By Mark Hooper

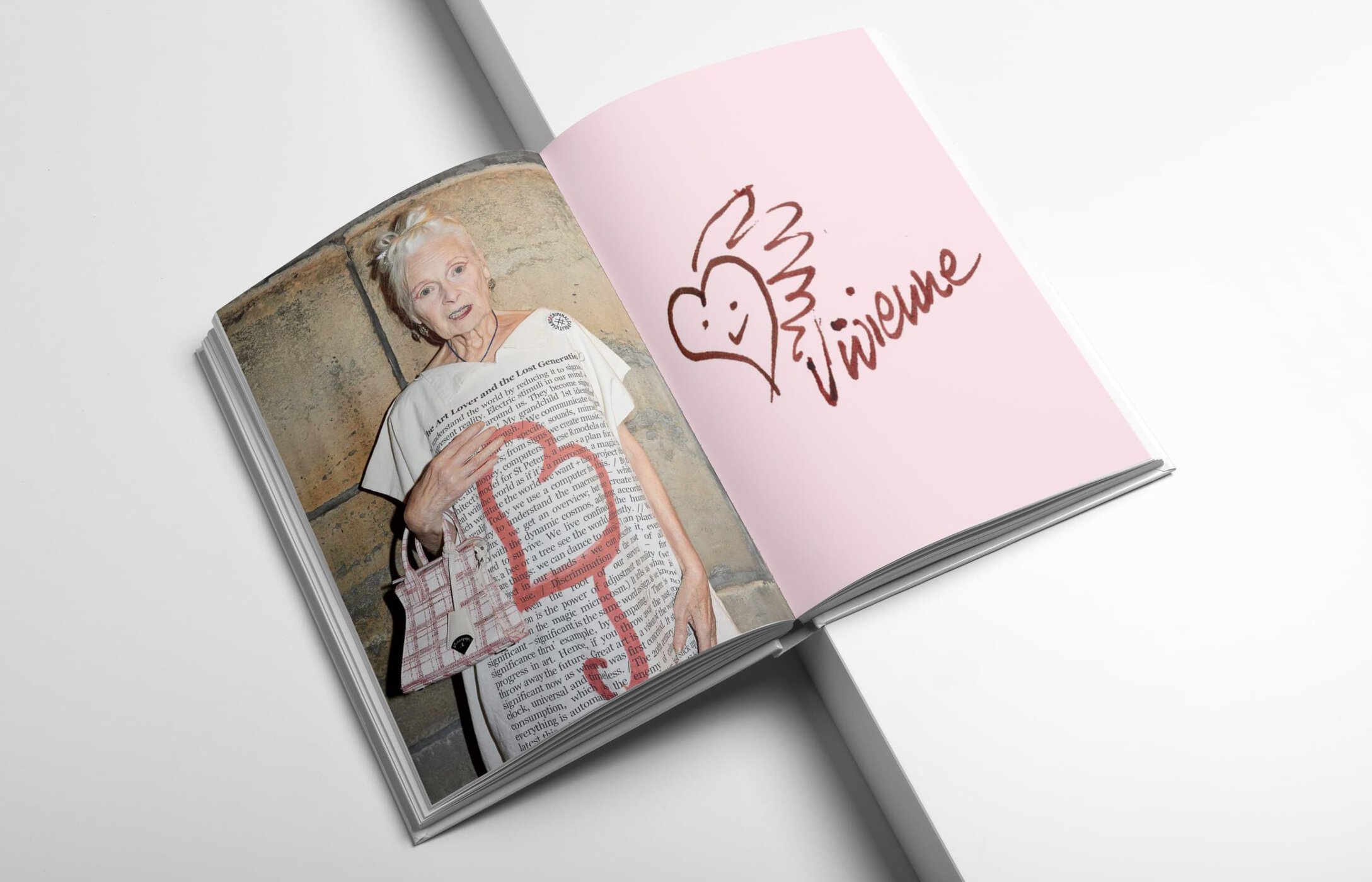

With the sad passing of Dame Vivienne Westwood shortly before the New Year, the fashion industry lost one of its most inspirational characters. But her legacy extends far beyond the clichés of punk, as Mark Hooper explores…

