By Mark Wittmer

The Iconic Photographer Talks Shooting New York City During Lockdown and His New Book

Mark Seliger is one of today’s most prolific and influential photographers. Renowned for his iconic portraits, his work shapes the way we think about image, celebrity, music, and fashion. As Rolling Stone’s chief photographer from 1992-2002, he shot over 175 of the magazine’s covers. He is also instrumental in shaping the photographic landscape of contemporary fashion, producing editorial work for publications like Vanity Fair and Italian Vogue, as well as defining the visual language of marketing communications through brand collaborations.

While Seliger is most renowned for his portraiture, during the pandemic and ensuing lockdown, the photographer turned his camera toward a different subject: his home of New York City, the streets of which were, for the first time in living memory, empty. The beautiful, haunting, and hopeful photographic results of this period of documentation have been gathered in a new book aptly titled The City That Finally Sleeps. Embodying the images’ quality of hope and resilience, 100% of the proceeds from sales of the book will go to New York Cares, a nonprofit volunteer organization based in the city.

The Impression’s Mark Wittmer caught up with Seliger over Zoom to talk about the process behind the unique project and to celebrate the launch of the book.

Mark Wittmer: To start off, I was wondering if you could talk a little bit about what was in your mind at the beginning of the project, which lined up with the beginning of lockdown -what were you thinking when you were getting out and shooting in those early days?

Mark Seliger: I didn’t even think of going out and doing it because it just seemed so obvious. In your mind you’re thinking, “Oh it’s just buildings, empty streets, empty stores, and restaurants not open.” It just seemed so dull. However, one night I was driving back home through the West Village, and it was one of those very moist dusks, slightly gray; the streets were completely slathered with rain and dew. And it was just beautiful because nobody was on the street, the city was in full bloom in spring, the cherry blossoms were just overflowing the street at the peak of their blooming. It almost looked kind of Hopper- or Magritte-ish; it had this perfect melancholy to it. I took one picture of an empty street, a couple cars parked, and I didn’t really think anything of it and I posted it the next day. And the reaction was amazing. People had left town; there was a lot of reaction from expats who just wanted to connect with the city. So I thought for my own sake and to keep my own momentum going – I didn’t want to fall into some sort of dark hibernation – I just went out and tried a couple of different photographs, and they started to become kind of awesome. The emptiness and the starkness of it was kind of this beautiful melancholy, and I just kept on going.

We went through mid-March all the way to when George Floyd was killed. After that, the particular phase of what we were going through with the pandemic in the city felt like it had shifted. People were reacting, the rallies started, people were marching down the street. It was this perfect storm with no tourism, New Yorkers who had the advantage had run away to their summer homes or gone to live with their parents – then all of a sudden the streets were filled with people activating. The timing just allowed people to be completely present. Everybody was listening, everybody was hearing, everybody was seeing. When the killing happened, that was so present for people. There was a sensitivity and vulnerability that led people back to this almost antithesis of what we were experiencing during lockdown.

Mark Wittmer: Did you realize with those events that the photos you had been taking were capturing a very historical moment in time?

Mark Seliger: I never really thought of them like that. I kind of just paused. It was such a sudden shift for me that I found my way through it by documenting New York, but not people. Whether it was the idea that people were taking an even deeper pause, or activating in a different way, it didn’t seem like the right story for me to tell, but rather one I had to feel. I didn’t think I should be in front of people with cameras when they were going through that kind of anger and sadness. I felt like we needed to have a moment to be able to process it ourselves rather than me being a journalist.

Mark Wittmer: There is a strong feeling in the photos of that space, that quietness and reflection.

Mark Seliger: I welcome the stillness in my life, and so for me it was very cathartic, as it was for a lot of people. It gave me the opportunity to take a couple steps back and just appreciate a lot of the beauty that I had first encountered when I came to New York, whether it was one of those quiet late summer nights walking back from a party or a bar or a concert, and taking the long way home, and noticing something – that moment when you first come to the city and go, “Wow, this is pretty magical just being here.” And then you get swept up in life, which detours you from observation sometimes. If you look at something in broad daylight and then revisit it when it’s lit by a streetlight, you’ll probably notice something more intense because it’s that reductive quality that brings you back into observation.

