Remembering the legacy of seminal creatives across fashion and design.

By Angela Baidoo

While many were blindsided by the sudden passing of the creative powerhouse that was Virgil Abloh, and one of the industry’s most beloved master craftsmen Alber Elbaz in 2021. This year has been no less poignant in the names, many who were front-row fixtures, cultural trailblazers, and multi-hyphenate storytellers who took their final bow in 2022.

Here, at The Impression, we pay tribute to the names across fashion, photography, editorial, and entrepreneurship whose impact will continue to be felt in seasons to come.

André Leon Talley

Vogue Editor, 73

The loss of a formidable force within the fashion universe (to say industry, somehow seems to diminish his influence), André Leon Talley’s passing marked the loss of not just an icon, but a fountain of knowledge, and a beacon of hope for a generation of black and brown creatives. Born in 1948 and raised in North Carolina. He majored in French Studies, which he later abandoned for his true calling in New York. Securing an internship with former Vogue Editor Diana Vreeland, his career with the magazine spanned four decades, from 1983 to 2013.

To quantify, his impact has been more than influential for those who knew and worked with him. His lifetime of achievements included his most notable role as Editor-at-large at Vogue, working alongside Andy Warhol at Interview magazine, WWD’s Paris Bureau Chief, and resident interviewer-in-chief at the Met Gala. Behind-the-scenes Talley was a staunch advocate of diversity, mentoring model Naomi Campbell and more recently New York-based designer Laquan Smith, playing an instrumental part in reviving the career of John Galliano in the 1990s, and ensuring the burgeoning wave of designers from Japan were featured among the pages of Vogue. As well as scoring the coup of styling former First Lady Michelle Obama for her first Vogue cover.

He developed a strong sense of personal style which complimented his 6-foot frame, and in later life could be found draped in statement kaftans or robes in bold colours or rich brocades, many of which were custom-made by his fashion friends Tom Ford, Valentino, and Karl Lagerfeld.

Ascending to fashions upper echelons, Talley was a key figure on the front rows at Paris Fashion Week, yet despite his status he made no bones about experiencing many of the issues which were exposed of the industry in 2020 – namely racism, sexism, and ageism – through his second book ‘The Chiffon Trenches’, his first memoir A.L.T. was released in 2003.

