Interview By Obi Anyanwu

2018 is Kerby Jean-Raymond’s year. The Founder and Lead Designer of Pyer Moss is debuting his first collaboration collection with Reebok this season at Spring Studios, as well as the Pyer Moss Fall/Winter 2018 collection sans business partners.

Kerby took full ownership of his brand from his partners in 2017 and officially entered into a partnership with Reebok in the same year. To mark the new beginnings of the label, Kerby unveiled “the most magnificent durag of all time,” which is co-branded with Reebok, and he also released videos of rappers Vic Mensa and Kari Faux ripping up old contracts and documents and burning old clothes.

The bad juju is gone, the dead weight is lifted, and we expect Pyer Moss to take off into another stratosphere this year. This didn’t come together overnight for Kerby and his brand.

In just under five years, Kerby amassed several accolades and accomplishments under his belt, including the FGI Rising Star Award for menswear in 2014, the Forbes 30 Under 30 list for Art and Style in 2015, the Crain’s New York Business Class of 2017 40 Under 40 list, and is one of several fashion designers involved in the’ Items: Is Fashion Modern?’ exhibit at the Museum of Modern Art.

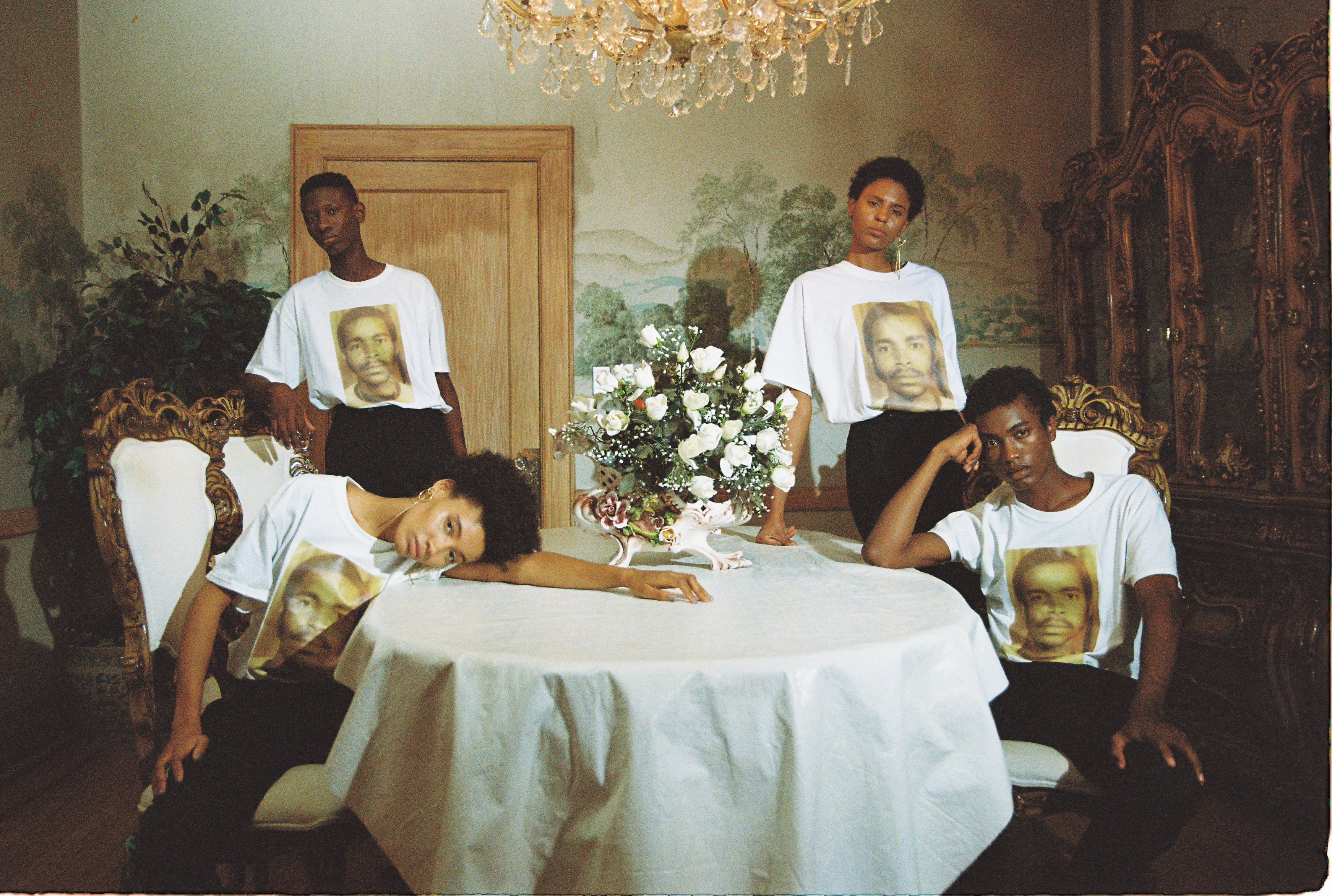

Many that are familiar with Kerby’s name and work remember his “They Have Names” t-shirt that he wore during the Pyer Moss Spring/Summer 2015 presentation and most likely associate the designer with the Black Lives Matter movement. GQ’s Citizen of the Year Colin Kaepernick wore a new version of the t-shirt named “Even More Names” for the GQ December 2017 issue.

What do the accolades mean to Kerby? Our guess is, not that much, but that doesn’t mean he’s not happy about them. To Kerby, the trophy is “the death of a hustle,” and all of his “trophies” are kept out of sight and out of mind. Instead of chasing praise, the designer uses his platform for social good, even if he shies away from fame.

