Our Talk with the King of Fashion Digital, PASCAL DANGIN

Images are the most visceral and emoting of storytelling forms. And within their tales, nuances make the difference between reality and dreams. For over the last few decades, Pascal Dangin has been fashion’s visionary dream-maker, leading his artisanal eye and hand to create many of fashion’s most iconic images and influential narrations.

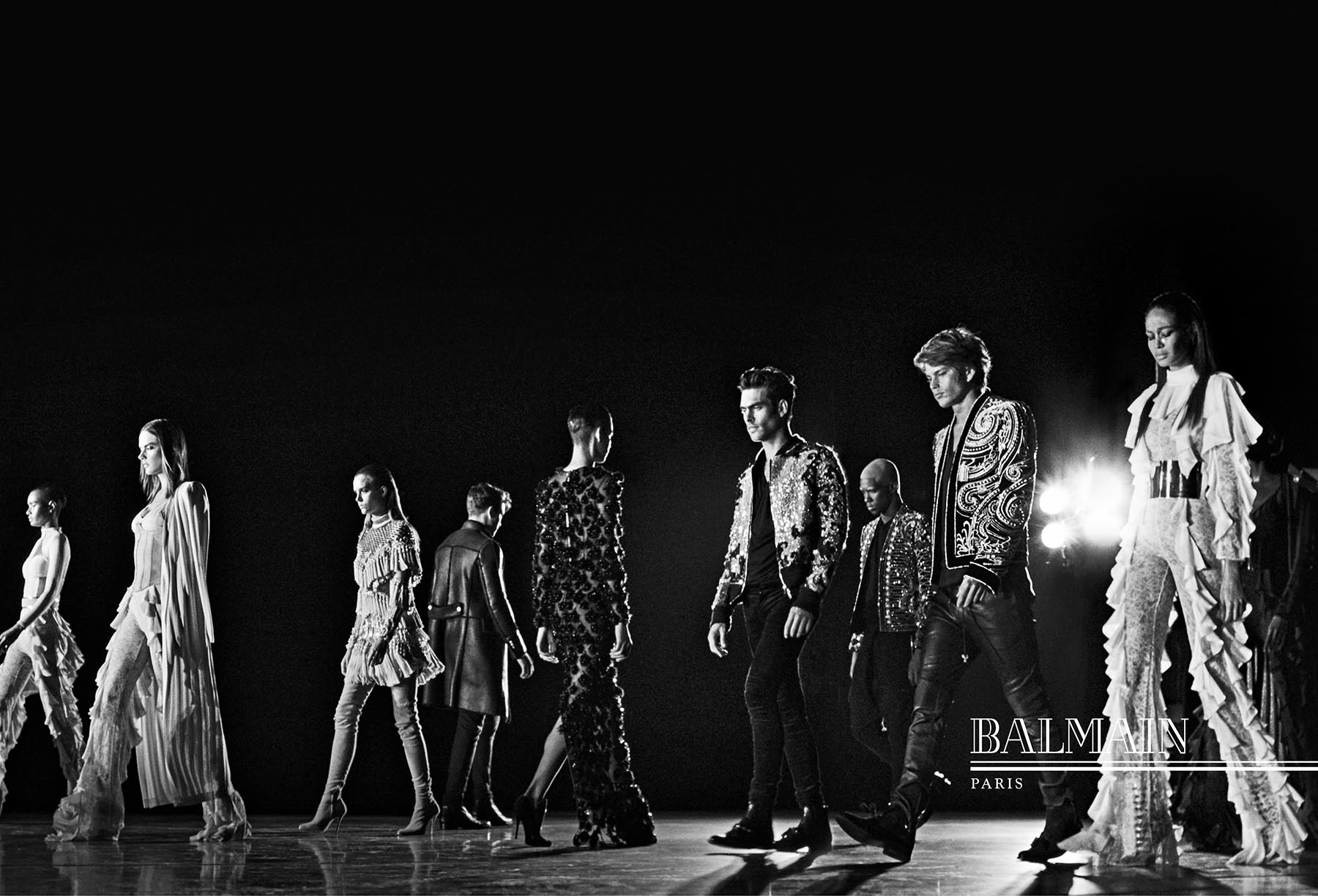

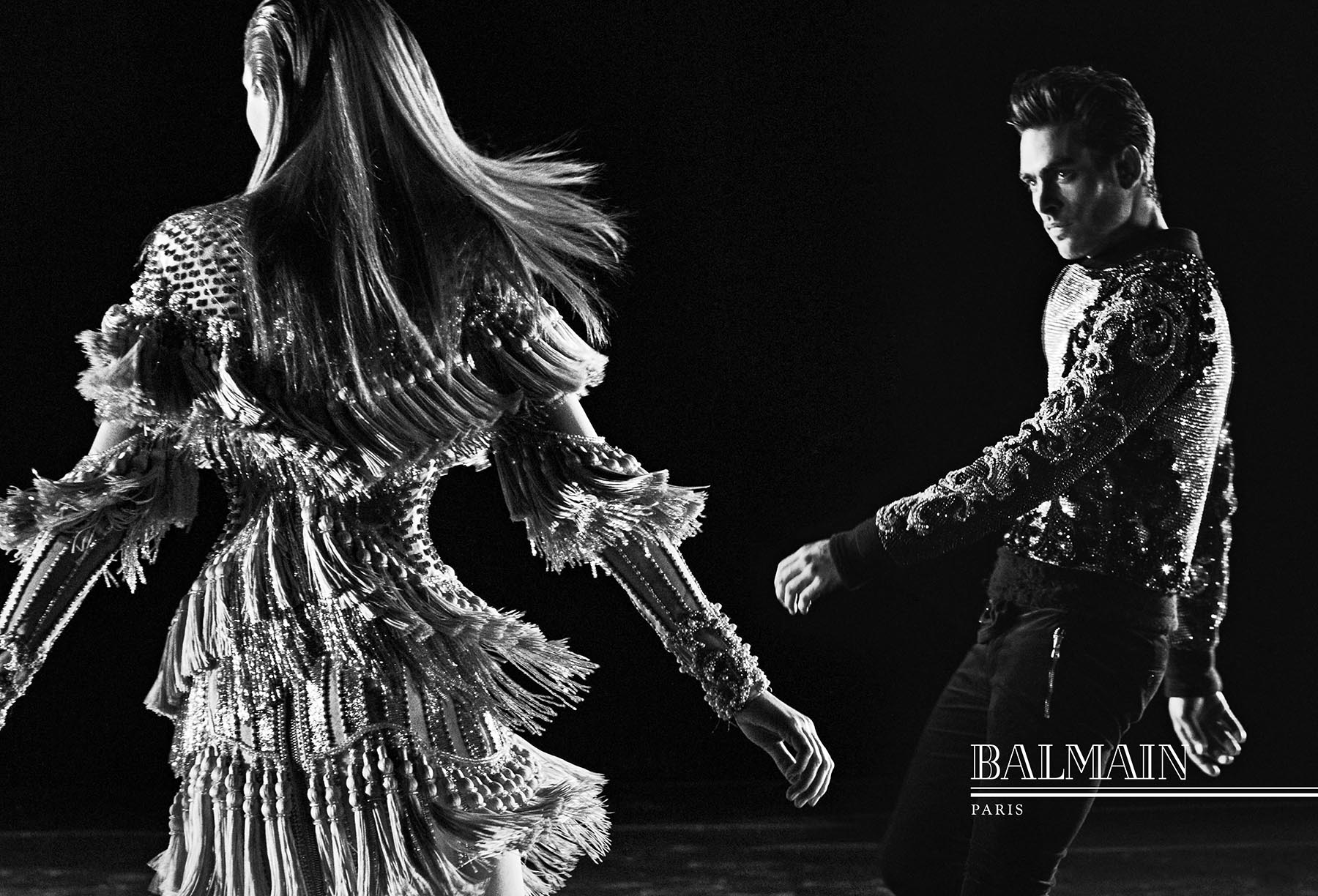

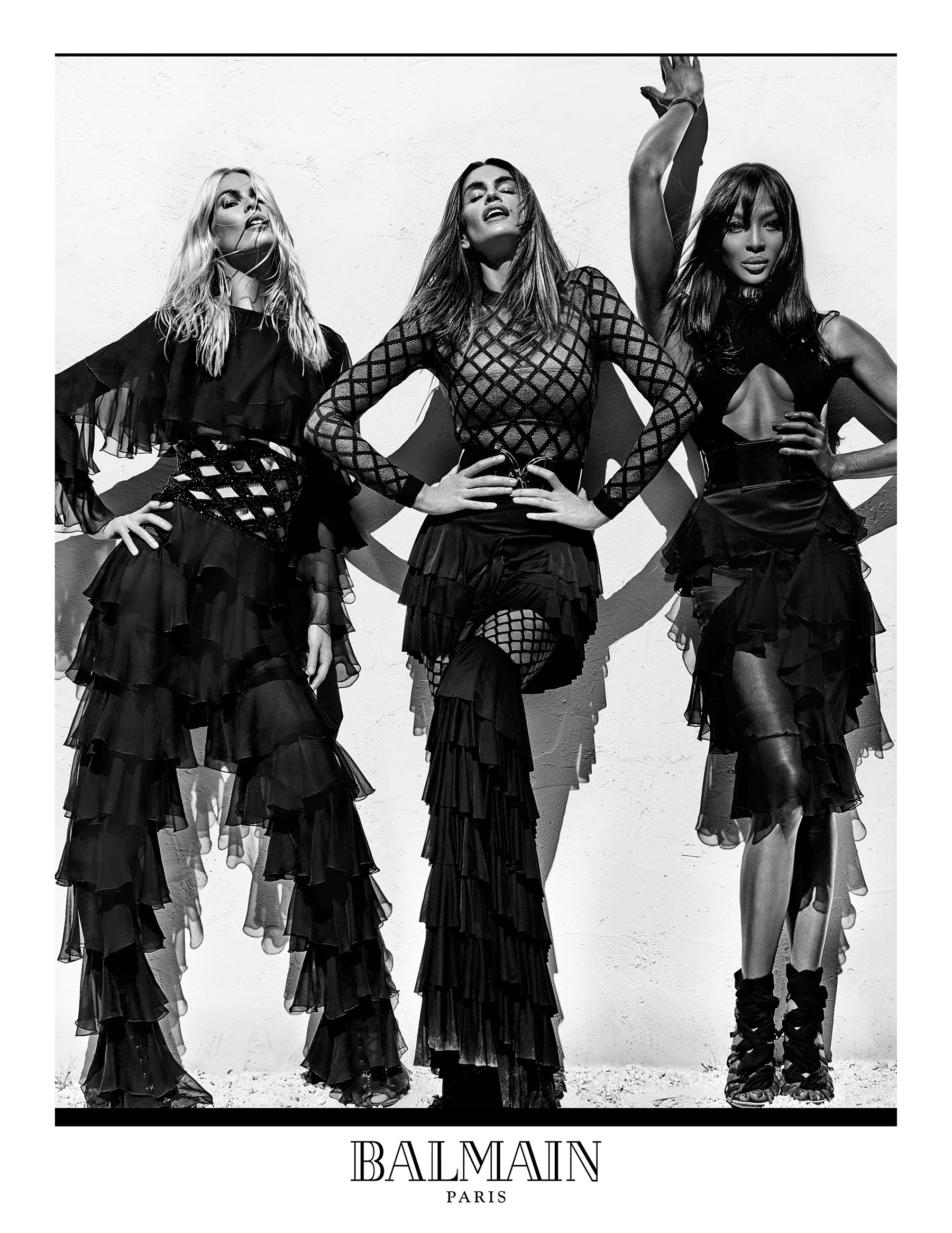

