Review of the The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s exhibit “About Time: Fashion and Duration”

Running October 29, 2020 to February 7, 2021

By Long Nguyen

Fashion is cyclical not just in the recycling of ideas from different eras and decades but also in the acts of refurbishing their respective physical garments.

We could not have imagined when we chose the name for this exhibition more than a year ago how apt the title would become after a six-month delay from the original May opening.

– Max Hollein, Director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

In a virtual conference Hollein expounded upon the late October opening of the annual Costume Institute exhibit ‘About Time: Fashion and Duration’ that offers an examination of fashion during the time from 1870 to the present. 1870 is the year the Met, now celebrating its 150 years, opened. “It offers a chance to reflect on how fashion, art, and culture can inspire and inform as well as make connections across cultures and time notions,” Hollein concluded.

Image | © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

This Costume Institute exhibition at the Met displays the process of fashion in the last century or more and distilled this process of creativity in fashion into a condense visualization – how a shape of clothes so deep-rooted in one era evolved as society advanced and as culture and taste transformed and how fashion designers borrowed these particular shapes for their own collections either celebrating or subverting the past, the near present and the present.

“As a designer, I have always looked to marry silhouettes, techniques, memories, and impressions from the past with the latest technology to create fashion for today that speaks to the future,” said Nicolas Ghequière, the women creative director at Louis Vuitton, the exhibition main sponsor with three outfits within the Gallery 999 on the second floor sandwiched between Modern and Contemporary Art and 19th Century European Paintings and Sculptures.

The pandemic has also created a certain space to reflect upon where we are and where we are going. And in the most turbulent times, heart, fashion, and culture can help navigate change and frame how we see the world anew.

– Nicolas Ghequière

Ghesquière also mentioned how critical the Costume Institute archive has been to his own work and his fondness for positing garments outside of their historical time and context into the present-day wardrobe.

Ghesquière described his Spring-Summer 2018 ‘time travel’ collection with the inspirations that he had found in the Met archives as his most memorable show for Louis Vuitton that took place inside the basement of the Louvre that contained the fragments of the original walls from the medieval era. A silk jacquard sleeveless long military vest and a pair of silk running short from this Spring 2018 show, a marriage of Napoleonic and ancien régime military garbs and formal 18th-century menswear and athletic wear, is on display in the first gallery next to a gold silk and metal thread floral motif embroidered black silk velvet appliqué riding jacket with silk satin ribbons and a white blouse with bow neck and puff sleeves and a long black skirt made by Morin Blossier in 1902 for Queen Alexandra, the consort of British King Edward VII, a style of jacket borrowed from 18th century France.

Image | © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

“The Met Costume Institute collection could be considered as a dense 150-year clock of the architecture of the female form, one and a half-century worth of garments each recording delicate calibrations shifts,” said Es Devlin, who designed the two separate galleries, one with a circle giant clock with a swinging pendulum and white markings around the floor and white painted the railings mimicking the separations of minute and second handles of an actual clock that separated each pair of outfits and the other completely covered in reflective glass from walls to ceilings to visualize the interconnectedness. “Interestingly, the parts of the female body that are subject to the wildest extremities of architectural expansion and contraction are those that relate most to childbearing – the bust, the hips, the stomach,” Devlin said how she envisioned the exhibition set in a way that the audience can experience the time dimension in how the exhibit itself is structured with the division into two parallel timelines and in two symbolic clocks one for each gallery.

In essence, the show is a meditation on fashion and temporality drawing out the tensions between change and endurance, ephemerality, and persistence. Recently time has dominated discussions within the fashion community, and these conversations have centered around the accelerated production, circulation, and consumption of fashion to meet the commercial demands of an interconnected and digitally synchronized world, but we realize that these demands are having a detrimental effect not only on the creativity but also on the environment.

– Andrew Bolton, Wendy Yu Curator in Charge of the Costume Institute

“The ensembles are culled mostly from the collection at the Met along with two parallel timelines, one featuring 60 ensembles arranged in chronological order from 1870 to the present. It focuses on the forward-moving and progress-oriented nature of fashion that’s governed by novelty, ephemerality, and obsolescence. The second timeline interspersed is a series of 60 interruptions that pre or post-date the first timeline but relate to them in terms of shape, motif, material, technique, or decoration. The 60 ensembles in each timeline are primarily in black to emphasize their changing silhouettes and interconnections. The exhibition has been designed as two enormous clocks with 60 illuminated tick marks that reference the number of minutes in an hour – each tick contained two ensembles the front object represents the linear, chronological timeline and the back object the non-linear timeline,” Bolton explained in detail the structure of the exhibition that when taken together both timelines expressed what the French philosopher Henri Bergson referred to time as a continuous flow between past and present and each pair of outfits is a union of past and present unbound by a sense of chronology.

