Neil Sharman – The Future of Physical Retail

By Mark Hooper

Neil Sharman, Burberry’s Director of Architecture, on the enduring importance of brick-and-mortar stores, how to deliver theater and spectacle in the age of digital, and why it’s often best to look back to go forwards…

In his 12 years at Burberry, Neil Sharman has overseen an inspiring range of store designs, installations and pop-up projects that have included the legendary Makers House fashion-show-as-exhibition on London’s Regent Street, as well as creating everything from ski lodges to giant mirrored islands in the name of retail. Who better then to survey the changing landscape for luxury brands: and to explain how digital and physical space can inform and feed off each other? Fittingly, we ditched the Zoom calls to meet in a real, live, bustling café in the middle London’s burgeoning King’s Cross development to discuss the best way for fashion companies to entice their customers back through the door. It’s all about delivering unforgettable experiences, Sharman insists. And he should know…

Mark Hooper: The role of physical, brick-and-mortar retail has obviously shifted in recent years – where now perhaps it’s more focused on an experiential space, where you engage with the brand, but the transactional part might now take place online…

Neil Sharman: For me, it goes back maybe 10 years before lockdown, let alone all the things we’ve seen immediately pre- and post-Covid. Some of the stuff I was working on at an earlier time in my career (I was founding director at a studio called Campaign Design) feeds into what we’re talking about now. We worked with Future Laboratory on an idea called Sweet Shop, where customers before they got to the store, would feed in some data. And that data would reflect the experience they had in this exhibition space. It was quite a simple but entertaining way of creating ‘retail theater’. We had to call it something! We had actors involved, people would get to experience part of the space before they got there, so they got to understand a bit about the journey, but not all of it – and that led into this moment of ‘surprise and delight’, which is what we all want out of a space. And that I think links to what we at Burberry designed pre and during lockdown, but delivered mainly after.

