Ahead of the Spring-Summer 2022 Season, Fashion Faces an Altered Reality

By Long Nguyen

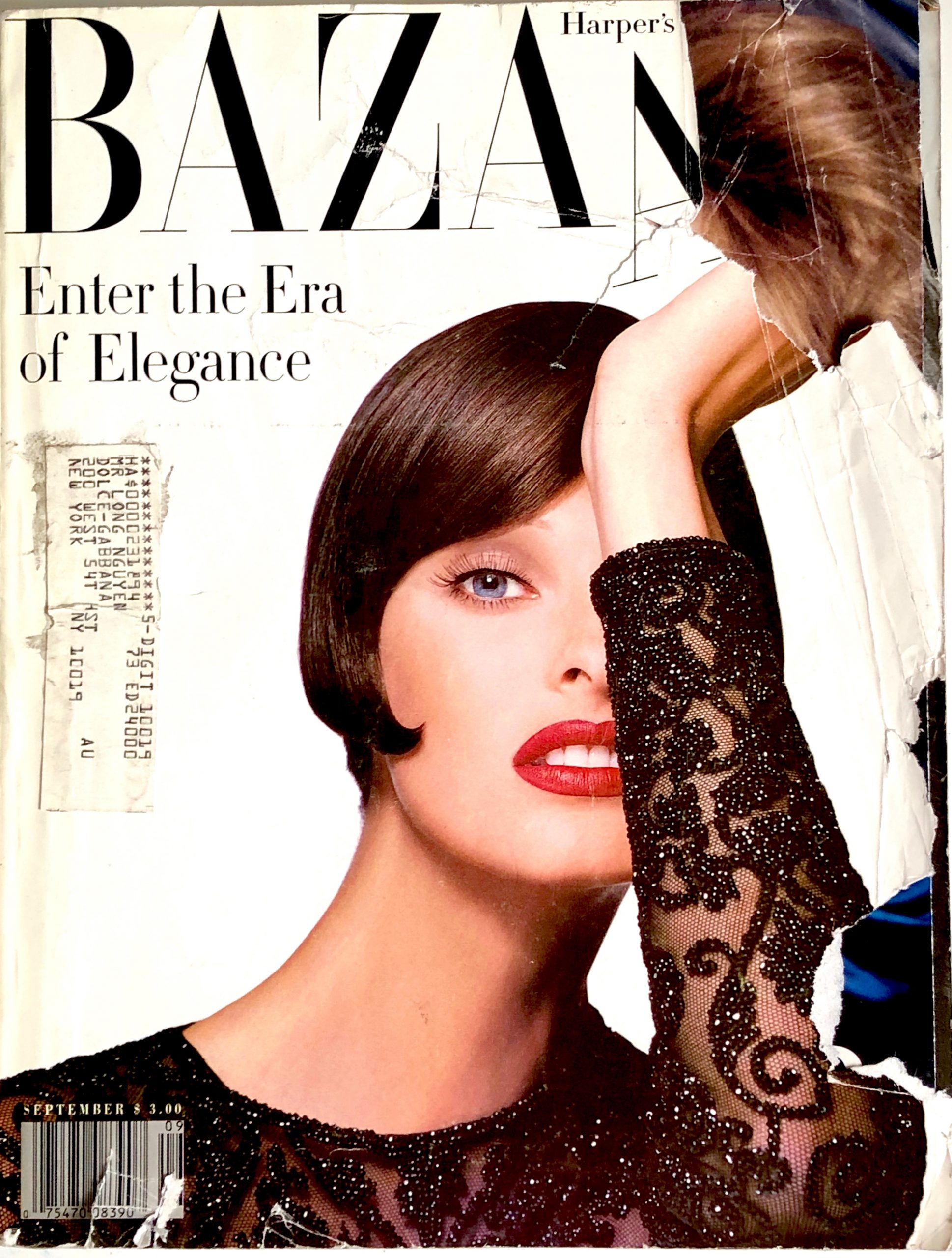

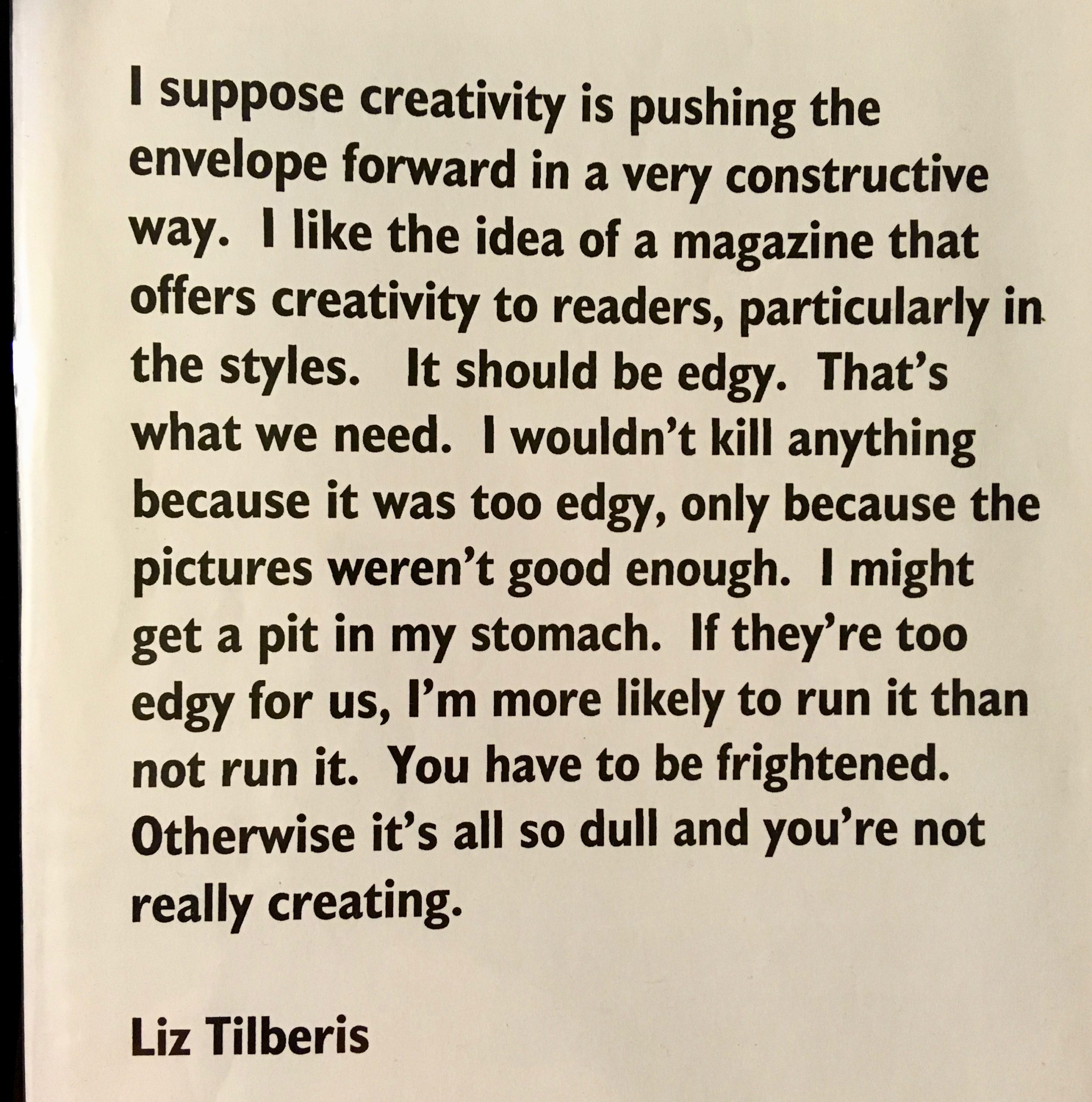

Around this time in the heatwave of late August to early September just before Labor Day in 1992, the fashion world finally saw the anxiously awaited arrival to the newsstands of the September issue of Harper’s Bazaar under the leadership of Liz Tilberis, appointed as editor-in-chief in early January 1992 with the mission of creating a brand new creative magazine launching in then considered the biggest magazine issue of the year.

Tilberis did not disappoint. Her September 1992 issue featured the super-model Linda Evangelista in a black sheer embroidered crew neck Donna Karan bodysuit photographed by Patrick Demarchelier against a stark white backdrop. Her left hand covered nearly half of her face. The only tagline was ‘Enter the Era of Elegance .’ The only gimmick was the letter A in Bazaar, slightly dropping downward on Evangelista’s palm.

In that distant analog era, the September 1992 Bazaar issue, an embodiment of fashion and the rising power of fashion almost three decades ago, ushered an epoch of hyper creativity in the 1990s, a period when youth composed and dictated the rebellious vocabulary of fashion. Fashion designers had gut then as they took daring risks to propel their brand forward but never sacrificed the high dose creative quotient, pushing their aesthetics far beyond the confines of the fashion industry to popular culture.

Then, it wasn’t just super creativity in fashion alone, but music, art, and cinema experienced a similar trajectory. Underground and local music burst onto the mainstream, altering what music videos, T.V., and radio played on air.

From 1992 to the end of the twentieth century, fashion was a cult system with many tribes subscribing to particular styles. Fashion, then, was less about grabbing the power of attention than a cinema projection of desires and transformations made possible by clothes. Fashion, then, had a powerful voice coupled with a definitive verdict of clothes rather than lumbering forward season after season.