We sat down with the designer in his Manhattan office to talk about Pyer Moss’ beginnings, taking full control of his label, using fashion as a platform to share his message, his Reebok collaboration and the Pyer Moss AW18 collection, which he describes as “the black answer to… Raf Simons’ ‘Americana’ for Calvin Klein.”

Obi Anyanwu: How did it all begin?

Kerby Jean-Raymond: I had just lost my job.

I prioritized traveling over my basic necessities and went to Ibiza twice, chasing this one girl around and doing wild stuff with my limited funds. I got back home to my apartment in Jamaica, Queens and thought, “What the hell am I going to do?” I think everybody hits that pivotal turning point. This was in 2012 and I was 25.

Obi Anyanwu: That sounds like the quarter life crisis…

Kerby Jean-Raymond: I hit that crisis. I knew I wanted to get back into fashion. I asked Anthony Hendrickson [of M65 and Third] to teach me how to use Adobe Illustrator, because I wanted to find a faster way to sketch. He sat with me in a Starbucks and taught me how to use Illustrator in an hour.

These programs weren’t really around when I had previously worked in the industry. Back then, I would draw stuff by hand and scan it in, and those old programs only allowed outlining. It’s not as intuitive as it is now.

I went home that night and started putting all of my paper ideas into CADs, and in two weeks time, every single inch of my apartment walls were covered in CADs for this brand named GAUD that I had started to conceptualize.

I finished the designs for what would become Pyer Moss, went to Istanbul on a recommendation to tailor leather, and came back with the camo leather jacket.

Obi Anyanwu: Ah, the Rihanna jacket right?

Kerby Jean-Raymond: Yeah, a publicist friend gave it to Mel Ottenberg, who gave it to Rihanna and that made us go viral. After she was spotted in it, we got a bunch of orders on the jacket and on the collection, and a lot of interest peaked on this thing before I even had a name for the label.

I actually decided on the name ‘Pyer Moss’ on January 28, 2013, the day that Rihanna wore the jacket. I passed on naming it GAUD, because it would be controversial in certain places so I decided to name it after my mother. I launched the website that day and we ended up rolling with that momentum.

Obi Anyanwu: Why did you decide to name it after your mother?

Kerby Jean-Raymond: My mom died when I was 7 years old, and I didn’t find out until I was 10. My family hid it from me—sometimes they would put my aunt on the phone to make me think I was speaking to my mom. Because of that, I still think about my mom every day. It’s like unfinished business. It was probably that I was thinking about her at that time and as I developed the brand more.

Naming the brand after her is a tribute. Her name was Vania Moss, but she changed her last name to Pierre, her cousin and sponsor’s last name, to get her green card. It made the process easier. I changed the spelling of ‘Pierre’ to ‘Pyer’ to not compete with Pierre Cardin in SEO drop downs. ‘Pyer’ is the Haitian phonetical spelling of Pierre. I wanted it so that when you spell ‘Pye,’ the brand would be the first result that would come up.

Now we don’t compete with anyone else, but it’s kind of funny how now I have a sculpture at the MoMA in tribute to Pierre Cardin when I was trying to stay away from him. Life comes full circle.

Obi Anyanwu: That sounds like God’s work again! There’s no other explanation really. How else do you reference your mother in the brand?