Takeaway: The Five Rules of ‘Westwood-ism’:

Question Authority, Fashion Is Political, Confront the Elephant in the Room, Defy Labels, & Demand The Impossible

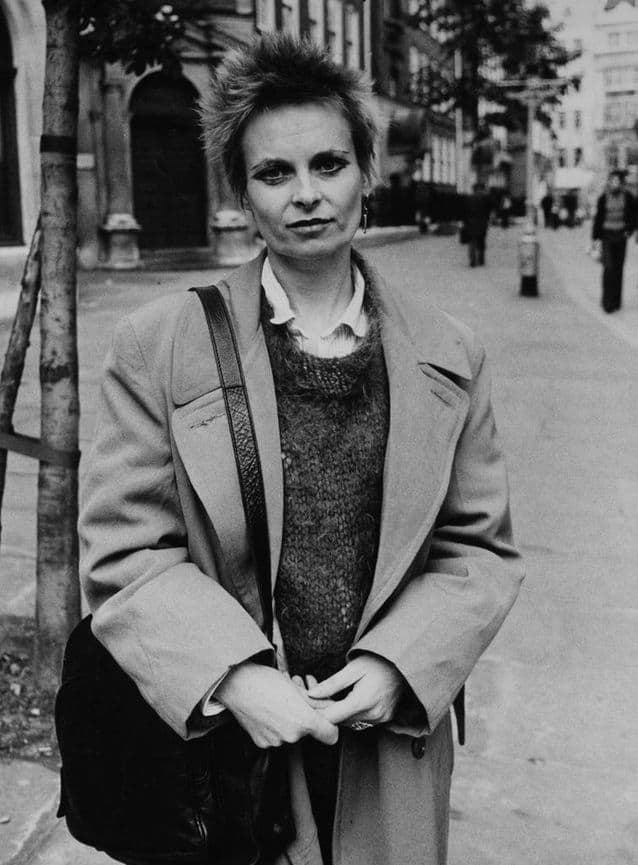

While there is no doubt the depth of feeling in the many heartfelt tributes to Dame Vivienne Westwood, who passed away on December 29 2022, aged 81, it’s important that her legacy isn’t lost behind SEO-friendly headlines. Yes, she can rightly be called an icon and an iconoclast. She was indeed the arch-outsider who became Britain’s Queen of Fashion, decorated and féted by the establishment. And of course you can’t talk about Vivienne Westwood without a generous sprinkling of the word ‘punk’.

But we shouldn’t lose sight of what a fascinating, nuanced, indefinable character she was – and it would be a disservice if we allowed her life to be neatly chronicled and appropriated by a fashion world that she had a complicated and often prickly relationship with.

She spoke witheringly about the ‘the drug of consumerism’ – whilst readily accepting the contradiction of her selling expensive clothes for a living. And it’s worth noting that this was the case at the start of her career, not just in her later years: the arch stylist Judy Blame (who passed away in 2018) once told me, ‘We couldn’t really afford Seditionaries clothes… so we would [go to] the jumble sale, buy a suit, throw a bucket of paint over it, cut it up, join it back together with safety pins.’

There is no doubt that she was one of the chief catalysts for punk. And one could argue that it was her vision (more even than her then partner Malcolm McLaren’s) that everyone else followed. But where that term has become shorthand for a particular style or look, Westwood applied the ever-questioning, subversive attitude of punk to everything in her life – simply because it was her attitude in the first place.