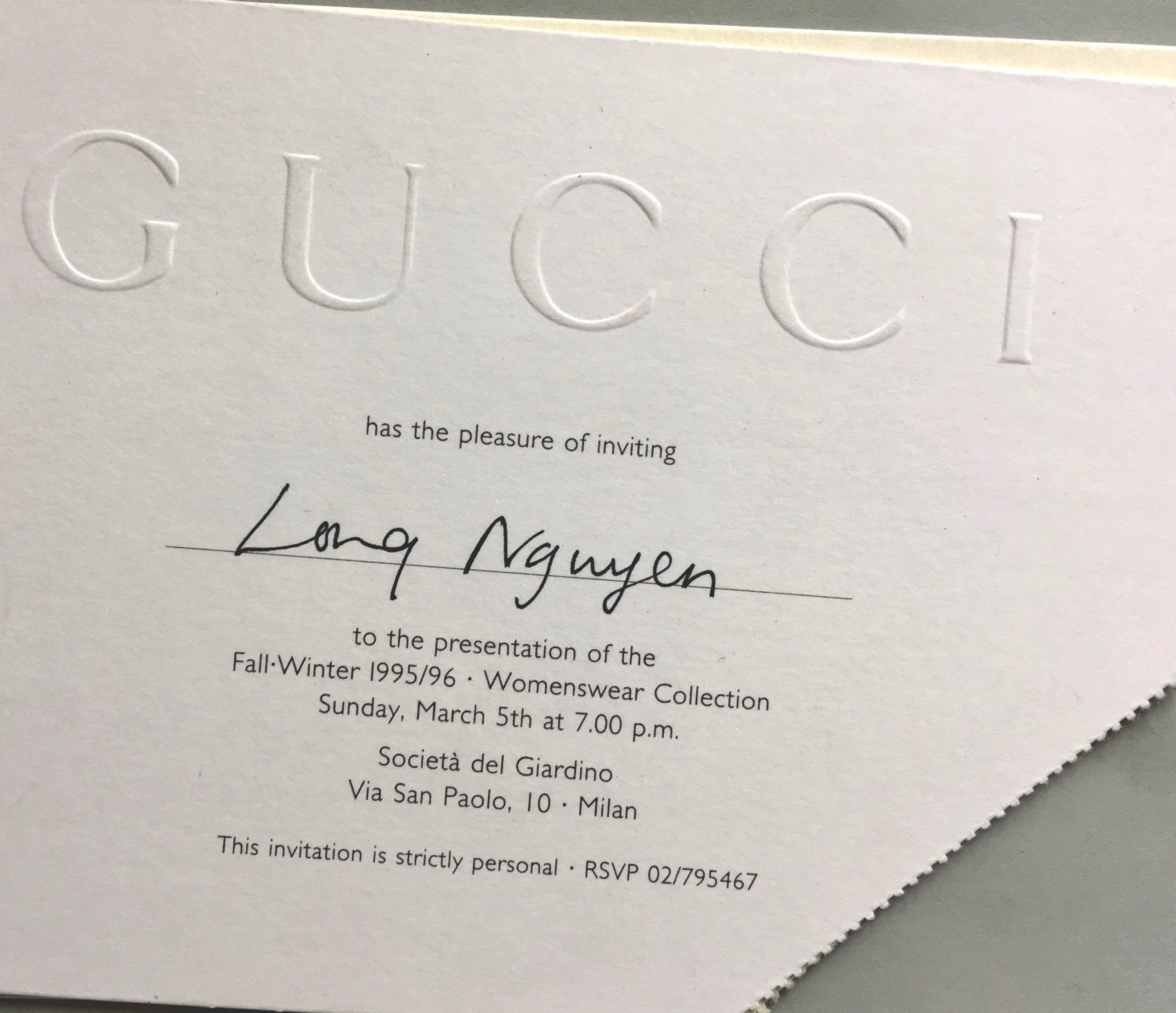

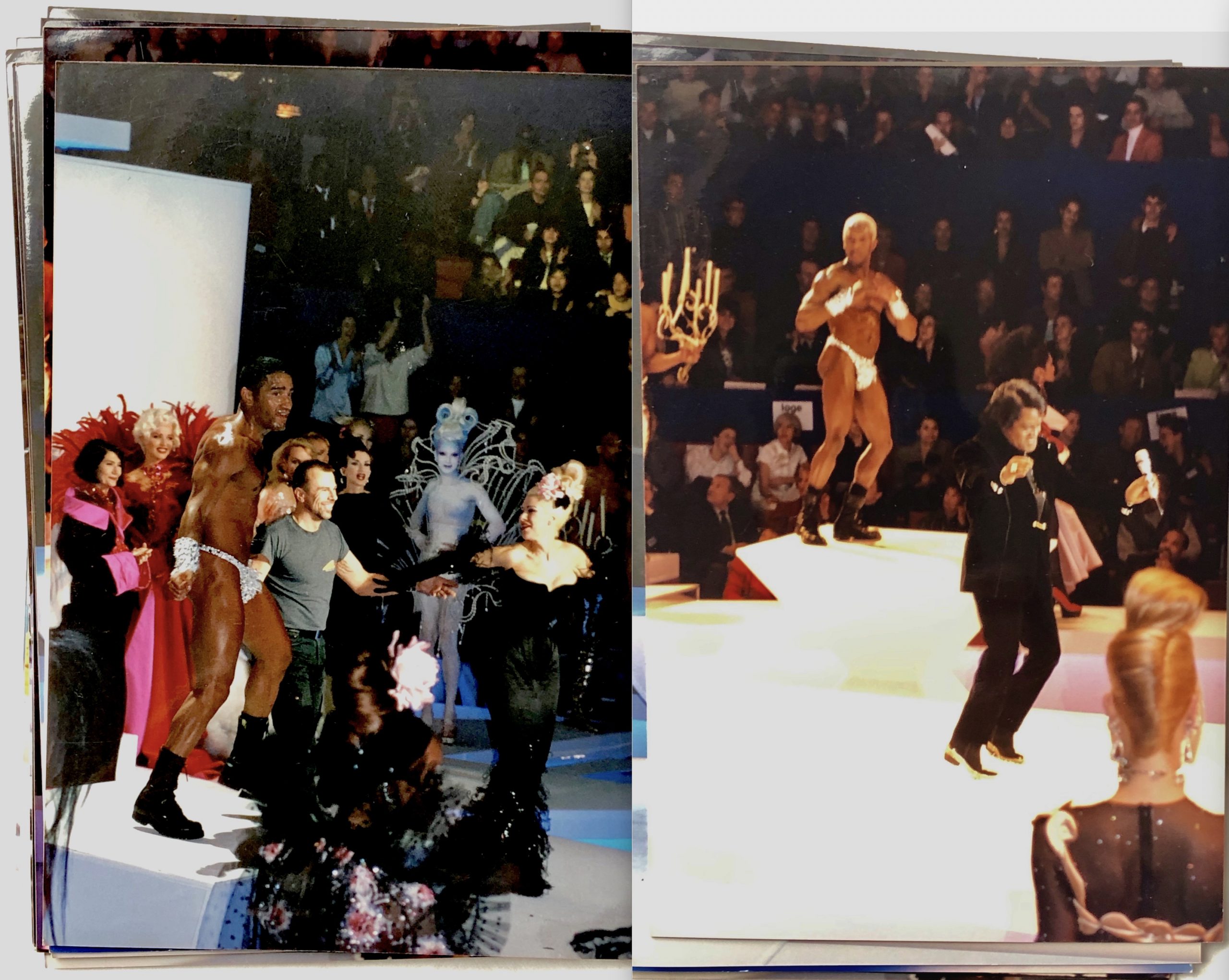

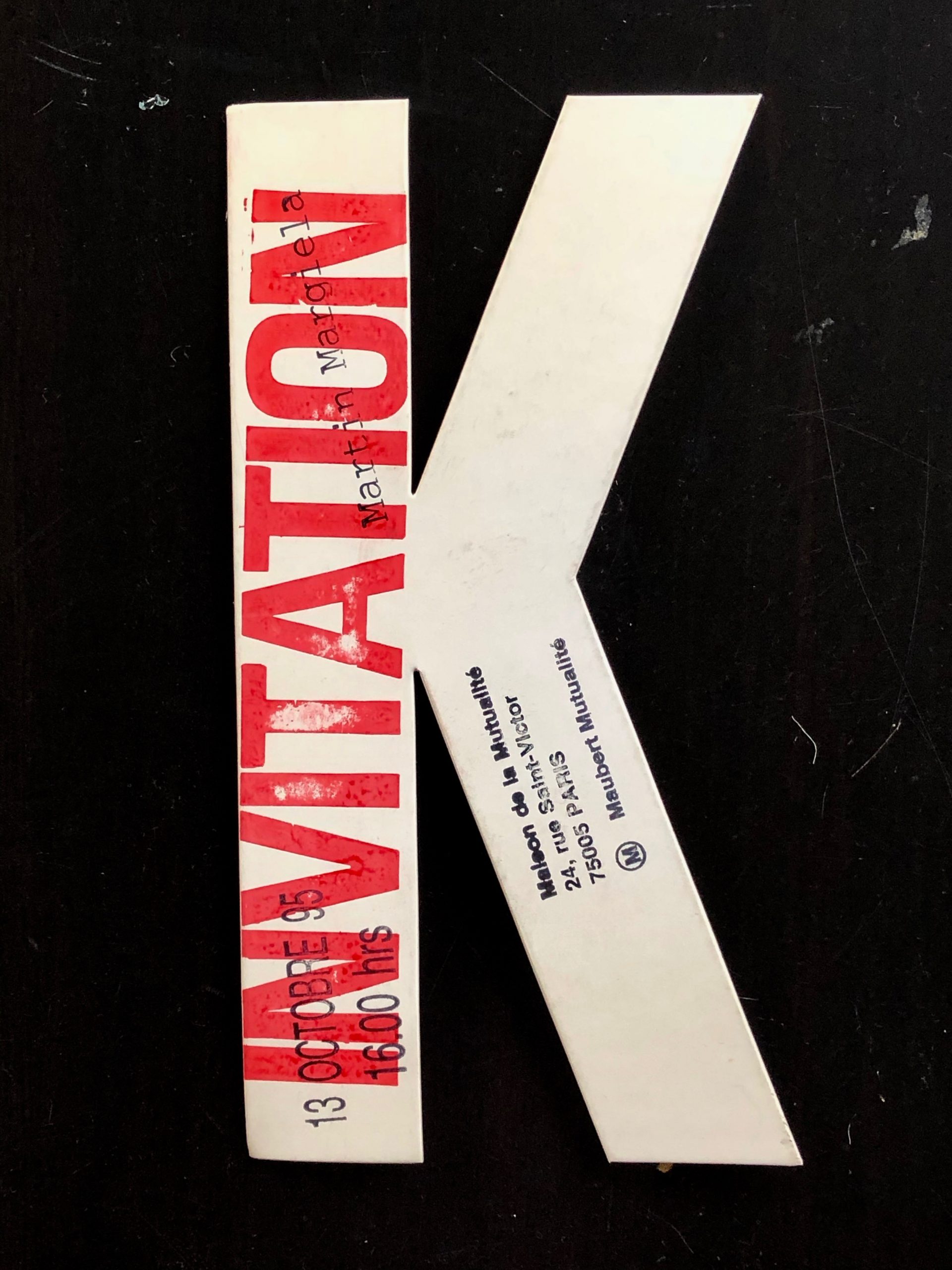

In early March 1995, Tom Ford’s broke in a big way with his Fall 1995 Gucci collection doused in the 70s sexiness that Madonna wore Ford’s Gucci blue silk shirt and velvet pants to the MTV Video Music Awards late August 1995. (Back then, music videos were a prime source of creativity for musicians.) At the Cirque d’hiver in Paris, Thierry Mugler presented his extravaganza hour-long 20th Anniversary show for Fall 1995 that was nothing short of a once-in-a-lifetime explosion of fearless fashion with extraordinary crafted sculptural garments. In October 1995, Martin Margiela showed Spring 1996 his trompe l’oeil and superb tailoring on all masked models at Maison de la mutualité conference center in a continuance to stir the archaic fashion system.

Gucci Fall-Winter 1995-1996

Thierry Mugler Fall 1995 20th Anniversary

Marin Margiela Spring 1996

Madonna in Gucci Fall 1995 MTV Video Music Awards

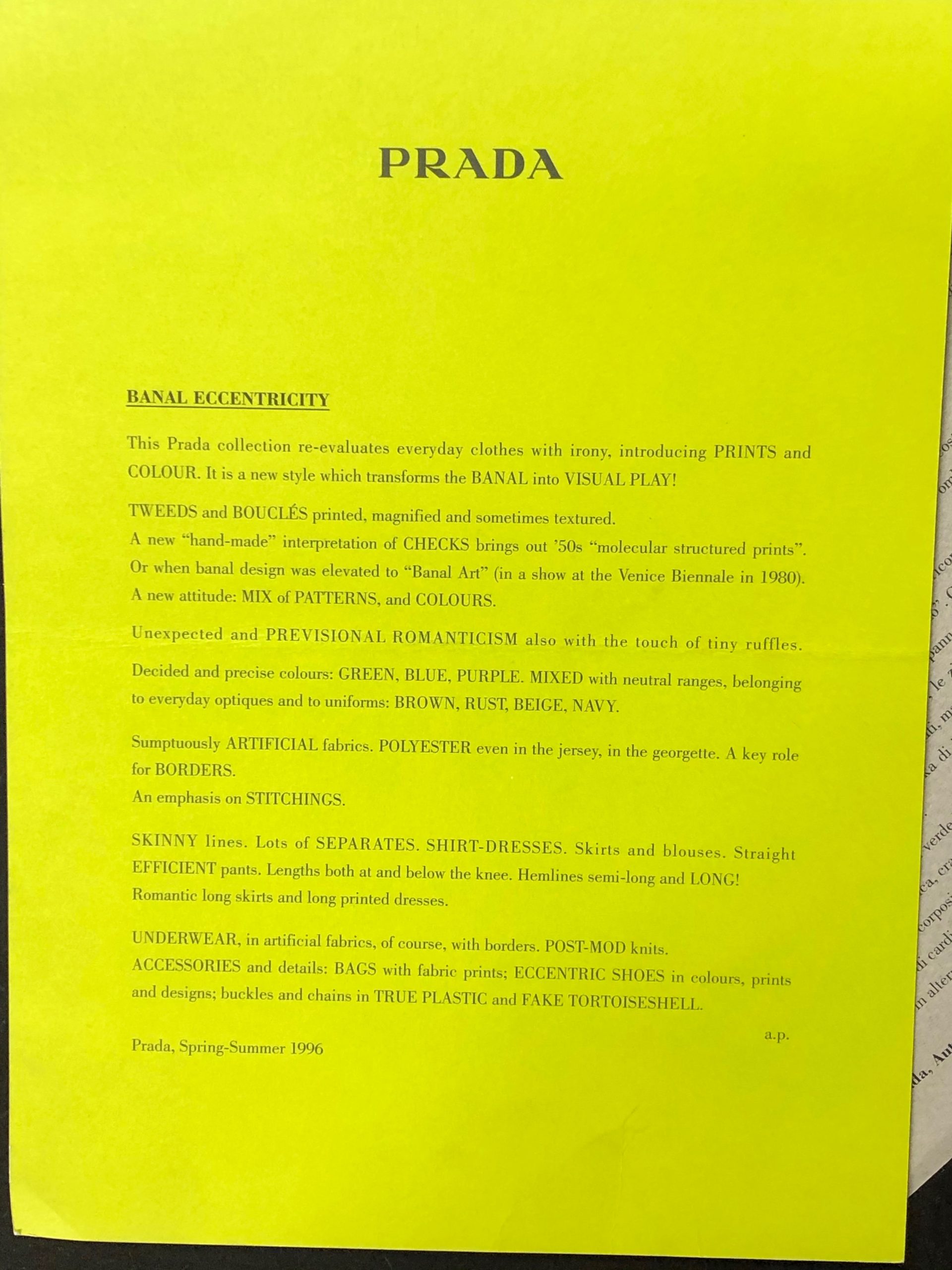

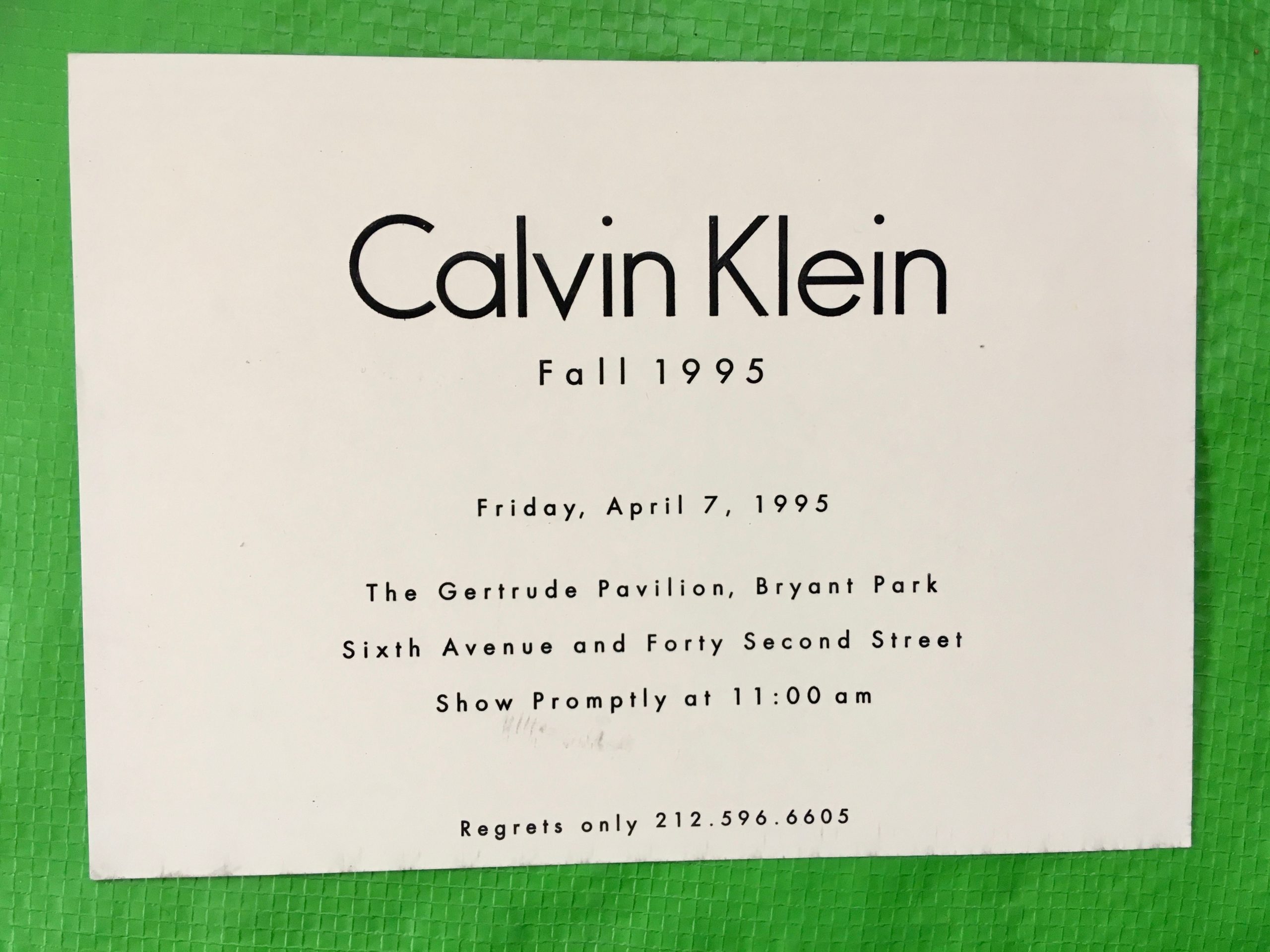

In September 1995 in Milano, Miuccia Prada’s ‘banal eccentricity’ Spring 1996 collection brought her art version of ugly chic to the forefront of fashion and strengthened her ready-to-wear as must-see-must-have collections. In April 1995, at the Seventh on Sixth tents in Bryan Park, Calvin Klein cemented his capture of the pop cultural pulse as Kate Moss opened his sleek monochrome show and earlier the Obsession fragrance. The infamous ‘kiddie porn’ CK Calvin Klein Jeans fall 1995 ad campaign canceled before it ran in global glossies and billboards firmed Klein’s capture of the pop culture moment.

Prada Spring 1996 ‘Banal Eccentricity”

Calvin Klein Fall 1995

Kate Moss in Calvin Klein Fall 1995

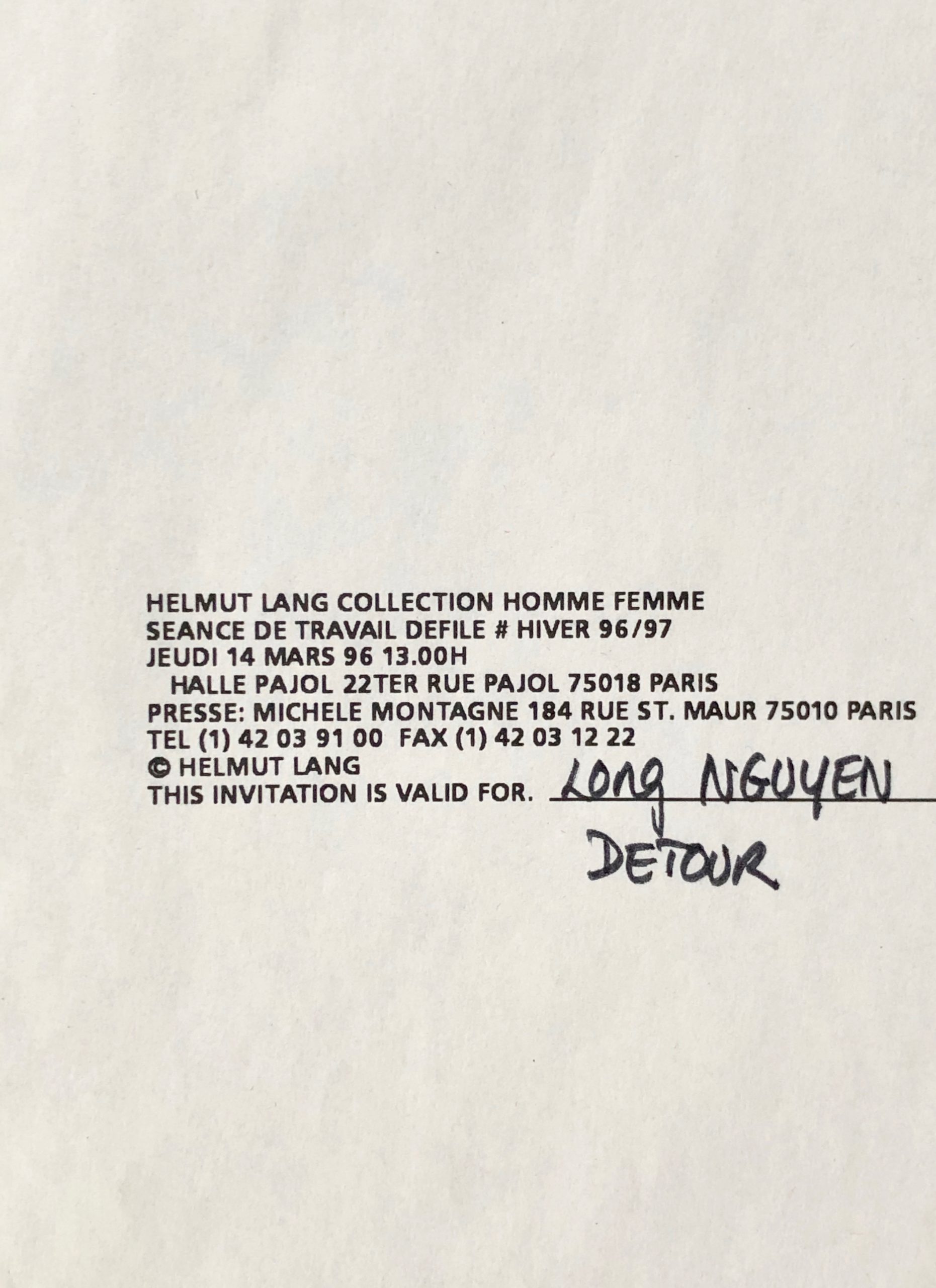

In March 1996, in a railway yard in northern Paris, Helmut Lang’s Amber Valletta, Kate Moss, and Naomi Campbell marched fashion towards a new definition of elegance for the young tribes in the post-punk decade. Audiences at that Lang show got gold thermal wrap due to the unusual freeze.