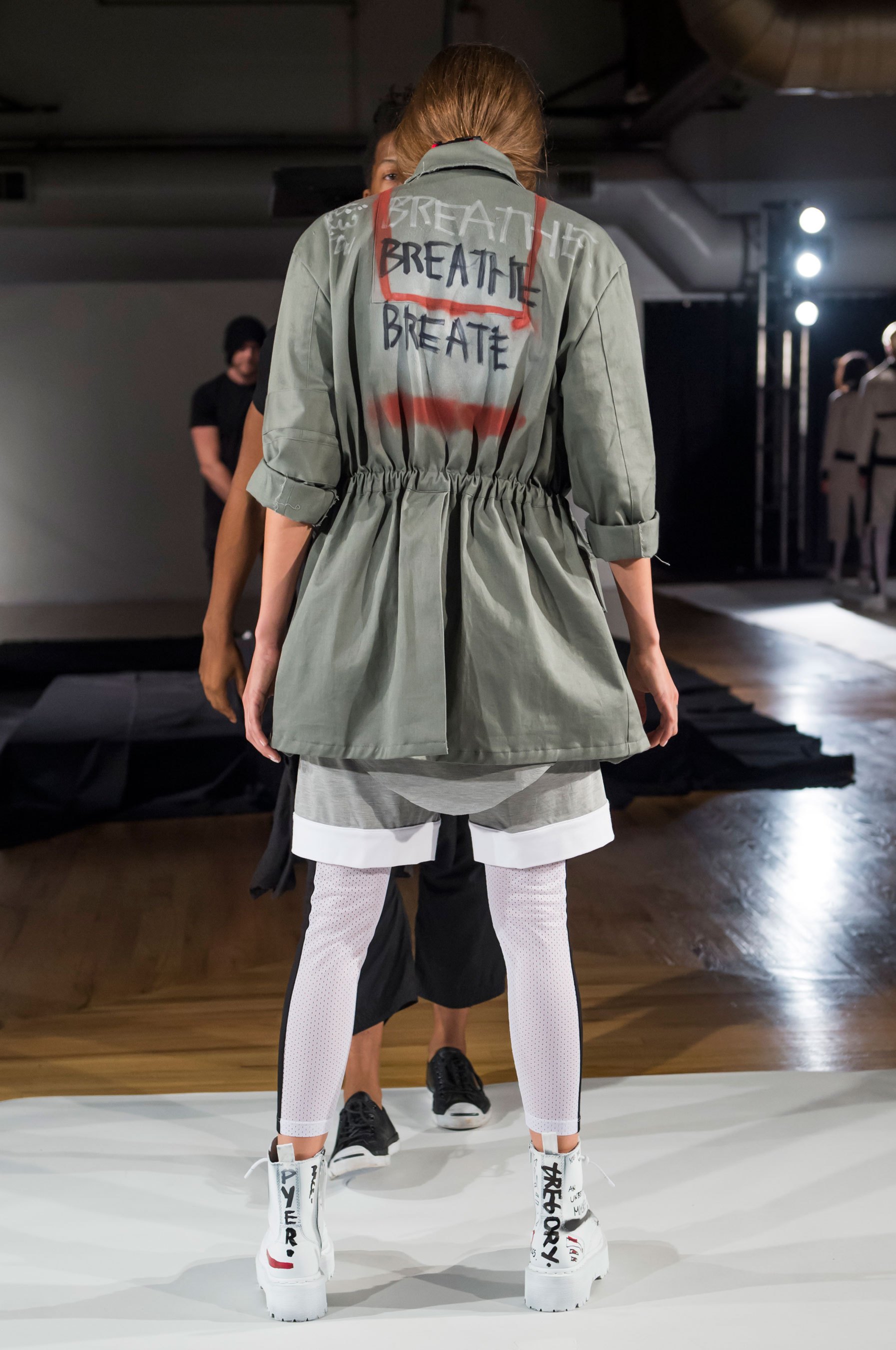

Kerby Jean-Raymond: The first branding element that I included when I was drawing was the rectangle on the back of tops and that’s because my mom used to make me these rectangular cardboard cutouts that I would use to help me fold my clothes neatly. That’s how she would get me to keep my clothes neat in the drawer. So when I did it, I drew the rectangular cutout as the apron on the back of all of the tops.

Pyer Moss developed out of necessity too, because I couldn’t get a fashion job due to my work experience being so far apart. My last experiences were in high school, but then college and law school messed that up so I couldn’t get a job.

Obi Anyanwu: What initially drew you to fashion as a teen?

Kerby Jean-Raymond: I wanted to be a sneaker designer. I’ve always been a sneakerhead. I wanted to collect kicks and design kicks. I remember telling my father that I wanted to be a designer or a shoe designer and he argued that there wasn’t any money in it, and he was holding a bottle of water when he said it. I said somebody designed that bottle and he looked at it and then stared at me and looked again and that was the first time that I felt like I upped him. And I stuck with it because I wanted to ride that momentum.

Obi Anyanwu: How was the process selecting fashion and design high schools back then?

Kerby Jean-Raymond: I remember going through the pages of the high school directory and stumbling upon The High School of Fashion Industries, which had a shoe and jewelry program when I signed up. They cut it right when I got into the school, and in the following year, they cut even more programs because of the terror attacks on September 11th. I started to act out. I was a raucous mess because I was so bored.

I disrespected a teacher by hitting another kid in class and she sent me to the principal who told me to have a conversation with her. My teacher told me that if I wanted to be in this classroom I needed to get an extra curricular activity, so she gave me the contact to her roommate, who got me an internship with her at Kay Unger New York. The internship lasted two weeks before it turned into a full apprenticeship and lasted another six months before it turned into a job. Kay Unger helped to start Marchesa and she put me on that project. I worked on it with her, Georgina and Karen when I was 16.

Obi Anyanwu: Your experience with Marchesa isn’t discussed much nowadays. What was the response like back then?

Kerby Jean-Raymond: I had press for my own projects when I was that age. I was seen as this child protégé. When I look back at those press clips—my father has 1 or 2 of them—they were kind of embarrassing because even then they focused on me being black and being in this underserved neighborhood. There was this German magazine that wrote “ghetto black youth” to describe me.

Obi Anyanwu: Oh no…

Kerby Jean-Raymond: It is what it is. The interest and draw there was that I was this black kid from East Flatbush, who wasn’t from a wealthy background, not being from any money, my parents being Haitian immigrants, and going to public school. I think everybody wanted to act like my Sandra Bullock in the Blind Side. As if they were discovering this diamond in the rough.

Honestly, the only person who I felt at that time was altruistic about wanting to help me was Kay Unger. The people that worked at Kay Unger were like family to me. I don’t think Kay ever looked at me like that. She saw me as her son, and now she’s still my biggest fan.

Obi Anyanwu: How would you describe your experiences now compared to when that line in the German magazine came out?

Kerby Jean-Raymond: I didn’t care then and I definitely don’t care now. My mindset has always been that the trophy is the death of a hustle. All of my trophies are in this drawer here or on the floor over there. I don’t keep anything to remind me of past achievements because it keeps me in that past state. It’s like chasing your own tail.

Obi Anyanwu: What about making the Forbes 30 under 30?

Kerby Jean-Raymond: Whatever.

Obi Anyanwu: But it was a goal wasn’t it?

Kerby Jean-Raymond: It was at the time, but I’ve grown so much since then. Making the Forbes list put a target on my back. That’s why I’m so skeptical of fame. My goal around finances is to pay my employees on time and to sustain a business where I can continue to give my team salary increases.

I don’t care about somebody else’s perception of my wealth. I’m fortunate to be in the position that I’m in now. I’m straight. Now we’re in a position where we can pace ourselves and take our time, and not rush to market. We don’t have to do anything strange or oddball-y.

Fame would come very quickly for Kerby. As the Pyer Moss audience grew, so did the number of killings of unarmed and innocent black men and women at the hands of law enforcement and/or vigilante justice. The murder of 18 year-old Normandy High School graduate Mike Brown in Ferguson, MO, led to protests that could not be ignored by news networks and publications, and the birth of the Black Lives Matter movement. Brown’s murder and acquittal of Darren Wilson, the police officer who shot and killed Brown, reminded millions of Americans of the ongoing and at times silent issue in this country that has claimed too many lives, as well as the misrepresentation and vilification of black men and women by the media. In response to the number of killings at the hands of law enforcement, Kerby made and wore a t-shirt to his Spring/Summer 2015 collection presentation that featured the names of many men, women and children that were killed by police officers and vigilantes, including Brown, Trayvon Martin, who would have turned 23 years old this year, and Eric Garner and Kimani Gray, who were both killed by New York City police officers. The “They Have Names” t-shirt took on “a life of its own,” according to the designer, and propelled the designer into a conversation of social justice.

