Documenting the revolutionary genius of fashion

BY LONG NGUYEN

When “Martin Margiela: In his Own Words“, directed by Reiner Holzemer, opens on Amazon Prime and Apple TV this week, the film will join a host of documentaries and museums exhibitions in recent years on the work of the fashion designer Martin Margiela that include The Artist is Absent directed by Alison Chernick, 2015, the mammoth retrospective show Margiela/Galliera 1989-2009, Musée Galliera, Paris 2018, and Margiela, les années Hermès – Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Paris 2018; ModeMuseum, Antwerp, 2017.

Martin Margiela is indeed without a doubt one the most influential fashion designer of modern times – the period spanning the last decade of the twentieth and the first decade of the twenty-first century. His work centered primarily on fashion design and innovation from revealing the structure of garments to how to present the clothes.

With 41 shows in these two decades starting with the Spring-Summer 1989 show in October 1988 to the final show on September 29, 2008, for Spring-Summer 2009, Margiela achieved what elude so many fashion designers – his influences can be seen spanning across the spectrum of fashion today and in many ways not attributed to his work.

In this full-length documentary, Margiela is the star whose words and hand gestures guide the audience through the various phases of his life and work in an unprecedented personal manner, showing the audience drawings and items stored in white boxes and performing his design process on mannequins while explaining the various highlights of his collection showings. This film is a must-see even for non-fashion enthusiasts.

“He is in the top ten fashion designers all the way back to the nineteenth century for sure,” Cathy Horyn, the former fashion critic of The New York Times, concurred.

I had to work under the condition that Martin Margiela would remain anonymous. I quickly stopped missing his face in the frame of the camera. His hands, his movements, the admiration he has for handcraft, and, most of all, the love he puts in all his creations make us feel his presence at any moment. Irony and humor are persistently present in both his person and his work.

– Reiner Holzemer, Director “Martin Margiela: In his Own Words“

At the start of the film and throughout, one can see Margiela’s hand roaming through the white boxes containing different facets of his archives from his days at the Academy in a box titled ‘Academie Anvers’ to a box labeled ‘Souvenirs/Dessins/Illustrations Jean-Paul Gaultier 1984-1987’ from the preserved decoration of his design studio.

“Martin’s wish to explain and illustrate the philosophy and development of his work, to speak for himself after all those years was real. The challenge of getting close to a man who always prioritizes to make his art public than his person,” the director added about how the film provides this rare personal narrative of the process of creation at the heart of the Margiela fashion and aesthetics.

The Belgian designer was a giant in fashion because he challenged fashion from a design perspective, worked mainly to alter how fashion was made, and consume and created a new poetic sartorial vocabulary that resisted the obsessions of a logo and label-conscious era. Now, it may be a prime moment to hear the designer talk about the profound ideas that innovated and changed fashion and how we see clothes.

I don’t always want to comment on my collections. We had to create something new which was always difficult. I pushed myself constantly into extremes because I love discovering. And in fashion everything is quick. You are quickly famous and then quickly forgotten.

– Martin Margiela

Born in 1957 in Leuven, Belgium to a Polish hairdresser father and a Belgian mother, Margiela grew up in Genk, a small town about an hour east of Brussels. He remembered being at his father barbershop and witnessing the procedures of hair cutting and the additions of women’s wigs as a side business. “A fashion designer in Paris that’s what I want to be,” he told his mom after seeing a Courrèges fashion presentation on local television. Fascinated with the flat white cut off toes boots, Margiela would then cut off all the shoes of his Barbie dolls. But the fashion in his blood probably came from his grandmother who was a dressmaker that he observed her work closely and reproduced sketches with leftover fabric swatches in his notebooks. He even asked his grandmother to reproduced a 1966 white cut out Pierre Cardin dress for one of his dolls. It was not until the late 1970’s that Margiela first made a garment on his own – a miniature grey wool flannel double-breasted jacket skirt suit that he had seen from Yves Saint Laurent.

Margiela attended the St.Lucas Art School and Hasselt before going on to the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Antwerp where he graduated in 1980. At school, he mentioned one project using a drawing from history to construct a present-day garment and he chose a kitchen washing cloth to create a prototype jacket which was the original idea for the do-it-yourself (DIY) sock sweater for fall-winter 1991-1992 collection or the broken plate vest from fall-winter 1989-1990 or the plastic grocery bag corset top from spring-summer 1990. His big break came when he became Jean-Paul Gaultier’s assistant in 1984 where he saw the freedom that Gaultier espoused in his work.