Helmut Lang Fall 1996

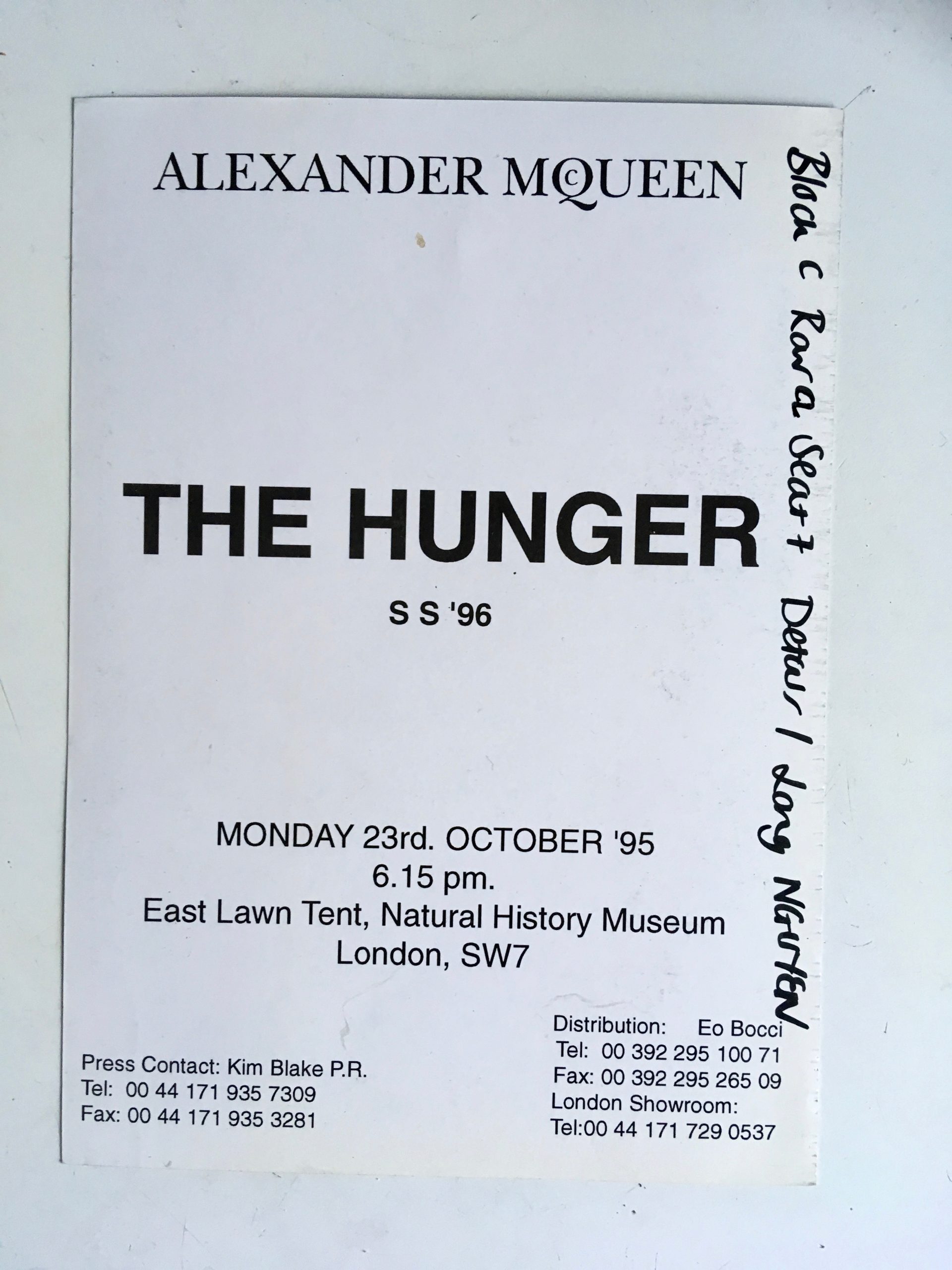

Alexander McQueen Spring 1996

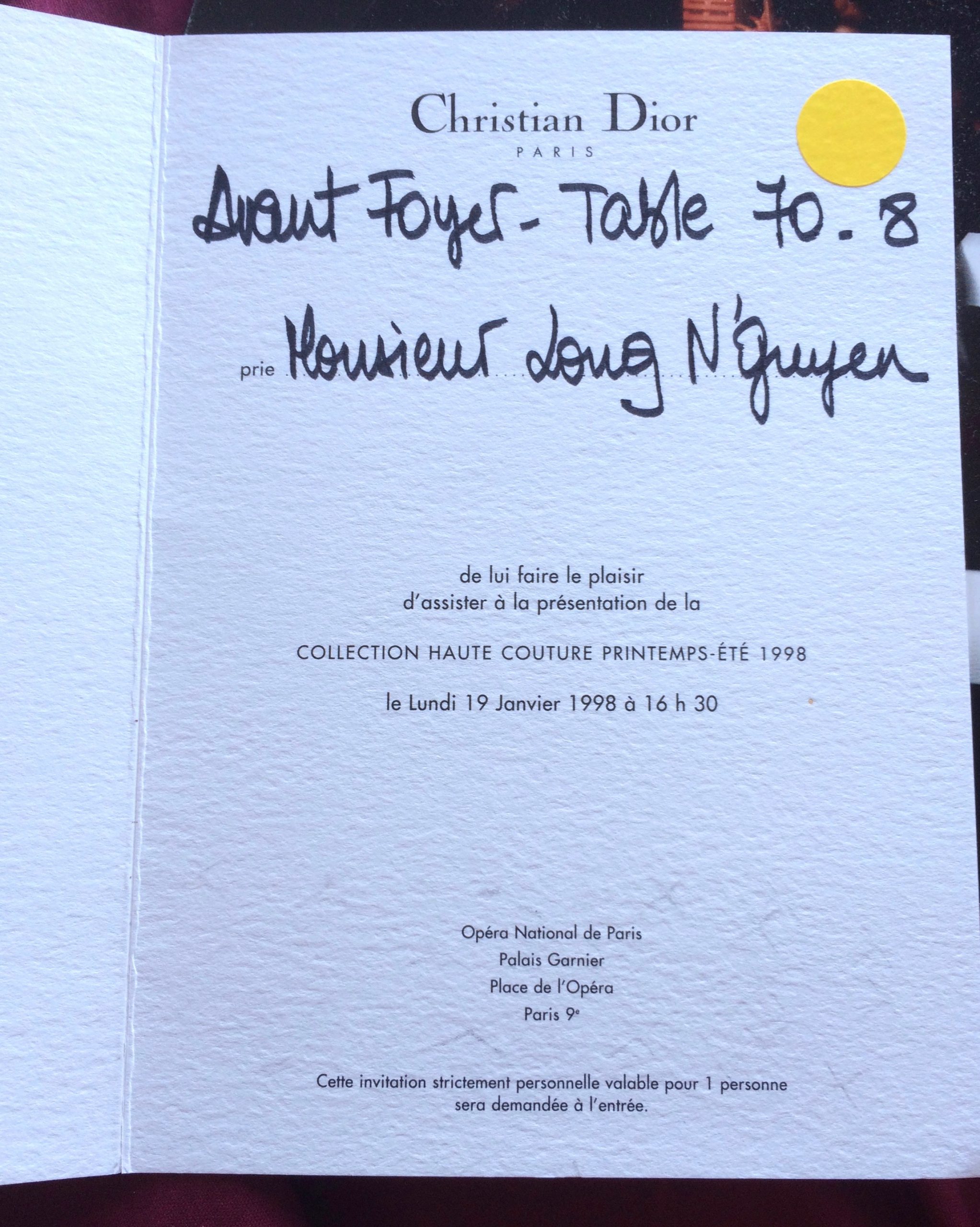

Dior Haute Couture Spring 1998

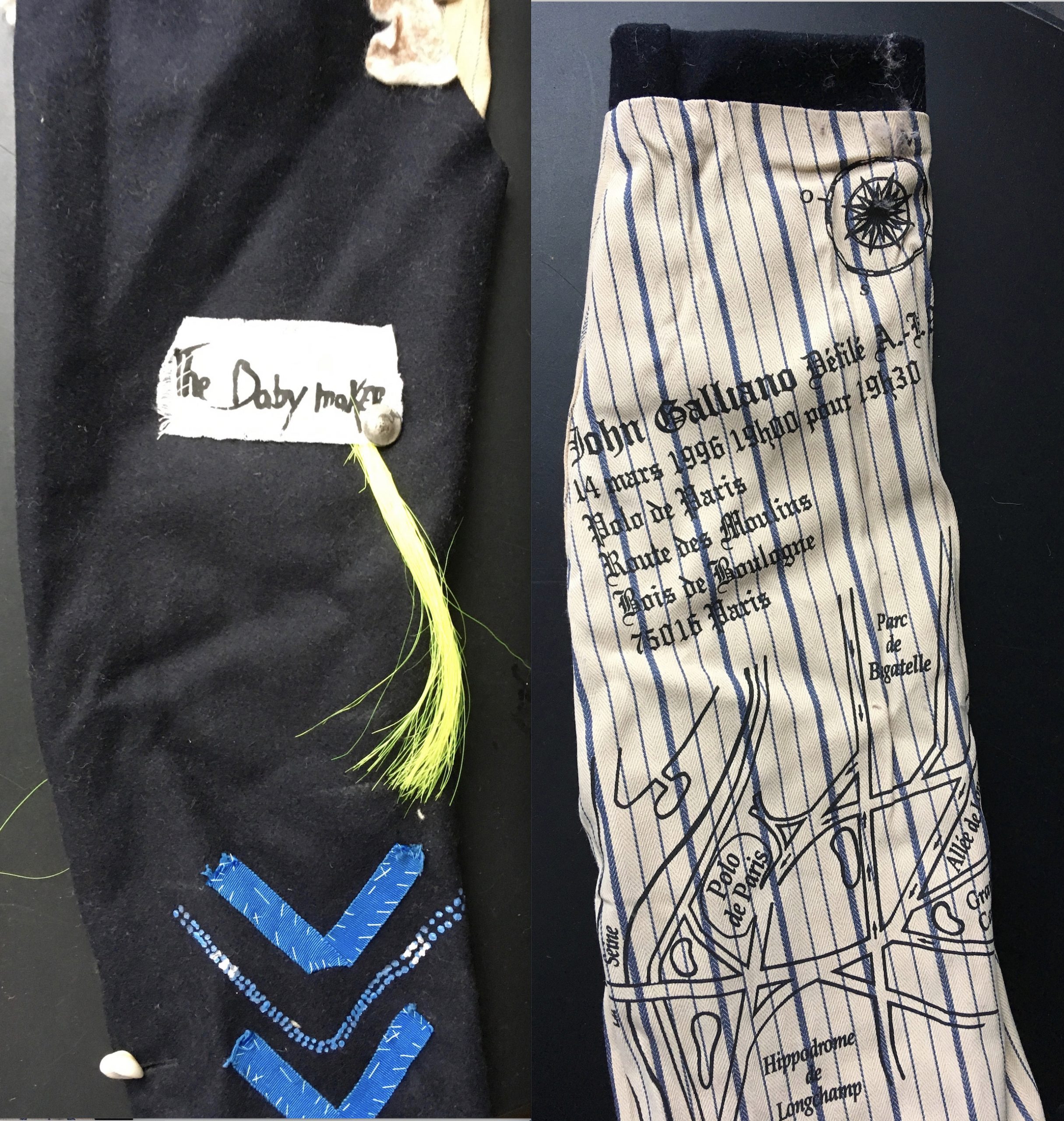

John Galliano Fall 1996

Gaultier Paris Spring-Summer 1997

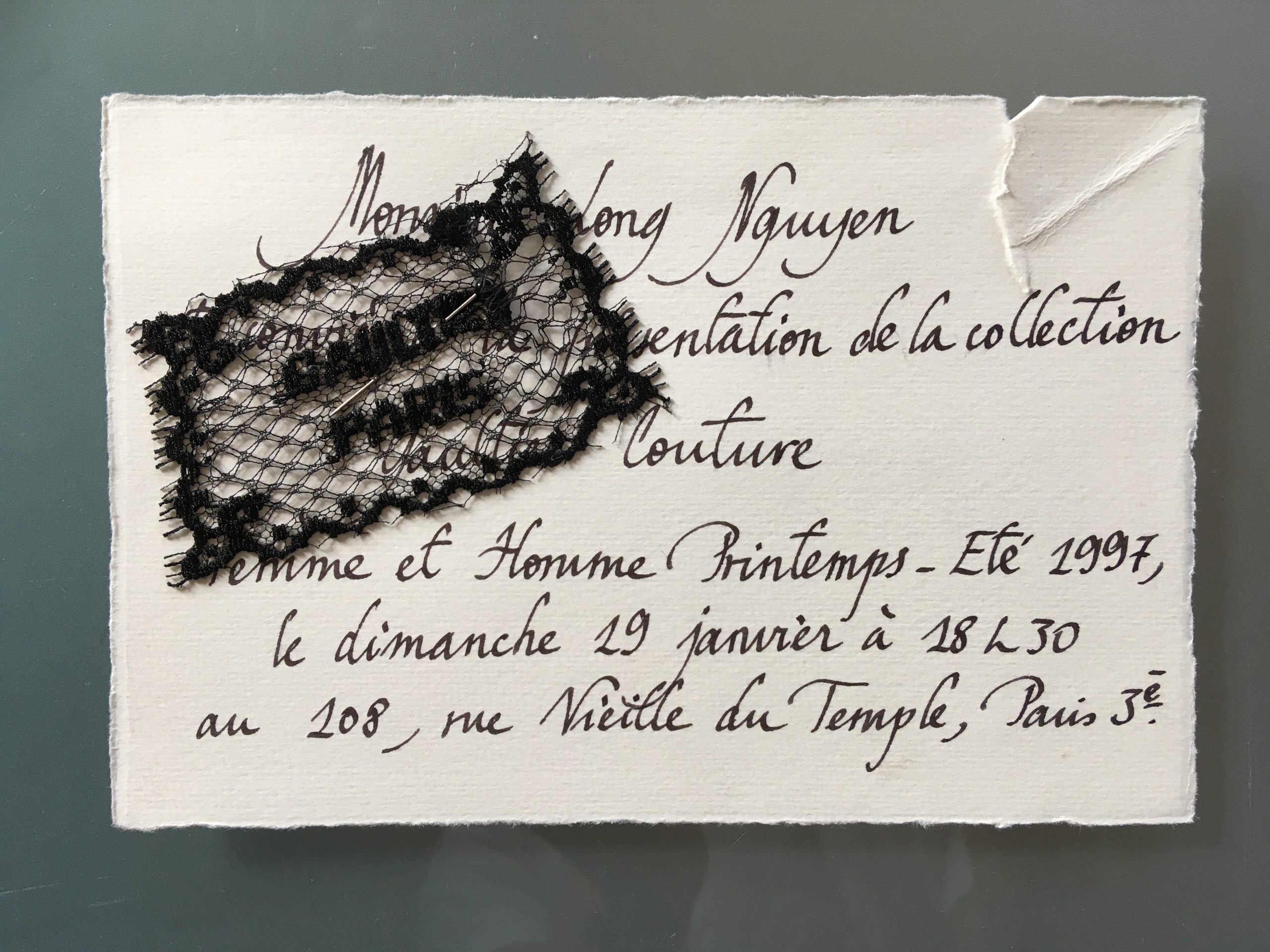

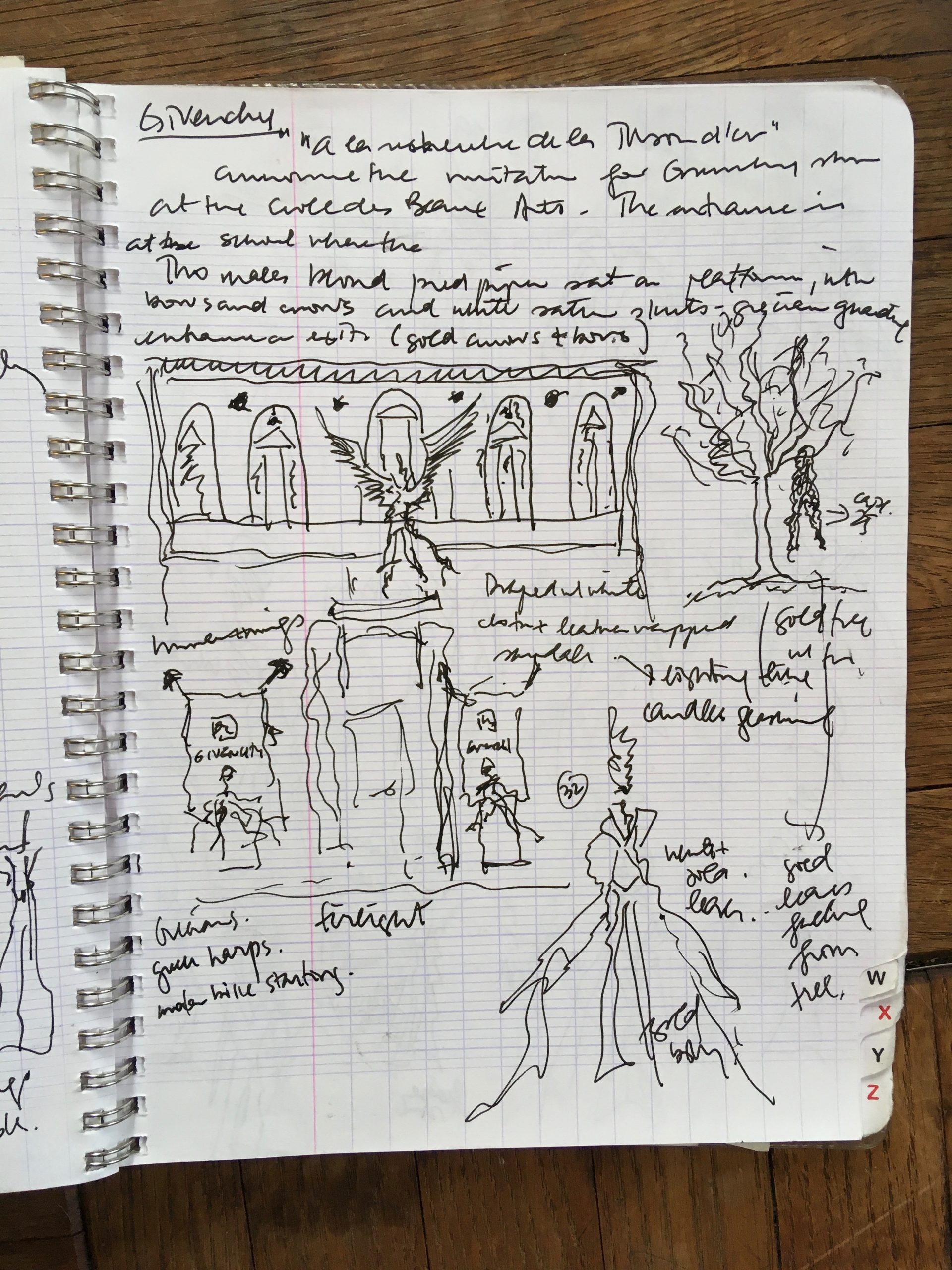

Notes from Givenchy Haute Couture Spring-Summer 1997

15 GIVENCHY HAUTE COUTURE SPRING 1998

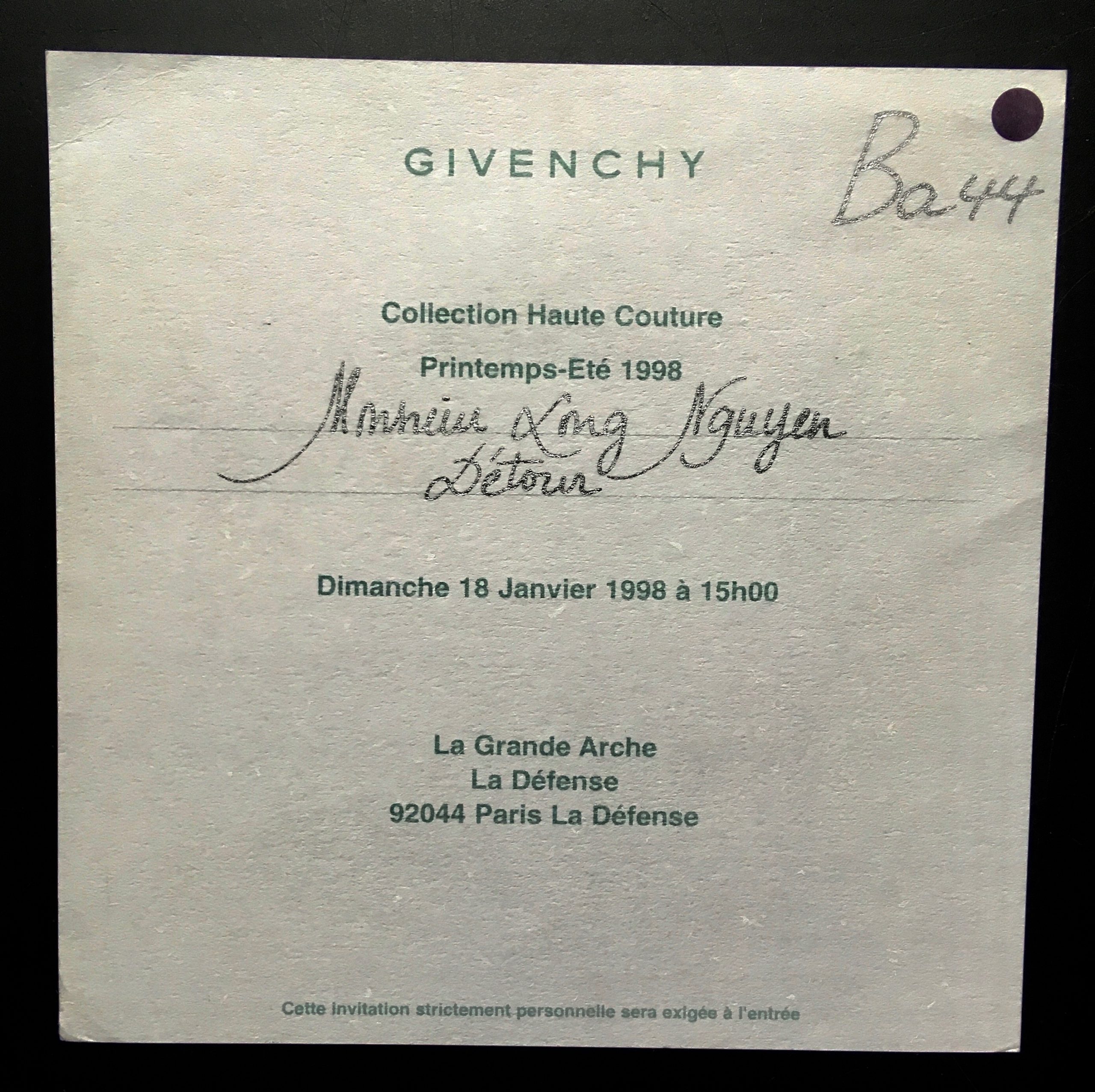

In January 1997, Jean-Paul Gaultier launched his first imaginative and innovative Spring 1997 couture collection. Alexander McQueen’s debuted Givenchy haute couture show at the École des beaux-arts and John Galliano at Le Grande Hôtel, ushering new eras for Givenchy and Dior. Fresh from their lyrical and experimental work in London merging raw emotions with outrage, John Galliano and Alexander McQueen decamped to Paris, bringing their fabulous imaginative fashion and master tailoring to Dior and Givenchy.