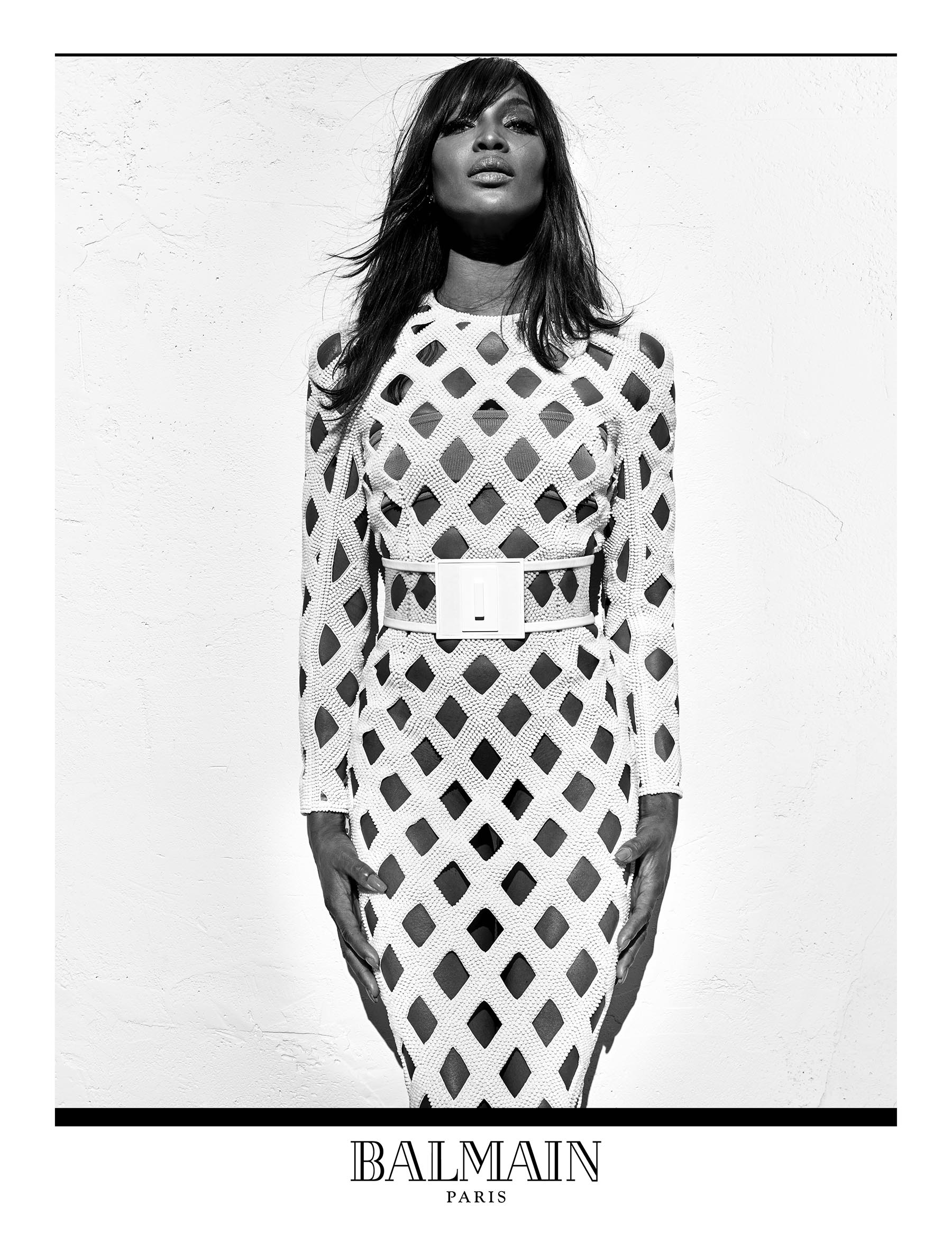

Congrats on the latest round of amazing campaigns and the recent Balmain video. We’ve chatted a few times about the art of imagery but never about your beginnings. How did you find your way into the industry?

I started as a hairstylist, or actually as a shampoo boy – doing shampoos and hair coloring and learning how to make someone look beautiful. The salon was a great environment to learn about aesthetics, taste and psychology. We always say that a woman tells everything to her hairdresser. So I developed a lot of those skills in the early days. I started at 15 by knocking on the door of a salon that was looking for an apprentice. I just went in and said, “I want to be an apprentice.”

Where was that?

In the 15th district of Paris. I remember walking on the street and literally just turned my head and saw the sign on the window. I had dropped out of school and was not really familiar with Paris. It was very foreign to me – the concrete, the people. I grew up in the country.

I was very good at drawing, so my mother thought that I should go to an art school to learn. I went to various schools to test to be accepted and was accepted in some of them, but I just didn’t feel like I wanted to be drawing bottles and still life. It is not that I had an opinion about it, but because I didn’t feel like I wanted to be in school. I had a strong reaction against school. I suppose my childhood did not create a proper foundation for learning, or at least listening to adults, which had more to do with the fact that I did not trust adults.

But you must have been listening in the salon.

