INSIGHTS

By Long Nguyen

“The truth is that everyone is bored and devotes himself to cultivating habits. Our citizens work hard, but solely the object of getting rich. Their chief interest is commerce, and their chief aim in life is, as they call it, ‘doing business,” the 1957 Nobel Literature Prize French author and philosopher Albert Camus wrote in his 1947 novel La Peste. The narrative chronicle is set in the Algerian city of Oran suffering a bubonic plague epidemic in the 1940s and an allegory of the human condition’s absurdity.

“Orders! … When what’s needed is imagination,” said Jean Tarrou, one of the novel’s principal characters – a lonesome traveler who arrived in the city just before the plague hit and a keen observer of the daily life of its citizens – often as the voice of the author. In Chapter 8 of Part 1, decrying his utter disdain for how the government reacted to alleviate the plague’s crisis in bureaucratic manners instead of thinking of different solutions to solve the problem at hand.

The new Fall 2021 season shows will be here soon; the year 2021 is now, but even this New Year still feels much like it was in 2020.

At the end of the year 2020, the apocalypse averted, but deep wounds and scars will remain to alter the fashion industry’s long-term prospect, upending its structures and platforms.

Before the men’s fall and haute couture spring show in less than a fortnight away, let’s reflect on the year that the fashion year 2020 was unlike in any other fashion years. Despite this seemingly routine calendar schedule like the arrival of the seasons at a particular time frame, fashion has traversed the usual territory for so long it has suddenly morphed into an unfamiliar landscape full of dangers.

Crisis, climate, challenges, sustainability, circularity, diversity, inclusion, acceptance, activism, time, and value are words so often repeated in 2020 in the fashion industry. One can no longer discern their precise meaning if many of these words even have any meaning at all now. Each of these words collectively defined a year in fashion in which everything is turned upside down repeatedly; one crisis succeeds another without end.

The period of the belle époque in the early twenty-first-century fashion ended on March 3, 2020, at around 7 PM as guests strolled out into the empty courtyard of the Louvre, following the Louis Vuitton women’s collection show with ironically a theme around the meaning of time and duration in fashion. The show’s spectacular backdrop was a wall high human tableau consisting of over 200 choral singers dressed in historical costumes from the fifteenth century to about 1950. The details of the clothes so vivid that fashion history for a moment came alive where past and presented all share the same temporal space, albeit however brief.

A few weeks later, the annual super Met gala was to be postponed as Europe. The U.S. and much of the world was under shelter in place order and, then a few months later, to be eventually outright canceled – foreboding a succession of events that summarized the rest of the calamitous year following the end of the Paris Fall show season.

The unexpected pandemic shattered the fashion world’s fragile image with global lockdowns and a complete cessation of production activities that jeopardized an industry’s careful rhythm that depended on many external factors not always within its control.

The production and delivery of the spring 2020 orders destined for stores were suspended as all retail establishments were shut down while e-commerce continued to hum the extra potential revenue for brands under duress. The fashion show calendar system came under attack with groups forming factions about how and when to show as the upcoming resort seasons with several mega destination shows like Chanel, Dior, and Gucci all canceled.

At the same time, designers like Dries Van Noten questioned the effectiveness of this entire show system. Meanwhile, mega brands Gucci and Saint Laurent withdrew from the Milano and Paris fashion weeks’ formalities to launch new collections when, where, and how to be determined by the respective brands. The show weeks had been moved to digital formats for men’s spring 2021 and Paris fall 2020 haute couture in the immediate horizons.

