At Frieze Week, Prada Transformed King’s Cross Town Hall Into A Cinema Where The Spectators Became Part Of The Show

By Kenneth Richard

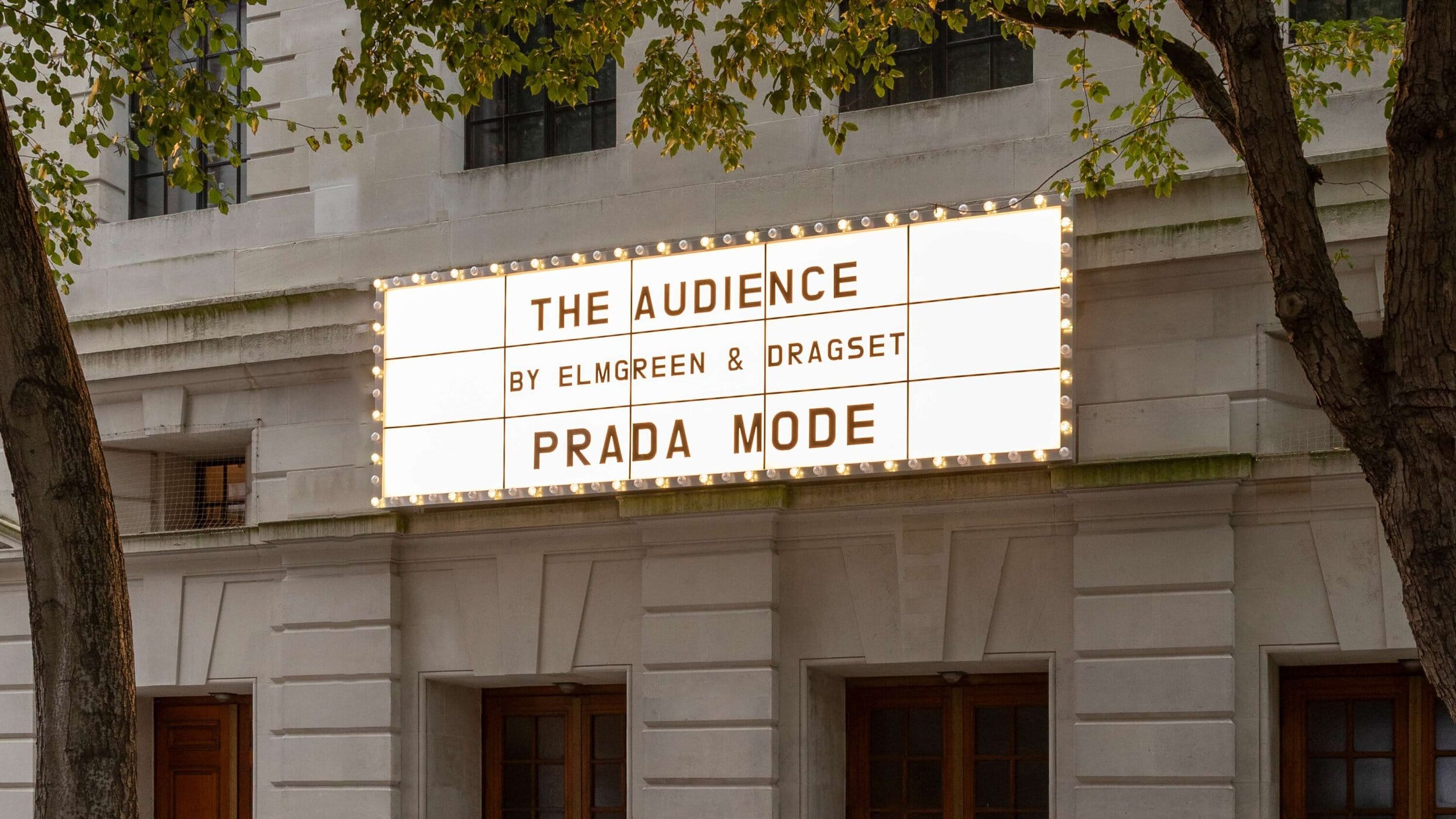

During Frieze Week, when art spills across London like champagne at an opening, Prada did what Prada does best — stepped into the cultural conversation with precision, wit, and intellect. For the thirteenth edition of Prada Mode, the Italian house transformed King’s Cross’s newly restored Town Hall into a theater of mirrors, where art and audience looked directly at one another.

