New Clothes and New Words Defining Today’s American Fashion

By Long Nguyen

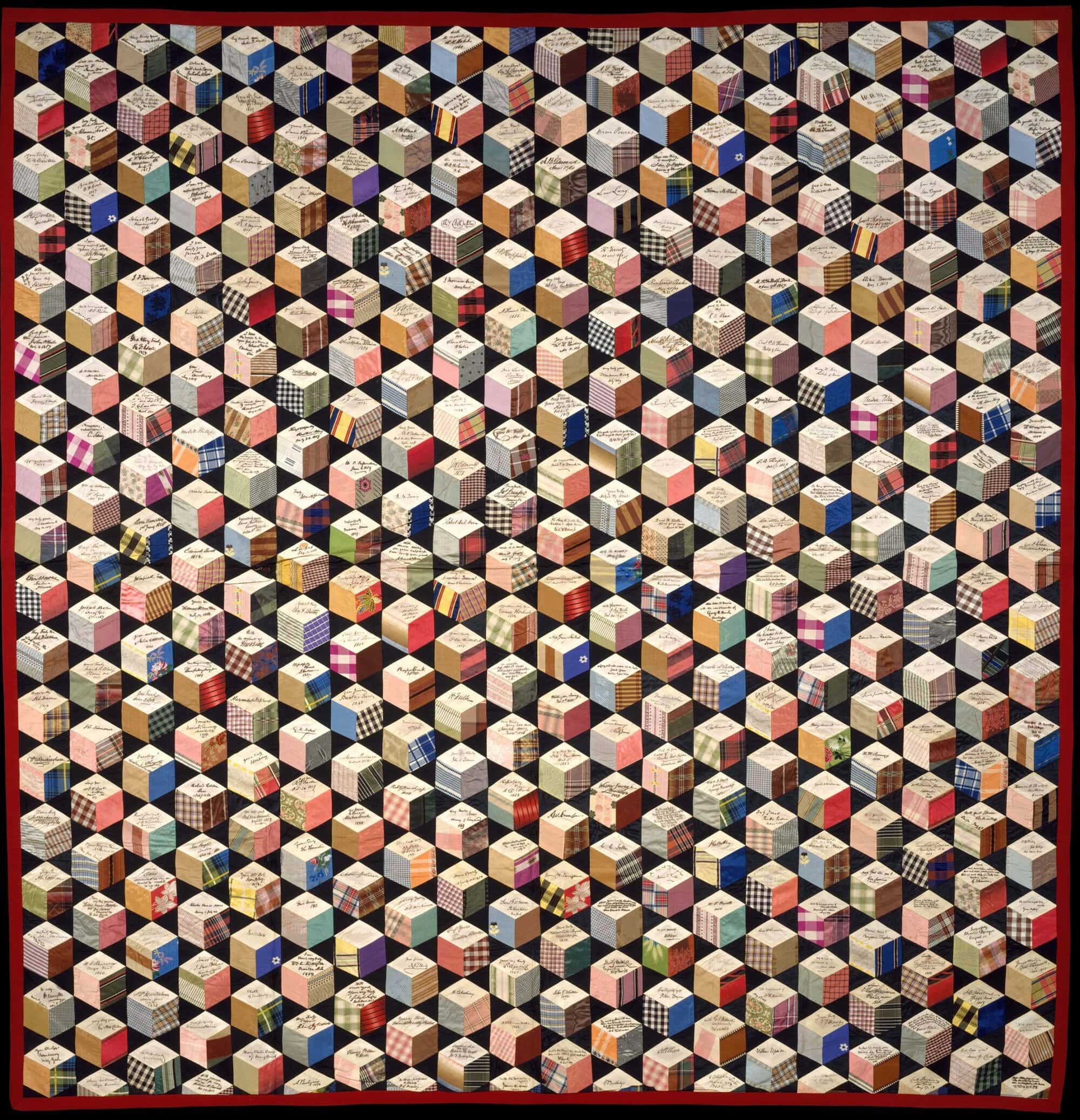

Common ground. America is not a blanket woven from one thread, one color, and one cloth. When I was a child growing up in Greenville, South Carolina, my grandmama could not afford a blanket, she didn’t complain, and we did not freeze. Instead, she took pieces of old cloth – patches, wool, silk, gabardine, crocker sack – only patches, barely good enough to wipe off your shoes. But they didn’t stay that way very long. She sewed them together with sturdy hands and a strong cord into a quilt, a thing of beauty and power and culture. Now, Democrats, we must build such a quilt,” said the Reverend Jesse Jackson at the Democratic National Convention in Atlanta in 1988.