“Do with what you have, and what you don’t have, you fake it, but do it,” he said about what he learnt at JPG. Gaultier further advised him that he could do something with his particular taste and style, giving a greater impetus to strike out on his own.

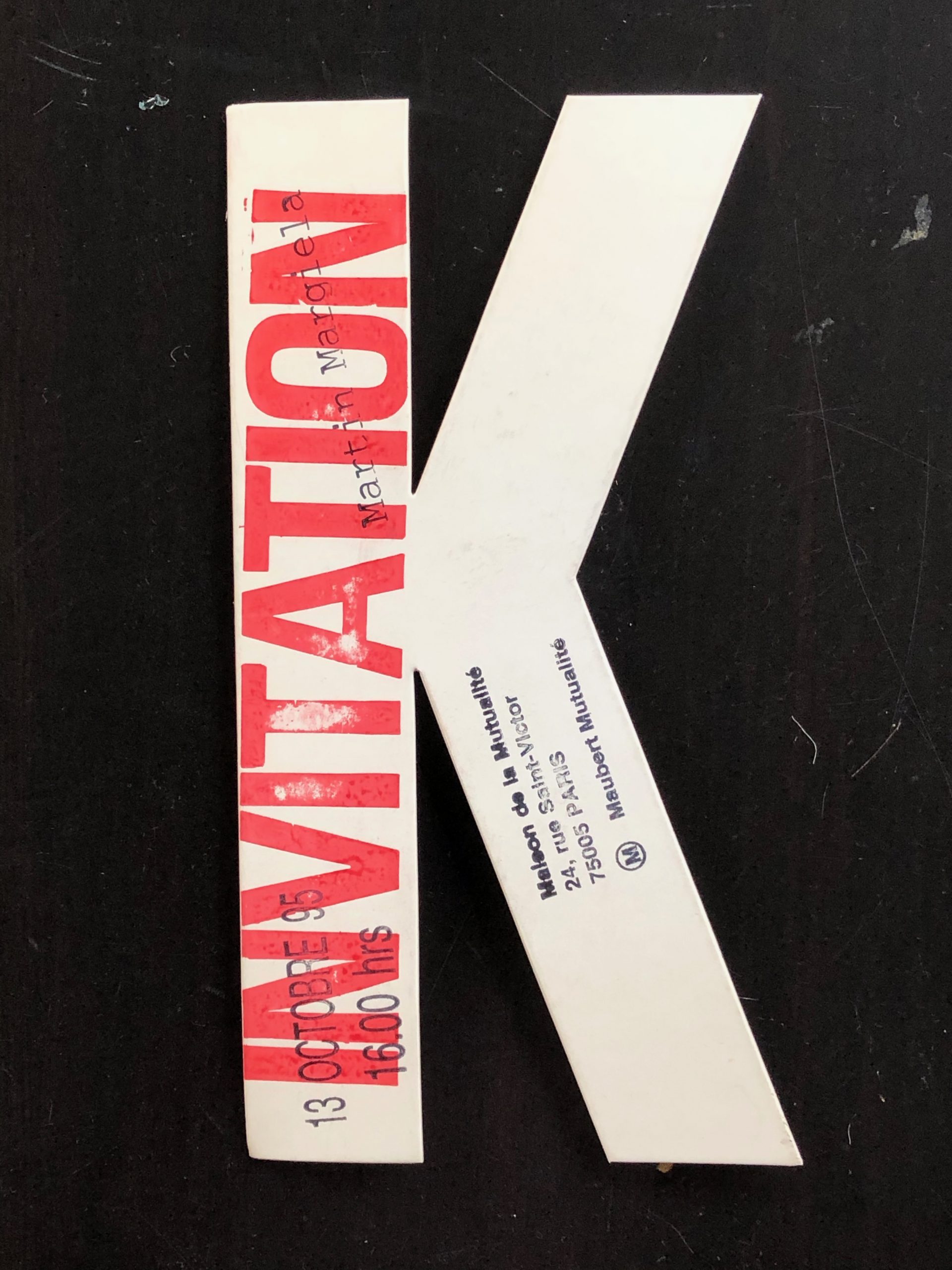

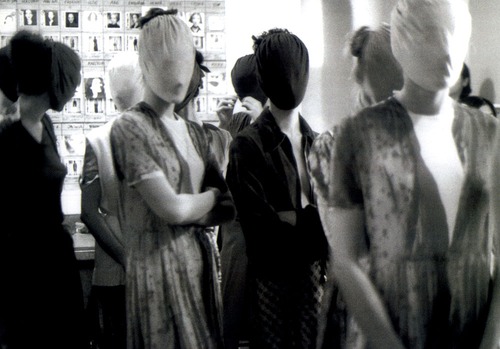

After leaving Gaultier in late 1987, the designer spent nearly a year with a business partner Jenny Meirens to launch Neuf Sarl, and to prepare for the official launch of the house on October 23, 1988, with the Spring-Summer 1989 collection shown at the Café de la Gare in the Marais. The show veered on the borderline performance art rather than the conventional high gloss shows taking place across Paris at the time. A telegram was sent as the invitation. The girls who wore the fifty-two looks in a range of white, red, and then black outfits made from contrasting materials and a finale of all simple white lab coats were friends of the house rather than famous top models prevalent on other runway shows. Chiffon or sheer nylon veils covered some of the models’ faces so audiences can focus solely on the clothes. Some were barefooted and others wore the cylindrical leather Tabi boots based on Japanese socks. The soundtrack was just a mixture of rock tunes from the Rolling Stones, Iggy Pop, or the Velvet Underground’s “Guess I’m Falling in Love.”

