By Anna Ross

As fashion strives for a more sustainable future, end of life has become a hot topic and increasingly important for the economy. As much of retail slumps at the wrath of the pandemic, circular business strategies are exploding.

The Rise of Resale

Accelerated by an increasingly digitized era of consumption and growing consumer awareness around sustainability, second-hand sales, in particular, are on the up. Resale is due to experience growth of 69% between 2019 and 2021 (ThredUp), with the market expected to be worth over $60 billion by 2025.

Of course, once upon a time, luxury fashion often classified second-hand as second-grade, with worries over counterfeits, price control and authenticity. However, only until recently has luxury realized the potential in synergizing what used to be two very separate entities. For luxury, French consignment platform Vestiaire Collective was the catalyst for change. As consumers were confined to their homes throughout 2020, Vestiaire benefited from closet cleanses, cost-cutting and a growing audience of eco-conscious Gen-Z customers. As a result, they saw a 100% growth in just one year.

Companies like sustainably-minded Kering quickly grabbed a piece of the pie, acquiring a 5% stake in Vestiaire Collective this March, pushing the platform’s value to over $1billion. More recently, German e-tailer MyTheresa launched a new service that allows its clients to sell pre-loved items on Vestiaire in exchange for store credit. For both MyTheresa and Kering-owned brands such as Stella McCartney, Bottega Veneta and Balenciaga, these strategies could not only reduce waste, but present an opportunity for increased brand loyalty and awareness via buy-back schemes and store-credit. Both represent a shift towards a more circular future, where in essence, a singular garment can create repeated value, closing the loop while reducing fashion’s mounting waste problem.

Rent, Reduce, Repeat

It’s not only sentiment around consumption that’s changing; attitudes around ownership have shifted too. As consumers, we’ve grown used to sharing cars via apps like Uber and homes via platforms such as AirBnb, so why not share our wardrobes too?

Across Europe, spurred on by an ever more eco-conscious shopper, the market has come alive with new rental models, ranging from peer-to-peer platforms such as HURR, monthly subscription services like Nuuly and on-loan services like By Rotation and Rotaro, which allow customers to borrow ‘it-brands’ for a fraction of the RRP. Come 2019, rental was being hailed as the most conscious way to shop, dubbed by many fashion editors as the perfect antidote against fast fashion and the cure for buyers remorse.

Then came Covid-19. As the retail scene plummeted, shops shuttered, household name brands went into liquidation, and the joy of dressing up fell by the wayside in lieu of sweats and slippers, rental businesses gritted their teeth and expected a similar, painful nosedive. The exact opposite happened.

From March 2020, as most of Europe went into lockdown, rental app By Rotation noticed an uptick in its subscribers from 12,000 to 25,000, while the number of items listed by lenders grew by 120%. With consumers clearing their wardrobes and looking for new ways to make money, it seemed as if the pandemic had only further validated the relevance of the rental economy.

Although up until recently, the model has primarily been reserved for special occasions. Rotaro, who straddle both resale and rental, has captured the zeitgeist of easy-to-wear pieces, loaning out buzz-worthy brands such as Jacquemus, Saks Potts, and Cecilie Bahnsen from as little as £12. “Rather than only renting for a special occasion, our community is repeatedly renting to fulfill their desire for newness. It’s becoming a more mindful shopping habit, turning to rental rather than popping down to the high street,” explains Georgie Hyatt, who co-founded Rotaro in 2019.

Whatsmore, rental doesn’t just benefit the consumer, but brands too. “In an ideal circular fashion system, brands are producing less, but better quality garments, with the circular fashion industry in mind, profiting from repeat revenue through rental and reaching more people with fewer garments. For brands, it makes sense financially and ecologically as a brand can make 40% more revenue through rental, and they have to incur fewer financial and planetary costs of producing less garments,” Hyatt tells The Impression.