The difference is that when you’re a fifteen-year-old straight boy, the only thing you’re thinking about is how you are going to evolve as a man. It obviously opened an entire world for me that I had no idea existed. Pair that with the love of being able to look at someone and realize that you have the power to make them feel better about their image. Because I looked at their face in the mirror and the mirror, really, was the genesis of the screen. Images back at that time didn’t exist on screen. We didn’t have the computers, watches and iPhones. But the visual of someone’s reflection, really – without knowing it at the time – was the screen for me. And looking at the screen has always been a fascination of mine. I’ve always loved synthetic image in that way.

So how did you transition from the mirrored screen to the computer screen.

After a few years learning the craft of hair cutting and everything that has to do with biology and chemicals, I realized that there were fashion magazines that I didn’t know existed. In the salon, I would go through them and see credits for hairdressers and think, “This is cool, I would love to do that.” They would be on a beach in the Bahamas or on Mauritius or on a mountain or in Moscow and I thought, “I want to do that, I want to be there.” So the salon quickly became too small of a world for me.

I don’t even know how it happened, but at 18 years old in Paris, I found myself backstage at a lingerie show. I had arrived with my brushes and my hair dryers, not knowing what I was stepping into, and when I went backstage, these gorgeous women were all over the place in lingerie and I thought to myself, “I really like this job.” [Laughs] I was obviously very seduced by that world. So one thing led to another as a stylist, and then I joined a team of Jean Louis David. At the time, he was very proficient.

So I found myself very quickly doing runway shows with Yohji Yamamoto and suddenly I was flying to Tokyo, and this whole new world opened to me very quickly. From the time I was 18 until I was 30, my world was hair, hair, hair, hair; fashion, fashion, fashion; makeup, makeup, makeup; photography, photography, photography. I really fell in love with photography at that time.

Meanwhile, I’m watching and learning – having not been educated at all – and I began reading books. Evidently, I didn’t speak any English; so every morning I went to the cafe with The Herald Tribune under my arm. I had no idea what I was reading. I thought that word ‘people’ was pronounced pee-o-ple. [Laughs] I was learning English in my own way so I could communicate. Because obviously I realized everybody speaks English and models are from New York and without it you cannot communicate. I watched a lot of movies and read books and I finally got my way around English.

Were there ‘pee-o-ple’ who helped you along the way?

To teach me? A little bit. But really, most of it was thinking I need to communicate and I need to speak to people and I need to learn that. I need to overcome that lack of knowledge – basic knowledge.

So you self-taught your way into hairdressing and into speaking English, as well as finding yourself in an avant-garde moment with Yohji Yamamoto. What inspired that curiosity?

First of all, the circumstance in which I found myself, but then also I really started to fall in love with fashion, clothes, and the magic of transformation. One morning would be this way, the evening would be that way, and I learned about the various psychological characters that people are able to create for themselves.

When you grow up within a normal environment, or I would say external environment, there really aren’t games about becoming or projecting a different personality, you just adapt to the mold in which you grow. Fashion became theatre. Fashion became a playhouse. ‘How do I become a seductress? How do I become revolutionary?’ – and at that time, I also started to learn from the punk movement. Of course I was born in the ‘60s so I was young, as this was the late ‘70s and early ‘80s, but it was very close to punk. I often went to London from Paris, so I learned about what punk meant – the statement of changing who you are physically to project a different image. That, to me, was fascinating.

Have to fast-forward a little bit as I see that transformation and risk in your work now. Do you feel the Punk Movement has stayed with you and influenced you even to today?

Although I didn’t have a mohawk, I understood social class, the fabric of society, and why they did what they did at the time. And I was more fascinated by their heart than their music. Honestly, I never really dove into the punk music so much. My sensibility in music is very different, but I did like how they forcefully, and I would say peacefully, raised their hand and said, “We exist and we want something different.” I think they broke a lot of barriers, and the idea of breaking barriers, pioneering, being the first, probably has some influence on me in my career. I don’t specifically want to be the first, but the feeling that there’s no limit has a fearlessness that comes with it and says, “Why not?”

So let’s talk about that limitlessness, because you transitioned from hair to a new technology that began at that time and you were right there on the forefront. When did you first start to touch the computer?