In introducing part one of In American: A Lexicon of Fashion/An Anthology of Fashion exhibition at the Anna Wintour Costume Center Gallery at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the seventy-fifth years of the Institute, Max Hollein, the Marina Kellen French Director of The Met, said that “the organizing principle of this show is a patchwork quilt, in itself is an American cultural item.” Hollein emphasized the scope of the show to include “objects by established designers are set alongside emerging talents whose design comprise more than seventy percent of the works in the exhibition, most appearing in our galleries for the very first time.”

The exhibition brings to light how designers in the United States today focus more on emotion than on practicality that define the work of designers from the previous generation,” Hollein said. “The renaissance of American fashion taking on social, political and philosophical issues to move fashion culture towards a greater plurality and diversity.”

“An emerging generation of designers are bringing a new voice to American fashion and one that prioritizes diversity, inclusivity, and sustainability. ‘Lexicon’ presents a revised vocabulary of fashion based on its expressive qualities and the emphasis on fashion’s emotional resonances inspired by the work of a new generation of designers who prioritize sentiments. This new lexicon intended to articulate the heterogeneity of American fashion that can’t adequately describe through a narrowly and universalizing definition,” Andrew Bolton, the Wendy Yu Curator in Charge of the Costume Institute, said of the need for new words for a new fashion era.

The patchwork quilt is a fitting metaphor for American fashion in its diverse aesthetics,” Bolton remarked.