It seems the opportunities are endless for this booming market; this year, By Rotation tapped up a like-minded collaboration in a partnership with Page Hotels. “Aligning with our ethos, Page Hotels strives to be as eco-friendly as possible, pledging to only use sustainable materials in all aspects of the hotel,” says By Rotation founder Eshita Kabra Davies. Their partnership will allow Page Hotel’s environmentally conscious guests to rent the latest trends without the commitment of purchase, enabling them to benefit from a pre-booked or in-room rental for the duration of their stay.

Rental is taking off at retail too. This month, both Rotaro and By Rotation are hosting their first-ever physical pop-up spaces across London, while peer-to-peer platform HURR saw such success at Selfridges that it’s now a permanent feature. By Rotation’s Kabra Davies believes there’s plenty more to the rental market than clothes alone.

Our pop-up at Westfield London will also showcase rental furniture and homewares, celebrating the diverse opportunities for the rental market across fashion, home and lifestyle.

– Eshita Kabra Davies, Founder of By Rotation

With a wealth of buzzy brands and an ever-shifting consumer attitude, it seems the rental market is becoming a bountiful business opportunity for brands, retailers and consumers alike.

Fixing Fashion

One must never underestimate the old school. The “make do and mend” mentality has transformed from bare necessity to very much en-vogue. And with consumers increasingly shifting to a ‘buy less, buy better’ mindset, it makes perfect sense that what they do buy should last a lifetime.