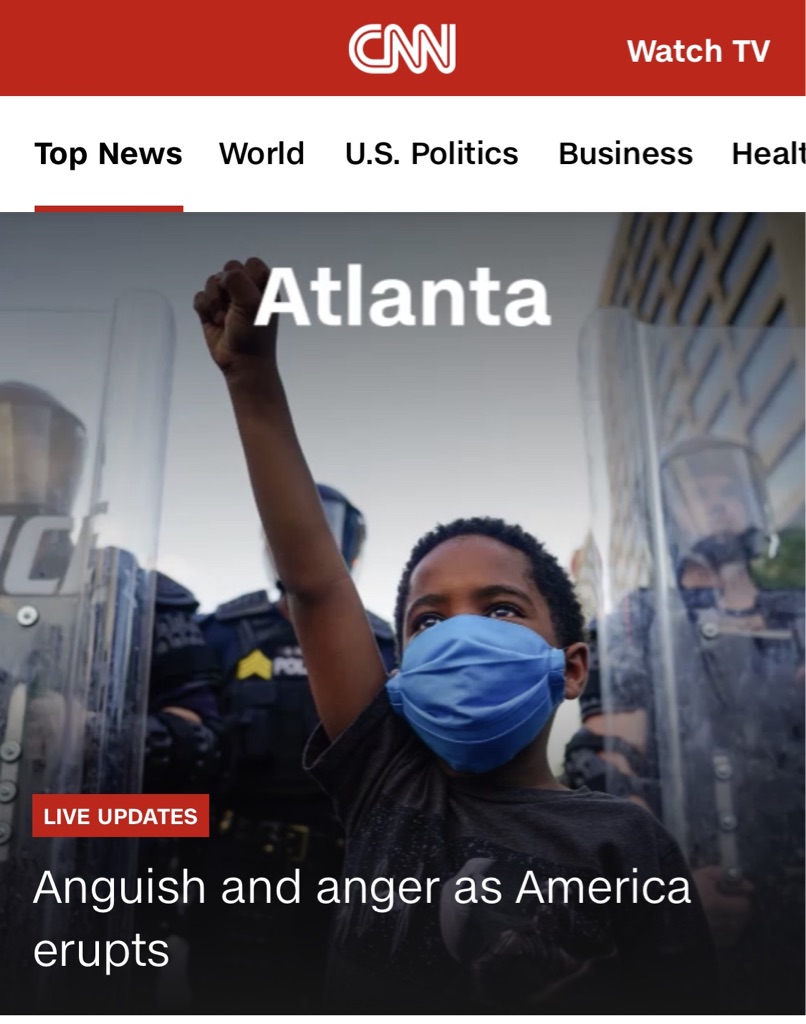

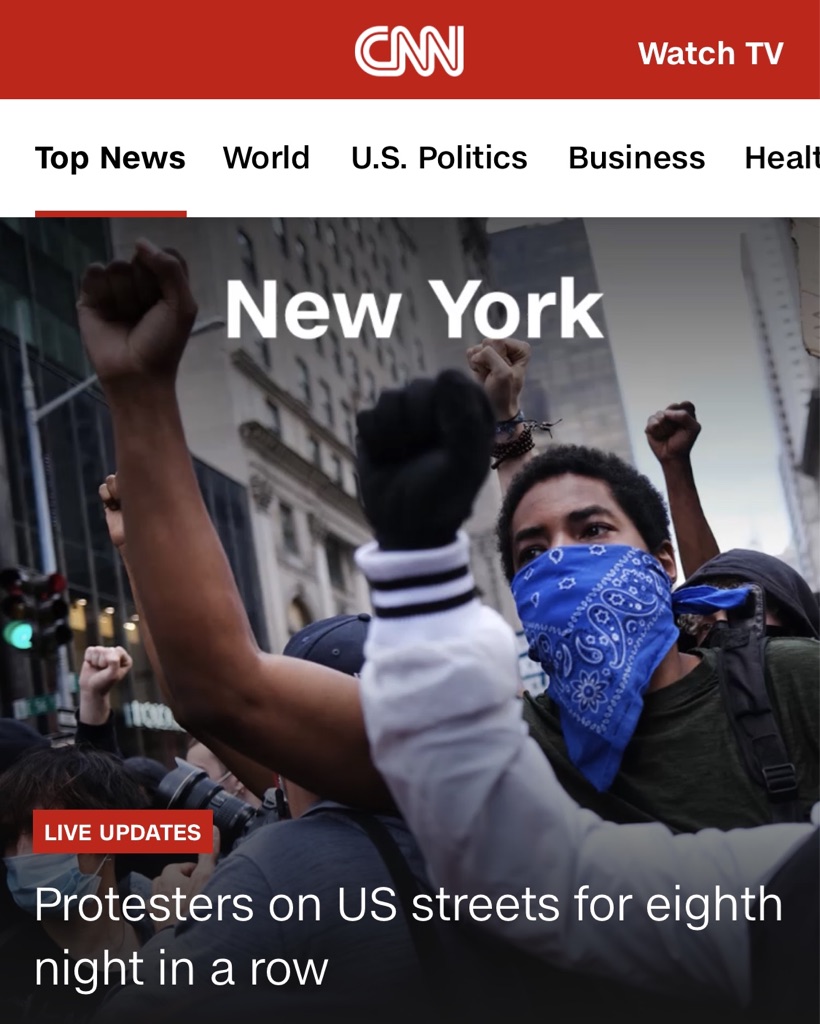

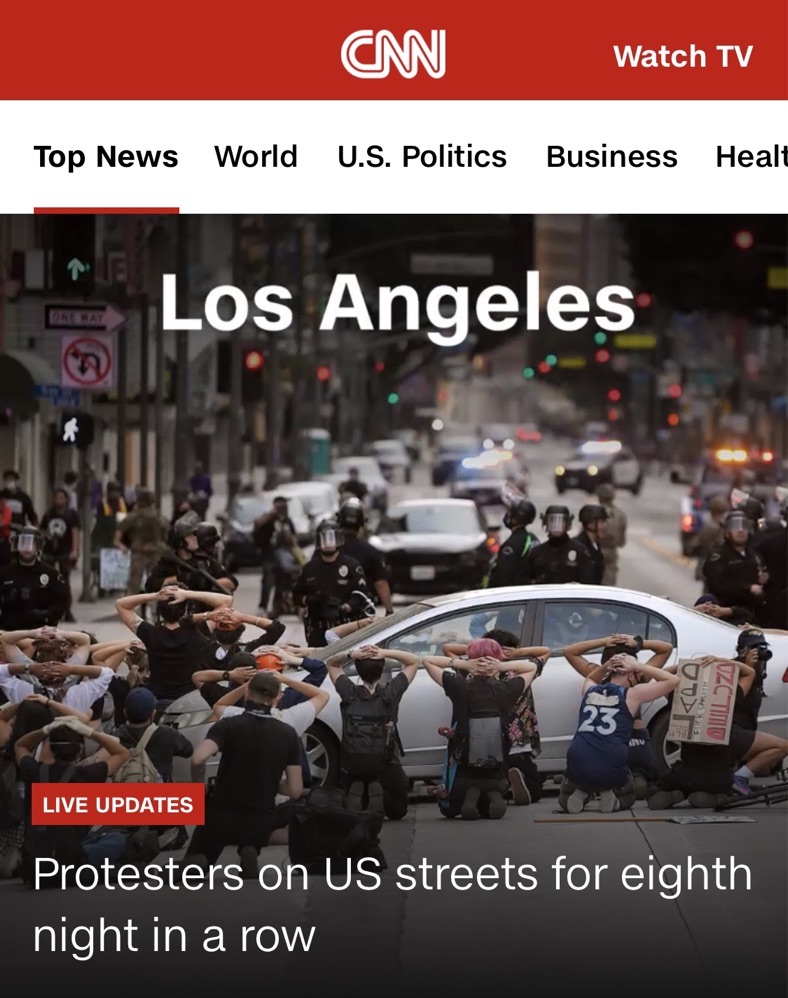

Just as the retail stores began very limited reopening at the start of summer came another crisis, social-political this time that again galvanized the already fragile fashion industry under the severe strain of a full stoppage from production to distribution to sales. In the U.S., the Black Lives Matter movement originated in July 2013 with the acquittal in the Trayvon Martin killing began its protest in the early days of June against the police brutality and the inherent racism prevalent in twenty-first-century America after the killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis.