Almost a full year later, Kerby used fashion again to make another statement on this ongoing issue with a documentary film on police brutality that debuted with a runway show. The film has been shown only once to date.

Obi Anyanwu: On this topic of fame, I feel like shortly after we first spoke, you started to appear in the press more. There was the New York Times, the Washington Post, and it really all started with the “They Have Names” t-shirt. How did you come up with the idea?

Kerby Jean-Raymond: I’ve always had these small art project brands since I was 14 or 15. I used to produce political statement shirts under the brands Mary’s Jungle and Montega’s Fury. When I made the “They Have Names” shirt, it was something that I personally liked and would like to wear. I made the shirt for myself and I had no idea that the reaction was going to be what it was and that it was going to take on a life of its own.

Obi Anyanwu: How did you navigate sending your message in an honest way despite the risk of people misconstruing your message?

Kerby Jean-Raymond: At first, I tried to pull away from it quickly. I said I wasn’t going to sell it. I was like please stop texting me and emailing me about this and then I had this epiphany. I thought, “Wait a minute, I got 150 different DMs and texts and emails… I have 150 people paying attention to me?” That was pivotal. I could do 1 or 2 things with this: I could run away from this or I could actually use this attention to bring awareness to the other things that I care about or actually help someone with this. It took me awhile to get to that epiphany, but once I got to that point I was able to figure out how to use my platform to help other people. So I did end up selling those shirts, and all of the proceeds, including what I put in to make them, went to the ACLU.

No one else is talking about these issues in fashion, which is a very powerful communication tool, and I’ve felt that I have this obligation as one of the only black people representing us in this space to go out and make a statement. My collection after that was called ‘Ota Benga,’ and I did part one at Supermarket in Tribeca, which was a presentation in July of 2015.

Obi Anyanwu: I remember the turn out for that. Great energy and crowd. I think Zoe Kravitz was there and George Lewis Jr. from Twin Shadow.

Kerby Jean-Raymond: It was crazy. It was a packed room, and I felt like, wow there are a lot of people paying attention to me. I didn’t think that the show was good enough though so I decided to do another one a few weeks later.

The team and I filmed a documentary with the family members of the victims of police brutality like Sean Bell’s fiancé and Eric Garner’s family. I was going to show the film in place of the runway show, and then at the last minute, I decided to put the clothing out. I wanted the clothing to look like a canvas. If you noticed the first six looks were this beige canvas. That was supposed to be the whole collection, and Gregory Siff and other artists were to come out and tag the outfits up. It didn’t work out that way, but it still turned out to be a really powerful show.

Obi Anyanwu: That time crunch is pretty intense though. A few weeks with market too.

Kerby Jean-Raymond: I think we shot everything in a week. It was 3 of us filming—we had an intern who was good at video, so I sent him to Florida to film two families. I filmed four families in New York City. Marc Ecko gave me some space at Complex to shoot, and we filmed his part there. We filmed Kay Unger at her apartment. We just showed up to different locations with a white background and asked if they want to talk about race.

I never released the video too. It’s one of those things where if you were there you were there, and if you weren’t you weren’t. That’s how I want my work to be. I want all of my shows to feel like that.

Obi Anyanwu: The documentary still resonates with me today, and I remember the experience so vividly without going back to look at my photos and videos. The number of people involved, the intro with Kendrick Lamar, the news truck outside of the venue. It was very effective. I could imagine it was difficult to use your platform for this.

Kerby Jean-Raymond: I had to start using the platform. That was the pivot from being a brand trying to chase trends and create trends to being a brand that has a voice. I’ve always personally had a voice—I brought the NAACP and different organizations to my college, and because my school was very segregated, I would host gatherings with black alumni. I’ve always been into this, but I just didn’t know that I could do it in a high fashion space.

I’ve been doing this since I was 15, so I thought that if people are into it then I should figure out how I could include it from time to time. It has taken a life of its own and I like where it is now.

Obi Anyanwu: How do you feel about people using their platform as well? For instance, Robert Geller released his ‘Immigrant’ t-shirt twice. Do you feel like you were the catalyst to it all?

Kerby Jean-Raymond: The whole point of me doing this was to bring awareness and to get people to do this as well, and I think that we definitely achieved what we set out to do in that sense.

I love seeing the designers that are doing it right like Robert Geller. He’s one of my favorites in New York City. It’s good to hear that he’s doing something like that and donating the proceeds where it matters. That’s important. I don’t like to see the big brands that see activism and activists as another target market.

They’re not seeing the root causes driving these people and it sucks, especially when you see activists show up in these campaigns and not finding out where the company’s revenue or their money is going to. Don’t take my sweat and my marching kindly. This shit is not free, and it comes with a social responsibility.

Obi Anyanwu: That’s very true.

Kerby Jean-Raymond: Everyone subscribes to a political agenda, but sometimes the companies are not donating any money. There is no shortage of people out there that need help, so why aren’t we evolving that conversation and taking it off of the runway and into the real world? Help these people instead of exploiting them. I’m trying to lead by example by the way that I do it. If it’s not directly affecting a cause and if it’s not directly affecting people, then what’s the point of doing it?

My friend Kimberly Drew curates the social media account for The Met and she has a rule that if she helps you build your personal art collection, you have to buy art from black living artists or donate to a charity of her choosing. There are rules of engagement. You just can’t exploit what we’re doing and not give back. It’s not gonna fly.

