli said. “There are life and death in jewelry,” de Castellane said.

“In the middle ages, jewelry was a form of protection but also in purifying the body and each jewelry piece at that time defended the body physically and against obscure forces and links to the spirit,” George Vigarello, the philosopher and academician, said in Episode 4 about how men wore jewelry in combat as protection from dangers. “The perception of beauty then was linked to the enlightenment of the body and the luminosity of beauty and the summit of clarity and shine of the jewelry, especially in paintings.”

“Men then wore jewelry for status more so than women. Today, men wear jewelry with a double sense – to reveal the force and the tenderness side. This is the same for women as well with regards to jewelry as a deposit of strength and sensitivity,” Vigarello said of the evolution of how jewelry is viewed through different centuries and the idea of protection like how organic objects like shark teeth that resist destruction became necklaces.

The ethnologist Patricia Ciambelli spoke about the transmission of the heritage of jewelry that encompassed memories when a ring or a necklace was given different lives overtime to many of those who will wear them as the memory of the object lives on from generation to generation like a pearl necklace that voyaged through time. “There is something not too serious the way rappers and their fans wear jewelry today,” de Castellane said about this new wave. Donatien Grau, philosopher and art critic, mentioned that jewelry has a critical place in the history of art and how there is always two sides to beauty as toxic flowers and a rose with sharp thorns. “Light has to pierce the stone to shine,” de Castellane said of the Versailles collection she created in three different segments, with one collection with stones chosen to be lit with light from a candle at night that induce a different reflection than in sunlight.

“Jewelry is a form of life,” said Grau as they spoke about the relationship of transference.

“Each piece has its own story in a chain in the work process,” said de Castellane “and it is a refuge from the world.”

“Jewelry for me are objects that have the capacity to be eternal, objects de that shine, like little treasures that can take me somewhere else,” de Castellane told Éric Troncy, the art critic and museum curator, concluding the jewelry series with de Castellane on the creative processes. High jewelry is a real work of beauty, special handiwork, and or special materials; for example, the flower dies, but the flower brooch lives on. “For me, they are like friends that don’t talk,” she said of the pieces she had created over the two decades.

The ongoing Season 5 started in early December, the host Katya Foreman spoke with ten artists – Judy Chicago, Gisela Colon, Song Dong, Claire Tabouret, Ma-Thu Perret, Recycle Group, Chris Soal, Olga Titus, Bharti Kher, and Joel Andriano Mearisoa – who crafted new versions of the Lady Dior bag, the Lady Dior Art debuted in early 2017.

The Dior Talks series are a new kind of underground subculture that exists deep underneath the main pop-cultural thoroughfares, against the extreme noisy background of today’s warp-speed digital world.

“Chiuri is not only bringing the artists of that era back, but she is also tapping into the feelings and a wanting to express that feeling through the Dior creations and the settings for the shows,” said American artist Vicki Noble in Episode 7 of Season 1 (Feminist Art). Connecting with artists and intellectuals is actually a heritage at Dior since the founder was an art gallery owner before embarking on a fashion career.

Despite all the adventures that luxury brands have taken in the last years of intense digital investments, especially in the realm of social media, podcasts remain more or less untouched by brands opting for anything visual rather than audio to capture new audiences. The podcast is still the last frontier, although there have been languid movements towards this more archaic form of digital reach. It is surprising that virtually none of the fashion brands are exploring this open frontier, maybe due to the perceived smaller audience metrics, but a niche audience can be powerful.

Podcasts in fashion are still in their infancy forms as luxury houses are pondering the many steps needed to acquire new audiences. These Dior Talks on Apple Podcast, Spotify, Google Podcast, Stitcher, Tunein, and Podbay are perhaps the start of a strategy to reach beyond the obvious ‘fashion crowd’ to other audiences that may have been overlooked.

That Dior is investing in talking to a more sophisticated and intellectual crowd does not seem obvious at the start as the brand insisted that the podcasts merely provide amplification of the house’s creative direction, a footnote to explaining the complexities of the art base for each of the women collections as expressed in the construction of the runway staging to words and phrases printed on a few of the actual clothes. But the recent success of the post show Prada conversations between Miuccia Prada and Raf Simons was one of the biggest event of the Spring 2021 season in September. There is hope for podcasts for luxury brands but that would depend on cast and content.

Rather than joyful distractions made to stage the runway shows, these collaborations with artists are integral to what Chiuri aims to create, a female fashion aesthetic at Dior rather than a total reinterpretation of these artists’ deep heritage providing the intellectual and foundational support.

Dior has to be part of this new worldview in the same way that American designer Kerby Jean Raymond is drafting Black Americans’ social-cultural history into his brand’s fashion aesthetic expressions. The idea that luxury fashion isn’t just about expensive and highly crafted products but principally that luxury brands embrace both the traditional and the rapidly evolving values – social, political, and cultural – of their audience. Consumers purchase not just a Dior dress or purse or fragrance or sneakers but also the Dior’s culture and value as delineated first on the runway show then reinforced with these series of podcasts marking the brand’s foray into the podcast arena rarely used in fashion so far.

“She has been working with artists and giving women this platform. There’s lots more going on than just clothes for wealthy women, and Chuiri uses the power and vehicle of Dior to do good things, which is important. It has never been done before, and we are talking about the highest echelon of fashion,” the British artist Tracy Emin CBE said of Chiuri’s commitments to make a difference with the aid of voices of female artists in Episode 4.

“Artists can open a window to create new possibilities for coexistence and for gathering of people in a community, an idea very dear to me,” the Italian visual artist Marinella Senatore said in Episode 9, the last of the Feminist Art series. It is this window that Chiuri wants to open for Dior.