The summer of racial reckoning first across the U.S. then spread to London and Paris, as the young generation stood up and said no more to discrimination and to being second-class citizens. As these young kids take to the street, their actions exposed a long time dormant racial inequality at all fashion industry levels now under assault for rapid response.

The Black Lives Matter or simply BLM became the symbols of a new era of civil rights experienced by youths across the country, real experiences rather than those from the history books’ accounts.

Suddenly, fashion got really involved in social and political matters with every brand, even though most have never uttered a word against racial inequality even in their businesses and were so fast in posting black squares on all their social media networks for the unique Blackout Tuesday on June 2, 2020.

The BLM movement presented a moment of reckoning within the fashion industry ranks, long too comfortable with brands’ status quo to media. The backlash to these years of structured racism seemed to begin to shatter as employees and ex-employees came forward to testify their treatments on the ubiquitous social media.

Examples of the controversies at Bon Appétit and other media strongholds demonstrated the urgent need for quick remedies.

Major brands like Prada, Gucci, and Chanel have rushed to appoint ‘Chief Diversity Officer’ within the corporate structure to alleviate concerns about racial disparity at large in practice.

Here, the irony at the center of all political, cultural, and social correctness seems much more of a momentary solution to quiet the storm than a long-term solution.

Even media organizations like WWD and Condé Nast have hired a CDO, chief diversity officer. Yet the central question no one bothered to ask then and now is why are all these ‘diversity’ officers all black people instead of people from across the POC fields. Is it really about diversity and inclusion, or is it solely about black diversity and inclusion?

The immediate response to help black designers and black-owned businesses – all worthwhile enterprises – also used diversity and inclusion as buzzwords for funding. Words do matter, and so do actions undertaken for these words.