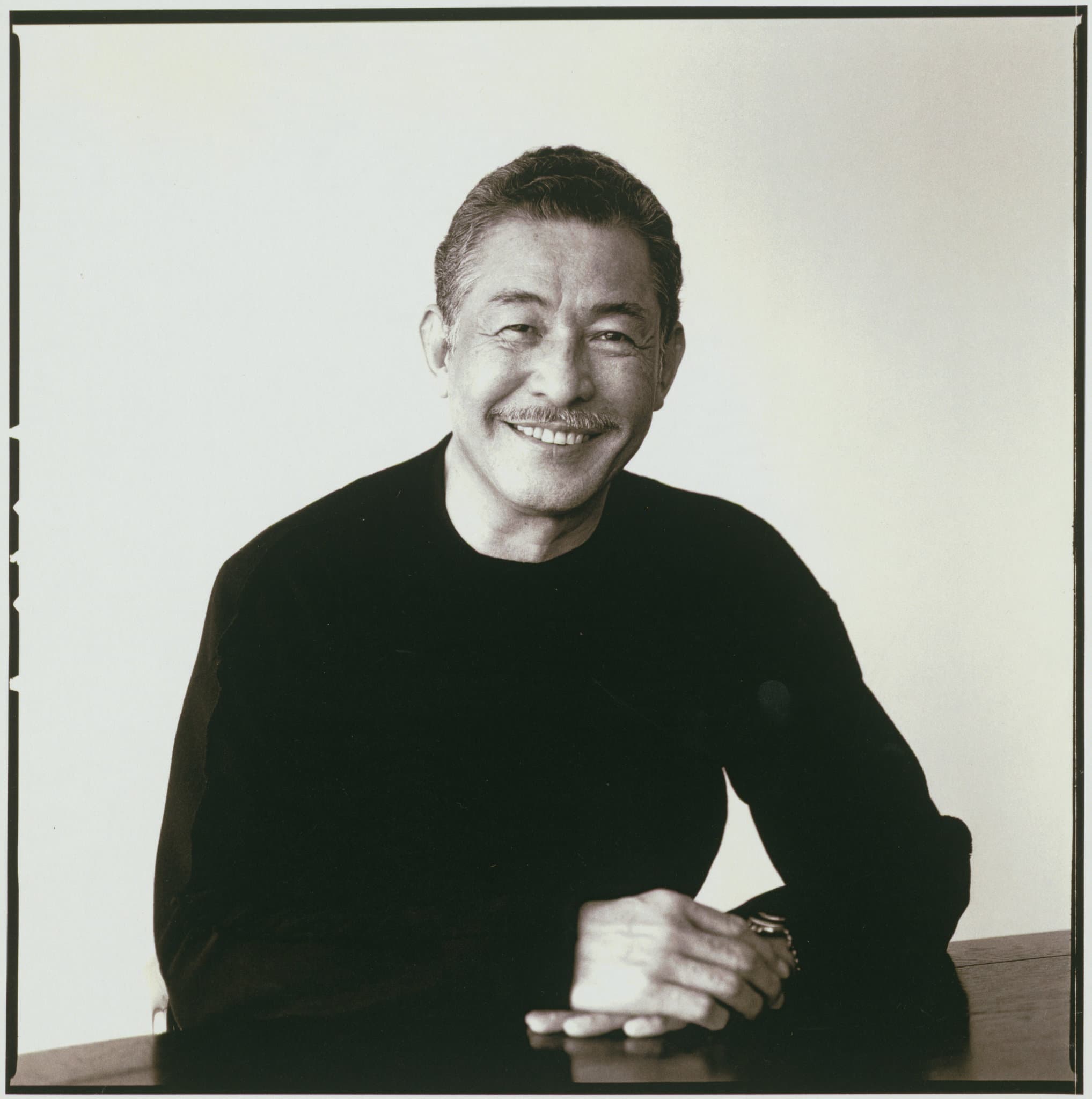

Issey Miyake

Fashion Designer, 84

Very few designers belong to that elusive group who have cultivated a signature that is instantly recognisable on a global scale, and has stood the test of time in the face of fashions fickle nature.

Issey Miyake (originally named Miyake Kazunaru) was born in Hiroshima in 1938, and survived injury from the atomic bomb dropped by the U.S. in 1945. Recounting to the New York Times In 2009, he revealed the experience caused him to gravitate towards clothing design – as a way to create, rather than destroy – and “because it is a creative format that is modern and optimistic”.

Driven by a keen interest in technology and the transformative nature of materials, Miyake seamlessly blended ideas from both the east and west to create a lane of his own making. Steadfastly experimenting with form and fabric his work was considered innovative and future-facing, especially for its time. Miyake’s early career spanned time in Paris, working for Hubert de Givenchy and Guy La Roche, and New York, where he met Andy Warhol.

His body of work encompassed concepts including ‘A-POC – A Piece of Cloth’ introduced in 1997, where he worked with textile engineer Dai Fujiwara on a knitting machine that would produce a stream of fabric, which could be cut and customised by the wearer, amplifying the idea of clothing for “the many rather than for the few” and minimising waste. His decade-long collaboration with photographer Irving Penn, who (sans influence from Miyake himself, who never attended any studio sessions) expertly captured the graphic energy, organic flow, and hyperbolic volume of each garment, and in the process redefined the way in which fashion was transformed into image. And his now infamous ‘Pleats Please’ line, which pioneered a new technique which reversed the production process, and instead saw the designer cut deliberately oversized shapes, which would then be fed through a heat-press, which would shrink them down and pleat them into the perfect size. First trialled as costumes designed for a performance by William Forsythe’s Frankfurt Ballet company in 1991, the designs are loved the world-over for their freedom (most pieces came without the need for fastenings) and ease (it can be rolled for travel and machine-washed) that they afford the wearer. The ‘Pleats Please Issey Miyake’ line launched in 1993 and has been the designer’s legacy and signature calling card, that is often imitated, but never truly replicated.