The installation, titled The Audience, was created by Berlin-based artists Michael Elmgreen and Ingar Dragset, a duo long celebrated for turning public spaces into quiet provocations. They once built a full-scale Prada boutique in the middle of the Texas desert — a gesture equal parts surreal, social commentary, and architectural deadpan. For Prada Mode London, they brought that same blend of humor and human observation indoors, constructing a 104-seat cinema where nothing was quite as it seemed.

Inside, a film played on an endless loop — a scene that appeared to have neither beginning nor end, depicting a painter and a writer locked in dialogue about art, life, and their respective audiences. The image was hazy, as if caught mid-transmission, but the dialogue came through clearly, looping like a thought you couldn’t quite let go. Around the room, five hyperrealistic sculptures of audience members sat perfectly still, their attention frozen somewhere between fascination and distraction. Visitors took their seats among them, only to realize that they themselves had become part of the installation — watching the watchers while being watched in turn.

It was a meta-theatrical experience in the truest sense, a study in spectatorship that asked: what does it mean to pay attention anymore? The film blurred, the figures didn’t move, and the line between artwork and audience dissolved. As Elmgreen & Dragset put it, “Being part of an audience implies being one of many — sharing an experience within a spatial choreography.” Here, that choreography was both literal and philosophical.

Upstairs, at the Prada Mode café, another of the duo’s works extended the theme. The Conversation featured a young woman seated at a café table, FaceTiming with a character from the film below. The digital connection collapsed time and space into something eerily intimate — a physical sculpture locked in a virtual exchange. It was the perfect emblem of modern spectatorship: together yet separate, connected yet alone, living in perpetual observation.

Prada Mode’s brilliance lies in precisely this — its ability to build experiences that feel both profoundly cultural and unmistakably Prada. Rather than chasing novelty, the brand continues to align itself with ideas that endure: architecture, art, intellect, and a fascination with how we see. By commissioning artists who dissect perception itself, Prada places its audience — and by extension, its customers — inside the very question of what it means to look, to think, to feel.

Over its five-day run, Prada Mode London hosted a series of talks, screenings, and performances that deepened this dialogue. Cultural theorist Kirsty Sedgman opened with “Sit Down and Be Quiet,” a witty meditation on how audiences behave and misbehave, tracing the shift from noisy, participatory spectatorship to the silent reverence of modern viewing. Architect Elizabeth Diller joined Elmgreen & Dragset for “Performing Publics,” exploring how museums and civic spaces choreograph our collective gaze. Filmmaker Sir Isaac Julien reflected on the multiplicity of audiences — from the cinema to the streaming platform — while production designers Shona Heath and James Price dissected the delicate art of designing for an audience that might not even be real.

The result was part symposium, part performance, part surreal experiment in human behavior. You sat in a theater beside a sculpture pretending to watch, listening to real people discuss the nature of watching. The audience was both subject and object, framed and framing. It was impossible not to become self-conscious — of posture, of attention, of the act of looking itself.

And that self-consciousness was precisely the point. Prada Mode London wasn’t about telling people what to see; it was about making them aware that they were seeing. It was Prada at its most cerebral — not the logo or the runway, but the idea of fashion as a language of perception. Where other brands might sponsor art, Prada participates in it, using culture not as a backdrop but as a mirror.

As the film looped endlessly and the figures sat in perfect stillness, visitors came and went, whispering, thinking, smiling in recognition. By the time one realized that the true artwork was the collective act of sitting together in silence, the experience had already done its work.

In an age of fractured attention and relentless imagery, Prada’s quiet cinema in King’s Cross offered something rare: the luxury of reflection. For a few days, London had a theater where the screen didn’t matter as much as the gaze — where the most meaningful performance happened, quite literally, in the audience.