Mark Hooper: And lockdown has lasted much longer in China of course…

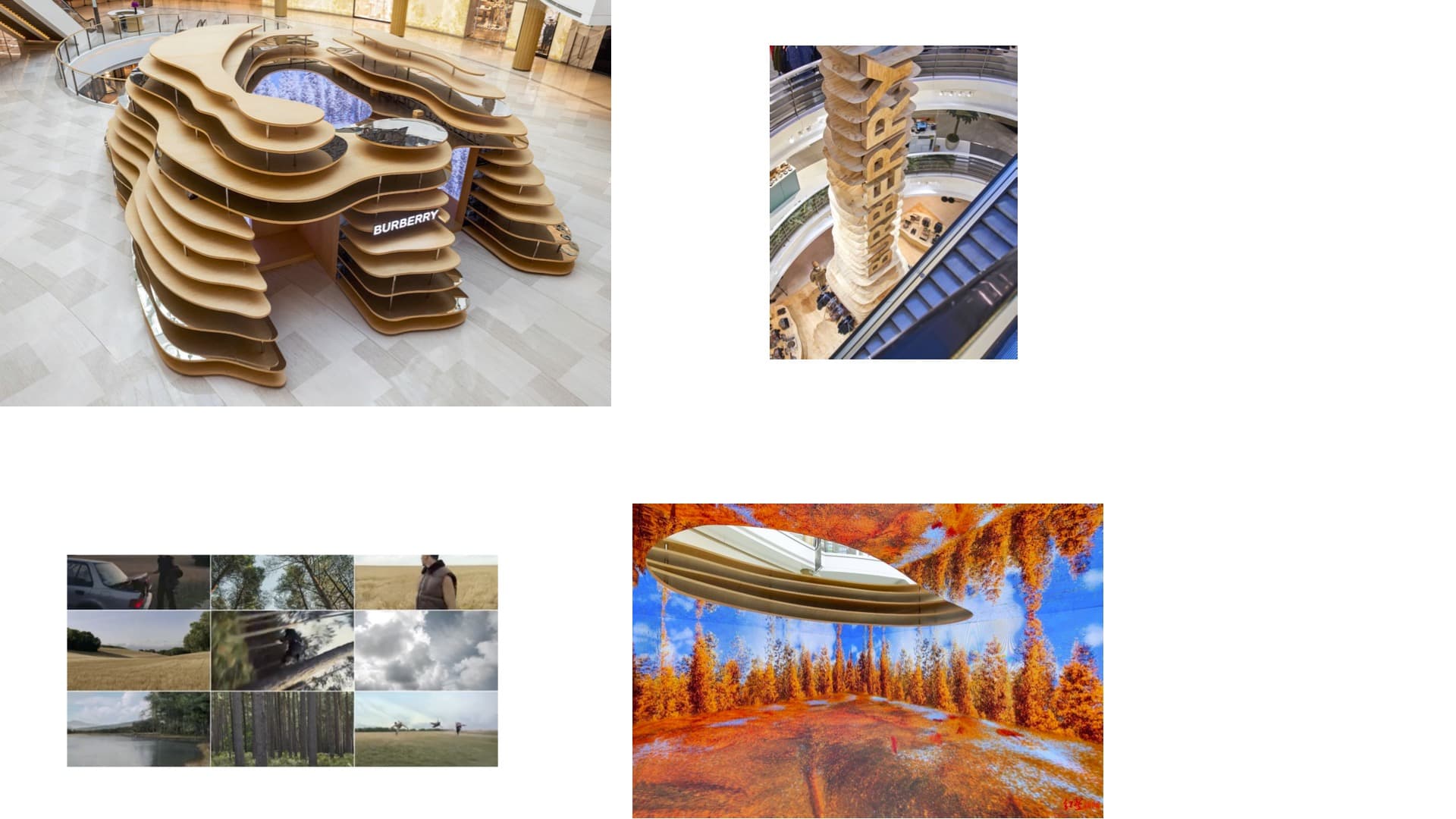

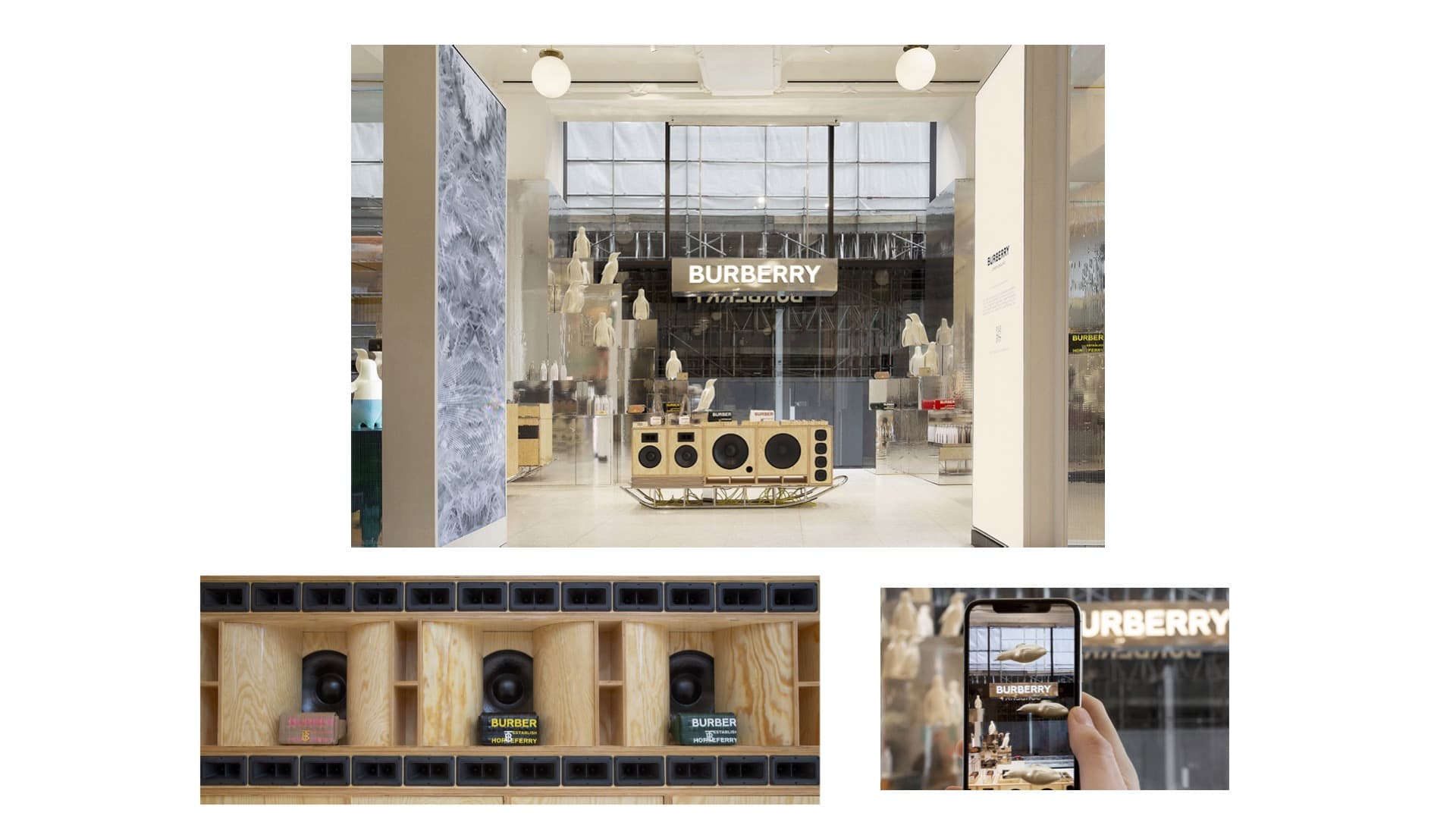

Neil Sharman: Yes, so we were designing for that situation too. At the Burberry Shenzhen Bay store in China, there was this idea of a space that could facilitate that consumer journey. It was really based on this idea, working with the CEO at the time, of having the ability to understand that consumers in today’s market are sometimes much more educated even than the brand about their product. They’ve done their research – on price point, on quality, on materiality, on sustainability often as well. And so the purpose of the space becomes quite minimal in this journey. They can either choose to buy online, or there has to be something that brings intrigue, to facilitate them coming to the physical environment.

So that’s what we briefed ourselves to deal with on that project: what experiences could we create within that space? And sometimes it was thinking what could we do once the store was closed: what could you feed through the glazing? So we had all these ideas flying around, which if it wasn’t for lockdown, we may not have considered.