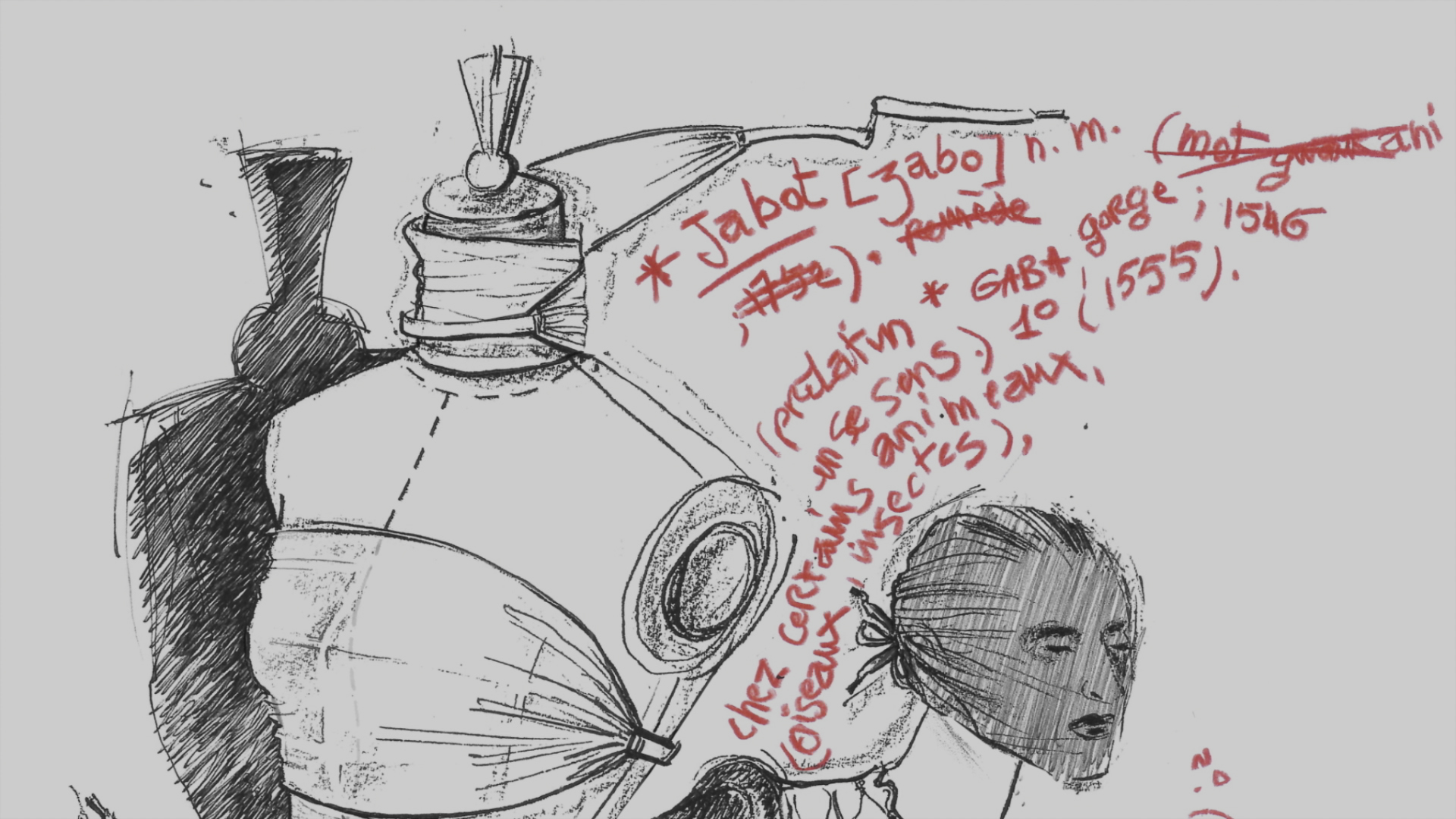

“We did what you call street casting, with heavy makeup,” Margiela recalled. “My first theme was a surrealistic eye in the atelier of Haute Couture. My love of historical fashion and accessories brought me to an accessory which is called the jabot that led me to the tiny shoulder pads of my first jacket, (veste #1)” Margiela explained his first jacket made for his debut show for Spring-Summer 1989 in October 1988 in Paris as a surrealistic eye view of a combination of his attachments to the historical fashion and the jabot which is a decorative clothing accessory falling from the neck. The abridged shoulder simply gave the neckline greater prominence and focus.

In the show, the model girls walked with shoes dipped in red paint on white cotton sheets leaving the red marks on the sheets that became the fabrics for vests with packing tapes closures in the following fall-winter 1989-1990 season – a precursor to the idea of upcycling and recycling but way ahead of its time.

It is a rare phenomenon that a designer’s debut show would contain so much of the seeds that would germinate into the major intersections of his work at the crossroad of a fashion system moving in the opposite direction. Margiela established immediately his ethos, his meticulous approach to the physical garment, and his methodology to dissecting actual clothes and creating new ones rather than fathoming a collection of clothes around specific inspirations like a voyage or an exotic country, themes that had little to do with fashion creation. This round shoulder silhouette was so contrary to the late 80’s norms of glamorous broad shoulder forms that dominated fashion at the time.

The seemingly imperfect fabrics and the intentional mixtures of different types of materials added to the act of rebellion against the artifices of consumption in the late ’80s and ’90s. The cotton jabot from an 18th-century picture was remade in exact reproduction into cotton bracelets and necklaces, a precursor for recycling processes not only of materials (the white cotton sheets splattered with red paint used as runway carpet was used to make vests for the next season) but of remaking the actual old and found garments themselves (like the separate Replica collection launched for Fall/Winter 1994).