Well, I think I was very geeky. And again, I want to say, very importantly: I’m like you are, a digital immigrant. I’m not a digital native. I didn’t grow up with it so I had to learn about it. It’s different today with kids who swipe and know how to set up an email account by the time they are five years old. I looked at computers often and I actually learned with DOS programming – basic DOS programming. Don’t ask me why I was able to do that, it’s just the curiosity that I have always makes me want to understand why things happen and the reason for which they happen. I’m never satisfied by pressing a key and having something happen and not knowing how it happened.

I’m picking up a pattern of tinkering. You’re an explorer in the process. Does that have to do with being self-taught?

Yes, I think it is part of the decision to pick up The Herald Tribune and start reading without understanding a word.

So you applied that to technology?

Yes. I remember I was on vacation in the Bahamas and I had finally gotten my hands on the new Toshiba laptop that was the first with 256 colors and a program called Paint. An image appeared and the fascination for me was to see images on the screen, which had a very low-density pixel. It was really pixilated. I just was fascinated by the fact that you could just click something and change the color of it. I would select the blue of the space around say an astronaut and I would make it red and be like, “Wow, this is very cool.” I spent my entire vacation just playing around with this one astronaut picture. I recently went back to this hotel on vacation and I went into that room and told my kids how this is where dad started his story.

There is a Jack White song about a successful person who is always striving to get back to that little room where all their creativity started. There’s always a little room in everybody’s story.

Yes, there’s always a little room. I think that from that moment on, I never let go of the concept of an image on screen although it was years later that my fascination for image manipulation, my fascination for understanding photography, began. Being and talking with photographers all the time, you start to pick up on things clearly. Even in the early days, I would always say there’s got to be a better way to do what we do.

When did people start coming to you for that better way?

One thing we have to remember is photographers at the time did not have much control over their images the way they do today. Photographers used to select the pictures, make ‘work prints,’ and make the final print; they would have some hand-retouching touch-up to do, but it was very limited. What happened is those prints would end up going to the magazine and things would get manipulated there by the art directors of the magazine. Cropping, cutting – you name it. Then the picture would come out 3 months later in the magazine and the photographer would have no interaction with it. It was very much like, you took the picture, now we do layout. It was frustrating for the photographers.

So I think what I saw was a white space – I’m a photographer’s lover, I love those guys, I love what they do, I love their mind, I love their heart, and as a support to them, my first inclination was to help them control that process. It was socially, de facto, reversing the industry, if you will, by saying, “Okay, now the photographers are going to pick the 10 pictures for the 10-page story,” not 50, because they do not have the time to do 50, they only have the time to do 8 or 10. I would say, “No, no, you have to make your choice now, let’s not ‘figure it out later’ – there’s only one cover, there are only 10 pages, so let’s figure it out now.” I literally bridged photography and lithography into one link. Of course, reproduction was a whole different story than photography. And reproduction was at the end of the process with pre-press people, who didn’t understand photography and certainly did not operate under the same rule of actual contrast – the word “contrast” in a pre-press room has a different meaning than it does to the photography crew.

So I think what I saw was a white space – I’m a photographer’s lover, I love those guys, I love what they do, I love their mind, I love their heart, and as a support to them, my first inclination was to help them control that process. It was socially, de facto, reversing the industry, if you will, by saying, “Okay, now the photographers are going to pick the 10 pictures for the 10-page story,” not 50, because they do not have the time to do 50, they only have the time to do 8 or 10. I would say, “No, no, you have to make your choice now, let’s not ‘figure it out later’ – there’s only one cover, there are only 10 pages, so let’s figure it out now.” I literally bridged photography and lithography into one link. Of course, reproduction was a whole different story than photography. And reproduction was at the end of the process with pre-press people, who didn’t understand photography and certainly did not operate under the same rule of actual contrast – the word “contrast” in a pre-press room has a different meaning than it does to the photography crew.

I eliminated this difference, if you will, and I fought like crazy in the early years over, “No, no, you’re not getting a print, you’re getting a file.” So then I was on the fast track learning about separations and colors and dots and ink. I found this Indian guy who had this really great press and I was printing all night long, tons of images with him, doing shot after shot, literally, for months, figuring out exactly how to achieve this – and, again, learning. I was trying to find a better way since there’s no CMYK in photography. Why were we working in 4-color? I thought let’s work in 3-color and convert later. This discussion would end up being a technical thing, but forcefully giving control to the photographer. I think, at the end, the bottom line was really about that. It gives them the freedom, essentially, to create.