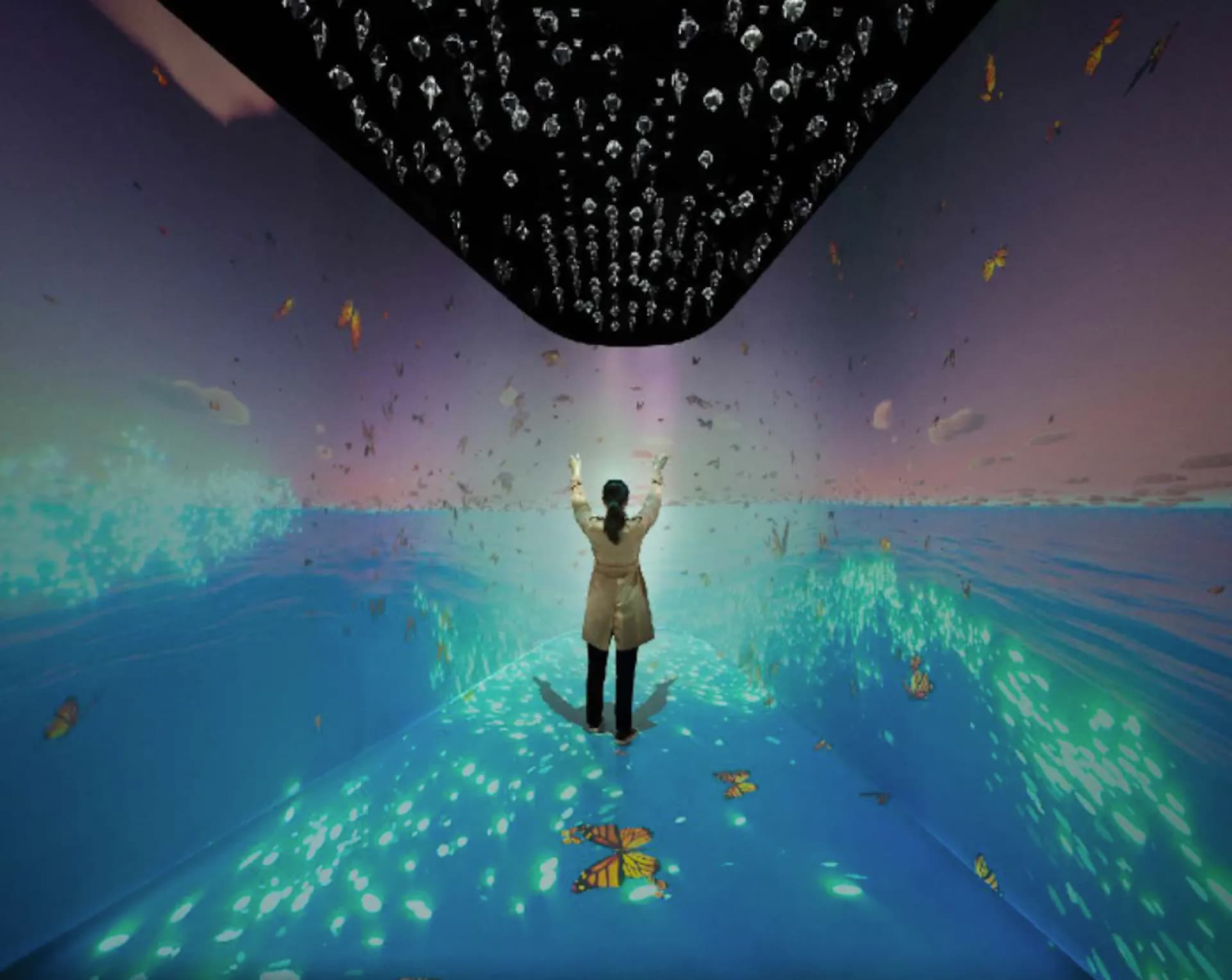

With the space in mind, it was about facilitating that consumer journey from a social or dot.com basis into a reason to join the store – so that could mean booking with a certain service assistant; a room which would be of your choice, but could also be a surprise because you wouldn’t know what door you would unlock; your music; your scent… The idea was to build up a club mentality, so in this instance you actually have a baby foal avatar to dress, which linked to Riccardo [Tisci]’s vision at the time. And the more you dressed it, you would create more status within the store – and that was also transactional, through in-depth analysis of people’s avatars in certain markets, which helped us a lot. And this was a long time before NFTs became NFTs: this idea of creating your own online presence and tapping into that.