The clothes from this first show, old and new, de-constructed and re-constructed, were the springboard for all of Margiela’s later work in exploring with greater depth how clothes are actually made. Here was the genesis of many of the Margiela ideas that had profoundly challenged and transformed all facets of fashion in a similar way to the advent to ready to wear in Paris in the early 1960s that eclipsed the allure of haute couture. In a way, he can be seen as a traditional fashion designer in the sense that he understood how clothes are made and the fashion system surrounding the marketing of clothes and raises serious questions about them both.

“When I first try a veil on a model in an outfit, something happened. There was no face, just the garment and then the movements of the garments,” he said. “For me in the silhouette, the most important details are the shoulders and the shoes. The shoulder gives you a certain attitude and the shoes, of course, give you certain movements,” Margiela explained the process of creating the Tabi shoes that he saw on workers during a visit to Tokyo but made them with high heels.

For Margiela, fashion ideas as well as each item of clothing contained an element of history. The idea for one garment can be developed into another garment as part of a process of evolution. He gave a second life to clothes and re-employed vintage clothes by tailoring them into new versions, playing with proportions, showing the intricacies of construction on the surfaces, or reversing the role of soft inner linings as the fabric of dresses. The tattooed print tank from Spring-Summer 1989 spawned an entire collection for Spring-Summer 1996 where photographic trompe d’oeil print of dresses with sequins, stripes, and knits that created a faux impression of what the actual garment actually was from its visual representation of simple garments that looked complicated.

