Politics/Fashion

For God’s Sake – Stand Them Down

Faced with the white supremacist organization the Proud Boys adopting their black and yellow colorway, Fred Perry did something the President of the United States spectacularly failed to do: they released an unequivocal, unambiguous statement disavowing the group.

‘Fred Perry does not support and is in no way affiliated with the Proud Boys,’ the brand announced via their website, going on to say it was ‘incredibly frustrating’ for them that the group had appropriated their design and ‘subverted our Laurel Wreath to their own ends’.

This is not the first time the brand has had to deal with the frustration of racist groups adopting their clothing – and perhaps their experience of dealing with such instances over the decades has helped to harden their response. To understand why cultural misappropriation has plagued the company for so long, we first need to look at the subtleties and shifting allegiances of British youth sub-genres of the late 20th century.

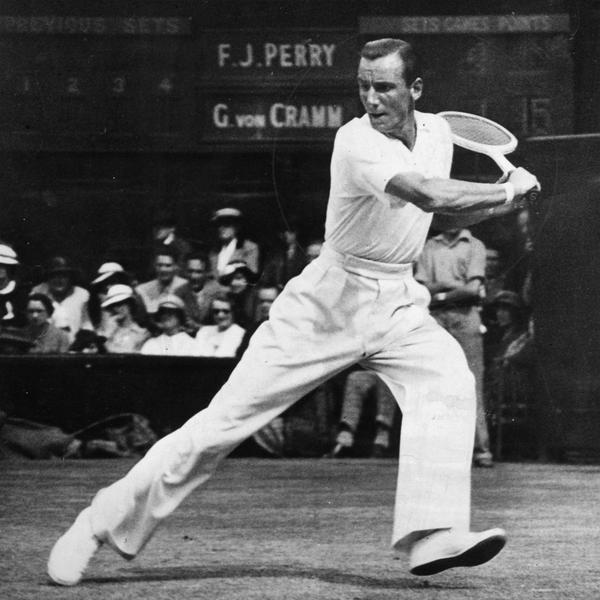

Having first put his name and laurel wreath logo to his own sweatband design in the 1940s, British Wimbledon champion Fred Perry soon found a market for his tennis attire, launching his first shirt in 1952. (An interesting footnote: he moved to the US and became a naturalized citizen in 1938, and was drafted into the USAF during World War II – in other words he literally fought against the Nazis and the idea of racial supremacy).