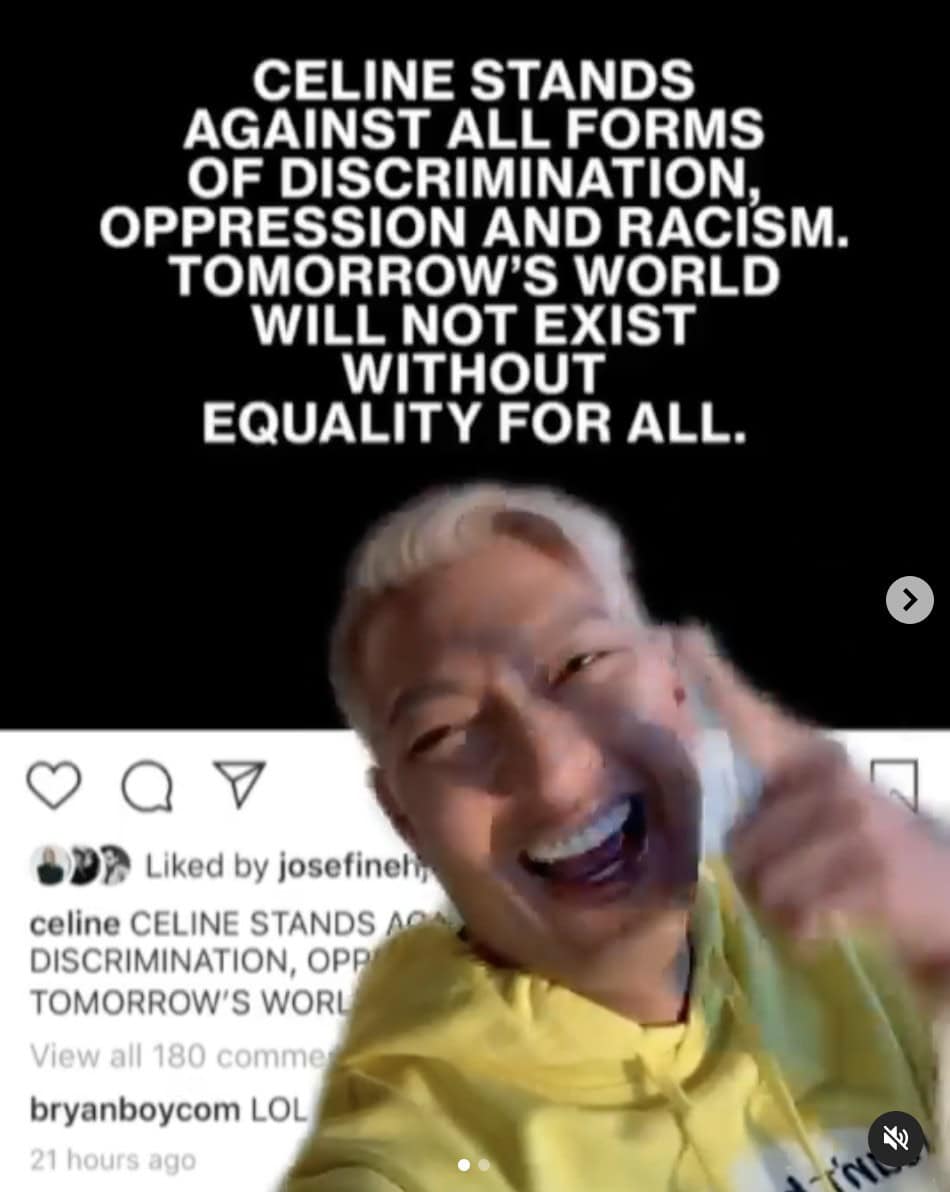

The influencer and newly minted TikTok superstar Bryanboy called out Celine for embracing diversity with Instagram posts when the images from the brand’s advertising showed mainly all-white models since Hedi Slimane took over as creative director. While Bryanboy brought up as valid business points as brands today, have to sell to many different customers in the global market, so it’s not abnormal to expect the seasonal visual representations to reflect or, at the very least, celebrate the diversity of the clientele.

The essential question is this – is an affinity for a specific aesthetic to be called racist? The fashion industry is great at these kinds of performances; these kinds of dressing to look the part. This time as political activists.

Isn’t it mere hypocrisy to call out those influencers who posted black squares for the day and even those who pretend they were actually at real protests instead of standing on the sideline holding cardboard while using the real protesters who marched behind them as mere selfies props?

It is now safe to have discourse on social and political issues in fashion, the kinds of conversations that designers outside the primary fashion system like Telfar, Rio Uribe at Gypsy Sport, and the recently resurrected Hood by Air by Shayne Oliver. They live and breathe true diversity and inclusion without ever having to mention those unnecessary words, or worse, have someone within their organization call out if they don’t represent the ‘people.’

Telfar

Hood by Air

Gypsy Sport

These designers are authentic, they act authentic, and they don’t need words to prove their actions.

The disruptions of manufacturing and production brought attention to fashion’s favorite theme of the year – sustainability.

Sustainability has become the ultimate Holy Grail for fashion brands hooked on the idea of wooing the young generation by doing whatever is possible to espouse an environmentally conscious platform vertically to transform how luxury goods are produced, then marketed. Young people don’t just buy the products; they purchase the products from companies they see share their values.

There are reasons to re-examine the methodology of production and assess whatever necessary alterations and substitution of materials to reduce waste at all levels.

Yet, there is something false in how luxury brands embrace sustainability as a word and do minor projects for marketing and communication purposes than for climate change contributions. No fashion brands, luxury or not, have ever embraced the notion of less production and less consumption as a way actually to reduce waste and pollution.

At the end of the day or, more precisely, the quarter, sustainability is just mere background noises quickly drowned out by the need for higher and higher revenues to enhance the brand’s values measure in nominal growth in revenues and profits.

Real sustainability in fashion lies in reducing the global production of clothes, handbags, shoes, and sneakers on the one hand. On the other, the reduction in consumer demand for new products each season.