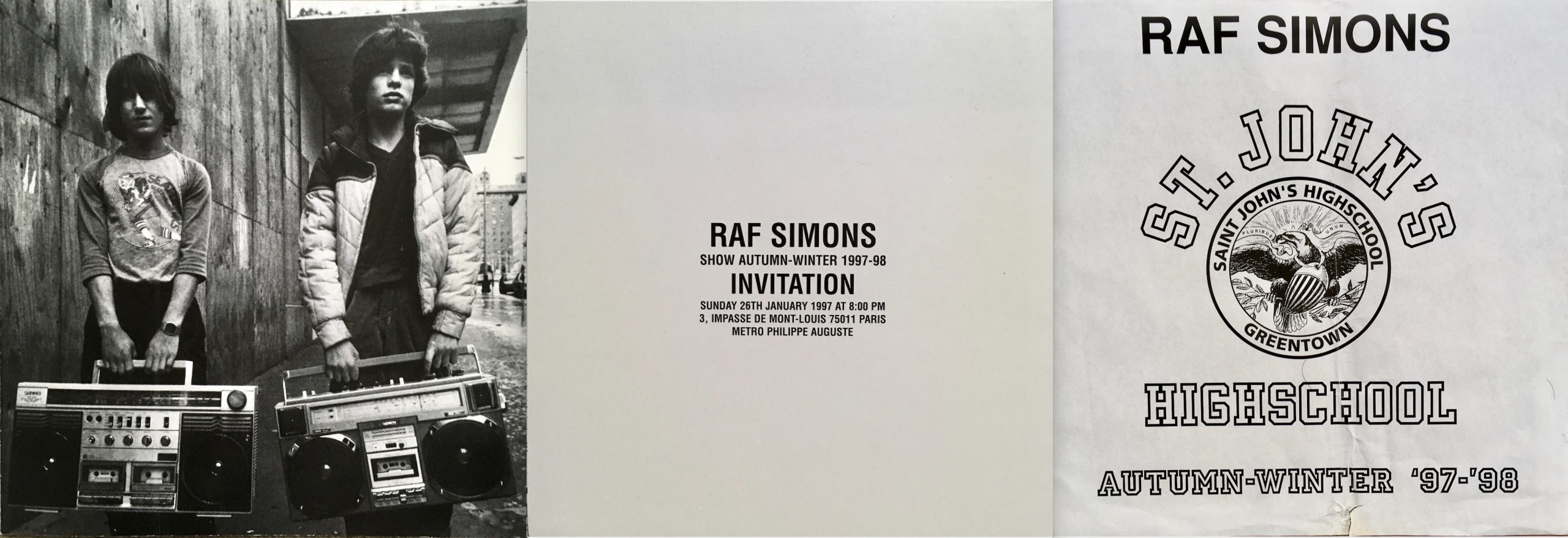

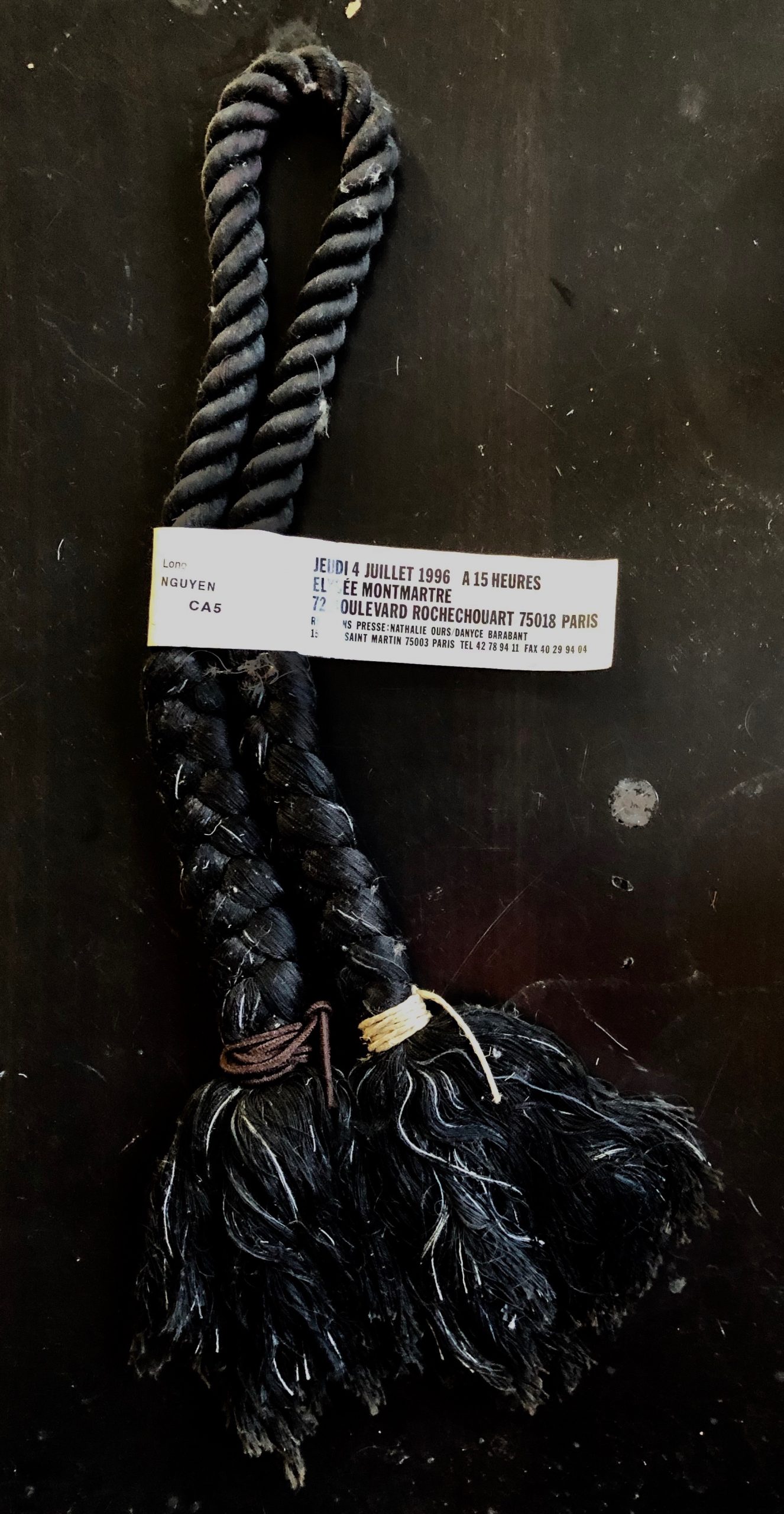

Raf Simons Fall-Winter 1997-1998

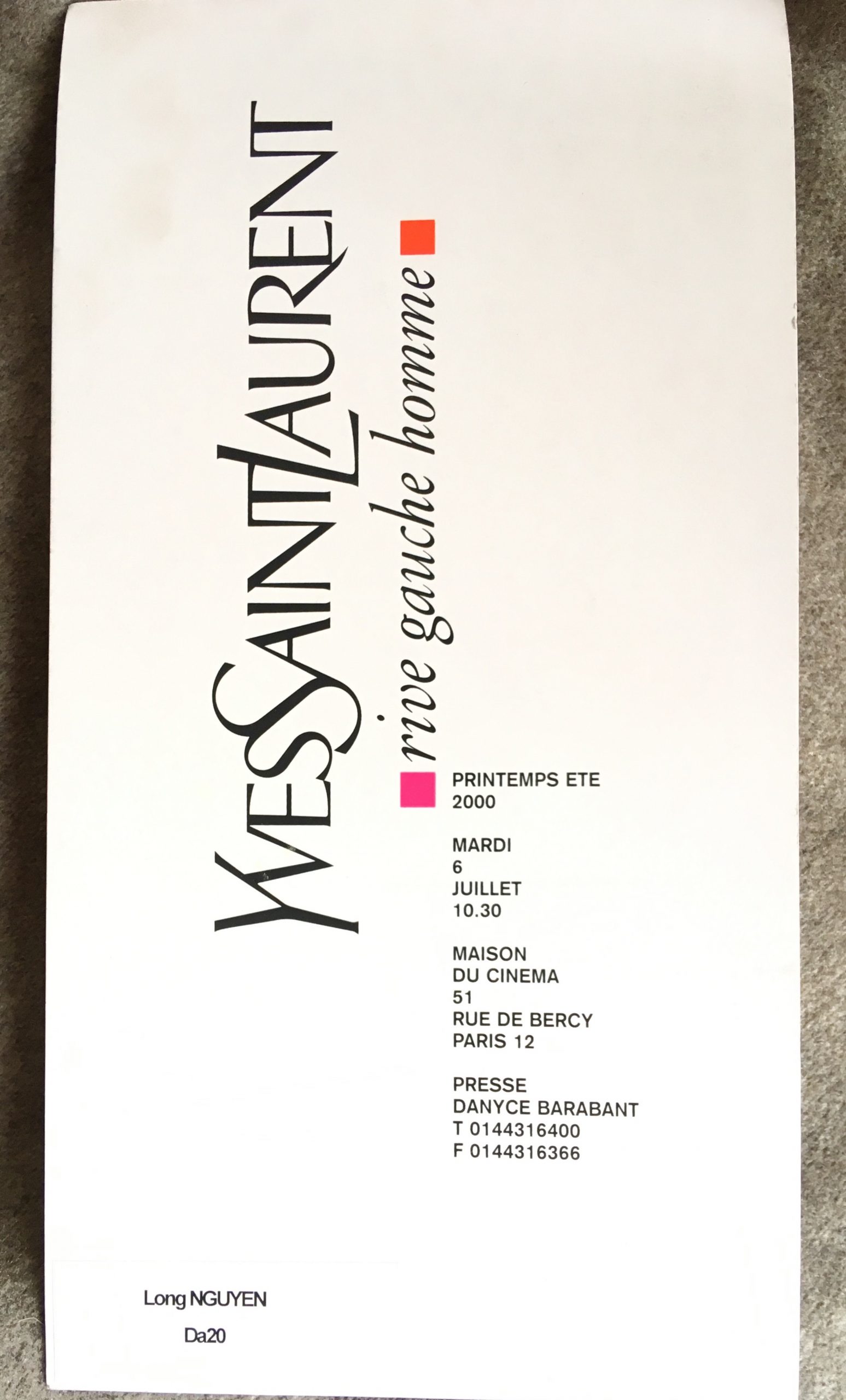

Yves Saint Lauren Rive Gauche Homme Spring 2000

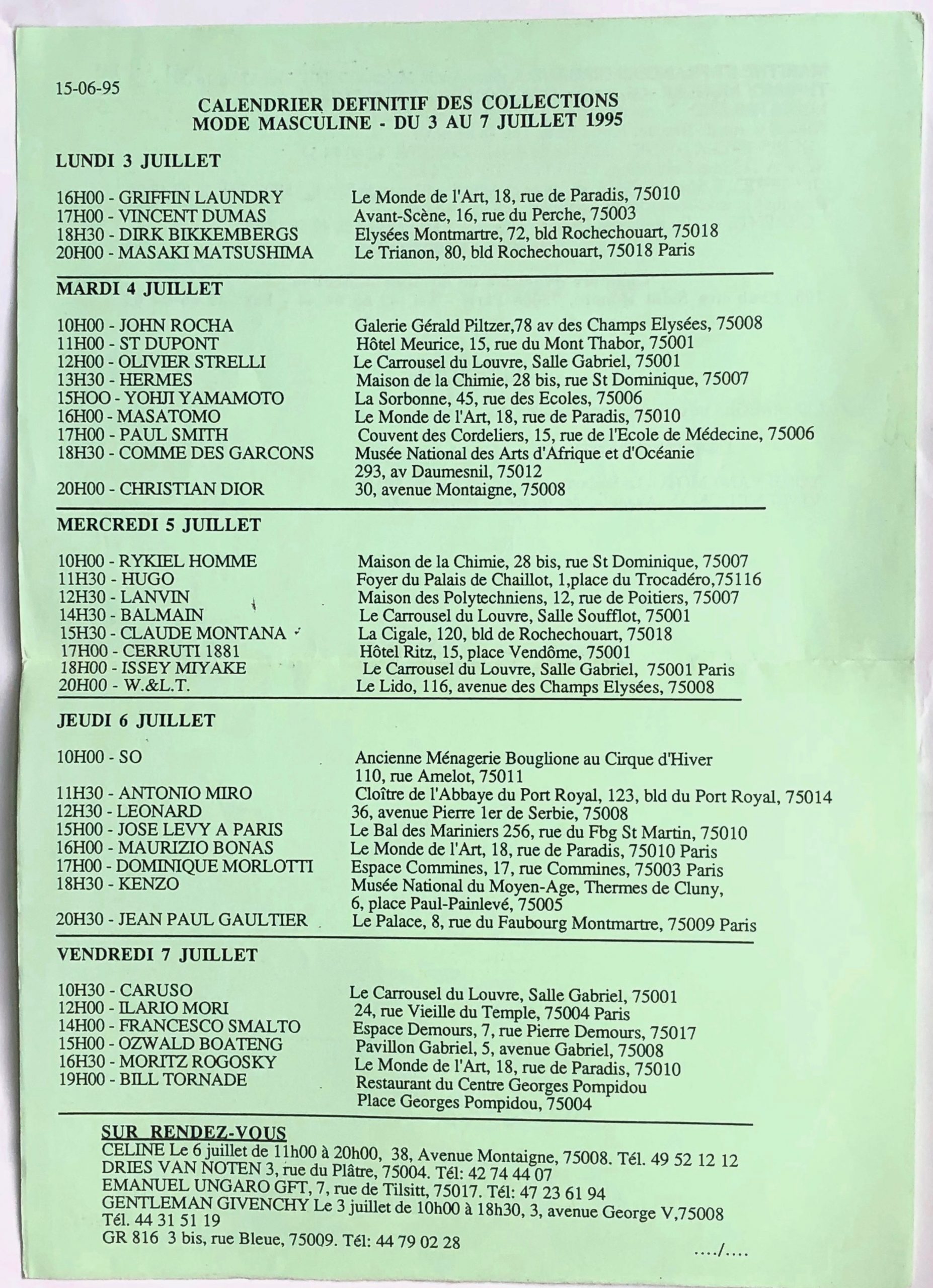

Raf Simons, a young Belgian designer, showed in Paris inside a garage near the Bastille for the first time. Simons’ high school kids, all came in a bus from Antwerp, changed the idea of men’s fashion and changed the clothes. At the Maison de la chimie in Paris, a little-known designer Hedi Slimane presented a small show for Yves Saint Laurent Rive Gauche Homme’s fall 1997 collection recalibrating young men’s elegance.

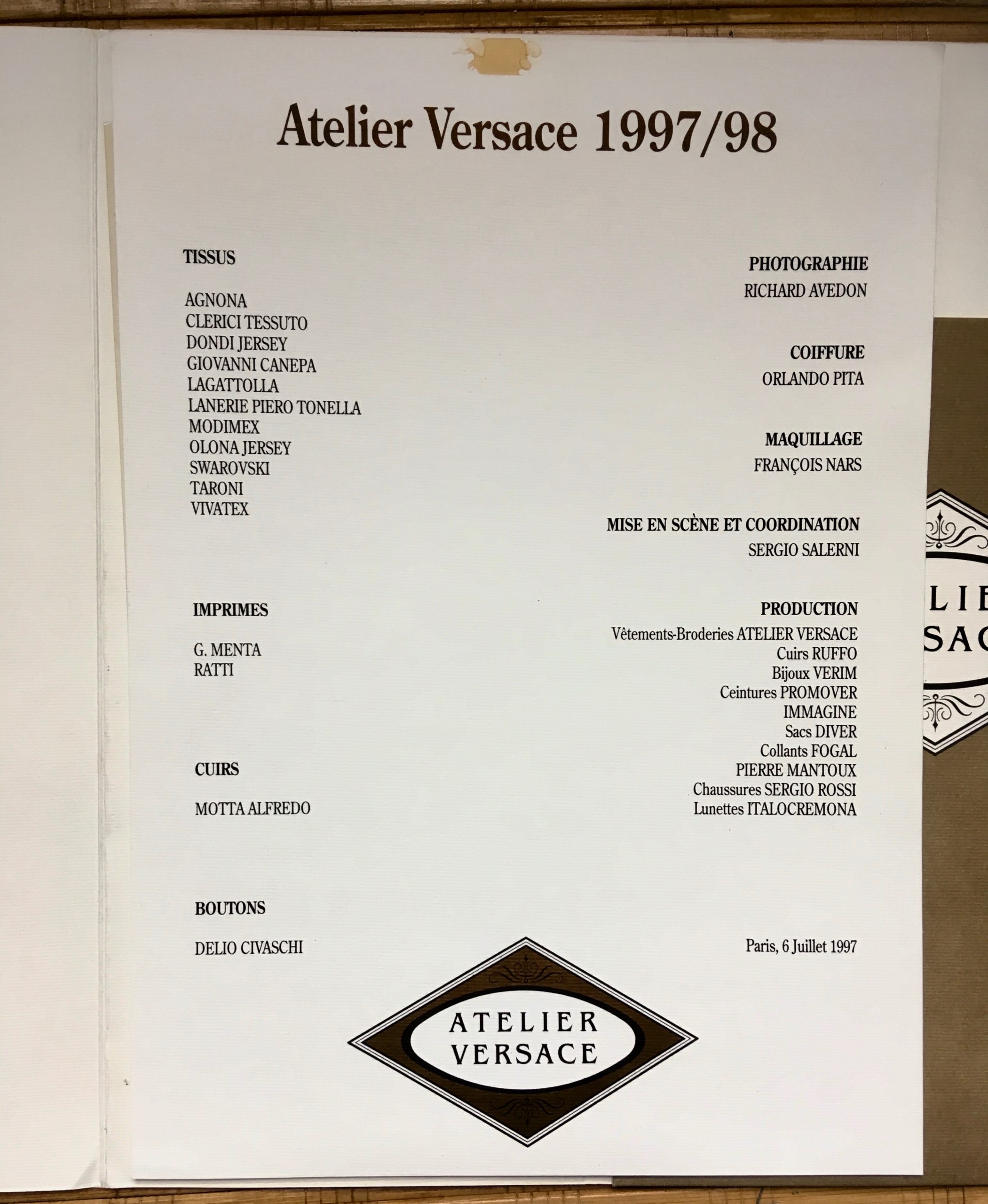

Gianni Versace Atelier Versace Fall-Winter 1997-1998

YVES SAINT LAURENT FIFA WORLD CUP 1998 FINAL PRE-GAME COUTURE SHOW

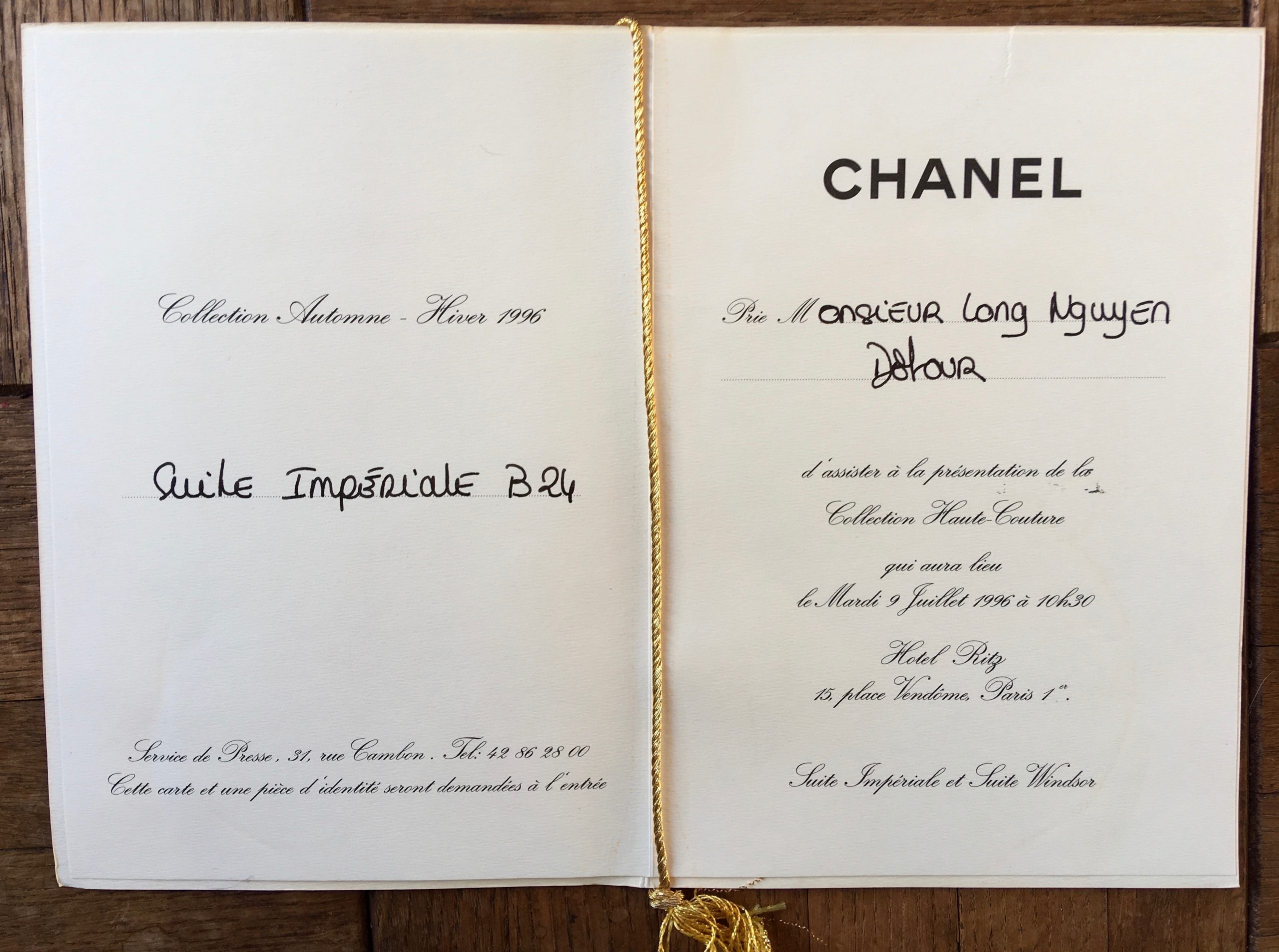

CHANEL HAUTE COUTURE FALL 1996

And, in early June 1997, Gianni Versace showed his final collection Atelier Fall-Winter 1997-1998 at the pool of the Ritz in a dazzling, spectacular combination of his career signatures of