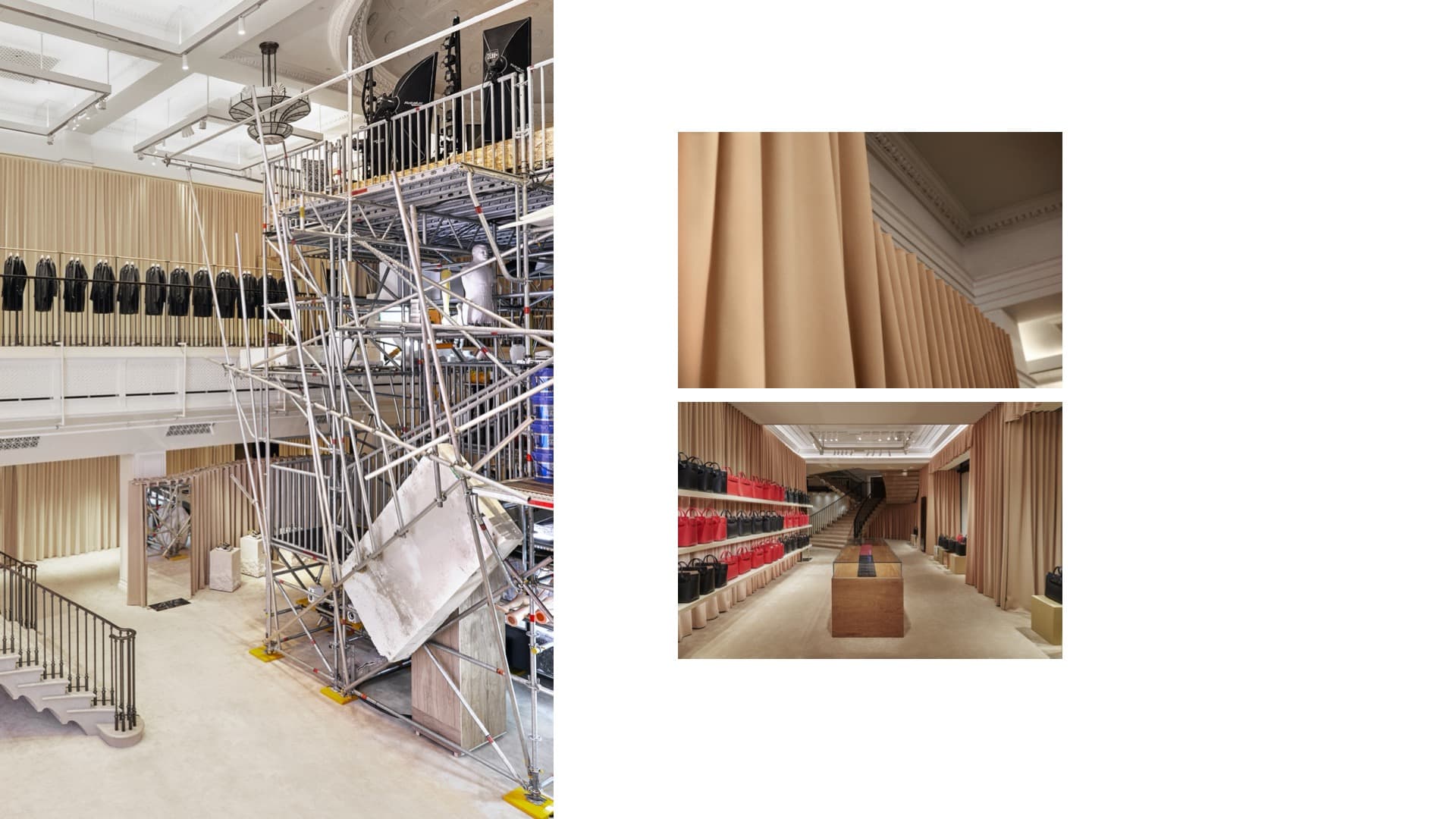

The idea was for the store to be a very fluid, flexible environment. And that meant more spend initially on infrastructure. The space had to flex: it was like a film set, so if people were buying into a certain collection more than others, you might see a change in the drapery or eventually it might be more digital in the front room. It was built to be modular, so you could change the number of digital screens or the amount of plywood: you could take away pieces of the set to make it more installation-led. But while the store was heavily digital, it wasn’t overly digital. As you went through the space, you had all these different experiences. There was also a café at the forefront of the space, but it could also become a library, or a set for a performance, or a talk or a screening.