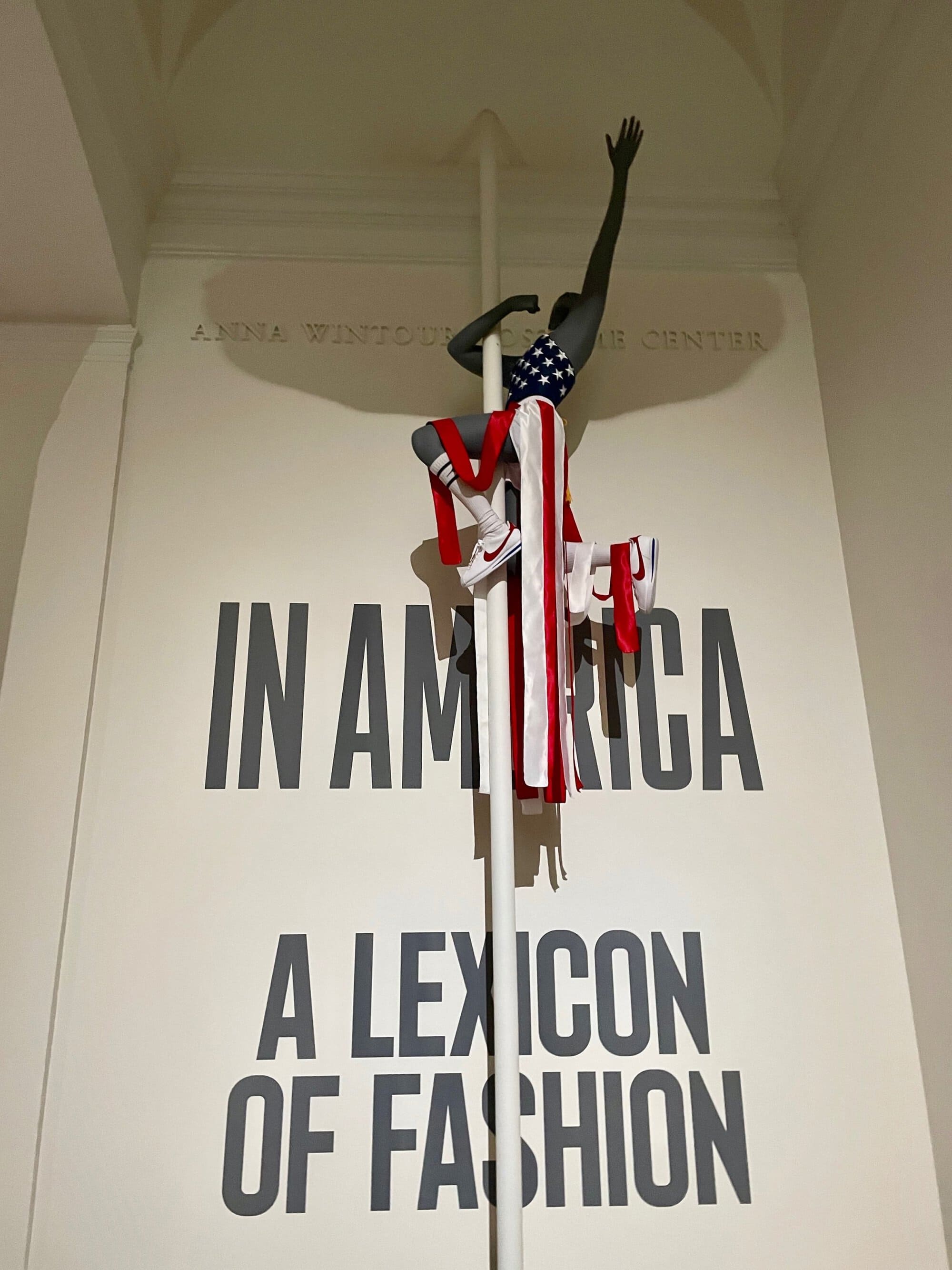

At the entrance to The Costume Institute’s Anna Wintour Costume Center main section of this Met exhibition, a mannequin mounted on a steel pole dressed in an American flag tank top with long fringes, white-hot pants, and white Nike Cortez leather sneaker, an outfit created by Rio Uribe founder of Gypsy Sport. Uribe made the look for a dance performance by the LA-based artists Gerard & Kelly titled State of in Paris for the FIAC Festival d’Automne à Paris in October 2017 at the Palais de la découverte. “I was inspired by the United States’ perpetual state of unraveling,” Uribe told me via Whatsapp from Los Angeles.

On the left side is Prabal Gurung’s white lean dress with a one-sided ruffle sleeve and a sash with the words in capital letters – WHO GETS TO BE AMERICAN? – from the finale of his Spring 2020 show.

Long Nguyen Archives

Gurung’s social-political activism responded to the changing circumstances and the rise of a broader recognition of the struggle of minority representation across society that has been suppressed. Gurung launched in February 2009 at the Flag Art Foundation in West Chelsea, at the height of the Great Recession. I remembered the clothes were updated luxury, sporty and sexy without going overboard, but nothing that would indicate an eventual turn towards personal and brand activism.

It wasn’t until his Fall 2017 show that Gurung sent out the finale models in white t-shirts with printed slogans – ‘I am an immigrant, ‘Revolution has no border,’ ‘Nevertheless She Persisted,’ or ‘The Future is Female.’ From that moment on, Gurung has been on a path to elevate social consciousness whenever the occasion called for his activism, like in the recent anti-Asian hates campaign early this spring.

I clearly remember when young kids like Alexander Wang, Jason Wu, Derek Lam, and Philip Lim came onto the New York fashion scene over a decade ago. They are known as Asian-American designers instead of just designers. The same was of all the Black designers ever emerging onto the fashion terrain – Black American designers. The central question remains whether the defining mark is still on race, and that may not exactly be a bad thing. But now, the mood is changing and affirming their Asian roots.

As Bolton said in his introductory remarks, new language and words are crucial to today’s American fashion as they form an identity, primarily ethnic and non-mainstream identities. Growing up, the idea of Americana was certainly about not recalling the different roots that brought many immigrants to the U.S. My journey here in American is not as self-revealing as the stories in ‘Journey to the West’- a Chinese novel from the 16th century Ming Dynasty-era narrating the pilgrimage of a Buddhist monk to fetch in the process of self-discovery.

New words to make the clothes less ephemeral, inscribing and evolving them within a permanent stature.

In my own experiences, the demands for assimilations came in several forms. First is the question of language. Bizarrely I never could adopt a proper way of speaking English or American English and talk about the language with a heavy accent. Upon opening my mouth and utter any words, it was and still is like giving away the big secret – ‘he is a foreigner’ is what came to people’s minds without saying it aloud. But preserving the ability to speak my native language has been crucial in retaining a different identity.