Obi Anyanwu: That’s a perk of being in demand, but it’s easy to shy away from the responsibility too. I remember when we first talked about the film I asked you what comes next? And you said you wanted to put the focus back on the clothes.

Kerby Jean-Raymond: At that time I was very clear that I wanted the brand to get back to being about me, and even the ‘Ota Benga’ collection was how I was personally feeling at the time. That’s why I went out of my way to make the documentary, because it was about how I was personally feeling.

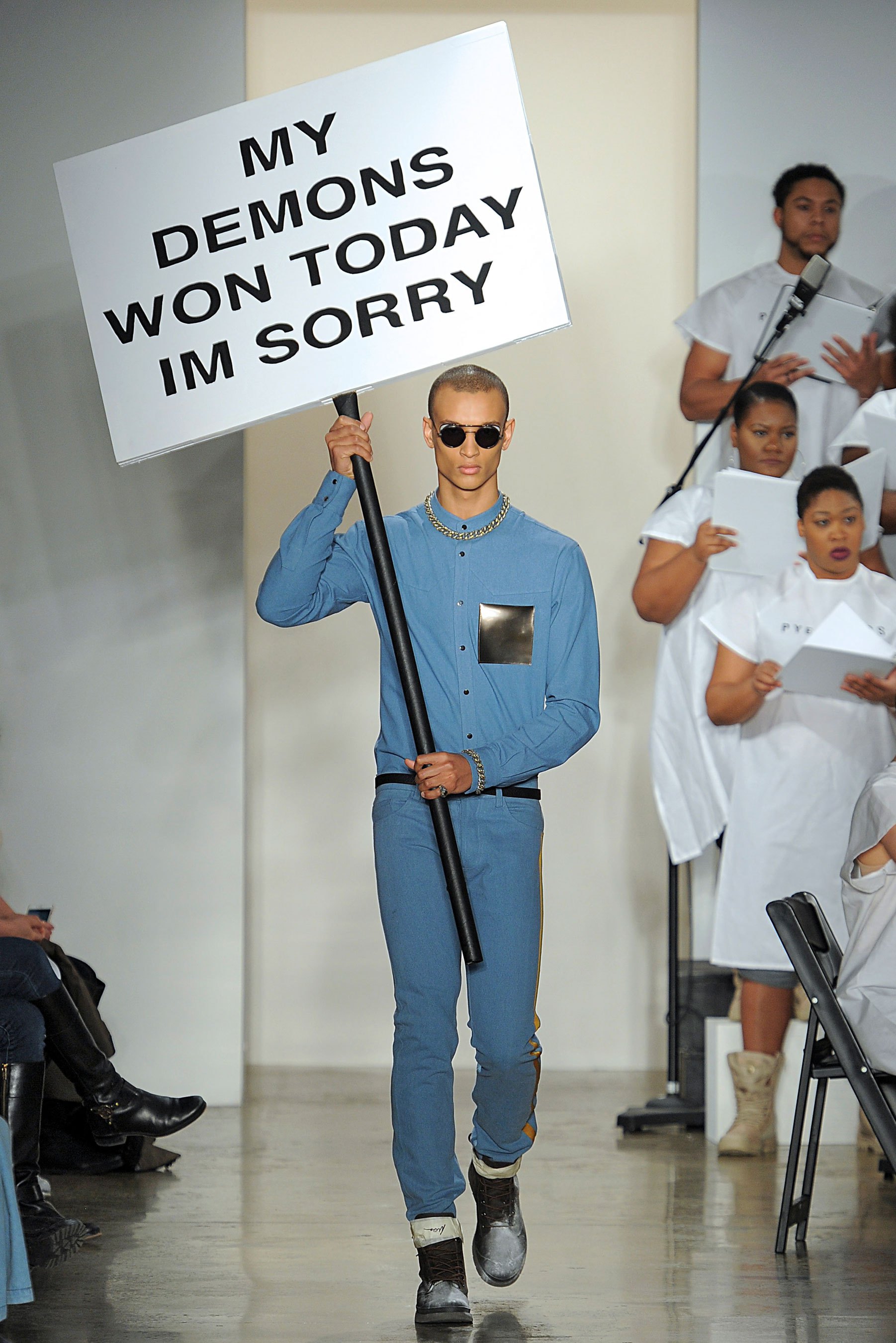

The next collection was about depression—the ‘Double Bind’ collection with Erykah Badu. That was a personal feeling, something that I was going through after receiving death threats for putting Black Lives Matter on the runway. It was like being put in this spot of fame that I never wanted.

Obi Anyanwu: The following collection was ‘Bernie vs. Bernie.’ Was the collection born from your interest in politics and law and the current social climate?

Kerby Jean-Raymond: ‘Bernie vs. Bernie’ was made during the time when my partners started to get really greedy and really made my day-to-day work life hell. ‘Bernie vs. Bernie’ was about a capitalist vs. an idealist. I was this idealist taking on these people who were here just to make money. Bernie Sanders vs. Bernie Madoff, the collection was autobiographical.