The Stockman collection for Spring-Summer 1997 was the first major work on deconstruction and reconstruction and this principle continued into Fall-Winter 1997-1998 and Spring 1999 where heavy linen toile became the fabric of actual clothes rather than just mock-ups and where the designer dissect and reconstruct clothes with irregular hemline and frayed finishes like the nylon liners as dresses from Fall-Winter 1990-1991. “I was looking at the working of an haute couture collection and decide to use the unfinished process and studies as garments,” Margiela said of the Stockman collection.

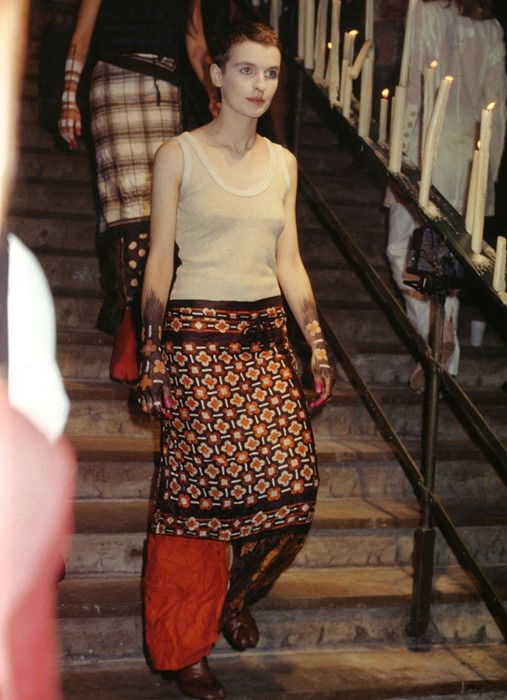

Sustainability was not a fashion word then but the broken ceramics plates assembled into a vest for Fall-Winter 1989-1990 affirmed the notion of recycling and of reusing and transforming garments into new clothes. The entire Spring-Summer 1992 collection expanded on the idea of re-usage of materials as the garments were made from vintage square scarves and other pieces of tapestry as models with painted limbs walked inside a close subway station on rue Saint Martin with candles along the steel railings for Fall-Winter 1989-1990.