It was somehow inappropriate to speak other languages besides English that, to this day, I still talk with a heavy accent. And perhaps because of my heavy accent, I was never considered by others and myself to be American in any way but more as a foreigner living here. And, my accent instigated many racial slurs over the years. But strangely, I thought the insults were empowering and an affirmation rather than a put-down.

I experienced a great deal of racism but little in terms of any catharsis worth mentioning. More often than not, ranges of people screamed ‘ni hao’ at me, not knowing that I was not Chinese. You can’t insult someone incorrectly. The racial slurs tell the fact of difference and not assimilation. One thing for sure, though, is that I never have that sense of diminished identity either way. And now it is the voices from these different identities and points of view that are coming strongly onto the surfaces of fashion and the culture/society here at large.

Image | © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Fortunately, I retained the ability to speak Vietnamese over these years, using the language in whatever ways possible, even in minor things like counting how many laps I have run around the track. I had refused to pay this tremendously high cost of assimilation, losing one’s roots as it is not worth it. Now authentic identity is cherished again at last.

Fashion today, especially American fashion, can no longer be divorced from identity politics and multiculturalism at all levels. It sure is a demonstration of a changing of the guards for fashion in America.

Fashion is both a harbinger of cultural shifts and a record of the forces, beliefs, and events that shape our lives. This two-part exhibition considers how fashion reflects evolving notions of identity in America and explores a multitude of perspectives through presentations that speak with powerful immediacy to some of the complexities of history. In looking at the past through this lens, we can consider the aesthetic and cultural impact of fashion on historical aspects of American life,” Mac Hollein, the Marina Kellen French Director of The Met, said in introducing the exhibition preview.

Image | © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

In this part one of this yearlong exhibition in celebration of the museum’s Costume Institute 75th anniversary – In America: A Lexicon of Fashion/An Anthology of Fashion, the show’s primary focus is on establishing a novel outline of modern American fashion in terms of defining the clothes through a new vernacular.

A vocabulary expresses the mood of the garments, thereby offering insights into the mindset of the designers making these unique clothes. By ‘complexities of history,’ Hollein means to say The Met as an institution will now collect and showcase the range of designers currently working from all different backgrounds who have contributed to this massive quilt of American fashion.

American fashion has traditionally been described through the language of sportswear and ready-to-wear, emphasizing principles of simplicity, functionality, and egalitarianism. Generally denied the emotional rhetoric applied to European fashion, American fashion has evolved a vernacular that tends to sit in direct opposition to that of the haute couture,” Bolton emphasized.

Part One of In America: A Lexicon of Fashion is about reframing the description of American fashion away from the functional and the practical valuation often ascribed to designers creating clothes here. This Met show also expands on recognizing the work of BIPOC designers, and they are associated narrative central to a new vision of culture and fashion.