And that would culminate in a full rain room, where the consumer would enter through a fitting room door, if they had triggered the right moments to get to there, and it would become a 360° moment where you had rain, crystals, interactivity. And this was all built in lockdown, working with a digital company in the States and another in the UK, so I was working on the Shenzhen Bay experience while I was in Kent [UK]: it was all quite bizarre.

Mark Hooper: I’m interested in that mixture of physical and digital. It feels as if having that physical space is still the real draw – having footfall is a much bigger win than directing them to your website. You have a much more loyal, captive audience if you can get them to walk through your door.

Neil Sharman: We did a lot of soul-searching around this ability to understand what physical space means to people in 2023. I think it’s becoming more and more important as the online space gets more crowded and more expensive. People are competing almost like the stockmarket, trying to get recognized on social or Google channels or whatever else.

Mark Hooper: I felt the Makers House, where you helped to create a whole visitor experience around the Burberry catwalk shows for several seasons starting in 2016, was a perfect example of how to really explore the possibilities of a physical space…

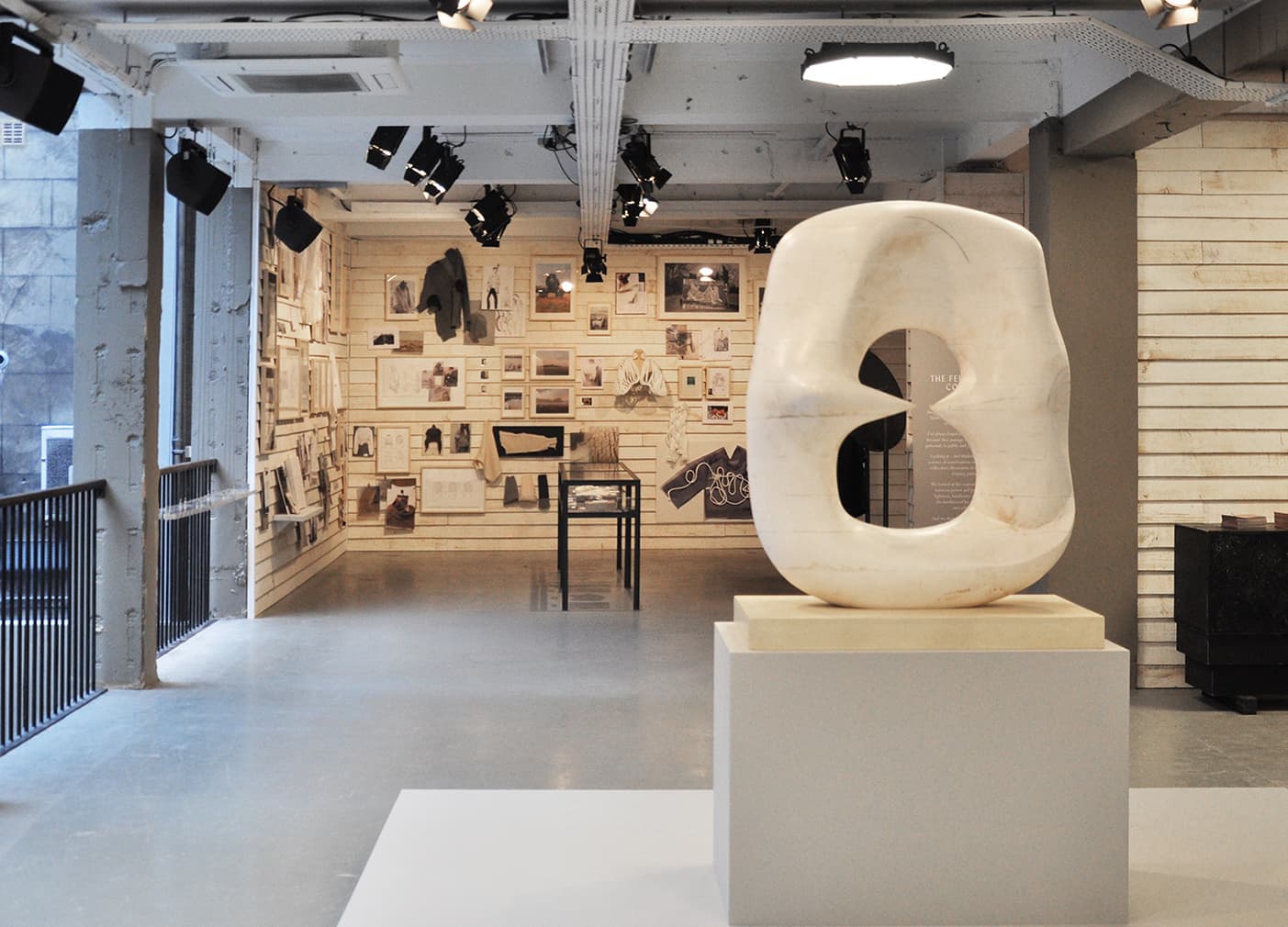

Neil Sharman: To work on that space was phenomenal. That was a classic example of a building with tremendous history that was going to be torn down. And to be able to put a priceless Henry Moore sculpture in there and to do a post collection with a café and an educational hub and to explore the background of the [fashion] show with storytelling – and to bring over 40,000 people to that. We had a whole craft element that we put together with The New Craftsmen and Hole & Corner, which tied into the complete narrative of that collection, through talks and poetry and workshops. It was nothing but an education for us too. And we took what we learned from the Makers House back into Thomas’ café in Burberry’s London flagship store. We remastered the café and it became a really warm, welcoming environment, bring this idea of art and craft and makers back to the heart of the brand. It’s funny how it connected with all these characters in Mayfair too. We’d have people like Bill Nighy in there all the time. It was fantastic.

Mark Hooper: People often talk about content and storytelling when all they’re doing is dressing up their marketing campaign, but with the Makers House, it really felt like lifting the lid on the creative process and inspirations behind a collection; exploring the stories involved in that and the wider world of the brand. It’s like you’ve been let in on a secret.

Neil Sharman: I totally agree. I think when you bring creativity and marketing together with the power of understanding a collection and where it comes from, it really excites people. And that mentality of going behind the scenes; fashion can be very ‘closed door’ a lot of the time. But when you bring people in to your world, it’s quite special.