But when you started, you didn’t just change the game by empowering the photographer with the editing process and then the creation and then the selection, but you also empowered them with the magic to enhance their photography in a way that could match their imagination.

Yeah.

That skill set is unusual and is like the hand of an artist. Did you always think that hand was there, or did it develop?

I think somewhere it has probably always been there. I was always very sensitive to the placement of objects in a room. I’m very sensitive to where things should be and it kind of hurts me if I don’t feel like it’s right. I have this pain, this physical pain if it’s too dark, if it shouldn’t be that dark or shouldn’t be that light or shouldn’t be that red or shouldn’t be that blue or that angle or that position – if it’s not right – and I have no way to explain it, honestly. But if it’s not right, it’s not right – it needs to be changed.

Nature is the only thing that I don’t touch. I like nature as it is and I learn from nature a lot.

But you must change nature quite a bit in images.

In the work that we do, yes, of course. But like I say, in general, I’m inspired by nature and I don’t touch nature to change it. But I’ll cut grass exactly the way I want it to be cut. I’ll cut bushes the way I want them to be cut, too; I’m always surprised as to why others cut bushes the way they do. For me, it’s always volume, it’s all related to volume and position and an eye for detail.

Do you know immediately when you look at a photograph?

Yeah. 14 milliseconds… because I’ve done it for hundreds of thousands of hours.

And when you started, you did most of it yourself.

Not just when I started, but for a very long time. Still, to this day. The difference now is when I have an idea, I execute it, I create it, and I don’t need to rely on anyone to do it. And when I have a very particular idea about what I want – whether it’s in editing or music even, or how it’s graphically done – I’ll do it… I have my dark room still.

So let’s talk about the darkroom business, how did that all evolve?

So let’s talk about the darkroom business, how did that all evolve?

I took a reject negative of a photographer who I was on set with, and I said, “I think there is something there, I think I have a way to make prints that are new or different and I’d like to try it, to see what happens.” So he gave me a negative, and I did what I had to do. But it wasn’t as fast as all that – for three years before that I had run a factory out of my apartment doing C-prints, and I had an eye for chemistry and digital and scanning and you name it. I did this one image for him, and I gave him a beautiful C-print Fujiflex two weeks later. He asked me, “Where did you do that? Where did you get that?” I said, “Oh, I just did it because I wanted to learn and understand.” I never really even thought of it as a ‘business.’

I remember him saying, “Oh, I wish I could do this…” So I did all of the things he wished he could do. He said, “Could you do that for the rest of the pictures?” and I said, “Yeah, it’s going to take me some time, but…” and I did. He gave me the story and the negative and I made it and that’s how it started.

When did you found Box Studios?

Soon thereafter. I think, organically, there were a few more stories here and there. I obviously had no money, so I did hair. At that point, I was no longer interested in Vogue covers or hair magazine covers or prestigious images, all I cared about was making money. I would just go into catalogs, taking a large number of pictures, which was good pay but did not require much thinking. I used to be on set all the time with my own computer, rebuilding images. So basically I would be on set during the day and work at night; I did that for many years, where I just slept two hours a night and just kept on.

It’s interesting that you set up the business early just to drive the economic engine. You toiled behind the scenes for many years doing that and then came out front as a creative driver. How did that come about?

Well, I think it was gradual. I think it happened for many reasons. One of which was, that I didn’t think that the quality of work I was getting was as strong as it could be. I started not liking the pictures. It started to become too generic, it started to lose its intent. I had, of course, created the addiction – where people would rely on me for taking care of all their pictures. But what we did on the tail end shouldn’t be at the expense of the creative process up front. And if the intent isn’t right, if the ‘let’s fix it later’ approach takes over the process of actually creating something, then you’re never going to have a good photograph. And it’s in everything – it’s not just what the setting is, it’s the light, the calibration of the film versus the light, and so on and so forth and everything.

Digital has created this grey area with everyone starting to feel a little bit like, “Let’s just do it in post.” I didn’t grow up with post; I grew up with, “Let’s define what it is that we want and let’s build it.” And most of the photographers had it that way as well, but with the economics changing, there was the ever-increasing pressure for time. You know there are all of those primary things that just push the envelope to produce content. And it got to a point where content became king.

People like Fabien and I used to spend hours looking at dots and percentage of ink trying to determine how we can print better. The craftsmanship of that was great.