Think of it this way – suppose that all the governments in the world impose a strict regulation forcing all cars and trucks in existence to increase each vehicle by only one mile per gallon. This two-mile per gallon extra globally would yield more significant pollution and carbon reductions than the contributions of all the hybrids and electric cars that have ever existed. Yes, it’s nice to have a shopping bag made from recycled paper waste; yes, it’s nice to know a few garments are manufactured from recycling and upcycle materials; yes, it’s nice to align brand values with consumer’s values. But these feel-good measures do little to hinder real waste and do little to reign in pollution.

The fashion industry is so good at doing just the very least and yet markets the smallest impact projects as mega reforms!

The pandemic interrupts fashion’s relentless march forward, brushing aside criticism of the potential waste and the pollution crisis of developing countries producing cheap goods on cheap labor for rich countries.

Newcomers like Bianca Saunders, Emily Bode, Bethany Williams, and the crops of young designers who have just entered the fashion system imprint their values onto their clothes. However, the luxury brands responded to the youth’s demands who espoused sustainability as a core value in the usual manner by orchestrating marketing campaigns rather than real reforms. A few items made from recycled parts serve as a portal to these youths’ souls, rather than confronting the momentous waste and pollution from the production of goods. At least the young designers are operating at a scale that is feasible for them to match their products’ values.

Until the large luxury brands decide between shareholders and the earth, sustainability in luxury is a moot point.

And in 2020, creating a local community is prime in fashion. Look at the way Francesco Risso at Marni, Telfar, and Pyer Moss has cultivated a closely-knit community around their fashion brands. Kerby Jean-Raymond organized his office to raise funds for black businesses in trouble with a ‘Your Friends in New York’ initiative with the Kering Group. Samuel Ross of A-Cold-Wall* is doing the same for small black businesses in London.

2020 is the year the culture and the fashion culture begin to merge at different junctures but significantly more so with the young designers emerging into the fashion scene.

Power is the authority of authenticity, measured in community initiatives, not in the reach metrics. How to cultivate a core global community of devoted fans sharing the same ideals and the same aspiration and hopefully the same kind of clothes, sneakers, and handbags is now the key to fashion success.

Young designers today are stepping forward as cultural influencers themselves, displacing the perennial Instagram stars and TikTok celebs. They create authentic narratives to anchor brand values and participate in the broader pop culture to shape conversations around specific topics. In fathoming innovative ways to create fashion at a time, it seemed unnecessary.

Sure the pandemic shook up the way fashion elite thinkers thought of the endemic system; whether any temporary measures taken to stem further losses will result in permanent changes remains unknown. But knowing how conservative the industry is not in the image would not be abnormal to say how fast brands want to return to normal, aka to what was and not what has shifted drastically.

Murky nighttime darkness fell across the fashion terrain but unlike a total solar eclipse projected to last into 2023, upending the precious equilibrium so desired and optimized by industry experts. Thinking anew should be natural in an industry populated by a vast array of creative experts as well as corporate business acumens.

2020 is the year that luxury fashion, while still very much within its tall ivory towers, seemed to have begun cracking here and there that perhaps will eventually lead to the scaffolding coming off soon. Despite all its powers and the will to readily deploy assets and resources to shore up its interests, a small gulf emerges today – say a little fissure – as the price of admissions for these major brands’ products is becoming prohibitively expensive. Perhaps, also because the products offer little in terms of community associations.

Are the old formalities of fashion coming right back as soon as the pandemic is under control? It’s possible, but not likely. For once, there are now the possibilities of another roadmap, one taken under duress and one that can change how fashion can operate soon.

Is the fashion industry so entrenched in its ways that real innovative changes remain more elusive than otherwise thought?

Is there a Petrarch, the fourteenth-century Italian poet, or a modern Cicero performing the tasks now as these Italian thinkers did in ushering the Renaissance?

The problems exposed by the pandemic in 2020 are still the same problems facing fashion in 2021, issues that require foresight and leadership. “What’s needed is imagination,” as the fictive character Jean Tarrou said in La Peste. Tarrou is right in his assessment of the ways to solve the crisis during the plague year. We’ll stay tuned for these developments as they surface over the coming months.

What about physical fashion shows?