Exhibition Curator Hélène Starkman on Dior’s History of Hope, the Politics of Beauty, and the Art of Subversion

By Mackenzie Richard Zuckerman

Today, Jonathan Anderson takes his first official bow for Dior Men—and in doing so, quietly makes history. For the first time since Christian Dior himself, one creative director will oversee both the men’s and women’s collections, signaling a new era of cohesion at the house. But while fashion turns its attention to what’s ahead, a quieter and equally revealing chapter is unfolding in the Luberon Valley.

At SCAD Lacoste, the exhibition Christian Dior: Jardins Rêvés—curated by Hélène Starkman for Christian Dior Couture—offers more than just a picturesque view of the house’s past. It’s a meditation on Dior’s emotional and creative roots. Set within a dreamlike garden of hand-crafted blossoms, and framed by 78 years of design, it reflects the house’s enduring identity: one built on beauty as resistance, craft as collective memory, and history as a source of renewal.

Starkman, who has spent over a decade preserving and curating Dior’s heritage, offers a rare lens into the connective tissue of the house—what holds amid change. Her perspective is uniquely valuable right now, as the industry watches to see how Anderson will interpret the codes of Dior. In speaking with her, we glimpse not only what Dior has been, but what it continues to mean.

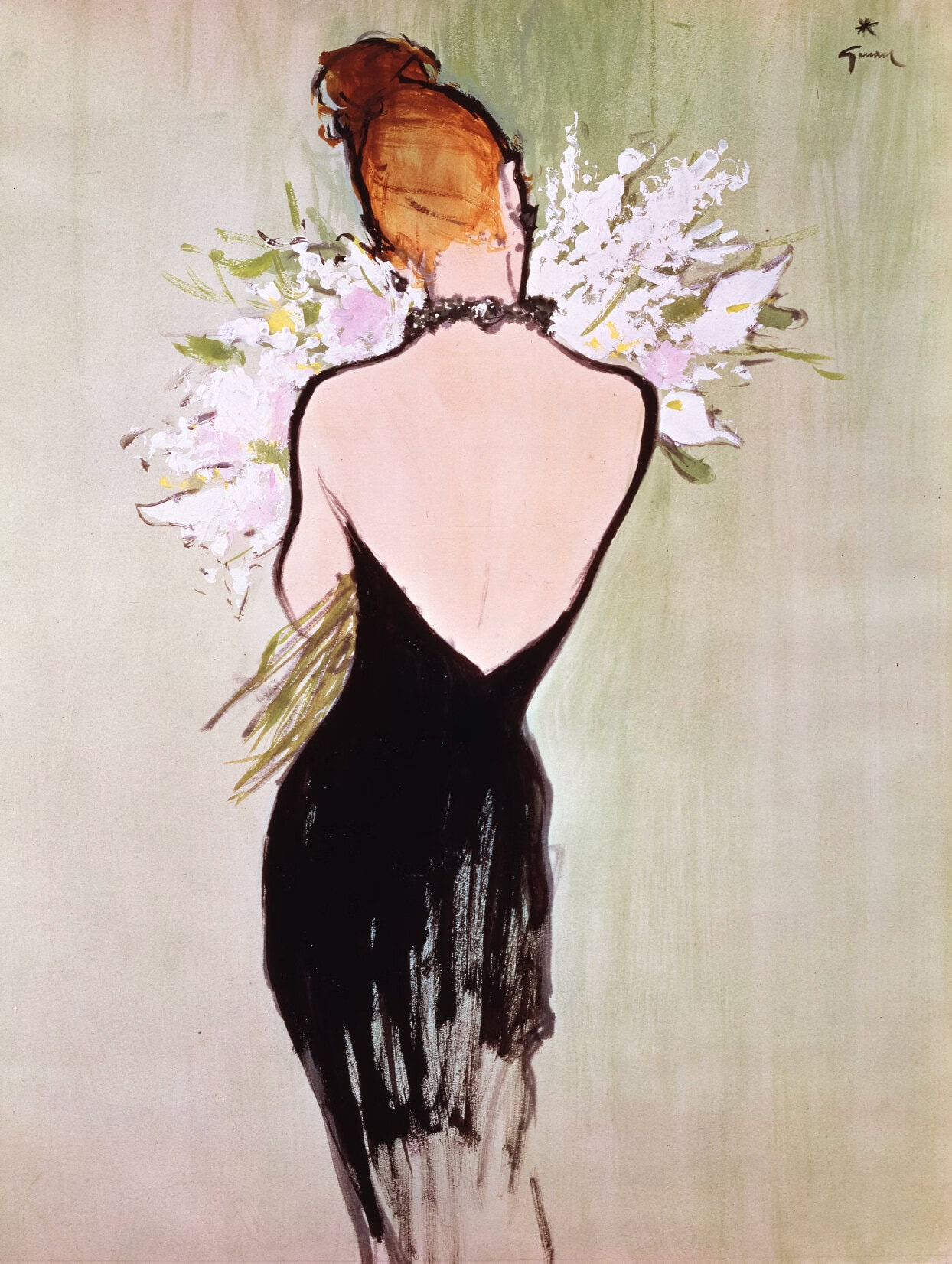

What emerges is a portrait of a house rooted in contrasts: romantic yet rigorous, forward-looking yet fiercely archival, consistent in ethos even as its aesthetics evolve. And at the center of it all—then and now—is the garden: a symbol of femininity, memory, and imagination, but also of quiet subversion. As Starkman reminds us, when Christian Dior launched his first collection in 1947, using fifty meters of fabric in a postwar world of rationing, it wasn’t just luxurious. It was radical.

“We call the exhibition Jardins Rêvés so people can dream,” Starkman explains. “This isn’t about selling a gown—it’s about stepping into a world of beauty, of imagination, a place outside the noise of everyday life.” The idea of the garden, for Dior, is not decorative—it’s foundational.