The audience entering and traversing between the two galleries can experience the audible effects with a reading of excerpts from Virginia Wolf’s Orlando: A Biography (1928) by the actresses Nicole Kidman, Meryl Streep, and Julianne Moore. Segments of music from the movie The Hours 2002 ‘The Poet Acts’ and ‘Morning Passages’ by the composer Philip Glass are played in each of the two clock rooms.

The opening section of the Clock One gallery showed the most interesting development of voluminous shapes that started in the 1870s and evolved to the early twentieth century. Designers in the last half a century adopted and adapted these hourglass princess lines into a wardrobe for their own specific time. The time line showed how extensive the adapted past silhouette influenced indirect ways in the cuts and the drapes that resulted in familiar looks.

“Charles Frederick Worth introduced the princess line in 1876. The princess was basically a one-piece dress, and it was formed without a waist seam so vertical seams would continued from the shoulders through to the skirt, which created a very form fitted hourglass silhouette and typically, the princess line wasn’t worn with a bustle, but back interest was maintained through a series of puffs so Worth reintroduced the bustle in the early 1880s,” Bolton said of the black silk velvet trimmed with a dress with back skirt drapery of tiered black chenille fringes from 1885 paired with a similar black long overcoat with cutaway back revealing the nylon tulle poufs in lieu of an actual bustle by Yohji Yamamoto for his fall-winter 1986-87 collection. An Alexander McQueen ‘bumpster’ black silk faille skirt from his fall-winter 1995-96 Highland Rape collection was chosen to represent the similarity of the straight line in the back produced by the long-waist princess dress from an 1877 afternoon dress of black silk faille trimmed with silk satin – both the 1877 dress and the 1995 skirt created the illusion of an elongated torso that ended at the bottom of the spine.

McQueen borrowed the princess silhouette idea but executed his proper version with little physical resemblance from the past. This wasn’t always the case for other designers who borrowed for purpose – to enhance their own shapes or even destroy the ideal.

In the circular panoramic of the Clock One gallery displaying the chronology from 1870 to the mid-1950s, modern-day designers borrowed the shapes and structures of fashion at the turn of the century from the princess dress to the beginning of menswear influences in women’s clothes as inspirations in terms of creating silhouettes that are seemingly deemed as more expressions of design creativity rather than commercial fashion for the current crop of avant-garde designers.

Borrowers in later years can celebrate these silhouettes from the turn of the century or distort them in a way as to destroy the idea of an ideal form.

On one side, designers celebrated these old shapes by incorporating them into their collections to enhance the more minimalist contemporary fashion destined to a new audience. Fine examples of this process on display are the following pairs: the Jonathan Anderson for Loewe black lace with white border dress for spring 2020 took its structure from the 1927 ‘Koh.I.Noor’ silk taffeta embroidered with silver metal threads and paillettes evening dress; a black wool coat with gold button and puff sleeves by Jonathan Anderson for his Spring 2020 Nouveau Chic collection reprised the leg-o’-mutton sleeves of a black raincoat from 1895 giving the present-day coat a new view with the sleeves lengthened and the waist narrowed; or in Marc Jacobs reinterpretation of the high waistline and narrow proportions of a French-style dress from 1908 into a high-waist dress with a set of buttoning that recalled the rigid cuts of men’s military uniforms for his fall-winter 2011-12 for Louis Vuitton.

Meanwhile, Rei Kawakubo reexamined surrealistic the last century’s dress like the 1895 Mrs. Arnold satin dinner dress with it intricately folded sleeves with asymmetrical cuts and a disordered assembly of sleeves for the Comme des Garçons fall-winter 2004-05 and Junya Watanabe recreated S curve in profile shape in a black thick padded dress like a dress stuffed with down feathers that albeit in a slightly distorted way to emphasize the artificiality of the volume lines from early last century for his fall-winter 2004-05 collection using as a base a black two pieces mourning dress from circa 1903 with a corset to contort the torso and pelvis to exaggerate the line are examples of this process of subverting the original borrowed idea.