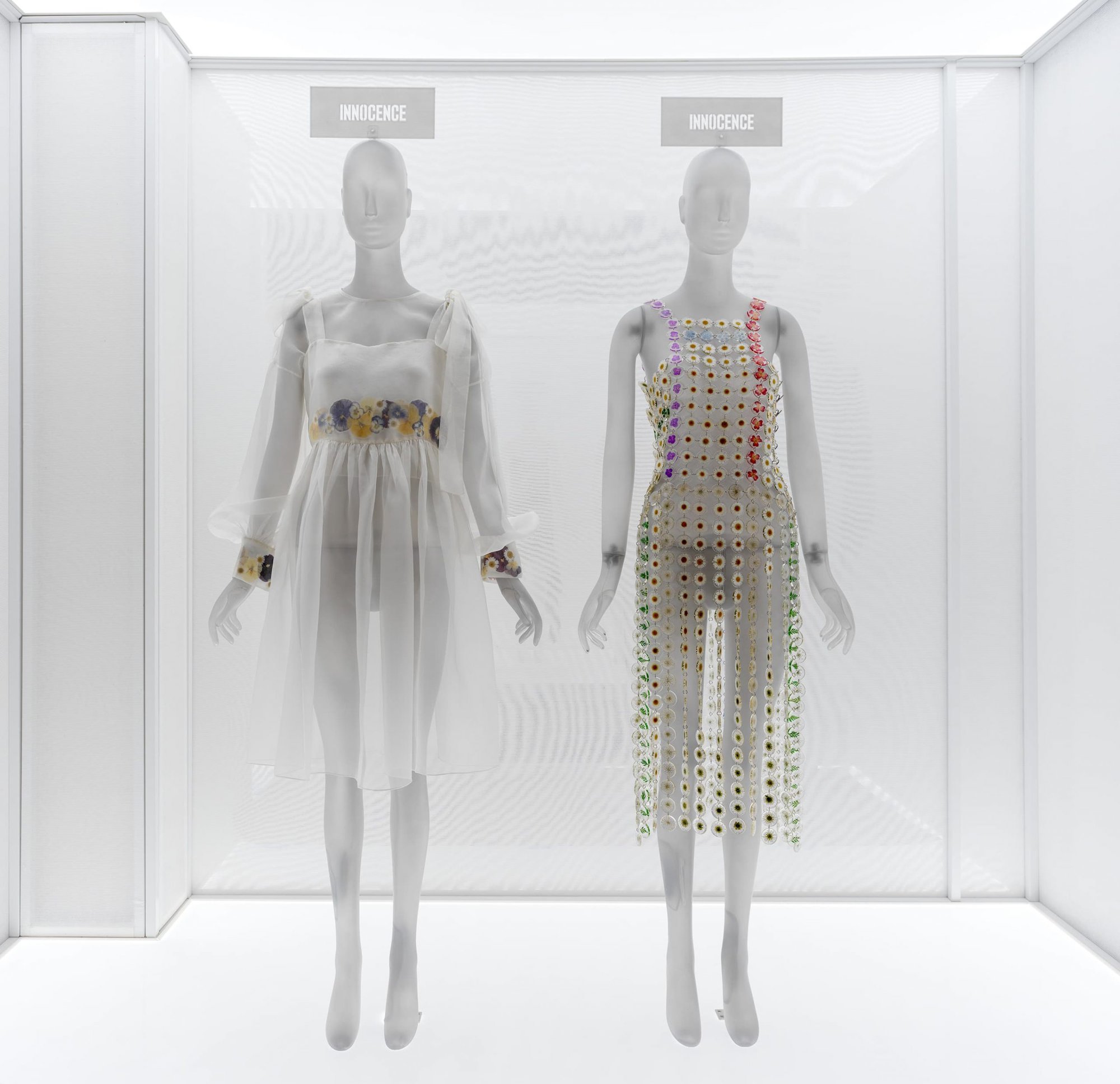

Inside the frame of these see-through rectangular boxes are the new canvases in the forms of cotton, wool, linen, and recycled fabrics. The Met curators give these complete looks new adjectives/nouns, and each of the twelve sections has multiple garments with headline expressions furthering refining the section’s theme.

In the section ‘Consciousness,’ salvation is for an up-cycled 1920s vintage dress by Tara Subkoff for spring-summer 2001 Imitation of Christ and gratitude for a deadstock dress from Hillary Taymour’s fall-winter 2021-2011 Collina Strada. ‘Joy’ is a black wool short dress with a button heart shape embroidery from Patrick Kelly’s fall-winter 1986-1987 collection. Camaraderie describes a fall-winter 2021-2022 grey jersey cotton twill, white cotton shirt, and grey cotton knit pants from ERL by Eli Russell Linnetz. Mindfulness is the suggested word for fall 2021; partially shred cotton denim with lace and chiffon intertwines by Everard Best from his label Who Decide War.

Image | © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

‘Exuberance’ is the description the Met curating team gave to the supersize red plaid silk taffeta dress with giant nine-foot wide 19th-century crinoline ball gown that Christopher John Rogers created for his fall-winter 2020-2021 show. Emotional and transformational buzzwords added in the accolades, but perhaps the anger and an explosion of the self is a great way to be noticed can also be words attached to this expansive garment posited at the main exhibition entrance.

Is it wrong to also read anger as another powerful emotion into the beauty of that Rogers’ red crinoline gown?

Image | © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

This first part of the exhibition put a particular focus on the young designers. In the last five years, their creative fashion has altered the aesthetic dynamics but not yet the commercial power of clothes, especially those made by American designer brands.