Christian Dior’s childhood at Villa Les Rhumbs in Normandy, where he gardened alongside his mother and sister, formed the emotional blueprint of his house. But that garden, Starkman reminds us, grew in the shadow of conflict.

“When Dior created his house in December 1946—just after the war—his sister Catherine had only recently survived the horrors of the concentration camps. The world was devastated. And he came forward with this vision of happiness, of femininity, of beauty. But it wasn’t frivolous—it was bold.”

Dior’s famed “New Look,” with its full skirts and extravagant fabric use, shocked many in a post-rationing era. “At the time, in America, there were fabric laws. You couldn’t have more than one inch of hem, or more than four buttons. And here comes Dior, using 50 meters of fabric. It was considered obscene,” Starkman recalls. “There were even protests—the ‘Little Below the Knee Club’ in Chicago. But that’s what made it powerful. He brought back luxury when people had only known scarcity. He offered a dream.”

This tension between history and hope, structure and softness, is echoed throughout Jardins Rêvés. The exhibition gathers floral- and garden-inspired garments by Dior and his successors—from Yves Saint Laurent and Marc Bohan to John Galliano, Raf Simons, and Maria Grazia Chiuri—set within a paper flower installation by scenographer Wanda Barcelona. Visitors move through a “fashion herbarium,” where garments converse across decades, revealing unexpected continuities.

The legacy, Starkman notes, isn’t just visual—it’s material. “When you see the dresses in person, you understand the three-dimensionality, the craftsmanship, the community behind them,” she says. “Some students visiting don’t even realize careers like embroidery or featherwork still exist. But they do. And Dior has always relied on these artisans.”

That behind-the-scenes labor forms its own quiet resistance—especially in an age of instant images and ephemeral trends. “It takes a village,” Starkman says. “It always has.”