As some women entered the workforce but still in very limited roles at the turn of the twentieth century, the single princess dress surrendered to the more tailored daywear jacket and skirt-like one with round lapels from 1892 that is paired with a fall-winter 1989-90 jacket with the leg-o’-mutton shape from Martin Margiela second collection. But it wasn’t until Gabrielle Chanel that women fashion in that era saw the complete abandonment of the 19th-century influences in terms of shapes as she ushered in a new silhouette with an eye on making it easier for women to be more mobile. “Gabrielle Chanel’s little black dresses and it’s arguably the dress of the decade if not the dress of the century and typical of her modernist aesthetic. She combines both formality and informality and softness and severity,” Bolton spoke of Chanel’s 1927 black dress in wool jersey.

In the Clock Two second mirrored gallery, the timeline started from the mid 1950s to the present with a mixed casting of how designers working today borrowed from the last century as well as from each other in both subtle and overt manners. Here, designers would take ideas from another designer who did a specific theme collection then incorporated them into their own proper collections with little or often no attribution. Sometimes the borrowings were subtle, and at times, they were overt.

Image | © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

“The 1960s saw a reprise of the chemise idea from the 1920s. In this example by Rudi Gernreich (from fall-winter 1968-69) – the only decoration you see on the dress is the zipper, which starts on the back of the neck and spirals around the body to the hands similar to Charles James Taxi dress in the 1930s named for the modern women undressing in a taxi. This dress has a feel for speedy dressing or undressing. We paired it with a floor-length version by Azzedine Alaïa from (spring-summer haute couture) 2003. Again the sole decoration is a zipper spiraling around the body from the top of the bust through the hands. Alaïa began experimenting with the zippers in the 1980s. In this particular piece, he used the zipper like an integral seam to trace and to enhance the contour of the body,” Bolton said of the pair of Gernreich-Alaïa black zippered dresses.

At times though, the connection between the paired outfits is not exactly clear and visibly easy to discern in terms of shapes, use of materials, or even specific responses to cultural changes as reflected in how the clothes were made in that particular way and the way the idea was borrowed.