Mark Hooper: It’s also quite brave and confident to reveal your inspirations and influences in that way. Brands often aren’t prepared to give that information up.

That was what was so special about Christopher Bailey’s time at Burberry. He was very clear of his narratives. And the collections would often go off into these incredible dreamscapes inspired by that. It was remarkable to watch and to be part of that. He had utter respect for the brand, but also about Britishness, which seemed to travel and resonate incredibly around the world – if you think about the growth in the markets both in China and the US.

Mark Hooper: And also if you’re a Chinese consumer, you don’t just want to see the same thing that you can find anywhere, you want a point of difference from a very British brand like Burberry.

Neil Sharman: I was thinking about that cookie-cutter approach to retail and I think people more and more are moving away from that – they want a different experience wherever they go. We certainly see a lot of brands in the luxury market peeling off and doing that incredibly well – people like Loewe, who do a great job of bringing that idea of craft and art into each space, but every space has a different narrative, while still linking to the brand ultimately. It’s interesting to see how sportswear brands like Nike are encouraging people to genuinely participate with the store now, too. It’s about giving something back and thinking about how people interact with products and spaces.

Mark Hooper: It’s been interesting to see how, post-lockdown, realty companies have been rethinking how they should use these empty units, letting brands come in on a short let to use them as more experiential pop-up spaces…

Neil Sharman: Yes. I think there’s a good question for the industry there – is it going to become less transactional? We always tend think of these flagships as mega money-making moments, but actually if you’ve got a key city location and you can get footfall, isn’t that an educational platform you can use for the consumer? And also, thinking more about the Big Idea, the consumer is feeding more into production and quality and design. You see influencers designing their own Salomon or Nike or New Balance product – cutting up trainers or 3D modeling them and sending them into brands themselves. And it’s creating that hype. The classic one was the Nike tie-dye sock that people were making through lockdown – and now Nike are making them for fun now. Etsy had never done so much business! I think that model of ‘can you see people coming’ is important – maybe you don’t make so much stuff but what you do make has been fed into by consumer data. And that can be coming from these physical experiences.

What’s great about all this is you are bringing different people into your space for different reasons. Maybe someone wants to buy a jumper, maybe they want to see the Juergen Teller exhibition, or to get a 3D body scan.

Mark Hooper: It’s interesting what you say about influencers, where they are now becoming genuine creators with a bit more depth to what they do, and consequently adding more value to the brands. I wonder if the tide is turning a little bit more there – or at least that the roles and what is expecting of people is shifting?