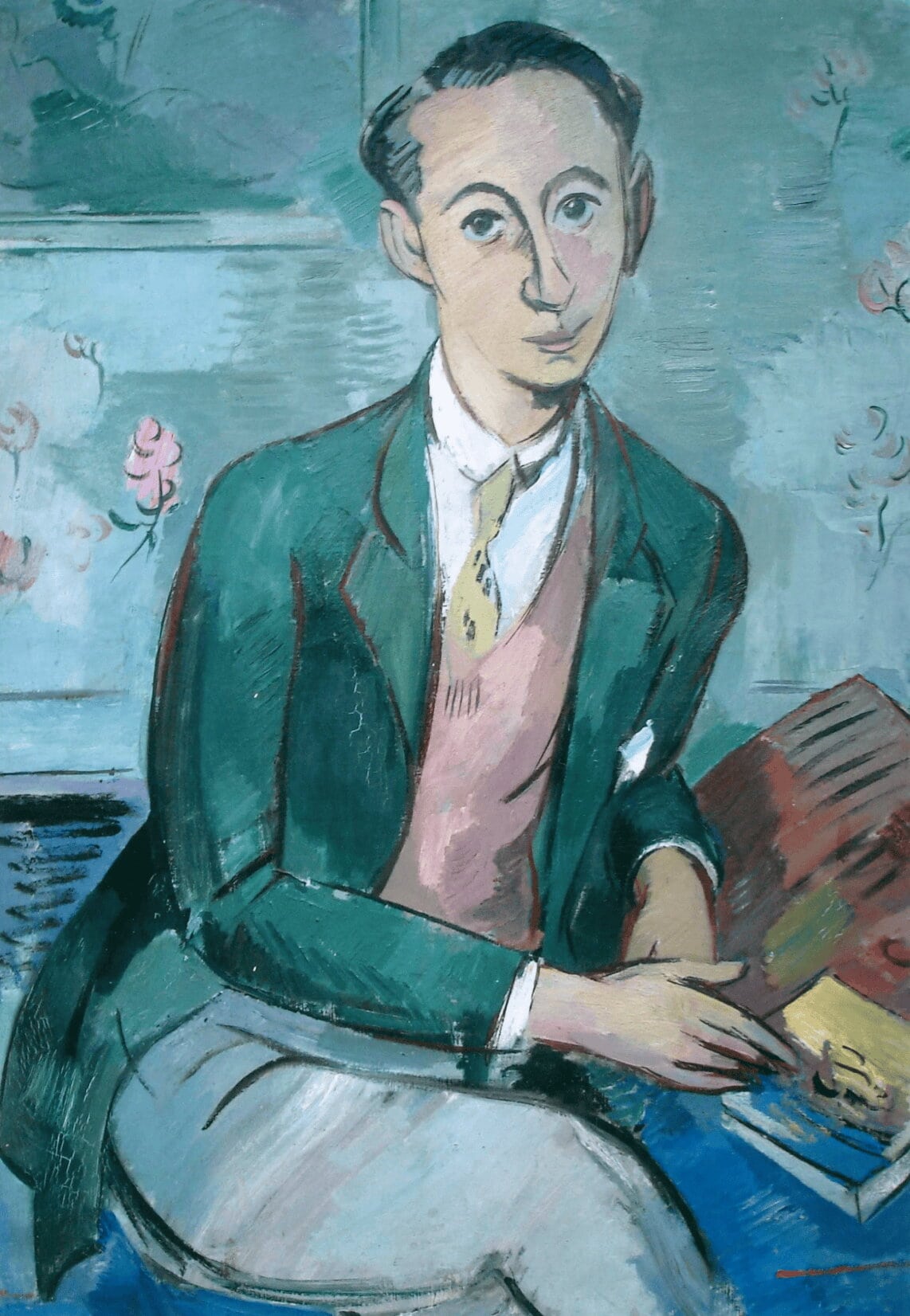

Each creative director left their mark through this garden framework. Saint Laurent, Dior’s young protégé, extended the house codes with grace. Bohan, who served nearly three decades, designed with the times—bold prints, sharp silhouettes—but maintained emotional ties to color and proportion. Gianfranco Ferré’s baroque grandeur echoed Dior’s architectural romanticism, while Galliano’s seemingly wild creations were often deeply rooted in the archive. “He was obsessed with research,” Starkman notes. “Even his most theatrical pieces trace back to a historic silhouette or an original fabric swatch.”

Raf Simons brought a modernist’s restraint. One early gown featured classic embroidery on the front and sculptural 3D florals on the back—two aesthetics in tension, or perhaps in harmony. “He wanted to show that you need the past to create the new,” she says.

For Maria Grazia Chiuri, the garden becomes personal and poetic—a site of reflection, feminism, and fragility. “She may be the closest to Dior himself,” Starkman suggests. “Romantic, yes, but also intellectually grounded. And it matters that it took seventy years for a woman to lead the house. Her vision adds something essential.”

Accessories—hats, shoes, jewelry—are granted rare prominence in the show. “On a runway, you might miss them entirely,” Starkman says. “But here, you can stop. Dior always envisioned a total silhouette. Even the smallest detail contributes to the whole.” That logic extends to scale: miniature dresses echo larger themes, reinforcing the idea that beauty exists at every size, and every level of attention.

Ultimately, Jardins Rêvés isn’t a retrospective. It’s a cultivation. The exhibition shows how Dior has evolved not by breaking from the past, but by blooming from it—season after season, director after director, always grounded in the same emotional soil.

There’s never been a designer at Dior who didn’t reference the archive,” Starkman reflects. “Some do it literally. Others emotionally. But the house is too strong not to engage with it.”

As a new chapter begins under Jonathan Anderson, Jardins Rêvés offers a quiet reminder: a garden is not just a symbol of beauty. It’s a metaphor for resilience, regeneration, and belief. At Dior, history doesn’t weigh down the present—it nourishes it.