sex, baroque, and splendor. Finally, perhaps the grandest fashion show I have ever attended was the Yves Saint Laurent Haute Couture pre-game show at the Stade de France just before the FIFA World Cup Final in July 1998 between France and Brazil.

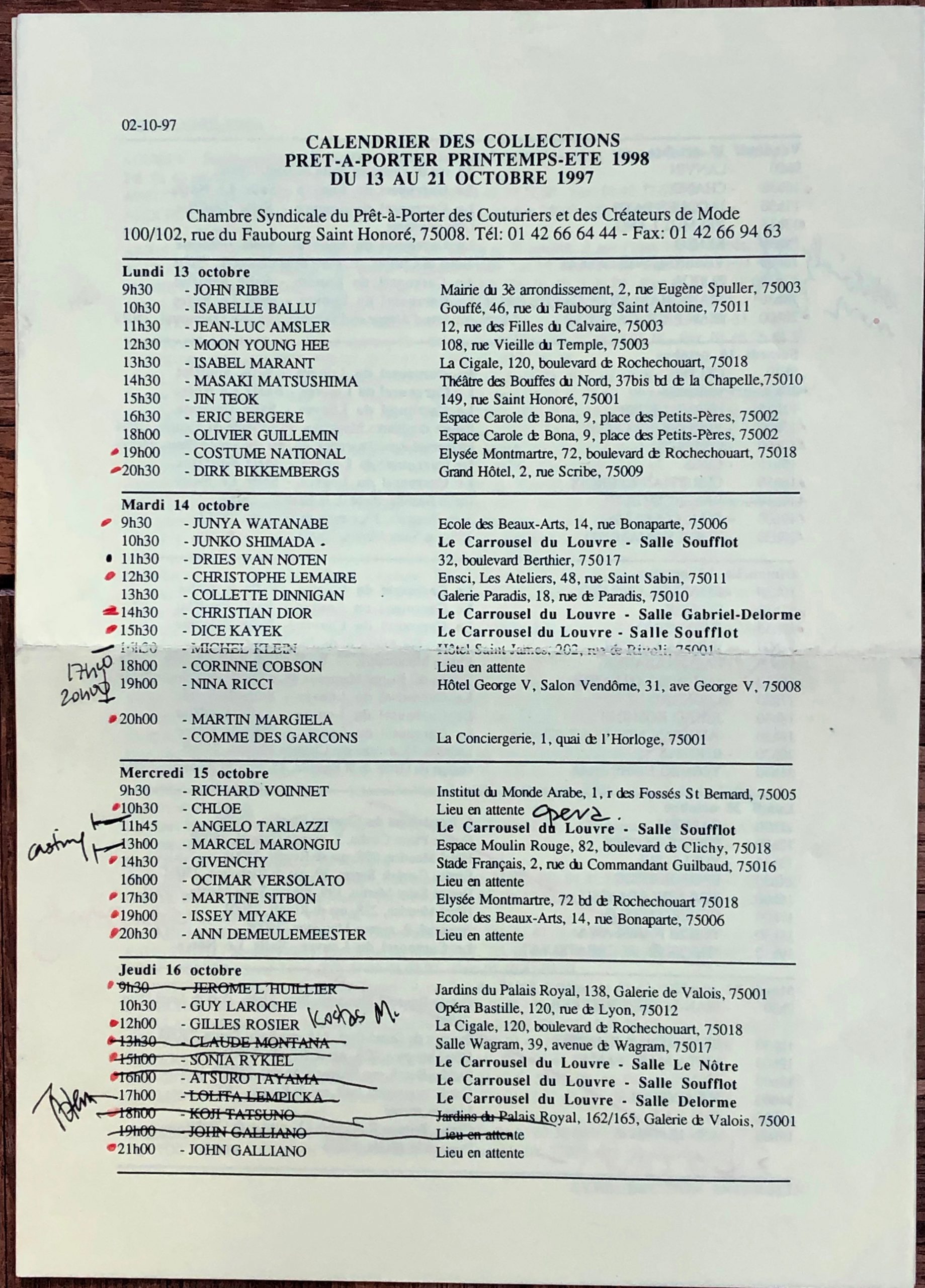

Paris Men’s Spring-Summer 1996

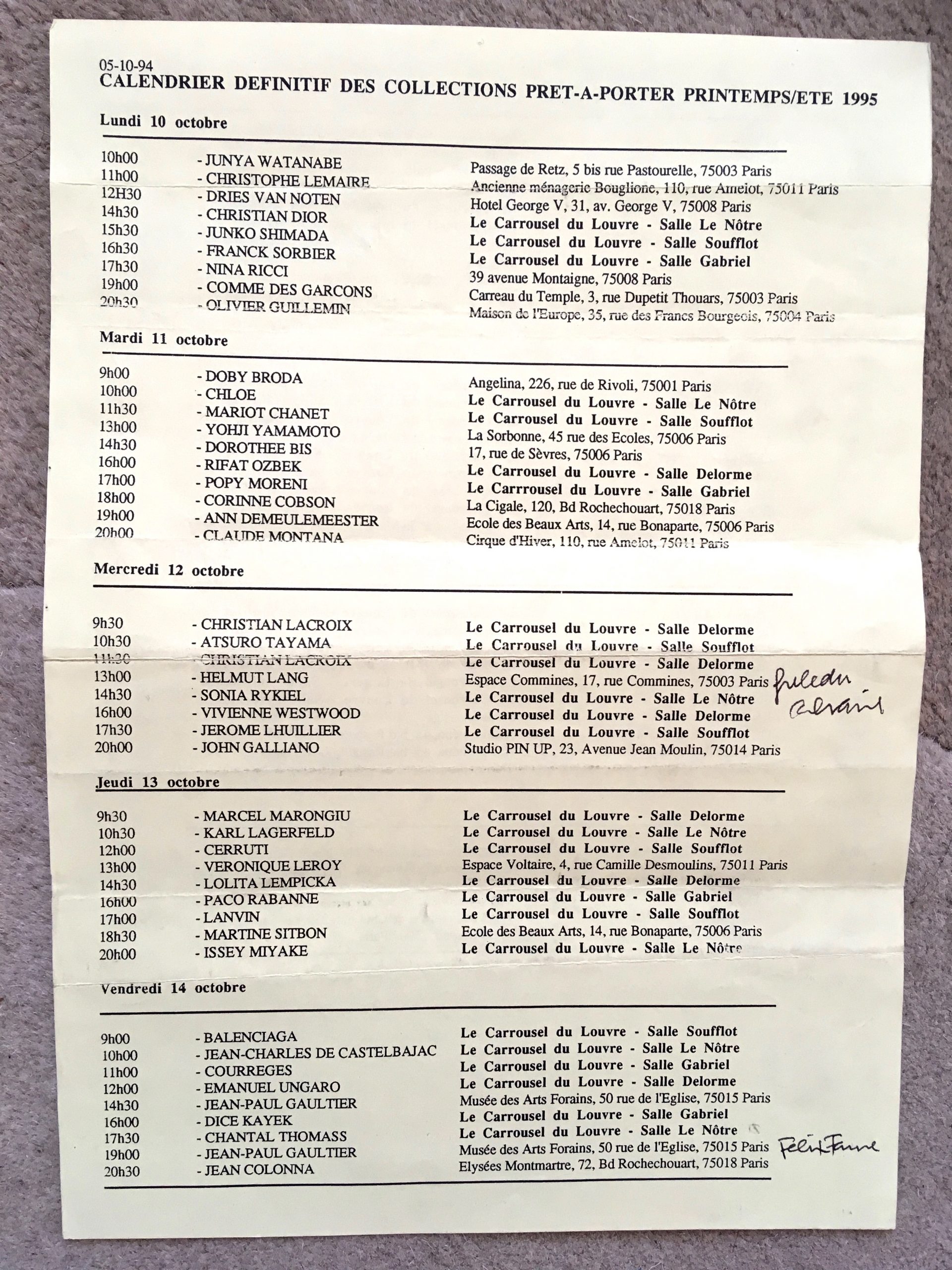

Paris Women’s Spring-Summer 1995

Paris SS1998

Yohji Yamamoto Pour Homme Spring 1997

At the time, I remembered the exact feeling each time I left these shows that were far more than just about clothes. The rite of passage into our adulthood in fashion as outside tribes – the newly emerged creative class of young actors, photographers, magazine editors, musicians, stylists, and businesspeople – now all had a voice and a platform and beautiful clothes to wear. It is hard to imagine the enormity of these designers’ contributions in the 1990s far beyond just physical garments. The 1990s was an era of primal transformation, and for those involved in the era’s creativity, it was like holding up a mirror and looking at ourselves and others.