Enclosed in transparent rectangular boxes designed by LAMB Design Studio, the one hundred men’s and women’s outfits gathered from designers from the 1940s to the present eschew any chronological order. Each of the outfits is under one of twelve selections of words defining the emotional qualities of these chosen clothes. This Met exhibitions hope that these new words – nostalgia, belonging, delight, joy, wonder, confidence, strength, assurance, desire, comfort, affinity, and consciousness – will express a renewed sensibility to look at modern American fashion.

Image | © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Image | © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

‘Belonging’ is the white dress belonging to Prabal Gurung Spring 2020 collection with the ‘beauty pageant’ sash WHO GET TO BE AMERICANS, and unity is for the red and white silk flag dress by LRS by the Mexican-American Raul Solis. “Assertion’ is the black wool cape/jacket with white shirt insert and shorts by Shayne Oliver for spring-summer 2017 for Hood by Air. Multilayers of words for the new network represent the breadth of diversity of American fashion today.

This new repertory comprises a young generation of designers who bring their life experiences and values enmesh in the clothes and the community they have been able to fabricate single-handedly. In what they experience in their community, the epic moments in their lives become their epic collections, at times outrageous in daring and in beauty.

Gallery View, Assurance

Gallery View, Comfort

The fashions these young kids resonate so profoundly with their peers and fans simply because there is that abundant and pervasive identification from these fashion visions as resembling circumscribed lives, particularly so in the past year and a half. The pervading undercurrent of social/economic anxiety ingrains with the deep strain of societal structures that prevent the advancement of non-whites in so many businesses, including fashion and media.

Image | © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Today fashion creative and business relationships align with values and advocacy efforts, and the physical clothes are like protest signs now wearable instead of solely on cardboards or posters. But these new value consciousness aren’t new as such, and they are intrinsic parts of companies like Patagonia and Ben & Jerry’s Ice Cream.

A question remains if these museum-level art exhibitions pose a potential for anchoring brands with plumbing the nostalgia vaults for practically never-ending re-tooling instead of creative innovation.

Steven Sprouse

Rick Owens

Vaquera

Bstroy

Who Decide War

Hood By Air

Great fashion is about the right time to capture the right moment, with the veracious tempo portraying the changing mood of the current instance.

Against all these background noises and uproars about the rebirth of New York City and its anchoring homegrown fashion, what exactly is the picture of American fashion emerging from the actual Spring 2022 New York shows right after Labor Day weekend?

At the recent Spring 2022 shows in New York, the young designers took command with their storytelling rather than the bigger brands continued borrowing from other histories and other narratives. It isn’t just about their personal accounts, but they are so passionate about the clothes they make and sell.

Collina Strada

LRS

Eckhaus Latta

NIHL

Tom Ford indeed did own the social media Olympic Gold with his carefully calibrated array of sports separates to be worn in the timeless (no day or night) Internet age and rage. Meanwhile, Thom Browne secured American fashion’s rightful place in design and craft, rivaling European heritage brands. The Rodarte sisters continued to send out pretty hand-made dresses. At the same time, Joseph Altuzarra and Proenza Schouler returned to New York with a soft blend of knits and separate sets perfect for any summer outing – backyard or far away islands and Gabriela Hearst and Collina Strada both fortified her ‘value’ brand of fashion. Michael Kors lured guests to Tavern on the Green for a lesson in chic sensuality while LaQuan Smith had his outing of signature cut-out slim dresses on top of the Empire State Building. Elsewhere during the short week, commerce rather than design dominated the discourse. That is less interesting to see.

Something else is also telling at these New York shows. The new audience consists of a community of ‘ultras’ – the word for super hardcore fans at European football matches – from outside of the big fashion industry and old media types that typically populate these shows.

At the Who Decide War show on top of the former Intrepid battleship, now a museum on the Hudson River piers, the spectators consist primarily of fans of the brand which came to support Everard Best inventive reworking of dead stock types of denim into sumptuous unique garments. I sat a few seats from the Pyer Moss designer and Reebok creative director Kerby Jean-Raymond and, among others, close friends of the brands. The night before in Bushwick at Raul Lopez’s Luar show, it was the exact caliber of an audience who came to cheer on a communal friend. Everyone partakes in more than watching a fashion show, rather a communion of a sort.