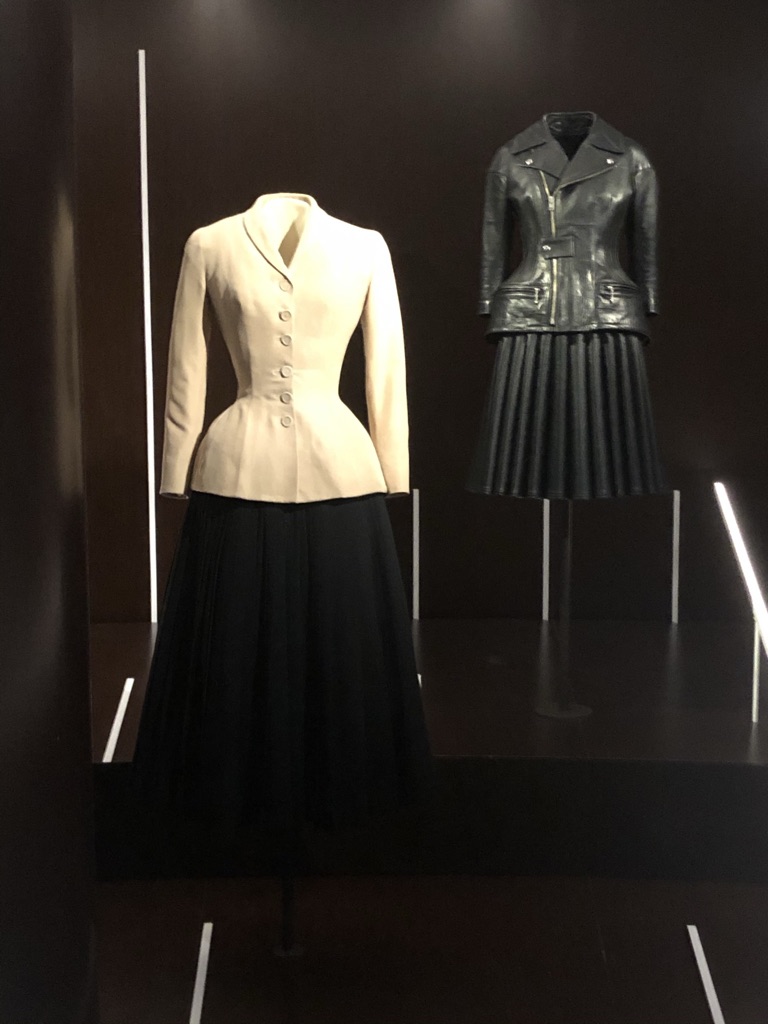

But there are also moments when the pairs of outfits resemble twins, albeit fraternal, not identical. For example, the pairing of the Gianni Versace spring-summer 1994 fitted long dress with boning and side cutaway held together by large golden safety pins in a nod to the punk era and the Zandra Rhodes Conceptual Chic fall-winter 1977-78 dress with embroidered nickel chain and brass safety pins; the 1947 New Look from Christian Dior here in a white fitted Bar jacket and flare long black skirt and the Junya Watanabe fall-winter 2011-12 black leather ‘Bar’ shape biker jacket and long skirt; or the black velvet corset strapless dress from Jean-Paul Gaultier fall-winter 1984 collection and a similar black ‘Tulip’ gown by Charles James from 1949.

The same can be said of the pair of a Halston fall-winter 1973 dress and the fall-winter 1996-97 Tom Ford for Gucci dress with a gold metal buckle on the cutaway hips side. Needless to say, there was a pair of Chanel tweed suits, a black with yellow trims tweed skirt suit by Karl Lagerfeld for spring-summer 1994 and a yellow tweed with black trims by Gabrielle Chanel for spring-summer haute couture 1963 – the same style but Lagerfeld made his skirt much shorter to fit into the ‘current language of fashion.’ These were garments cut from the same clothes, so to speak, albeit for a different audience as much as a crocodile mink trimmed coat and black skirt from Yves Saint Laurent for Dior fall-winter haute couture 1960-61 and a John Galliano for Maison Margiela for spring-summer 2020 more or less replicate a Yves Saint Laurent design but made with repurposing materials.

Image | © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Bolton pointed to the ways designers employed similar techniques working years apart, such as the Karl Lagerfeld embroidered trompe l’oeil custom jewelry on a black dress done by Lesage for his first Chanel haute couture spring 1983 and a Sarah Burton for Alexander McQueen sheath dress with embroidered crystal jewelry – “a hyperbolic interpretation of the Lagerfeld dress.” This can be said of the 1968 Paco Rabanne rhomboid, and silver metal dress and the Noir Kei Ninomiya synthetic leather and metal studs from his spring-summer 2015 collection – both designers employed unconventional materials and methods for their clothes.

Image | © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Bolton showed the similar visual style of a dress but made with a radically different methodology such as the 3D printed and laser cut plastic strapless corset dress with waves pattern skirt by Iris Van Herpen for her fall-winter 2015 collection and a yellow satin ball gown of the same silhouette from 1951 by Charles James.

“We end the exhibition with an haute couture dress from Viktor & Rolf (spring-summer 2020), which is a direct response to the temporal acceleration that has come to define fashion in the 21st century. Like many other designers, Viktor & Rolf have come to embrace conscious creativity and move towards slow fashion with this emphasis on value and quality, and longevity. Since 2015, their couture collections have been produced with fabrics from past collections, and for the spring 2020 collection, they created a series of patchwork dresses from their archive fabric swatches,” Bolton said about why he chose this dress to end with a note about the future of fashion that comprises of communities and collaborations to build sustainably like the patchwork laces on the dress. Well, the idea of sustainability is nice, but it’s such a hollow marketing excursion at this point than anything even slightly concrete that may lessen the pollution, the waste and the damage to the environment, and so forth.

Headpiece by Shay Ashual in collaboration with Yevgeny Koramblyum

Image | © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

What the exhibition does so convincingly and in such an academic and intellectual manner is that in fashion, originality is indeed a difficult concept to sustain in any meaningful and independent way as borrowing to enhance the current shapes of clothes or to destroy the idea of an ideal shape then and now has always been the currency of fashion.

Originality stems from using the specific ‘idea’ of a garment already made in a previous time frame and transforming older ideas into unique garments.

It was also surprising to see how so few American designers except Marc Jacobs, Rudi Gernreich, Charles James, and Halston have contributed to this ‘time’ fashion discourse.