Those momentous 1990s fashion moments are now part of the pantheon in fashion history, serving as a mirror for an exceptional decade. Now, the diaspora of designers and brands are returning to the pre-pandemic live show to regenerate the fashion circuitry for a new era. The question isn’t why this particular platform and format of live presentations remain the only possible way to show new collections but whether there is sufficient creative juice in the same veins as we had seen in the 1990s. The return to fashion’s greatness – whatever that means – hinges on the level of insight and creativity, the lodestone of fashion’s future that can incite a broader environment in society at large. The game is now on the designers to lose.

The problems facing fashion now are acute and manifold. One side will be how the industry evolves with innovative approaches to presenting fashion after this issue during the last sixteen months. On the other is the absolute critical return to creativity as the only way to propel fashion-forward, a creativity level on par with that in the 1990s. However, there are rooms to hope, despite fashion’s rapid ability to disguise appearance and reality making any clear assessment cloudier.

New York West Chelsea March 30, 2020 Lockdown

New York Black Lives Matter June 3, 2020

Live shows coming out slowly from the pandemic are a lot smaller than they were beforehand, demonstrating that borders are not completely open and that brands may not want to rush back to the extravaganza so fast. Yet returning to the overwrought and hyper-expensive production – even under the guise of more sustainable practices like donating used runway wood planks for secondary uses – seems at best pushing the replay button, not evolving the system.

Since taking creative leadership at Chanel in 2019, Virginie Viard has downgraded the era of flashy stage sets, each season seeing reductions in elaborate constructions around each new collection. The current renovation of the Grand Palais under Chanel’s sponsorship has the brand scaling down its Fall 2021 haute couture live show staged in the courtyard of the Palais Galliera without a physical runway or any other decorations and with just two small rows of socially distanced chairs for guests.

Digitization cannot replace the experience of live shows – while that is true, as only a few get actually to experience live shows. Recently at the Paris fall 2021 haute couture show, I experimented on this difference in life versus digital fashion showing. I went to the 10 AM Chanel live show at the Palais Galliera and then waited until 3 PM Paris time to view the show again as a digital premiere at the brand’s website. The time delay in the broadcast was that it was too early morning in New York and around rush hour end of the workday in Shanghai for the show to be broadcasted live stream.

HAUTE COUTURE FALL 2020 DIGITAL

CHANEL HAUTE COUTURE LIVE

CHANEL HAUTE COUTURE DIGITAL

I can say without any doubt that seeing the models wearing each of the haute couture garments as they stepped down the short staircase entrance to the Palais Galliera museum is far superior to any other way of looking at clothes. In absorbing the utter beauty and understanding of the process of these actual handmade garments. On-screen, the clothes don’t convey that sense of handicraft. You can’t get a feel for the garments, unlike how when the models walked in them.

That said, so much of fashion in the Internet era has not been about fortifying this understanding but rather about viral commentaries on the actual visual impact of the shown look. ‘Fabulous flower dress’ is a common and more than adequate description of the official ‘tiered dress and cropped trousers in white organza in light, the ethereal composition of ombré feathers combined with Pointillist graphic sequins and floral pom-poms in white marigold and peach organza.’

The vocabulary to describe clothes is changing, but the industry is still reluctant to change the way to create the visual. Perhaps there are no better ways to present clothes than in a live format – real, not Memorex (King of VHS videotapes back in the days). However, there is no reason to completely dispel how the digital format can garner a grand audience if crafted with ingenuity and creativity. Again, greatness, live or digital, depends on harnessing creativity.

Indeed the pandemic has given rise to several new terminologies unheard of beforehand – the essential workers and critical businesses.

Unlike sports, live fashion shows with no audience were a format that few brands experimented with as an alternative during this period with bans on public gatherings. In Europe, football games in the Premier League, Ligue 1, La Liga, the Bundesliga, and Serie A were the first to stage an entire delayed season without any audience presence.

The pandemic year exposed many undercurrents in society that were previously impervious to casual observers. For one, we now know the particular category of essential workers who toiled during the lockdown period to provide critical and infrastructural functions to keep things going at least at the bare minimum. We got to know health care workers, groceries clerks, Amazons and Grub Hub deliverers, as well as bus and subway drivers.

Similarly, in fashion, the manufacturing and the supply chains came into focus as production came to a halt, leaving the cracks in these systems in a transparent way for many to see.

Like in society at large, the pandemic exposed all to the transparent income inequality across the U.S. For the first time, everyone learned of a new term – essential workers – the bus and subway drivers, the supermarket clerks, the health care first responders – just as the break in the supply chain of goods first noticeable in toilet papers, then, gradually through the entire production pyramid from Bangladesh to Guangdong to Biella, Prato and Como.

Most on everyone’s mind is simply the idea of the supposed ‘roaring 20s’ referring to the extravagant post-WWI years where the opulent dressing was the norm as a predicate relief and outright revenge from the sweatpants era. But, rarely is there an honest discussion about innovative fashion design.

It is by now an adage, or perhaps putting it in a better way, a saying repeated so often that the meaning contained within has evaporated into thin air. Yet, this is something enduring that the pandemic year can serve as a profound moment of reflection, an inflection instant providing considerable opportunities to reconsider, reorganize, and revolutionize every aspect of the fashion industry seemingly in the cusp of significant anthropomorphic alterations.

In the third wave lockdown, it was commonplace to think of the kind of rosy predictions that the pandemic has to be a precursor to a better future for fashion. It is predominantly coming from the younger generation of fashion designers across the globe, leading the charge from here to there.

The return of physical live shows with the audience is undoubtedly a cause for celebration, but this should not cloud the fact that the few recent years before the lockdown were also the years of fashion show glut and boredom.

Raf Simons Fall 2021

DIOR SPRING 2021

VALENTINO HAUTE COUTURE SPRING 2021

PRADA Fall 2021

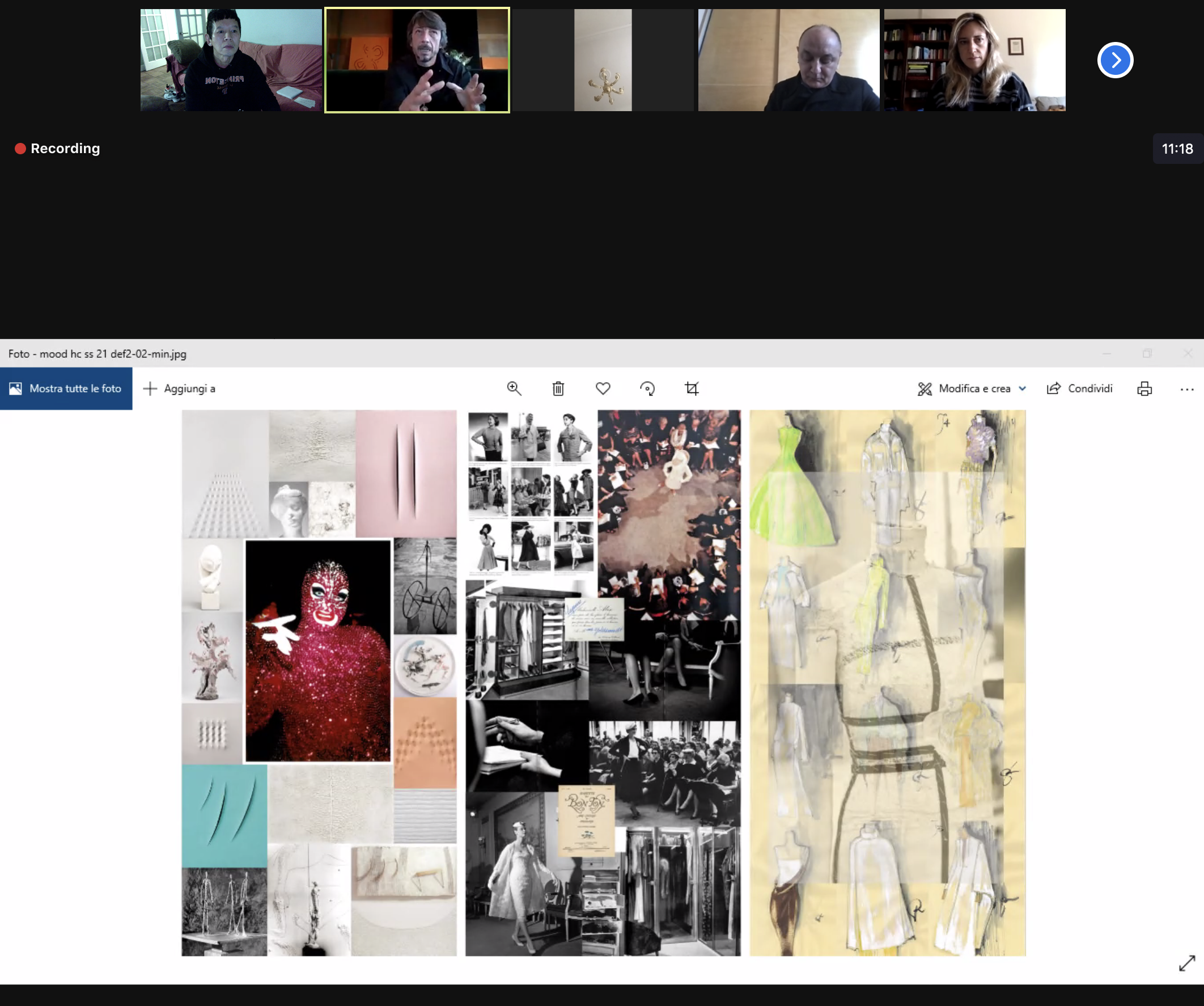

GUCCI ARIA Fall 2021

Can the fashion industry come out of the pandemic year crisis pretending to be the same industry it was in March 2020? The old fashion order prevalent to the end of Fall 2020 shows in Paris last March seems ready to be toss during the on and off waves of lockdowns that appeared to have an upside-down impact on how the fashion world will move forward anew.

IMG has given out contracts to about eleven American designers – Altuzarra, Sergio Hudson, Brandon Maxwell, Proenza Schouler, Rodarte, Monse, Telfar, Markarian, Jason Wu, LaQuan Smith, Prabal Gurung – to produce a live fashion show at their Spring Street hub this September.

In the aftermath of the year of total disruptions, fashion is entering a different era with a new landscape for the luxury business, exposing how the company is done from design to procurement to manufacturing and consumption. Taste is changing so too is the perception of the trust in and the values of brands.

The definitive schedule for the newly dubbed American Collections shows it is at best weak and at worst containing too many shows like it was in the few seasons in the B.C. era. Those rushing to return to live shows at the first opportune moment do not seem to have taken anything learned during the pandemic or least trying to figure out in creative ways divergent paths beyond scheduling the show. Of course, a fashion show is critical, but the question remains whether it is the suitable choice format for every brand, big or small.

American fashion now depends less on the big commercial brands than on the crop of young designers coming of age in the decade of the Internet. The most interesting and the most creative shows this coming season, starting next week, will come from the designers who bring the utmost personal views – their own – into the very fabric of their work. The production and consumption of fashion and how to get a community into the creative practice are values these designers share with their fans.

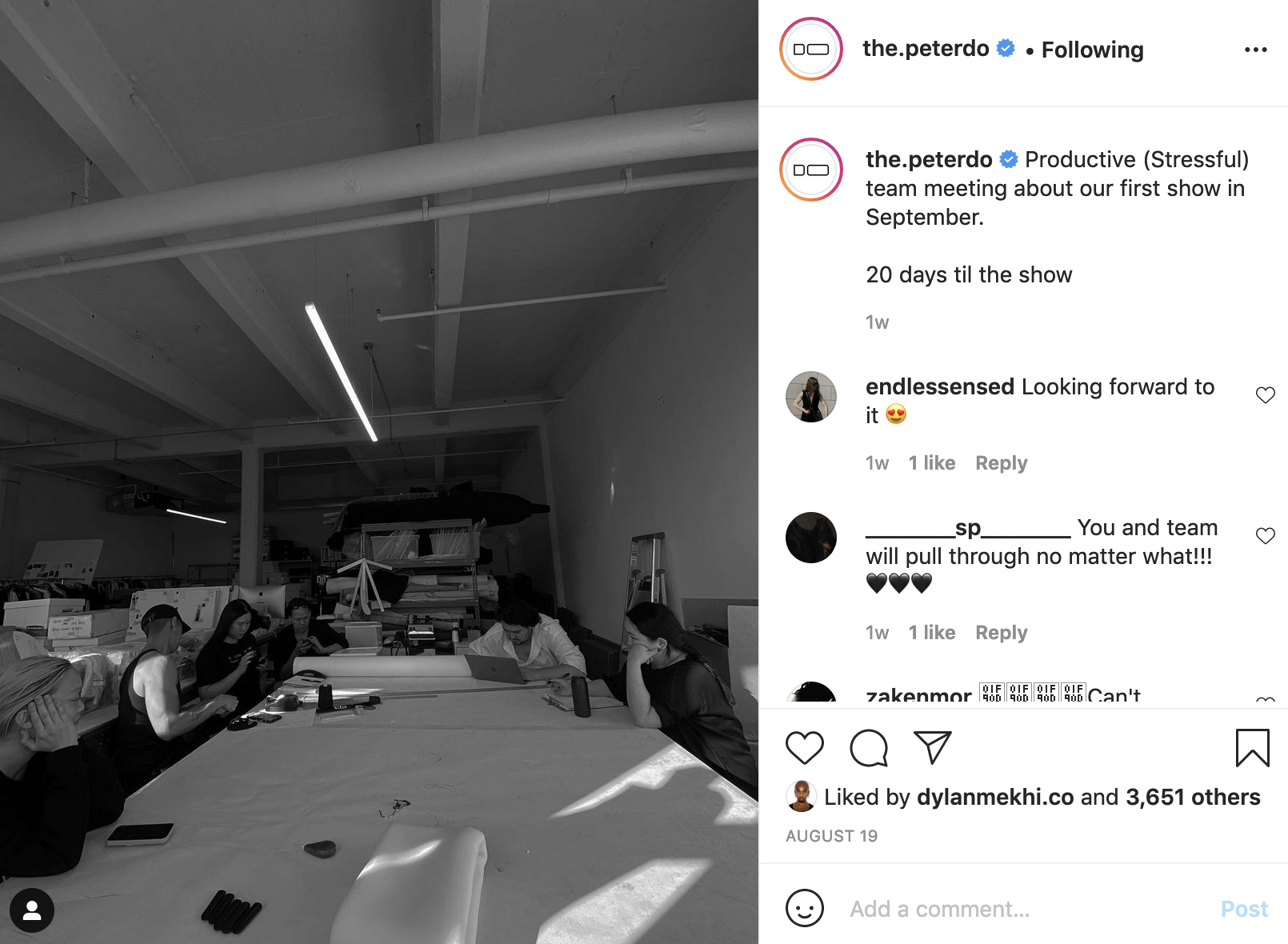

For Spring 2022, there are outsized expectations for Peter Do’s debut show to deliver that creative quotient for New York in the same way that Larazo Hernandez and Jack McCollough at Proenza Schouler did in 2002.