“My inner pearl was released from its hard, tough, rigid shell,” the Brooklyn-based Dominican Raul Lopez said of his beautiful mixtures of fluid, soft and sexy suiting combined with his love of deconstruction on pants, turning a t-shirt into a cut out the cape. Lopez made a light violet dress shirt tucked into soft mauve sweat pants look enticing, especially to the packed crowded in Bushwick late on a Saturday night.

Newcomers like Houston-born menswear designer Kenneth Nicholson shared a collection that reminisced his late teen years. These clothes are expressed in black and white polka dots around slouchy shape jackets with matching shorts or as long blue cotton or floral flare shirt dresses. It isn’t about that easy commercial sell piece. It’s about the hard road to get more of his young peers to feel these kinds of garments. The same can be said of Connor McKnight’s readjustments to more classic garments like a plaid long sleeve polo and matching shorts as summer’s new suit as an alternative to a black cropped jacket loose fit pantsuit. Launched in the pandemic year, McKnight hand-made these imaginative staple clothes from home in Brooklyn. Unable to show in the pandemic year, LA-based Sergio Hudson finally had his chance to reveal his base’s sculpted tailoring and sparkling dresses.

Collina Strada at Brooklyn Grange, Brooklyn

Peter Do at Skyline Drive-In, Brooklyn

Sergio Hudon at Spring Studios, Tribeca

Oh, and talk about Brooklyn; it’s the new big hub for creative fashion. Vietnamese-American Peter Do did his first show for his seventh collection with fluid control tailoring. Mike Eckhaus and Zoe Latta did their twentieth collection on a street block, touting their fantastic and uncompromising approach to fashion design. Their clothes are a bit ‘undone’ and create that crucial connection to youth – something Eckhaus Latta fully mastered in their authentic way in the pair’s decade journey. While talking about authenticity, Stuart Vevers’ streetwear Coach collection made desperate attempts to get to the youth with little of the requisite feeling.

Pivoting to youth isn’t about making a few outfits that ‘look young’ and street.

Big brands like Coach should take heed to designers like Patric DiCaprio and Bryn Taubensee at Vaquera. In a small alleyway – Cortlandt Alley – not far from Chinatown, the Vaquera pair sent their ‘models’ practically running down the tiny alley. Each grasped the garments floating over their bodies like a giant ball gown made from black plastics resembling trash bags and among the more wearable clothes including a flare sleeve white cut out t-shirt/long dress over a black and white stripe underdress. The mood resembled some of the fashion shows in the late 1990s, where the kids then touted their utter creativity in a faraway locale in the most low-tech production possible.

Tom Ford at David H Koch Theater, Lincoln Center

Vaquera at Cortlandt Alley at Walker Street, Chinatown

The Vaquera show was just before the high gloss Tom Ford extravaganza at Lincoln Center, where waiters offered drinks and TF facemasks to the all dressed up guests, but it seemed several universes apart. What a study in contrast!

Nicholson, Best, McKnight, Hudson, or Raul Lopez at Luar (a new collection of camp basics after a three-season hiatus) do not base their fashion on borrowed heritages or inspirations. They don’t need to look at arts or books or movies. They look at themselves and those around them. More important is that their audience begins to see themselves as mirrors of the runway they are witnessing. That’s how these young kids are building their independent fashion enterprises.

While the American social and economic fabric may be unraveling with the unprecedented rise in income inequality across the country and subscriptions to hardened partisan’s beliefs even at actual economic costs, the fabric of American fashion is more vital now than ever. They are coalescing around the network of young designers across the country. Each of these designers contributes to a shared conversation on creating their communities apart from pushing products.

That’s what the designer Telfar did, launching a Telfar TV with no content yet save for the promise of a new round weekend bag and not a sign nor a mention of clothes.

Looking at this first part of The Met’s American fashion exhibition, I wonder how it is possible that perhaps the most premier of all global cultural institutions is so late to recognize a new reality in fashion. Fashion has been quaking for more than five years before these seismic tremors reach inside these walls.

Hopefully, though, the Met will collect these new clothes as part of the permanent residents at the Costume Institute. Furthermore, now that this giant institution has backed the work of these young designers, it is a convenient time for the structural support needed to maintain and expand these diverse expressions and writing through clothes.

As Hollein, the Met Director, affirmed in his introduction, about 70% of the fashion shown is brand new to the museum and on display for the first time in this part one.

That’s progress.