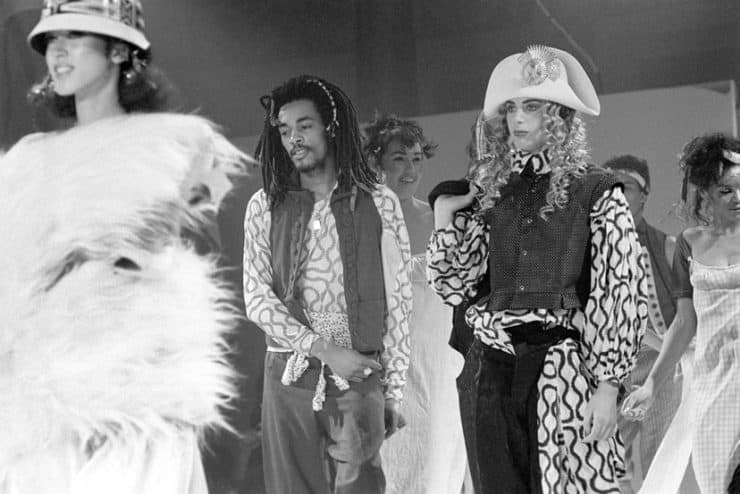

Her designs presaged, if not directly inspired, subsequent movements from New Romantic to Buffalo, and her influence can be seen everywhere in the history of post-war fashion, from Christian Lacroix’s distinctive puffball silhouette to the risk-taking that Alexander McQueen and John Galliano brought to Europe’s most respected fashion houses.

You could say that Westwood established a blueprint for all those British designers that came in her wake – one that demanded they be disruptive in challenging the mores and traditions of the industry, while fostering a full understanding of them.

It is the reason that British fashion can still hold its own today – and it is something that has never been more vital in the current homogenised, risk-averse climate.

Although she defied and transcended any label attributed to her, Vivienne Westwood was always knew the power of a good slogan. So here are five rules to live by, inspired by her considerable legacy:

Question Authority

The very ethos of punk was to push back at the men in suits who told you how and why you should act. But for Westwood, questioning meant more than punk cliché of spitting at authority: it was a deeply-held principle, an obligation to talk truth to power. Rather than nihilistic rejection, it was fuelled by a sense of natural justice and an understanding that you can use the establishment for your own ends. In terms of fashion and culture, it wasn’t all ‘Destroy’. She was well aware of her history, and knew full well that you need to understand the rules better than anyone in order to break them. (As Judy Blame put it: ‘We were nicking what we liked from the past and shoving it into the future.’)

What she posited in its place was an alternative history – with her as a modern-day Boadicea, laying waste to the vagaries of polite society. In this context, rebellion, revolt and disdain are at the very heart of modern democracy. When she talked of putting ‘a spoke in the system’, it was directly equivalent to the ‘good trouble’ that John Lewis advocated.

Fashion Is Political

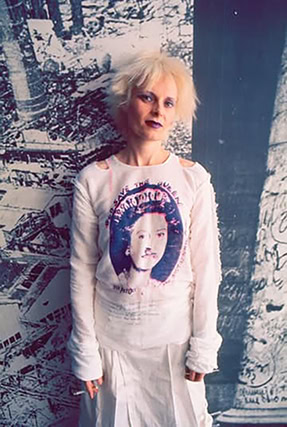

Having established her own manifesto, clothes became Westwood’s currency and her medium. At the height of punk, she renamed her shop on London’s King’s Road ‘Seditionaries’ where previously it had been ‘SEX’. (Sex sells and indeed shocks – but the new name revealed the method behind the apparent madness.)

We should never forget that clothes still carry this power. For all the sheen of consumerism we put on it, fashion still has the ability to provoke, question, confront – and affront.

Westwood was, by any definition, an activist to the last. Be it climate change, civil rights or sustainability, she was never afraid to point out the elephant in the room and make a nuisance of herself in doing so.

Confront the Elephant in the Room

Clothes are for everyone. And anything can be clothing. In the Julien Temple documentary The Filth and the Fury (2000), there is an important point about punk fashion that many have missed: the original punks didn’t wear leather jackets, for the simple reason that they couldn’t afford them. The reason they adopted ‘bin bag’ skirts was because, due to industrial strikes in the 1970s by refuse collectors, the streets were piled high with black bin bags (‘If they were going to call us trash anyway, we thought why not look like it?’)