Hillary Taymour at Collina Strada, Telfar Clemens at Telfar, Mike Eckhaus and Zoe Latta at Eckhaus Latta, Patric Dicaprio, and Bryn Taubensee at Vaquera, Sergio Hudson, Connor McKnight, Kenneth Nicholson, Willy Chavarria, Taofeek Abijako, Sintra Martins – these are the voices in New York of this generation making fashion and conveying specific aesthetics not solely producing more cute commercial products. The different nuances that these designers brought into their marginal spaces make their work intense without the need or the fixation on the diversity struggles, which by now have become less and less inundated with true meaning.

Sergio Hudson

Collina Strada

Telfar

Willy Chavarria

Eckhaus Latta

There is hope too that Thom Browne will deliver a spectacle of fashion and fantasy as the designer return to New York after decamping to Paris first with men for Spring 2011, then women for Fall 2018, and finally in co-ed format from Fall 2020.

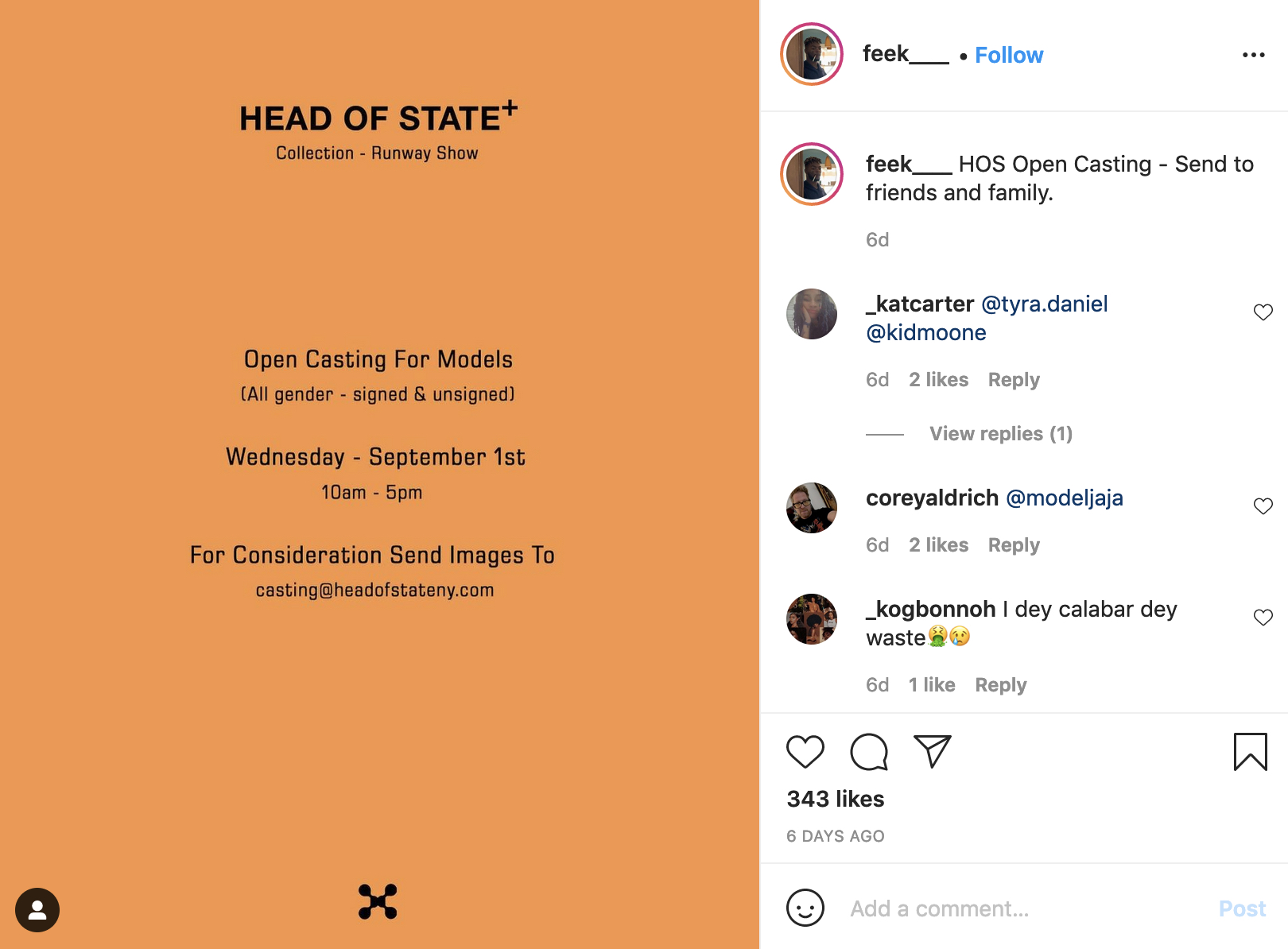

Head of State Taofeek Abijako

Vaquera

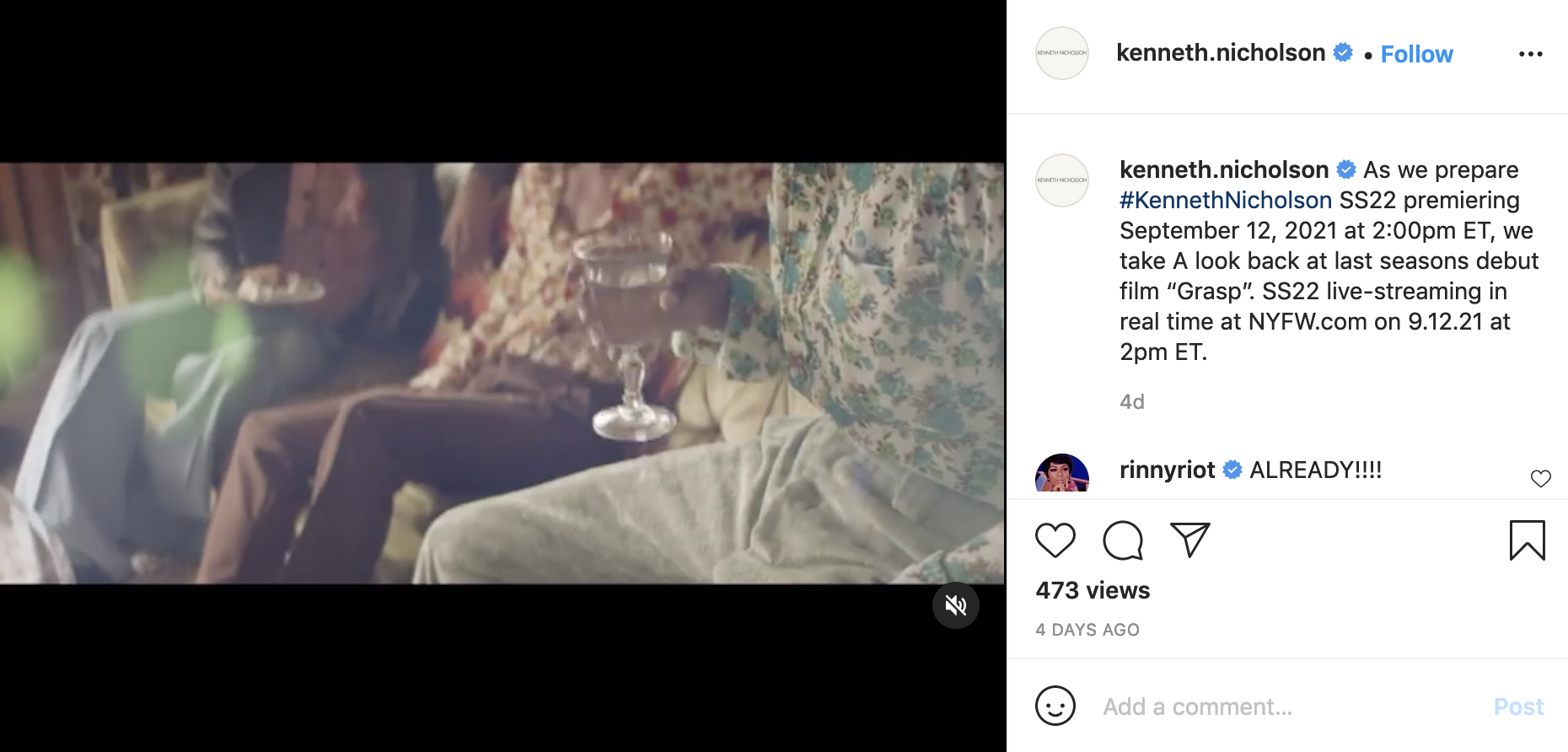

Kenneth Nicholson

Connor McKnight

Thom Browne

Proenza Schouler

Tom Ford

In Paris, this is the new generation setting the standards aiming for radical greatness – Florentin Glémarec and Kévin Nompeix at Egonlab, Ludovic de Saint Sernin at LDSS, Archie Alled-Martinez, Marine Serre, Boramy Viguier, Glenn Martens, Nicolas di Felice at Courrèges, and Arnaud Valliant and Sébastien Meyer at Coperni. They join designer Rick Owens continues experimenting and transforming shapes of his own to carve a path forward.

Priya Ahluwalia, Bethany Williams, Wales Bonner, Antonio Vattev, Bianca Saunders, Richard Quinn, Nicolas Daley, Emma Chopova and Laura Lowena, Matty Bovan, Charles Jeffrey, Eden Loweth, Craig Green, Gareth Wrighton, Harris Reed, Kaushik Velendra, and Paolo Carzana are taking London to the cusp of novelty and hybrid culture.

In Milano, the Miuccia Prada and Raf Simons duo creators define a new horizon with their new template. New voices in Milano too are emerging to change the conversations – Francesco Risso at Marni, Loris Messina and Simone Rizzo at Sunnei, and Daniel Del Core – and bringing their fashion to new audiences.

Suppose the start of the so-called post-pandemic fashion is an absolute rebirth turn around, bringing fashion back as an authentic influencer of culture like it was in the 1990s. In that case, it will have to fall on the shoulders of these young independent spirits and rule-breaking designers, not so much from the amalgam of corporate fashion. And these kids are now smart enough to get the point of a viable off-the-runway business to create more fashion the following season. There is no guarantee, just a sure bet that these young designers will now be responsible for making this next round of shows into a defining season.

There is hope, not guarantee, on the horizon.

Consider the epic and historical fall 2021 haute couture season in Paris, Venice, and Hudson Valley in New York. Demna Gvasalia set forth a new stencil for his reintroduction of couture at Balenciaga, an act and a collection bringing forth the house’s architectural heritage designed again for a new age. Paolo Piccioli conveyed a breathtaking collection with voluptuous clothes in stark bright colors, totally updating the vestiges of the Valentino heritage and ethos.

Balenciaga Couture

Valentino Haute Couture

Pyer Moss

CHANEL HAUTE COUTURE

Dior Haute Couture

Armani Prive

While the intellect at Balenciaga and the emotion at Valentino bookended the fall couture season, Maria Grazia Chiuri at Dior and Virginie Viard at Chanel kept their collection superbly tactile for the clients. Giorgio Armani showed a concise collection, adding a bit of shine in the pared-down garments. Chitose Abe crafted new Gaultier Paris couture her way. On the other side of the Atlantic, Kerby Jean-Raymond joined the couture rank this time via a postponed live showing in the Hudson Valley, celebrating black inventors and changing the generational dialogue about fashion’s ownership and authorship.

And the smaller brands designers take on haute couture by challenging traditions and moving beyond the past – like Iris van Herpen, Ronald van der Kemp, Julie de Libran, Charles de Vilmorin -espousing their collections with values entrenched in youth culture. They are bringing their ideas to life via collections and couture forms. There is also the greater sense of ownership of heritage and history.

Iris van Herpen Haute Couture

Julie de Libran

Gaultier Paris

Maison Margiela Artisanal

Giambattista Valli Haute Couture

Charles de Vilmorin

Ronald van der Kemp

Alexandre Vauthier Couture

Here is another thing to think about the mood of the pop-cultural landscape in the 1990s and now.