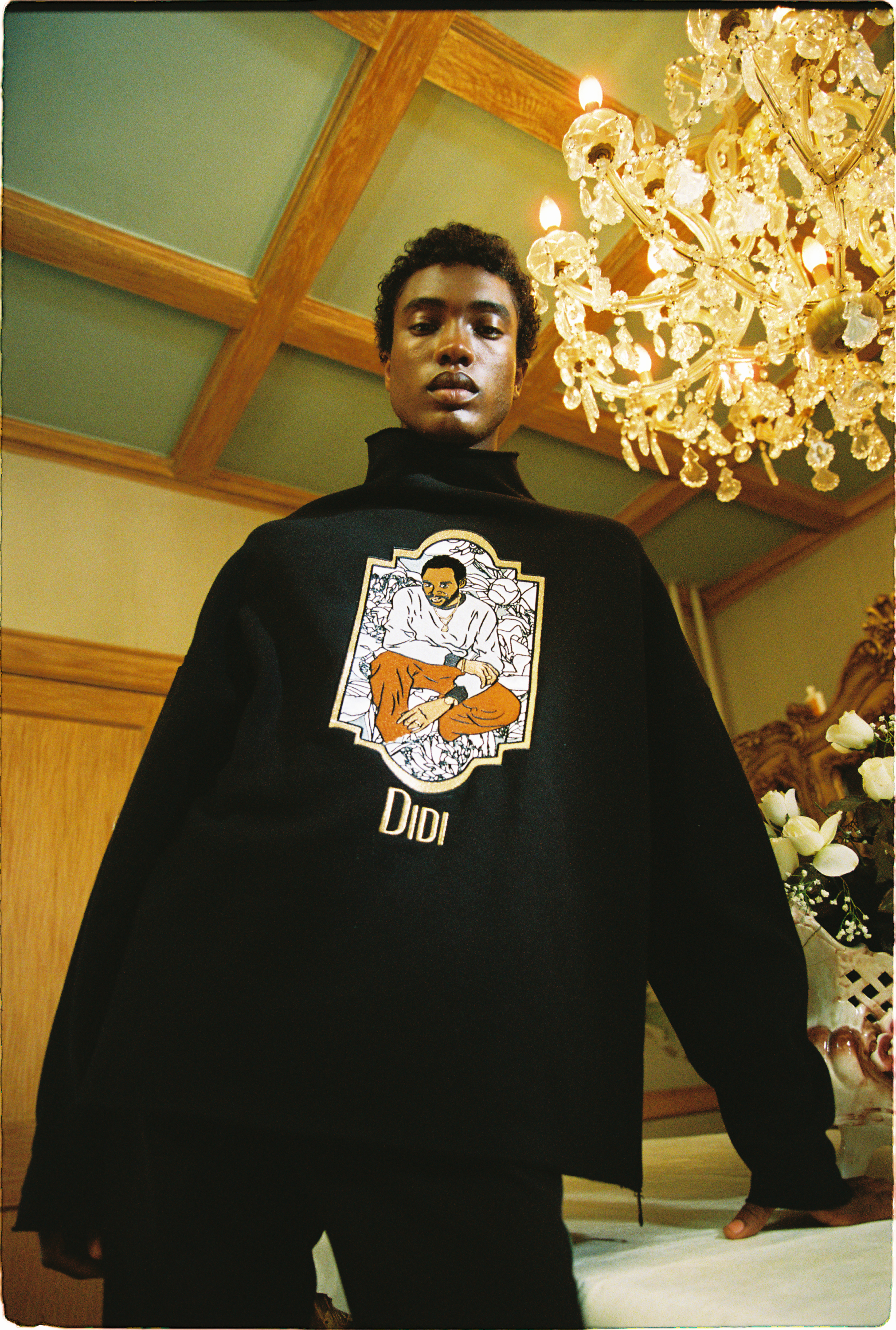

The next one, ‘Stories About My Parents,’ was also autobiographical. Fall/Winter 2018 is about my experience with the American flag and not feeling like I’m American even though I was born here and raised here. I think that, for most black people, we experience the American flag like the swastika.

Obi Anyanwu: I definitely think that marginalized groups in this country will understand and relate with that.

Kerby Jean-Raymond: Right. This collection called ‘American, Also.’ focuses on the other side of America. I think visually it’s going to look like the black answer to Raf Simons’ ‘Americana’ for Calvin Klein. When brands channel Americana, they omit the black presence in it. When they think Americana, they don’t think about black people, because they’ve been conditioned to believe that America is emblemized by Clint Eastwood and John Wayne and people like them when in actuality the original cowboys were black and the word cowboy was a racial slur.

These collections are always going to be personal. That’s the only way that I’m willing to design at this point. I’m happy that I did [the documentary] show. It took me a long time before I could even say that I’m happy that I did the show and made the t-shirt. The experience allowed me to create without remorse. Tell my story without being ashamed.