Seeing the value of collaboration across industries, Miyake’s project with Sony in 1981 led to the development of the late Steve Jobs iconic uniform of a black turtleneck (which Miyake later retired following the death of the Apple CEO). Tapped to design a jacket for the Sony corporations 35th anniversary, the final look consisted of a modular nylon jacket, whose sleeves could be detached to make a vest. During a visit to Sony, Jobs, enamoured by the idea sought out Miyake to create a uniform for himself (after trying to replicate the concept of an employee uniform, which mimicked that of Sony, fell flat), hence the over 100 turtlenecks that graced Jobs closet.

Achieving the rare feat of crossing over to the art world and becoming a beloved go-to designer for gallerists and collectors alike – of both his pleated clothing and Bao Bao bag – the designer himself did not want his clothing to be considered art, despite their propensity towards the sculptural and appearing on the cover of Artforum (specifically a rattan-vine body, resembling a glossy dismembered torso), he liked to work in a circular way, and once a piece was worn the process in-effect came full-circle.

Holding his own among the wave of Japanese designers who took the Paris runways by storm, and included Yohji Yamamoto, Rei Kawakubo, and Junya Watanabe, his enduring legacy will be that of bringing a visionary idea of Japanese fashion to the global masses, which was for the masses, embedding the idea of innovation and experimentation as a way to facilitate everyday ease and freedom of movement.

Manfred Thierry Mugler

Fashion and Costume Designer, 73

Manfred Thierry Mugler, was a designer whose avant-garde world was based on four key pillars – showmanship, the architecture of the anatomy, celebrating confident women, and embracing the infinite possibilities of the imagination.

Thierry Mugler, later to be known by his given name Manfred, embodied what it meant to sell sex as a powerful tool that the female of the species could wield to her advantage. Long before the idea of camp filtered its way into mainstream fashion (it was the theme of 2019’s Met Gala and subsequent exhibition ‘Camp: Notes on Fashion’), and became commercialised, Mugler was an arbiter of the genre through the medium of fashion. Exaggerating and contorting the female form with the help of corsetry underpinning and moulding techniques, he etched out a particular maximalist niche for himself that was never compromising, safe, or boring.

Born in 1948 in Strasbourg, France his obsession with performance started early as he took up ballet, before joining the National Rhine Opera at 14, moving to Paris age 20. Building his namesake label, throughout the 1970s, Mugler always had an eye on the future, while incorporating the otherworldly – a number of his couture creations resembled undersea creatures hybridised with fancy feathers, cyborg-like armour reminiscent of space-age robots, and his first foray into the world of fragrance was named Angel.

The 1980s, through to the 90s, saw Mugler honing how to put on a show, with some being attended by close to 6000 guests, his theatrical presentations were the hot ticket every season. Most significant was his spring summer 1997 ‘Les Insectes’ haute couture collection which featured oversized butterfly motifs emerging from dresses and bug-eyed headwear. Spring summer 1992’s ‘Les Cowboys’ ready-to-wear collection spawned the now infamous motorcycle-inspired bustier, comprised of metal and plexiglass and complete with handlebars and rear-view mirrors. It has also been immortalised in pop music history being worn for George Michael’s Too Funky music video, as well as by Beyonce for the promotion of her ‘I Am..” tour. And autumn winter 1995-96 ‘20th Anniversary’ haute couture show, staged at Paris’s Cirque d’Hiver (a historical location, which had previously hosted circuses, dressage exhibitions, and Turkish wrestling) starred Tippi Hedren, Jerry Hall, Naomi Campbell, and Kate Moss, with an unbridled performance from James Brown. Revisiting a number of his greatest hits the show was a celebration of his fembot creations, the ‘Venus’ dress’ (worn by Cardi B at the 2019 Grammy Awards), and wasp-waisted power suits.