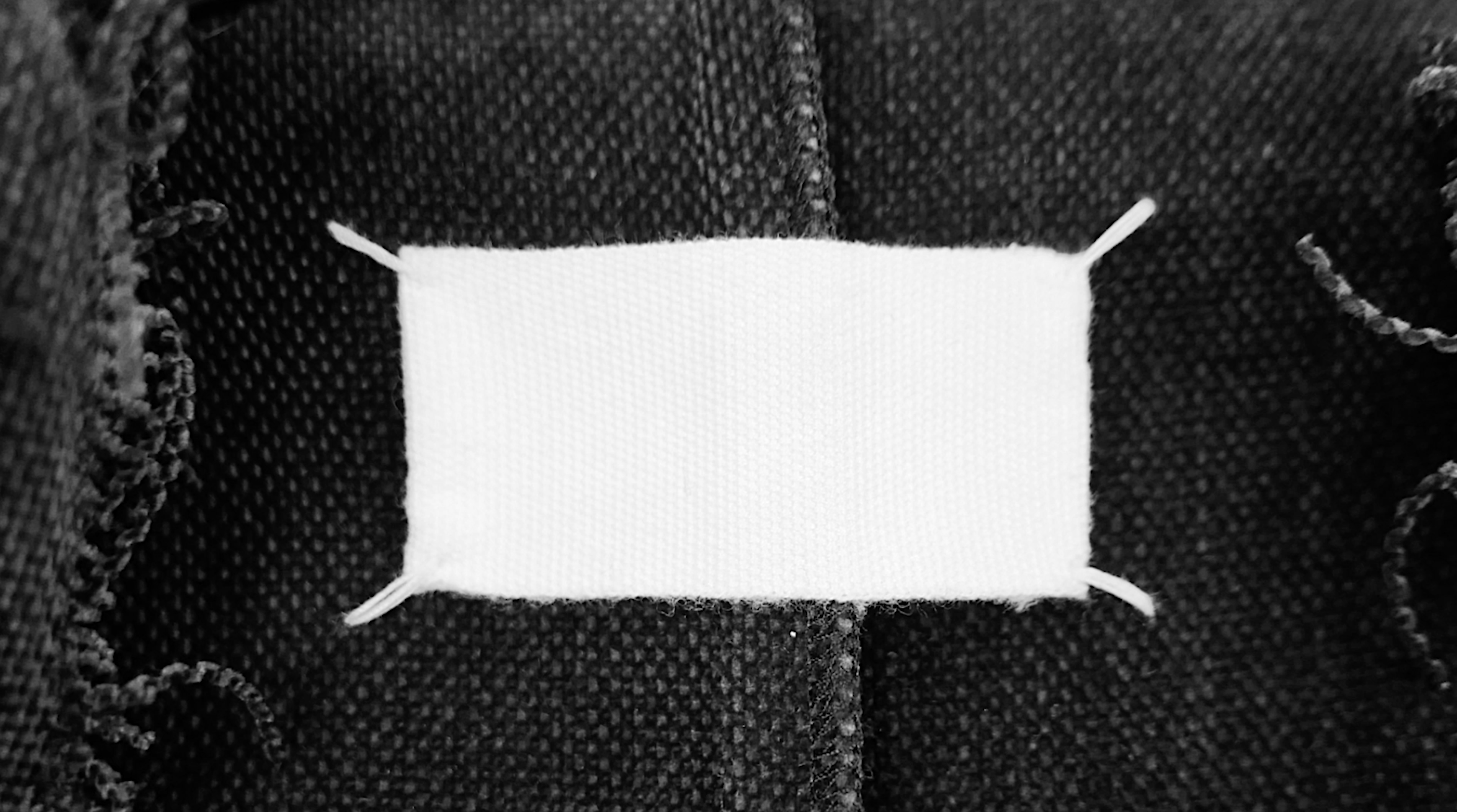

“ ‘I have seen this, I have seen that’ people keep saying. So we stamped on the clothes a label for Spring-Summer 1994 with the base where the actual garments were first made in red to specify the exact season. The focus was always on the garments themselves,” he said about the launch of the replica show of clothes in 1994 from various collections over-dyed in grey. “We came from a period where customers would go to a shop and look at the labels inside and said this is his or her. I don’t really like that idea. It took years before this white cotton label with four stitches would be named Maison Martin Margiela,” he said as he used clear duct tape to drape a plastic dry-cleaning bag on a mannequin into a ‘dress’.

Margiela opened a small box containing a doll he had clothed. His first experiment with the size and proportion of clothing came in the Spring-Summer 1990 show where he enlarged a cotton tank top over 200% to become a sheath dress or a white gauze a tank shirt squeezed unevenly underneath a sheer nylon fitted short sleeve tee shirt showing the extra fabric of the tank draping around the body. The exploration of proportions continued with the ‘doll’ collection for Fall-Winter 1994 where the actual dolls’ clothes were resized to fit a human adult albeit with the outsize large zippers, buttons, and buttonholes keeping in the proportion of the resizing process of 5.2 times the actual doll clothes sizes. “Doll garments on a living person.”

Oversized denim skirts, big sweatshirts, and large pants made their debut for Fall-Winter 1996-1997 and large duffle coats appeared in Fall-Winter 1999. But the most striking oversized collection was the XXXXL collection for Spring-Summer 2000 at the Jean Bouin stadium where each garment shown – molded to Italian size 78 on dress forms – was so massive and so contrarian to the skinny silhouette dominating fashion at the time. The term ‘Oversize’ rose from the underground that went on to greatly affect the hip-hop style of the early aught and recently made a comeback. The Spring-Summer 2000 XXXXL silhouette should be seen in the same light and influence as Christian Dior’s 1947 New Look in terms of proposing a novel and groundbreaking proportion.

Showing at the Café de la Gare wasn’t an aberration in the choices of location for shows but rather these out of the way and seemingly odd places like SNCF railway station, an abandoned subway, a hospital, an underground disco, public courtyards, restaurants, a concert hall, a theater, a supermarket, a circus tent, or even parking lots were the perfect setting outside of the norms for fashion shows at the time in Paris inside the Louvre Carousel. This too was central to the designer’s aesthetics creating the environment where these fashion ideas are created and nurtured. The film contains many cuts of the fashion shows taking place at all these unconventional locations.

In launching the men’s line 10, Margiela said the clothes were meant to be wardrobe staples, like opening a man’s closets and finding different jackets, pants, and shirts, etc. As in the women models in his shows, the male models were cast for their look and personality, not for their fashion popularity.