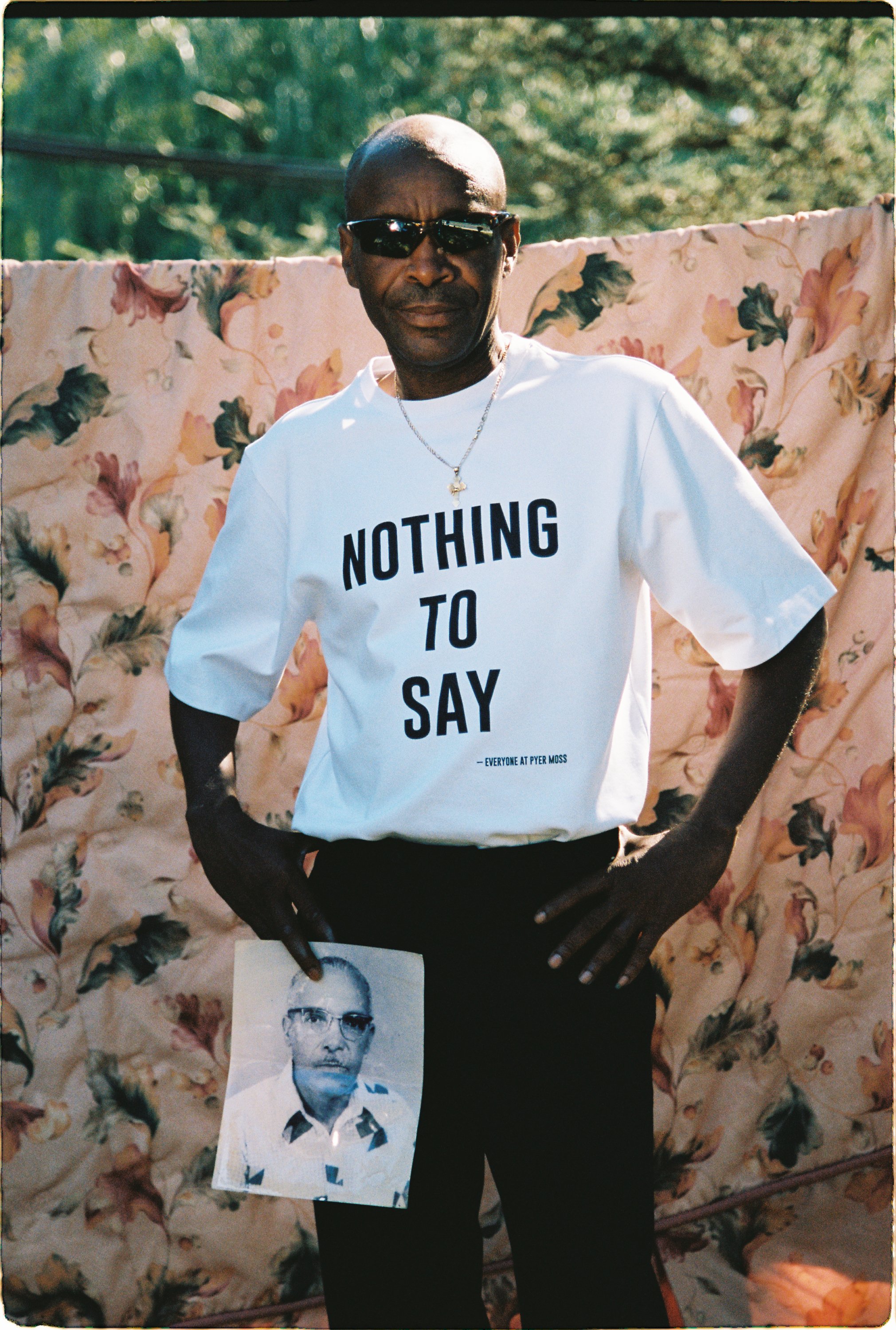

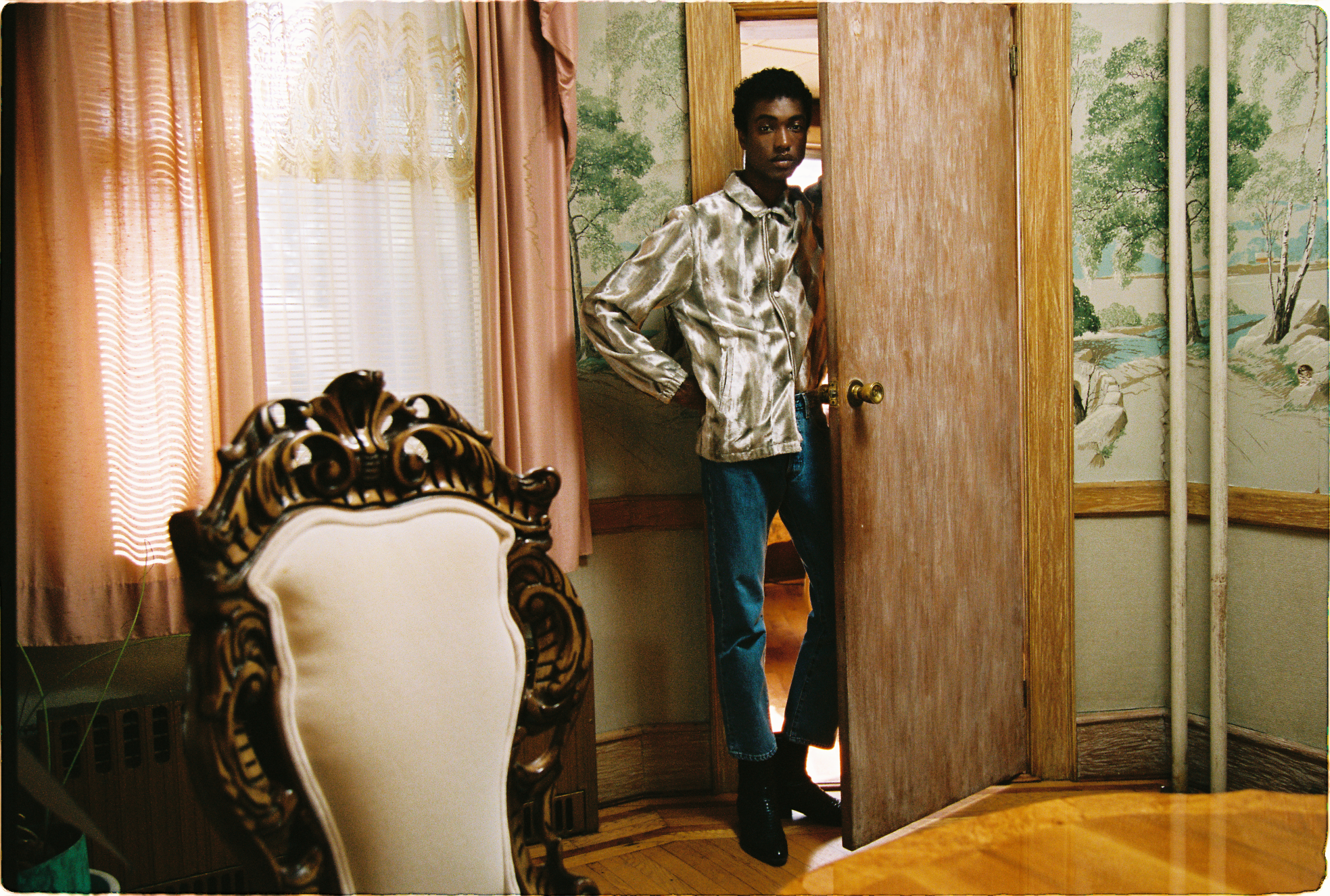

One of the stories Kerby told through his work is the story of his father, a Haitian immigrant that lives in Brooklyn. This personal story was supported by a campaign that was shot at Kerby’s godmother’s house. While the campaign made its rounds in the media, videos starring Vic Mensa, Kari Faux and Eddie Opara appeared showing ripped contracts and old Pyer Moss clothing on fire. The label also unveiled a new Opara-designed logo that Kerby describes as “the clear vision” of Pyer Moss. Rebirth.