Following his 2002 departure from his label, he expanded into the world of costume design in 2009, where he teamed with Beyonce to dress her then alter-ego Sasha Fierce for her “I Am..” world tour, emphasising the singers desire to create a duality between “being a woman and a warrior”. Also taking on the role of Creative Advisor for the tour, he developed a 71-piece collection, while overseeing choreography, lighting, and production.

Perhaps the perfect modern muse for his aesthetic, Mugler was selected by Kim Kardashian as her designer of choice for her Met Gala look in 2019, coming out of retirement he designed a latex naked dress. Prior to his death earlier this year, the designer attended the opening of the Paris leg of his major retrospective exhibition tour titled ‘Thierry Mugler: Couturissime’ at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs. Now in Brooklyn, New York until May 2023, the show retraces the designer’s career, from 1973 to 2014.

Hanae Mori

Japanese Couturier, 96

Hanae Mori, born Hanae Fujii in Yoshika, southwestern Japan in 1926, was part of a wave of designers who emerged from post-war Japan to have a global impact with their east-meet-west design sensibilities. She started her career as a dressmaker when she opened her atelier in 1951 in Shinjuku Tokyo, catering to the wives of American G.I.s.

In 1977, Mori was the first Asian female couturier to be admitted into the Chambre Syndicale de la haute Couture (after being inspired to start her practice, following a visit to Coco Chanel’s salon in Paris), showing alongside the likes of Christian Dior, Givenchy, and Valentino that same year. Turning her hand to ready-to-wear she debuted her first collection in New York in 1965. Winning a loyal fanbase for her take on conservative western tailoring, women sought out her well-made designs in colour-combinations that were made contemporary through the melding of influences from her heritage, such as obi belts and kimono sleeve details. Spanning categories including mens and womens day and eveningwear, accessories, and childrens clothing, she later expanded into interiors and fragrance. Her designs were sold in Neiman Marcus, Bergdorf Goodman, Henri Bendel, and Saks Fifth Avenue department stores, as well as a store in the Waldorf Astoria in 1970. Crossing over to Europe and Paris’s Avenue Montaigne in 1977, when the brand reported sales of $70 million, she maintained her 30 boutiques in Japan, and a wholesale line that was carried in over 100 Japanese stores.

Appealing to women in her home country, who were newly entering the workforce post-war, Mori provided a new way-to-wear the office uniform, as well as reinventing dressing for all occasions. Her handle on occasion dressing, saw her maintain an esteemed client list of many of high society’s key players – from former First Lady Nancy Reagan to Sophia Loren, Princess Masako, and Princess Grace of Monaco.

As with many of the designers, the chance to design for a range of adjacent industries came calling, with her expertise being applied to costumes for film (including Japanese movies of the 1950s and 60s), and Japan Airlines flight attendant uniforms. She later worked with the Puccini opera’s ‘Madame Butterfly’ in 1985, Rudolf Nureyev’s ‘Cinderella’ production in Paris in 1986, and for Richard Strauss’s ‘Elektra’ opera in 1996 at the Salzburg Music Festival. Her experience designing uniforms also saw her outfit the Japanese team at the 1992 Barcelona Olympics.

The symbol of the butterfly (which earned her the nickname ‘Madame Butterfly’ in western media) became her houses’s signature across distinctive prints in silk and chiffon, that were rendered in western silhouettes – bringing the Japanese culture to the West – and were used to mark the finale looks of her last show in 2004.

This year has been no less poignant in the names, many who were front-row fixtures, cultural trailblazers, and multi-hyphenate storytellers who took their final bow in 2022.