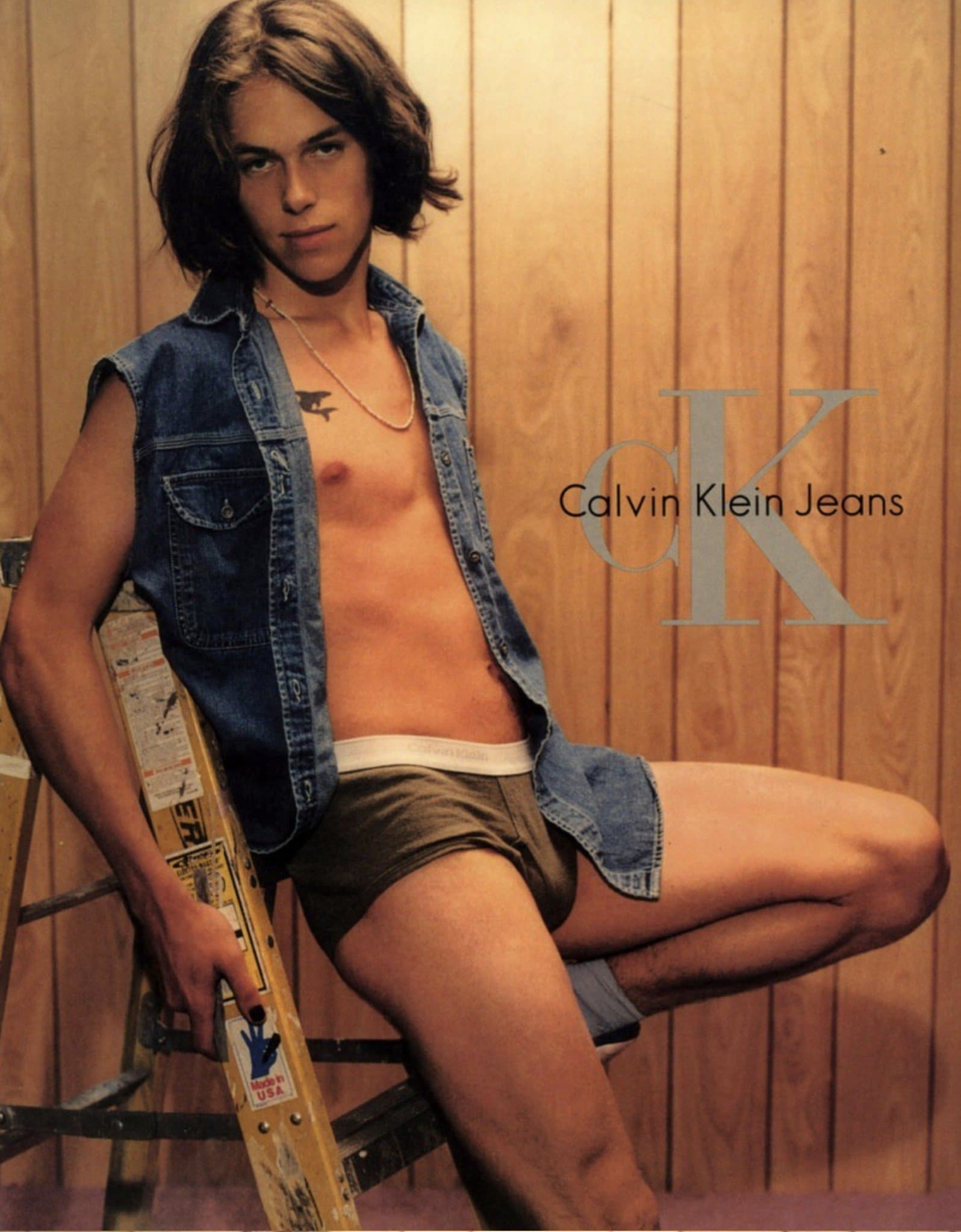

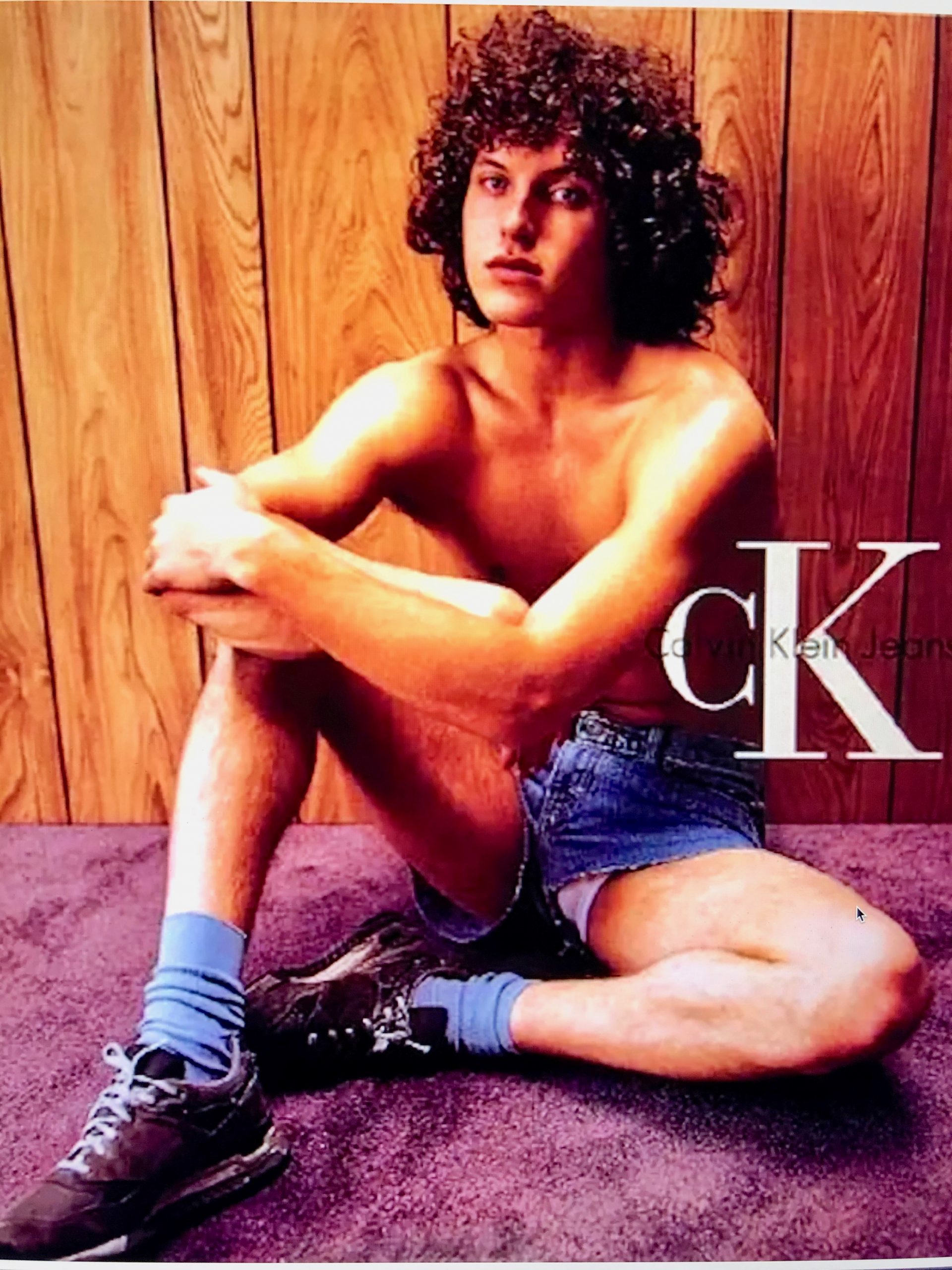

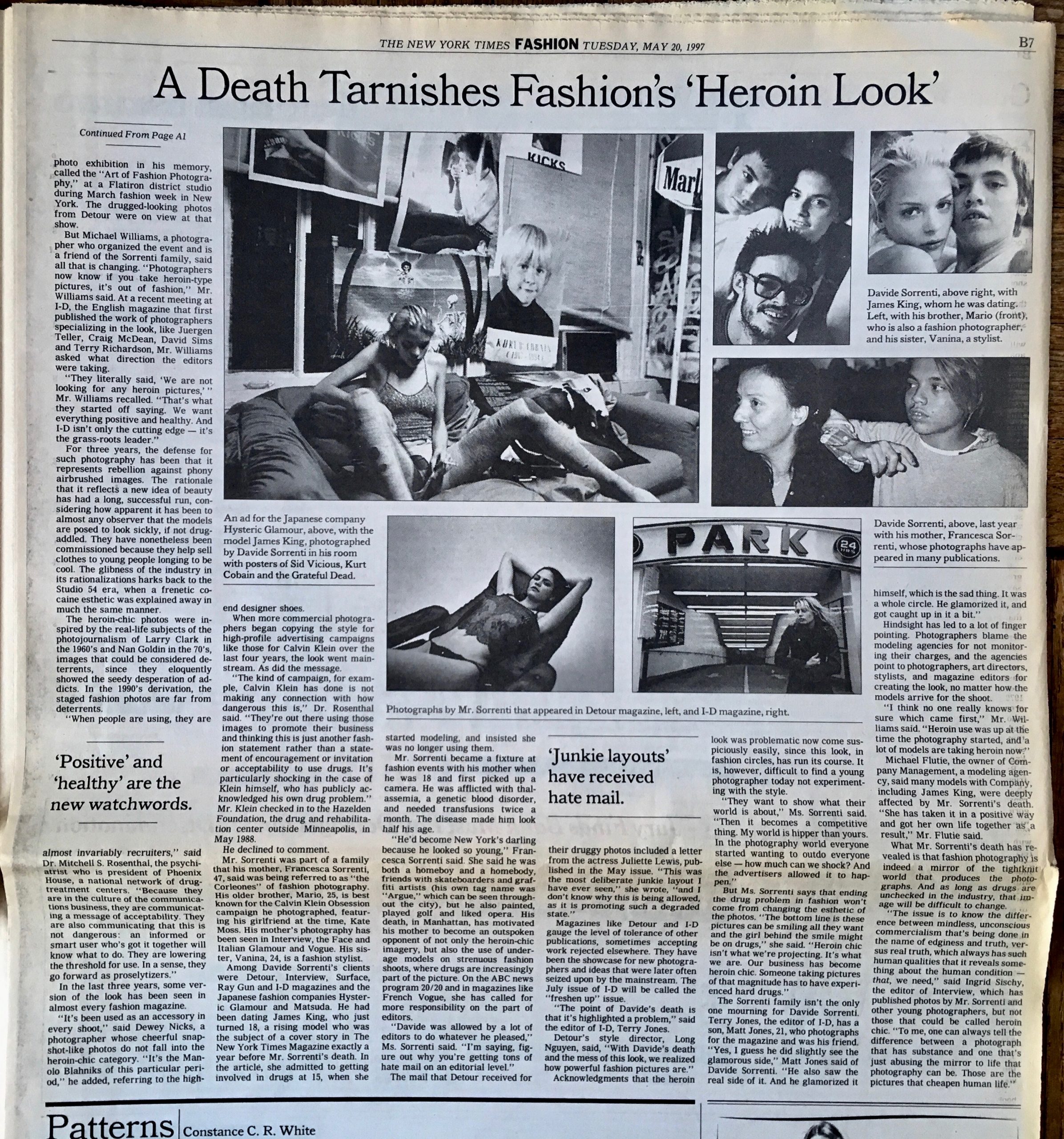

In the mid-summer of 1995, Calvin Klein began the ad campaign for the fall CK Calvin Klein Jeans lines on buses, billboards, magazines, and a limited run of T.V. commercials featuring a series of young guys and girls photographed against a cheap wooden plank backdrop and purple carpets. The very young-looking models wore sleeveless denim shirts and old underwear briefs, denim jeans, tank tops, or micro denim skirts barely covering the outline of a white panty and a cropped ribbed tank, or cut off hot denim shorts with parts of the boxers peeking out.

Even before the images and videos of the campaign took hold in pop culture at large, the brand, under severe and misguided criticism even from the Justice Department for promoting kiddie porn, canceled the massive installations going globally that fall. In the studio setting of the wood-paneled carpeted basement with few staging tricks saved for a cheap ladder, Klein and the photographer Steven Meisel were able to portray the spirit of youth owning their adulthood and their bodies in the act of affirming correctly what the designer said at the time as ‘the spirit, independence and inner worth of today’s young people.’

That jeans ad campaign was indeed reflective of the emerging spirit of youth and independence.

CK CALVIN KLEIN JEANS FALL 1995

CK CALVIN KLEIN JEANS FALL 1995

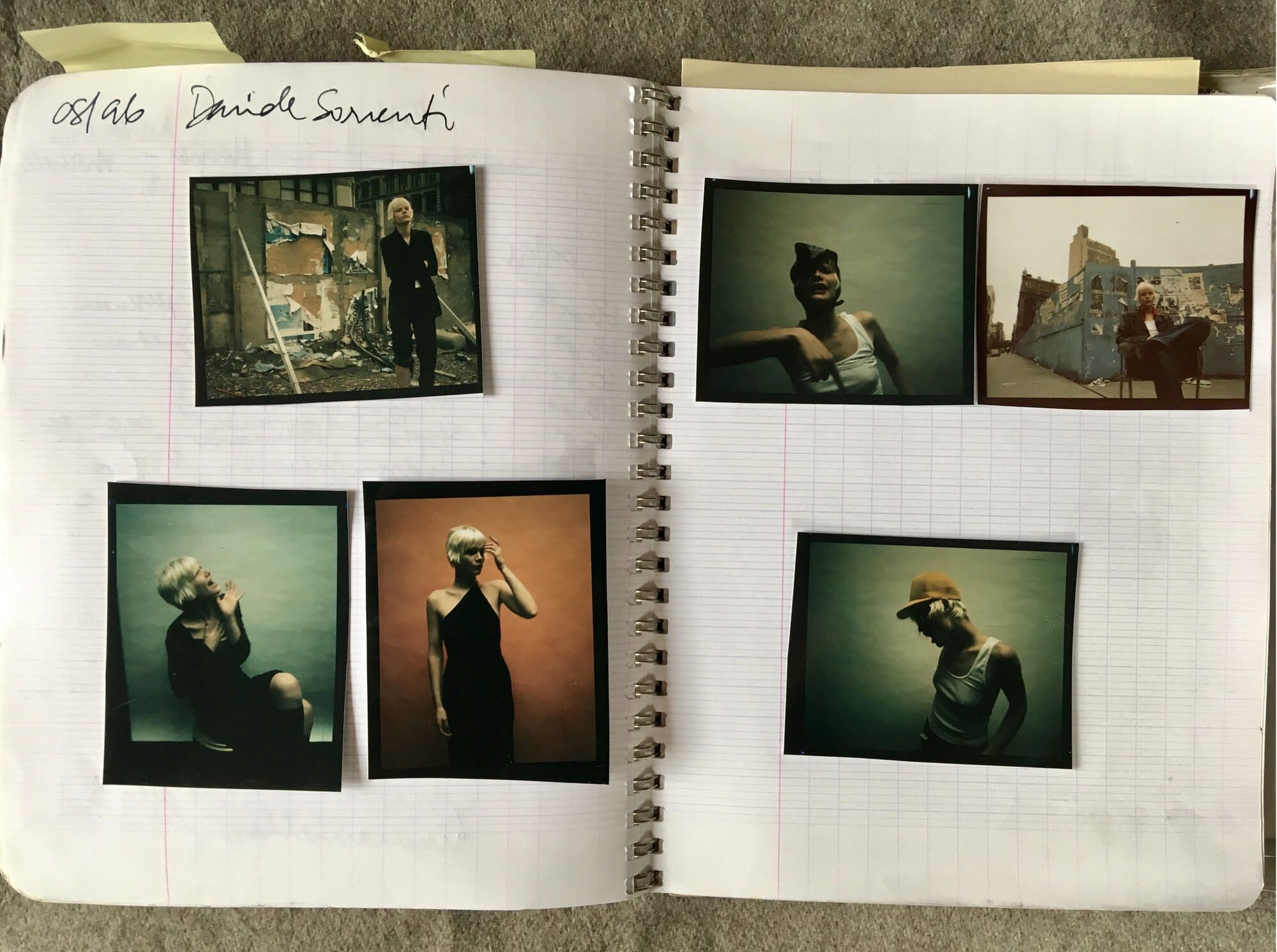

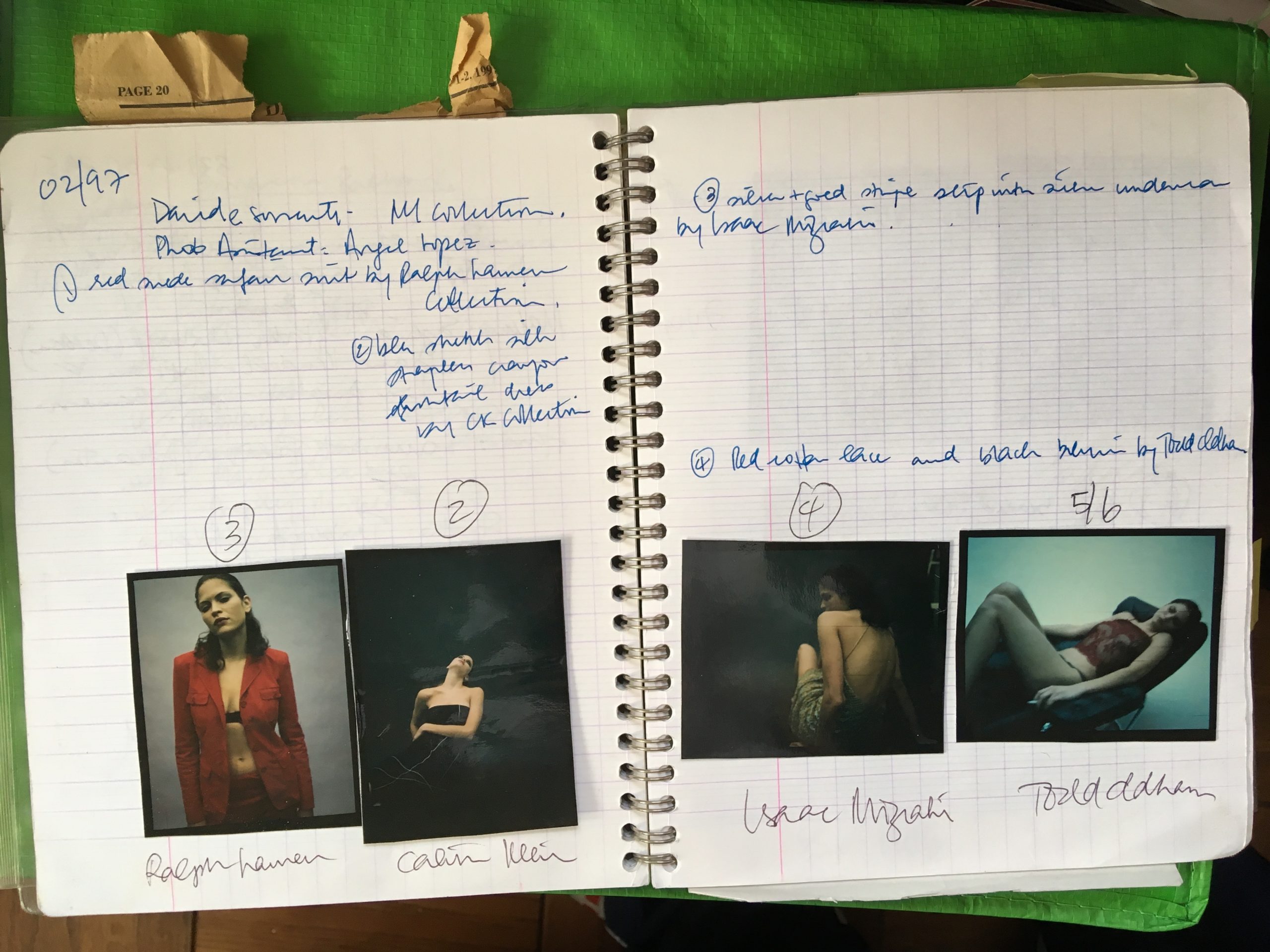

At the time, I defended the C.K. Jeans campaign, as the outrages were at best manufactured and at worst acts of negating a generation their say. Among other faux pop-cultural crises of the 1990s era was the ‘heroin chic’ crisis in mid-1997 when the front page of the New York Times falsely labeled a precocious young photographer’s death – Davide Sorrenti – as a perpetrator of a style of photography where models seemed high on drugs. Of course, there was no such thing but make beliefs were what they were. I collaborated with Sorrenti in his last and only working year of his life. Instead of celebrating youth creativity, the interpretation was as some drug-infused way of working. Sorrenti’s pictures had nothing to do with drugs.

DAVIDE SORRENTI February 1997

New York Times, May 20, 1997

NEW YORK TIMES May 20, 1997

Fast forward to today, instead of youth at the forefront, it is the Carters flouting their super wealth in a super-boring ad for the LVMH owned Tiffany jewelry. In the miscalculate principle image of the campaign out now, Beyoncé stood stoically like a statue in a black Balmain sheath, hands on her hips, and that 129 carats ‘blood’ diamond from the colonial era that was only previously worn publicly by three other women. At the same time, her husband gazes at her from the comfort of a leather couch.

CK Calvin Klein Jeans Fall 1995

TIFFANY FALL 2021

It wasn’t so much about the giant diamond mined in colonial South Africa that should disturb. It’s just that the image, frozen from another space and time, portrayed the exact income inequality in America that has exacerbated during the pandemic and nothing of the sort of an apotheosis moment for today, especially for young people. Sure one can say that making it big is a value, but it just isn’t that juicy for young kids. But that’s the difference today between corporate branding control and independent fashion labels talking directly to Gen Z.

The pandemic isn’t the apocalypse, but the momentary pause allows long-dormant questions to emerge to the fore like a giant hot air balloon rising to the surface of a deep lake.

The fashion industry can find some good things coming out of the pandemic should not be a surprise as there are plenty of areas prime for improvements. But to say that fashion in this new era will be more sustainable, less waste and minor environmental damage, less racist, more inclusive, less greedy, and indeed a kinder industry is at best wishful Utopian thinking.

Fashion should be different starting from Spring 2022. But will the industry be transformed if the prime directives emerging from the perennial industry leaders now are nothing more than a full-speed resurrection of the status quo from Fall 2020 – a speedy reincarnation to close that lost year time gap quickly. Then there were too many shows that bear no reason.

Unbridled creativity – the heritage of the 1990s, especially from the mid to the turn of the twenty-first century – ushered an era of prosperity and propelled brands into giant corporate enterprises. Now the youthquake must produce the same augur to drive fashion past the pandemic era busts, and that’s isn’t just about convivially making a bunch of dressed-up garments for people to go to the disco. Let’s see if the optimism of the haute couture fall shows is infectious enough.