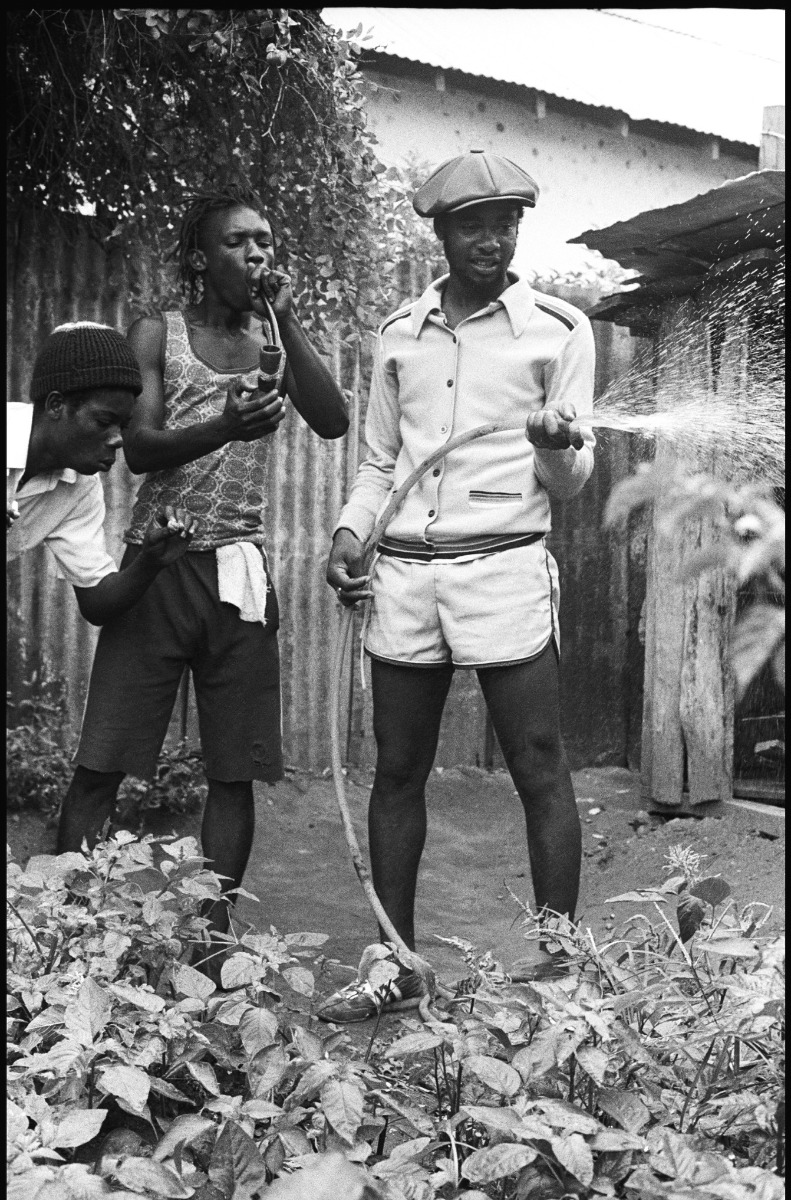

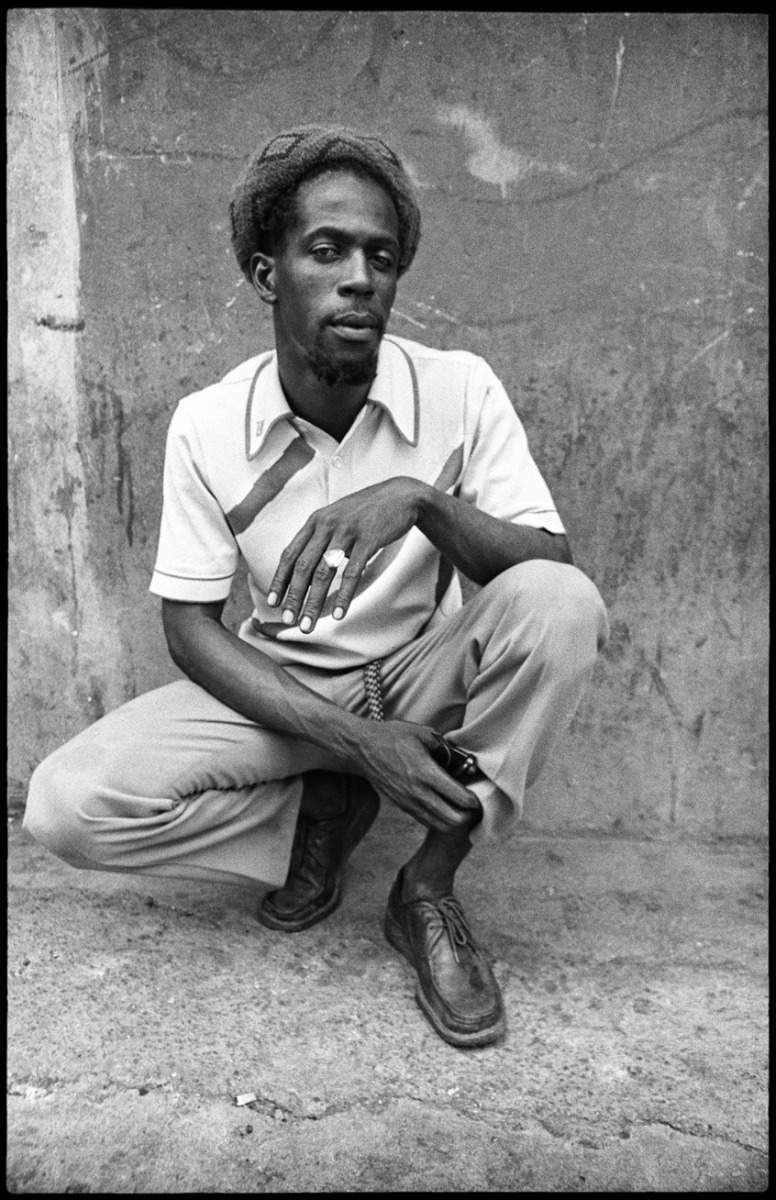

Perry’s shirts became popular with the mod scene of the 1960s – typically white Britons with a liking for black American soul music and Italian modernism. The distinct dress code of mod fed into other youth movements – notably the skinheads. Here, again, some historical context is needed. Skinheads are typically associated today with extremist right-wing politics and racist attitudes. For the original skinheads of the 1960s, however, this is the ultimate affront – given that they were followers of Jamaica’s emerging reggae stars. Indeed, their entire look – skinny jeans, Fred Perry shirts and close-cropped hair – was modeled on West Indian style.