Mark Wittmer: I noticed that a lot of the photos I saw seemed like they were captured at dawn or dusk, in those transitional and elusive times of day.

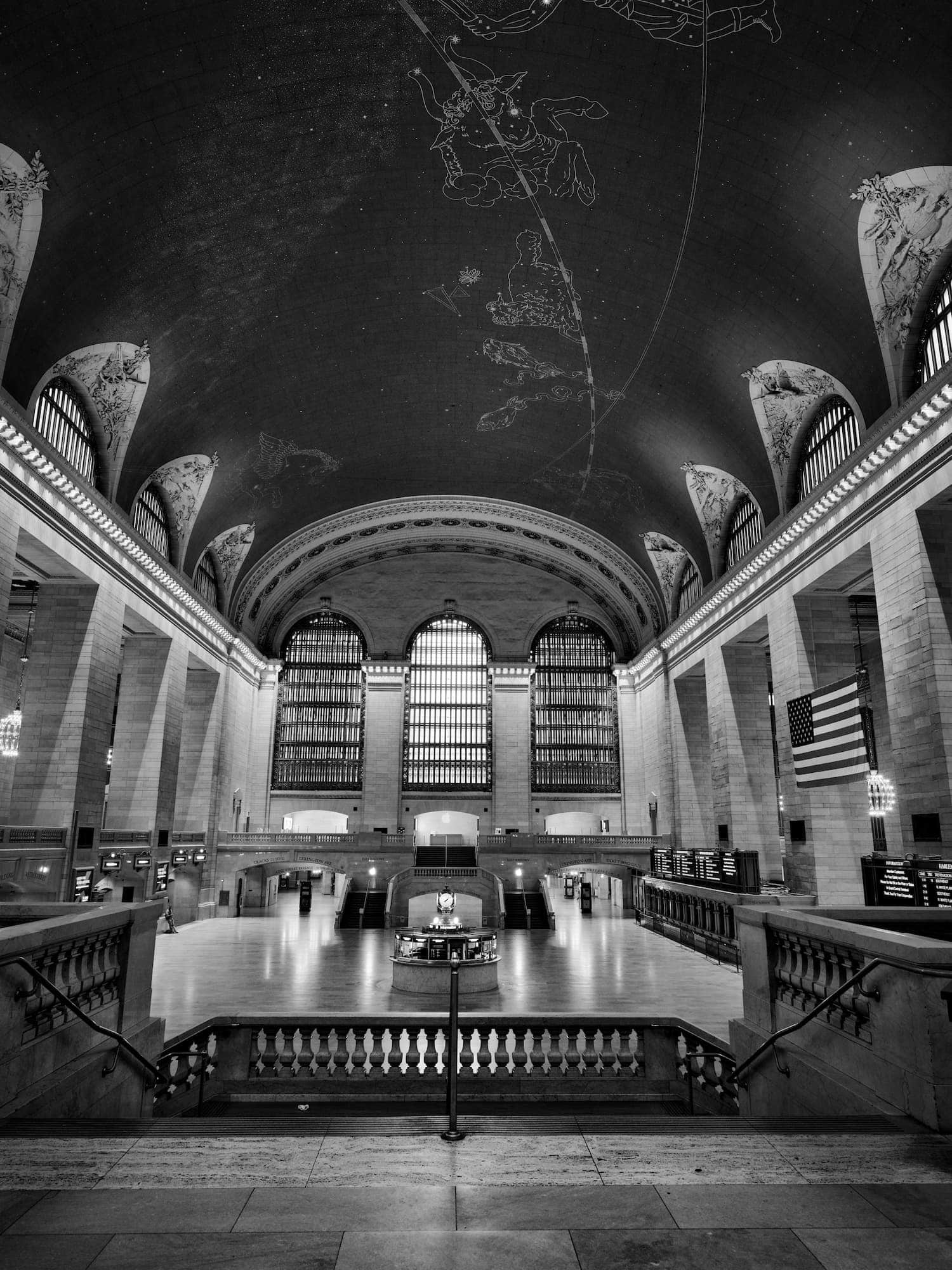

Mark Seliger: What initially led me to approach dawn and dusk was not only for the quality of light but because I was in the studio working on a few other projects through the day. Dawn seemed like the most logical time to go out for me. I’m an early riser anyway so it was nice to go out before going into the studio and just seeing what’s going on. And then it worked the same way with shooting at dusk; the days were growing longer and I could go and take it in at the end of the day. My brain is more receptive in the first thing in the morning or when I get my second wind at the end of the day. And I feel a poetry about dusk and dawn. Though there are probably a dozen pictures that were shot right in the middle of the day. I went into Grand Central at like one o’clock in the afternoon one day and there was nobody there; it was just a ghost town – or a ghost station.

Mark Wittmer: That has to be pretty intense after seeing it normally full of people.

Mark Seliger: Yes intense, but you’re kind of also pinching yourself wondering if this is really happening. I felt like I was about to be pushed into a bunch of extras on a Spielberg movie. There was maybe one guy walking around trying to figure out if he had missed his train.

Mark Wittmer: It sounds very surreal.

Mark Seliger: That’s a great way to say it. It was surreal; it was poetic. It was kind of like the best slow song you ever heard.

Mark Wittmer: It sounds like shooting the city was pretty different from your typical portrait shoot.

Mark Seliger: I worked on a book called Listen, which was built around process, platinum plating process, but it was kind of general photography themes which are still life, landscapes, and nudes. So I had already started to lean into doing cityscapes, so I was pretty familiar with how to maneuver through the city. A couple of those images were Central Park at first snow, when you have to get up really really early to beat the dogs at Central Park on a snow day. So sometimes I would go back four or five times to get a picture of what I wanted because it was so fragile. The occurrence of snow is becoming less and less in the city, and I really wanted to find that in the period that we live in. And that’s what photography is about, it’s preserving something that typically doesn’t exist after an amount of time. And the key to being a good documentary photographer is going out there and seizing the moment so that even if it’s not relevant now, it will be relevant at some point – as long as you’re relevant.