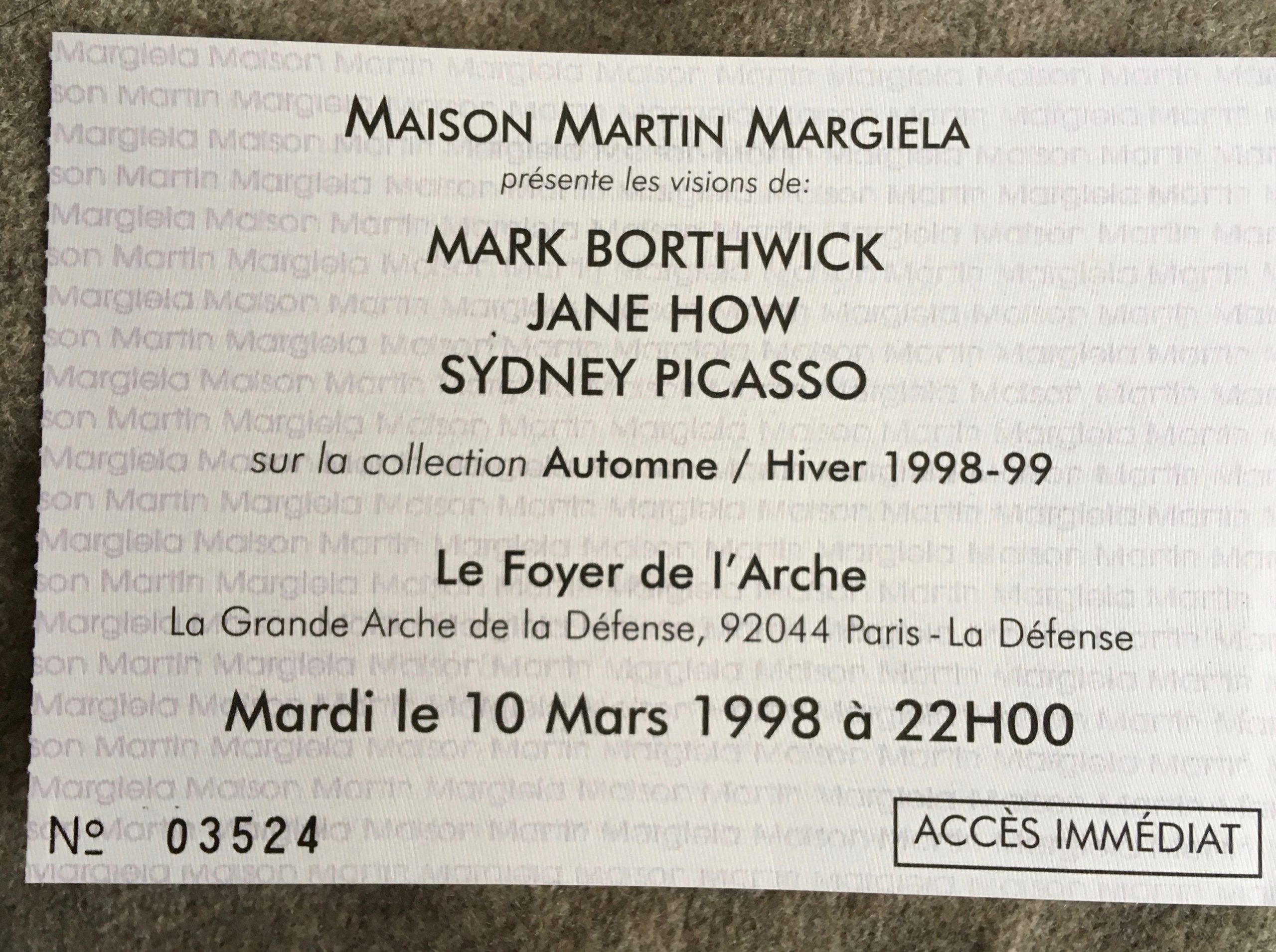

“Luxury is the perfect balance between quality and comfort and timelessness. People didn’t get that then,” Margiela said of the reactions to his first show for Hermès for Fall-Winter 1998-1999 show at the Faubourg store. Critic at the time dismissed his simple take on luxury with clothes so well cut and made with the best fabrics, but with his 12 collections, he managed to set the template for Hermès in a way that his creations seemed to have always been the Hermès style.