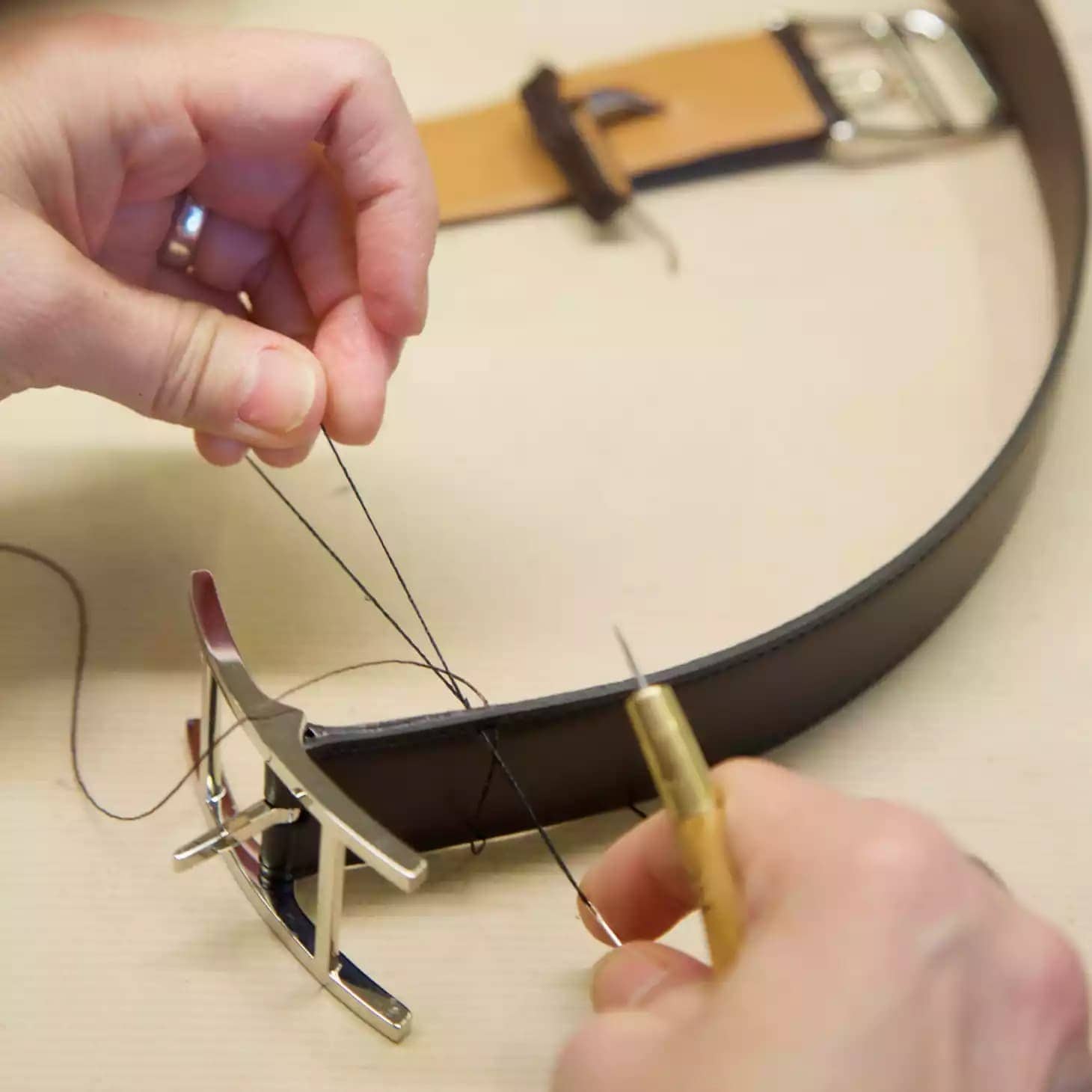

However, very few brands offer repair as part of the service. Those that do often sit in the leather goods or denim sector. Hermès, for instance, are known for their aftercare services, boasting the slogan “repaired objects are loved objects.” The atelier claims to receive around 100,000 requests per year, with some of the goods handled up to 100 years old – a testament not only to the houses’ quality – but to the long-term, customer engagement benefits of building repairability into a business strategy.

Founded in 2015, The Restory saw a gap in the market for consumers looking to revive said “loved objects.” Their revival services span footwear, accessories, handbags and clothing, with testimonials claiming items are returned as “good as new.”

“Knowing that I can wear these accessories almost to the point of no return highlights which pieces I want to invest in, as they can now be considered truly timeless,” says one customer. Proof in action that repairs equal greater long-term investment across the board. What started as an online service has seen such success that the brand now has in-house services at Selfridges, Harvey Nichols and Harrods, with services starting at £35.

However, circularity doesn’t have to come with a price tag. Part of the parcel to ensure sustainability is effective is to make it accessible to all. Throughout global lockdowns, handcrafts, home repairs and the DIY economy reaped the benefits of consumers being confined to their homes. While some cleared out wardrobes for resale and some uploaded their clothes to rent, others looked to revive their wardrobe from home.

Design duo Alicia Minnaard and Dave Hakkens saw the potential in this new wave of menders. In April 2021, they launched Fixing Fashion, a free, open-source platform dedicated to upskilling users on how to mend, upgrade and care for their clothes. Video tutorials cover everything from stain removal, sewing, patching, darning and care instructions, ensuring that techniques are accessible, using resources around the home. Also on offer are a range of re-design ideas, from spliced t-shirts to reconstructed shirting, with menders encouraged to share their ideas with the broader community using the hashtag #fixingfashion. For Minnard, Fixing Fashion comes down to reclaiming lost skills. “Repair’s nothing new; it was done before sewing machines ever existed. We forgot it because it’s easier to replace than repair. I think it’s a pretty big loss in culture.”

This obsolescence and lack of skills are an obstacle for the consumer who wants to minimize waste. However, for those who are more time-poor, and need a second pair of hands, app Sojo (dubbed ‘the Deliveroo’ of repairs) could be just the trick. Launched in the UK this January, Sojo connects the dots between the consumer and local seamsters, intending to close the loop on clothing that could otherwise end up in the bin. Just like ordering take-out, users can have their clothing collected via bike, dropped off at a local tailor, mended, altered and returned to their home in just a few days. Aside from keeping garments in the loop for longer, the app aims to help support local businesses, who may otherwise be left behind in the digital era. As for consumers, it brings a new life to clothes that you already love – and one that is greater – and more responsible- than buying something new.