Mark Wittmer: When did this project take shape as a book?

Mark Seliger: The book was really not discussed until long after the project was completed. Then I thought that the potential of doing a book and putting it out there and having the proceeds go to a New York City charity like New York Cares could be a really good vehicle to raise some money for them. It’s always easy to write a check but it’s always nicer for people to have something to hold onto, a memento that reminds them of a certain period of time. So I thought what could be better than a documentation of this time, but not in a negative way – more in a reflective way.

So we teamed up with New York Cares, and I worked with a very talented printing house called Brilliant, and they were amazing. They spared nothing to do a really beautiful job on it. We made a very small limited run; we decided for it not to be a bookstore option because we wanted it to have an immediacy so that people could have it at the time it was still relevant, and also to be able to donate a nice chunk of change to New York Cares, which is a volunteer-based organization that focuses on people in need in the city, from hunger issues to housing to education. It seemed like all the ducks were in a row once we decided to create a relationship with this amazing organization.

Mark Wittmer: The images make a lot of sense for that kind of project. As haunting and surreal as some of them are, they also feel very hopeful: the cherry blossoms coming out.

Mark Seliger: That was the dichotomy, that was the moment where nature continues. We have no control over that. It could be something as crazy as a pandemic virus, or something as overwhelming and beautiful as cherry blossoms lining the street. We don’t control nature, we can only live in these boundaries and figure out. And there was very much the story that I was trying to tell. There’s a rhythm to both sides of things; we’re always just trying to navigate through them.

The City That Finally Sleeps is available exclusively through the website of Mark Seliger Studio. 100% of the proceeds go directly to New York Cares.