At the invitation of the French Federation, Masin Margiela’s couture collection, Artisanal, showed during the haute couture season beginning in 2006, elevating his collection made from refurbished found items into couture.

My first experience of Margiela was the Spring-Summer 1992 show inside a closed Saint-Martin subway stop in Paris where candle lights replaced runway lighting. The clothes were a vignette of vintage scarves and other found fabrics repurposed.

Two years later, on September 7, 1994, in New York City, the Charivari 57 store hosted the last of a multi-city live unveiling of the Fall-Winter 1994 collection, held at nine stores around the world including Tokyo, Milano, London, Bonn, and Paris. Mr. Margiela was present at the Charivari 57 presentation, according to sources.

Just after 7PM non professional models wearing ‘replica’ clothes tore the white paper that covered the store window on West 57th Street and ushered a cocktail party as well as the immediate availability of the merchandise worn by the models on the sales floor. At the same time there was a special tee-shirt made to gather funds for AIDS research. This was about a quarter of a century before the ‘see now, buy now’ become the rage in fashion retailing.

So memorable too was the Spring-Summer 1998 joint show with Comme des Garçons at the Conciergerie in October 1997 as an ode to the process of creation in the same manner as the marionette show six months later. After 10 PM inside the vast Conciergerie, men in white lab coats held in their hand completely flat clothes on regular hangers. Likewise, the XXXXL show under the white spotlight at the stadium on the edge of Paris and the ‘streetwear’ as high fashion for Fall-Winter 2000-2001 shown under the Alexander III bridge. And of course, the final show in September 2008, a twenty-year retrospective, where for the first time there was a note on our seats that said – ‘Twenty years, forty shows, hundreds of garments, what is there left?”

In 2002, Margiela took on an investor OTB group with the idea of expanding on several business fronts. But the arrival of OTB came with a new vocabulary like ‘marketing’ and ‘merchandising,’ concepts that were not until then prime directives for the designer. “In the end I became an artistic director in my own company. And that bothers me because I am a fashion designer and a fashion designer who creates and I am not just a creative director who directs his assistants,” Margiela recounted the process of change that was taking hold at the company. His long time first assistant Nina Nistche recounted how an invitation to lunch was the way Margiela informed her of his pending departure.

Margiela left his fashion house on the night of the 20th Year show – the 41st collection shown on September 29, 2008, at Le Cent Quartre in northern Paris. “I still regret that I had to leave the night of our 20th-year show and I never say goodbye to my team who gave everything,” he said as he wrote ‘Thanks to everyone who helped to make my dream come true!’ on a white cardboard paper. “The oversize tee shirts that became the wet look in the Spring-Summer 1990 show (including garments underneath plastics dry cleaning) is the most magical show of my whole career,” he said as clips showing neighborhood kids joining in with the models’ procession.

“It’s not about morals. It’s about creativity. That’s why he stopped which is extraordinarily brave for him given his love for clothing design,” said Jean Paul Gaultier.

“Margiela was the last revolution we had in fashion,” Carla Sozzani, the creator of the first concept store of its kind Corso Como, said at the start of the film. Since Margiela, there has not been any kind of conceptual fashion present in the scene and consumers have not been exposed to innovative fashion ideas in the last decade. Margiela provided the springboard for so many of the crucial ingredients of fashion now – upcycling, sustainability, and diversity among them. And no one gave Margiela the credit for the shredded denim jeans (Spring-Summer 2008), a rage that is still worn today.

Discussing today’s fast pace in fashion”

There was something very unpleasant in the fashion system. For me, it’s started when I had to go to the Internet on the same day as our show. I liked the energy that comes with a surprise and now everything was immediately pushed out on the Internet and I felt a little bit lost. This is the start where there is a different need in fashion and I am not sure I can feed that.

– Martin Margiela

Although every working fashion designer has more or less borrowed or plundered from Margiela’s repertoire, there is just one of his well-known heritage that so far no one has virtually duplicate in any way – his anonymity. “Anonymity is important to me. It balances me that I am like everybody else. I wanted to link my name to the products I made and not the face I have,” Margiela said while playing with a champagne corkscrew that becomes a necklace posed on a mannequin.

“Do you think you have told everything in fashion?” someone asked at the end of the film.

“No.”