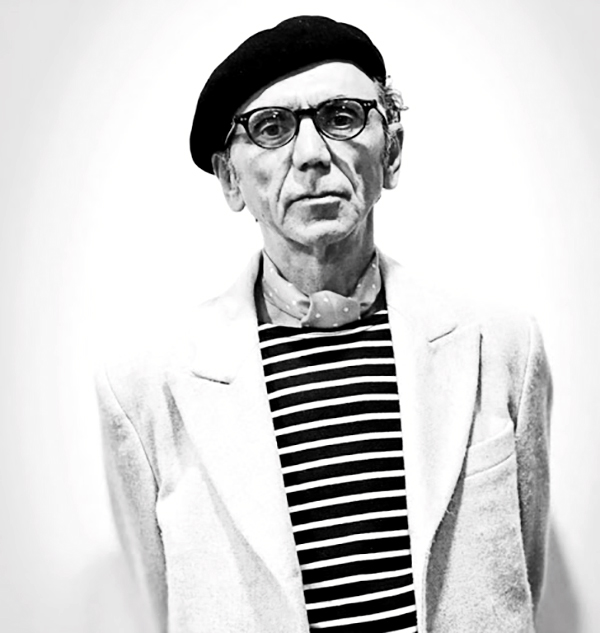

Kevin Rowland, founder of the 1980s pop group Dexys Midnight Runners, was one of those early adopters. ‘We used to chant “Skinhead, skinhead!” at school,’ he told me when we met in a café in London’s East End to discuss how fashion has shaped his life.

Back then it was a look inspired by reggae: it was inspired by the black kids. But that second generation of skinheads, who came around 1979 – they were numbskulls. They were without style, just awful. Even the way they dressed, they got it so wrong, whereas the original look came completely out of mod, it was a continuation of that.

— Kevin Rowland, founder of Dexys Midnight Runners

‘I’m not trying to sound cool, but it was a very sophisticated culture,’ Rowland continued. ‘You couldn’t buy the records, they weren’t in the charts; there were only two shops in London where you could buy the clothes. Remember this was 1969. We were listening to reggae in the youth clubs while the only black culture the middle classes knew was Jimi Hendrix.’

Fred Perry – as a man and as a brand – has always been visible in opposing racism and intolerance, accentuating instead its many positive associations with diversity and inclusivity throughout British popular culture.

It has long been the uniform of ska and 2 Tone, for instance: the genre spearheaded by groundbreaking multicultural acts of the 1980s including The Specials, The [English] Beat, and The Selector. Indeed, when The Specials reformed recently, Fred Perry was the lead sponsors of their tour, releasing an exclusive collection dedicated to the band.

In case the penny hasn’t dropped, Fred Perry elucidate further on their website: ‘The Fred Perry shirt is a piece of British subcultural uniform, adopted by various groups of people who recognise their own values in what it stands for. We are proud of its lineage and what the Laurel Wreath has represented for over 65 years: inclusivity, diversity and independence.’

In response to the Proud Boys (a group whose values are very different to those referred to above), Fred Perry has taken the unprecedented measure of discontinuing their black/yellow shirt across Northern America with immediate effect. Whilst this is a swift and bold move, there are some who feel it was a miss-step.

I was disappointed by the pulling (removal of the shirts in North America) to be honest. There was an opportunity to promote a positive message about the fundamental impact black culture has had on the brand – i.e. if it wasn’t for black/rudeboy culture, Fred Perry would probably not exist.

– Former Senior Fred Perry marketer

Whilst acknowledging the validity of that reaction, we feel Fred Perry still deserve praise for backing their words with actions – and making it crystal clear which side they stand with. We approached Fred Perry for a reaction, but understandably they preferred not to add fuel to the fire in any official capacity, other than reiterating one simple message, “Frankly, we can’t put our disapproval in better words than our Chairman did when questioned in 2017.” Going on to quote Fred Perry Chairman John Flynn, “Fred was the son of a working class socialist MP who became a world tennis champion at a time when tennis was an elitist sport. He started a business with a Jewish businessman from Eastern Europe. It’s a shame we even have to answer questions like this. No, we don’t support the ideals or the group that you speak of. It is counter to our beliefs and the people we work with”.

The real question – and this has been asked many times before – is how well-intentioned fans of the brand should respond.

Speaking personally, the black and yellow colorway has long been a favourite of mine. Should I ‘cease and desist’ – or should I wear it proudly (in the right sense of the word) as a symbol of solidarity with those targeted by right-wing groups? To paraphrase Kevin Rowland: thankfully, not living in Portland, it doesn’t apply. But it feels like a defeat to let them win.

Perhaps the solution lies in a two-pronged strategy: in the short term, deny access to the wrong audience and sue anyone using your trademarks inappropriately (as Fred Perry is doing against the Proud Boys).

But, secondly, in the words of Janelle Monae – focus on ‘Liberation, elevation, education’…