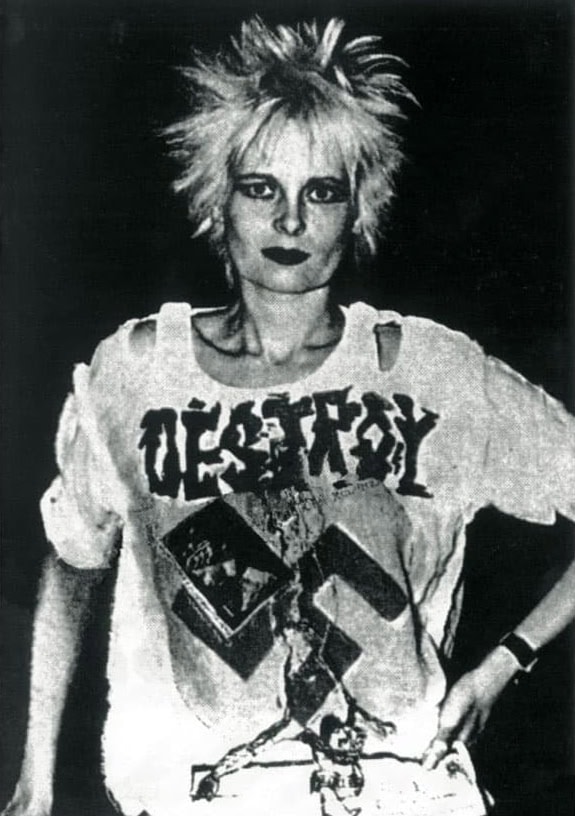

As it was Westwood’s policy to always confront the elephant in the room, it’s high time we addressed one topic that everyone else has tactfully avoided in their obituaries: the Nazi Issue. Westwood used the Nazi swastika in her early designs, and many punks appropriated the symbol in their homemade outfits. It’s important to be crystal clear here: punks (and Westwood) were defiantly anti-Fascist in their politics. (The DJ, musician and filmmaker Don Letts recalls once arguing with Bob Marley on this very issue, insisting that the punks he’d seen wandering the streets of London were on their side and stood against ‘The Man’.)

Westwood herself stated that her intention was to point out the hypocrisy of the establishment that punk had come to bury, and to accuse them all of being fascists. And to be fair, her most infamous red swastika design (for Seditionaries) was presented under the word ‘Destroy’.

But there’s no doubt that Westwood and McLaren also understood the power of the symbol to offend, since their main target was their parents’ generation, who had lived through the war (both were born in the 1940s). Their impulse was to shock – and they used everything at their disposal to do so. The problem with this is, of course, that without someone to explain your intent, you are left wearing a T-shirt bearing a deeply offensive symbol. Whatever their motivation, there is little doubt that today such subtleties would be dismissed.

Defy Labels

Despite her and McLaren’s love of defiant slogans, Westwood refused to have her life lazily summed up by one. As the photographer Nick Knight explained to me, ‘When punk first started it was about being individual and expressing yourself rather than falling into line with other trends. And I think that’s still really important today – probably even more so. Punk quickly became commodified and became a code of dressing, but when it first came out it was much more diverse and eclectic and creative. And that’s the aspect I’ve always loved – that ability to claim loudly that you exist and you’re different, rather than just being part of some marketing or social group.’

Judy Blame put it more bluntly: ‘You didn’t want to look like a gang. You’d drop dead if someone looked the same as you.’

Demand The Impossible

Westwood was uncompromising in her ideals and refused to be brow-beaten by anyone who claimed moral superiority over her. This applies as much to her climate activism as to her healthy disregard for the ruling classes. Her partner in life and work, Andreas Kronthaler, has vowed to continue her efforts in this area – not least through The Vivienne Foundation, the not-for-profit organization she conceived with family members in late 2022, and which will formally launch next year. The Foundations identifies four pillars – Climate Change, Stop War, Defend Human Rights and Protest Capitalism – that represent her legacy as both designer and activist.

To steal another of her famous slogans: ‘Be reasonable: demand the impossible’.