Kerby fought to take full control of Pyer Moss and won, he secured a partnership deal with Reebok that is a first for all of the parties involved, and the label enters 2018 with a full steam of momentum. Possibly its biggest year to date begins at New York Fashion Week with the debut of the AW18 collection and the Reebok by Pyer Moss collection. Of course, the groundwork for this monumental year was laid several months earlier.

Obi Anyanwu: The documentary, the t-shirt, the responses both good and bad all lead to the brand’s new logo and direction. Why did you decide to change the logo now?

Kerby Jean-Raymond: I didn’t want anything to do with my old partners. I didn’t want anything that reminded me of them. If it reminds me of my mother then I’ll keep it, but if it reminds me of them then I’ll take it away. I feel like I was never able to establish a brand identity for Pyer Moss, because they were so focused on selling.

For example, the ‘Ota Benga’ collection had clasps to reference how Ota Benga was kept in the Bronx Zoo until 1906, and since that collection did well, the following collection that was about depression, had clasps as well. I’m referring to the market collection and not the collection that you saw on the runway. I’d have to force pieces to make sense within my theme.

Obi Anyanwu: That would prevent the newer collections from being cohesive.

Kerby Jean-Raymond: Exactly, it didn’t make sense so the brand always looked disjointed to me. Sometimes you have to go through showing what other people deem to be nonsense for a long time before it sells. You think about Rick Owens’ story or Gareth Pugh’s story, all of these different designers who showed ignored all buyers’ advice and kept doing what they were doing and eventually showed it big because people gravitated towards what is true to the designer. I wasn’t able to do that.

So now, I’m establishing the branding from the jump. I’ve changed the logo and picked logo colors that fit my attitude. My attitude is semi serious and that’s what the logo feels like to me.

Obi Anyanwu: Who designed the logo?

Kerby Jean-Raymond: Pentagram’s Eddie Opara. I think he did a great job and now we’re developing the concept further. We’re now working with an African artist named Anthony Konigbagbe, who helped design the new website and everything.

Obi Anyanwu: And what about the content that coincided with the logo change? What’s the story behind the videos?

Kerby Jean-Raymond: The content that we’ve created were ideas that I came up with on the day of. I called in our friend Gabe, who goes by the name All Rights Ain’t Reserved, and Tom Vogel, who had been shooting all of our videos and all of our content. The video with Kari Faux burning old clothes was an idea that I came up with on the day of. I wanted to show that the old clothes that you’re used to are what my partners used to make me do and this is what Pyer Moss is now.

Pyer Moss is about romance, storytelling, people, and humanity. You have Vic Mensa ripping up my old contracts and burning the lawsuits. You got Eddie Opara making the new logo and then you see what we are now. This is the clear vision of what I want Pyer Moss to be.

And it feels right now. The response for it has been good. It feels like we’re slowly building back.

Obi Anyanwu: The ship is better in your hands than in someone else’s who doesn’t understand your vision. And you secured the Reebok deal too. Can we get specific about the partnership?

Kerby Jean-Raymond: I have a blank slate at Reebok. We have certain metrics to hit to make sure this makes sense financially, but overall its freedom. The first thing you’ll see is Reebok by Pyer Moss, which releases in 2018.

It’s an opportunity that I could’ve only dreamed of. There will be some growing pains too since this is the first time that they are doing anything like this.

They’ve never had a designer come from the outside and rally their team to make something, and I have them really stretching their production capabilities, working with textiles and making things that they never thought they would ever make. You’ll see. We’ve really flipped the script on them. I have full respect for my team up there.

Obi Anyanwu: How did the partnership come about?

Kerby Jean-Raymond: I was actually in the process of doing something smaller with a bigger company. The big one. At the time, they were doing this equality campaign and they wanted me to be the face of it. The idea brought me back to the “ghetto black youth” comments and being pigeonholed into this conversation. I was keen to it because my partner wanted the money and the partnership would have done a lot for our notoriety.

I got lucky because Damion Presson, Marketing at Reebok, wanted to get me in a room to talk when I was about to sign. We met and I told him that I want creative control and my own sub brand under Reebok, and he said you got it, anything you need. We’ve been working on this since January, but the paperwork was just signed recently.

It’s crazy because when I was walking away from my partners I was going to walk away from the brand and start something new…

Obi Anyanwu: You were going to just let them take the name?

Kerby Jean-Raymond: I wouldn’t let them take the name. I knew that if I didn’t use the name then they couldn’t use it. I was going to let it die. Live and let die. But it worked out. Reebok said that they would partner only if I keep the name so I had to go into legal process with my initial partners. I had to go through lawsuits and all this legal shit to buy my company back, which I’m glad I did.

Everything worked out, and I’m really glad that I fought or else I would’ve felt like a real sucker walking away from Pyer Moss. There was nothing wrong with the brand; except for the way things were happening on the inside.

It’s not going to be perfect just because I’m in control. I’m still going to have my problems and there’s still going to be growing pains but it’s mine.