As I left the preview, I saw a line of people waiting to get in, people not fashion people. For fashion experts and intellectuals, this exhibition cements the idea of a continuous flow of fashion ideas and silhouettes over time as a fashion garment depends on what came before. But what can these people wait in line eager to peek at the 150 years of fashion displayed in pairs inside Gallery 999? Can the idea of grand larceny or, in this case, ‘institutionalized grand larceny’ comes to their minds?

1902 Riding Jacket

Morin Blossier, French

Black silk velvet appliquéd with polychrome silk satin ribbons and embroidered with polychrome silk thread and gold silk-and-metal thread in floral motif

Gift of Miss Irene Lewisohn, 1937 (C.I.37.44.3a)

Nicolas Ghesquière for Louis Vuitton Spring/summer 2018

Louis Vuitton, French, founded 1854

Nicolas Ghesquière, French, born 1971

Gilet of polychrome silk jacquard in floral motif; shirt of white silk charmeuse; shorts of black synthetic plain weave shot with gold Lurex

Courtesy Collection Louis Vuitton

1895 Mrs. Arnold Dinner Dress Ca. 1895

Mrs. Arnold, American

Black silk satin trimmed with black silk net lace

Brooklyn Museum Costume Collection at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of the Brooklyn Museum, 2009

Gift of Sally Ingalls, 1932 (2009.300.643a, b)

2004 Comme des Garçcons Ensemble Autumn/winter 2004–5

Comme des Garçons, Japanese, founded 1969

Jacket of black cupra-silk satin and synthetic taffeta; top of black synthetic tulle; skirt of black wool-silk satin and white cotton muslin

Gift of Comme des Garçons, 2020

1918 American Red Cross Uniform

American, 1918

Blue wool twill appliquéd with Red Cross insignia and rank strips

Gift of Frances Townsend Fisher, 1994 (1994.352.1a, b)

2020 John Galliano for Maison Margiela

Spring/Summer 2020

Maison Margiela, French, founded 1988

John Galliano, British, born Gibraltar, 1960

Cape of navy wool broadcloth; shirt of blue cotton chambray; detachable sleeves of white cotton poplin; tabard of white synthetic organza; dress of blue wool twill and blue polyester charmeuse

Courtesy John Galliano for Maison Margiela

1947 Christian Dior ‘Bar’ Suit

Jacket: Spring/Summer 1947; Skirt: Spring/Summer 1947, edition 1969

Christian Dior, French, 1905–1957

Jacket of beige tussah silk; skirt of black wool plain weave

Jacket: Gift of Mrs. John Chambers Hughes, 1958 (C.I.58.34.30); Skirt: Gift of Christian Dior, 1969 (C.I.69.40)

2011 Junya Watanabe ensemble

Autumn/Winter 2011–12

Junya Watanabe, Japanese, born 1961

Jacket of black leather; skirt of black polyurethane

Courtesy Junya Watanabe Comme des Garçons

1994 Karl Lagerfeld for Chanel Suit

Spring/Summer 1994

Chanel, French, founded 1913

Karl Lagerfeld, French, born Germany, 1933–2019

Jacket and skirt of black wool tweed trimmed with white plastic; shirt of white cotton knit

Courtesy Collection du Patrimoine de CHANEL

1963 Gabrielle Chanel suit

Spring/summer 1963 haute couture

Gabrielle Chanel, French, 1883–1971

Jacket of ivory and navy wool bouclé; skirt of ivory wool bouclé trimmed with navy crepe de chine; blouse of navy satin-faced organza

Brooklyn Museum Costume Collection at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of the Brooklyn Museum, 2009; Gift of Jane Holzer, 1977 (2009.300.525a–e)

2012 Iris Van Herpen Dress

Autumn/Winter 2012–13 haute couture

Iris van Herpen, Dutch, born 1984

Black PVC

Gift of Iris van Herpen, in honor of Harold Koda, 2016 (2016.185)

1951 Charles James Ball Gown

1951 Charles James, American, born Great Britain, 1906–1978

Ivory silk satin

Brooklyn Museum Costume Collection at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of the Brooklyn Museum, 2009; Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Robert Coulson, 1964 (2009.300.1311)

Above 6 Photos Taken at Exhibit (Oct 26, 2020) | Long Nguyen