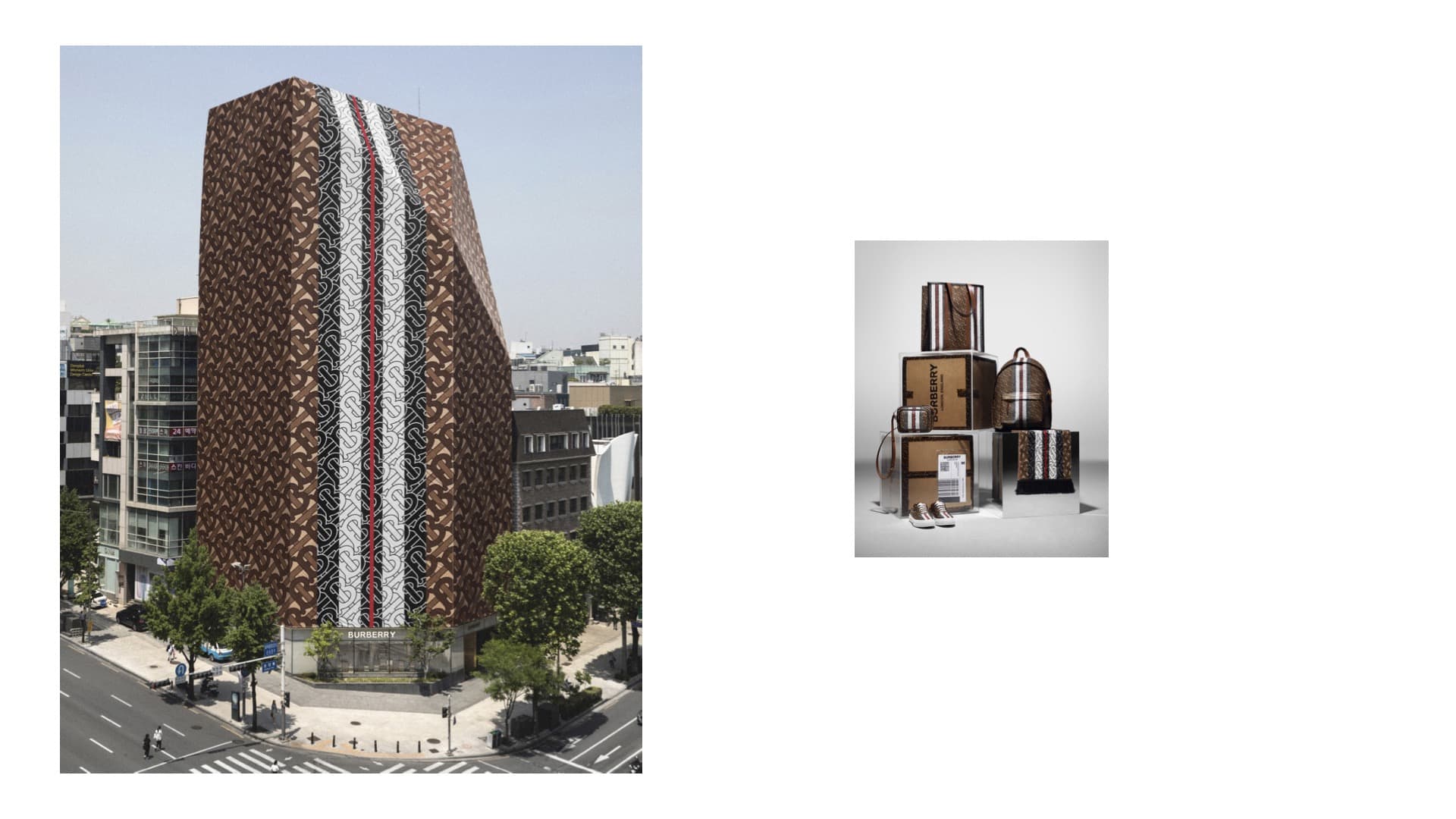

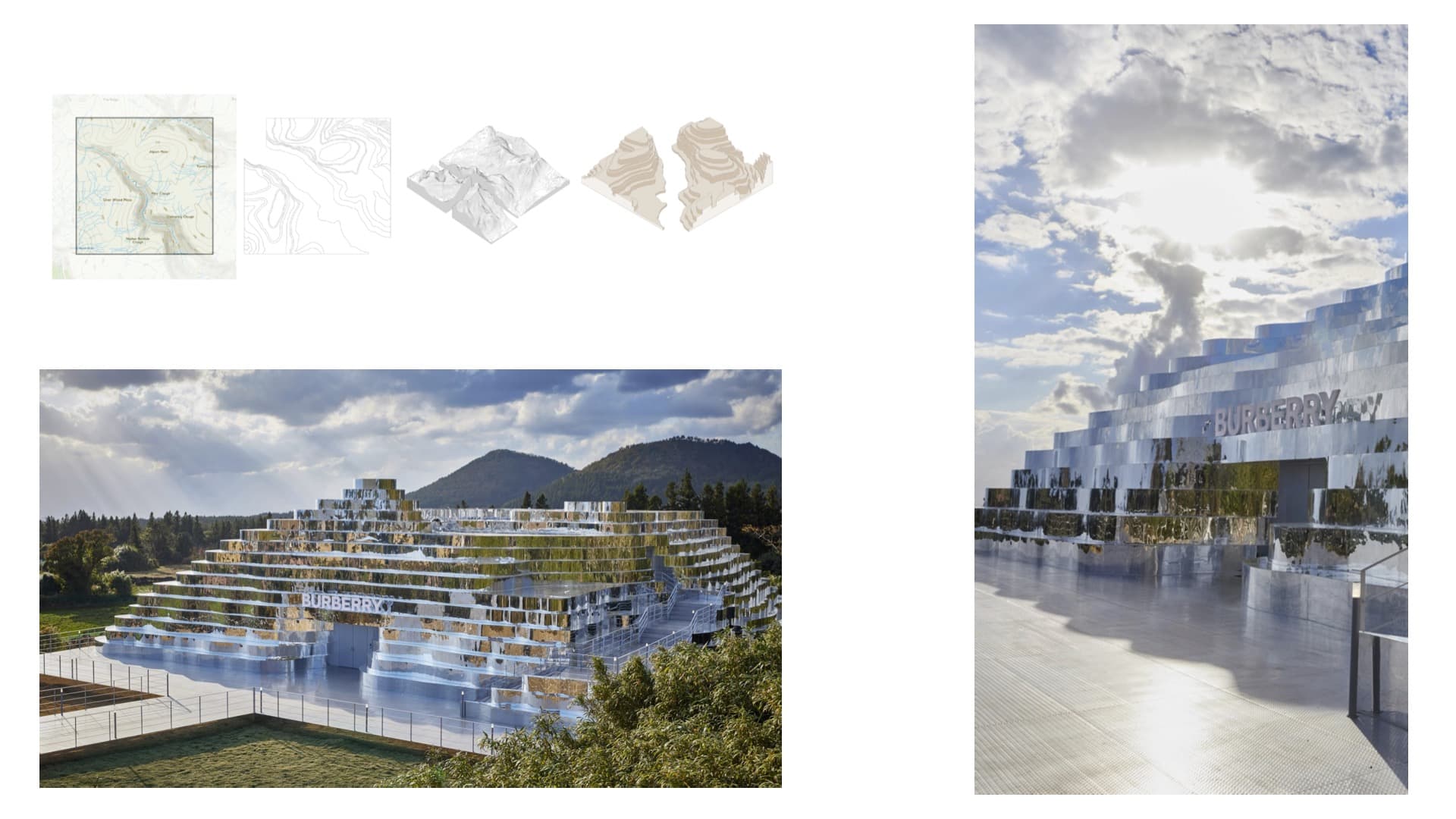

Neil Sharman: Well, I think having been in those big marketing meetings with various brands, where the amount of money being thrown at influencers is phenomenal – it makes me think that maybe you have to go back to go forward. It reminds me of when we were going through the 2008 economic crash, my studio at the time took a project with Dr. Martens in Norman Foster’s Spitalfields development in London. They couldn’t fill the units there, so Dr. Martens effectively came to us with their marketing budget, and said, we don’t see the need to put big campaigns on buses or billboards. We would love to create a pop-up instead. And so we created a pop-up for about half the budget they would have spent on traditional advertising, and they received more pages of magazine press than they had done with their ad campaigns. And it’s like with the Makers House and the other examples we’ve been talking about. Yes, they were designed for engagement, and people were still taking a lot of pictures of themselves, but I think going back to physical is perhaps the answer rather than paying a lot of people to drape themselves in your clothes over social media. It’s a simple application and it’s very cost-effective. But that doesn’t mean it has to be small. At Burberry we did this massive pop-up project that we built on Jeju island in Korea. It was a digital experience, but we built this mega structure that was fully mirrored. Or we took over a ski lodge in China. They both got a huge amount of press.

Mark Hooper: And it’s an interesting story isn’t it? Having worked most of my time on the other side, looking for editorial features to run in the fashion press, all you want is a good story. And a mirrored island in Korea is a better story than a pretty person wearing your clothes on Instagram.

Neil Sharman: Exactly. I think bringing that edge of theater and performance is what can make some brands feel really new unique. And giving everyone a different experience. And the question is finding a way to do that in retail. Something that’s all about discovery, customization and a bespoke service. When you talk about those huge malls in China, they demand newness from the brands. And you need to be testing that newness before you get it into the mall. But it is also about being less strict on the idea of commercialism, and instead focusing on something that can really resonate and give back.