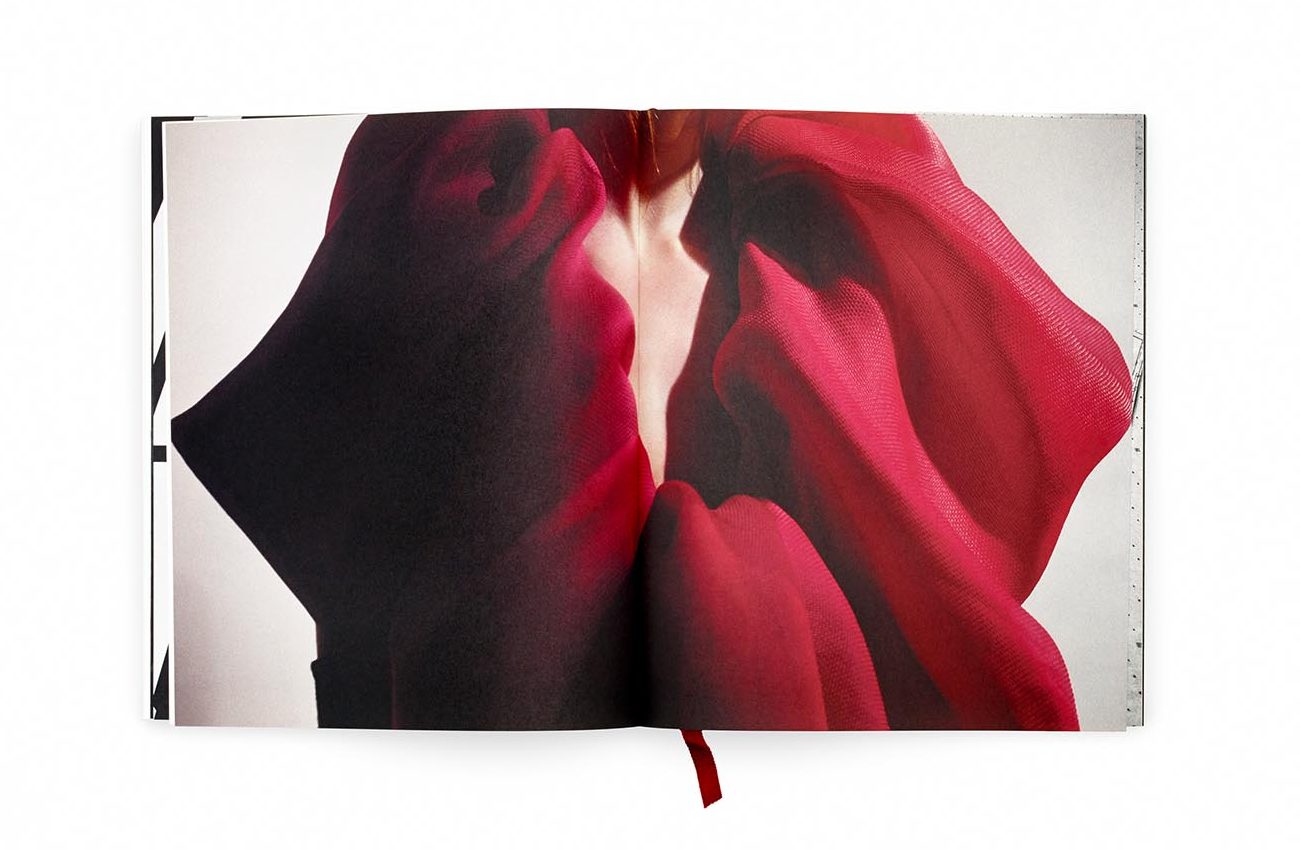

So after still, print and bookmaking, I turned to film. I wanted to learn about movies and I wanted to do a feature film, and there was a great cinematographer who sadly passed away, Harris Savides, who loved my work as a printer. He asked if I could do a film with him. I did this film called Restless, which was great, and then suddenly I was in the movie world and doing movies. And, you know, I could have done that for a long time, but I paused and thought, “I have spent the last 15 years in the dark, in front of a small screen. I’m not sure want to spend the next 15 years in the dark in front of a large screen.” The concept of moving images is amazing, and I’m in love with the process. But I need to express my ideas, I need to move and change the paradigm of image creation.

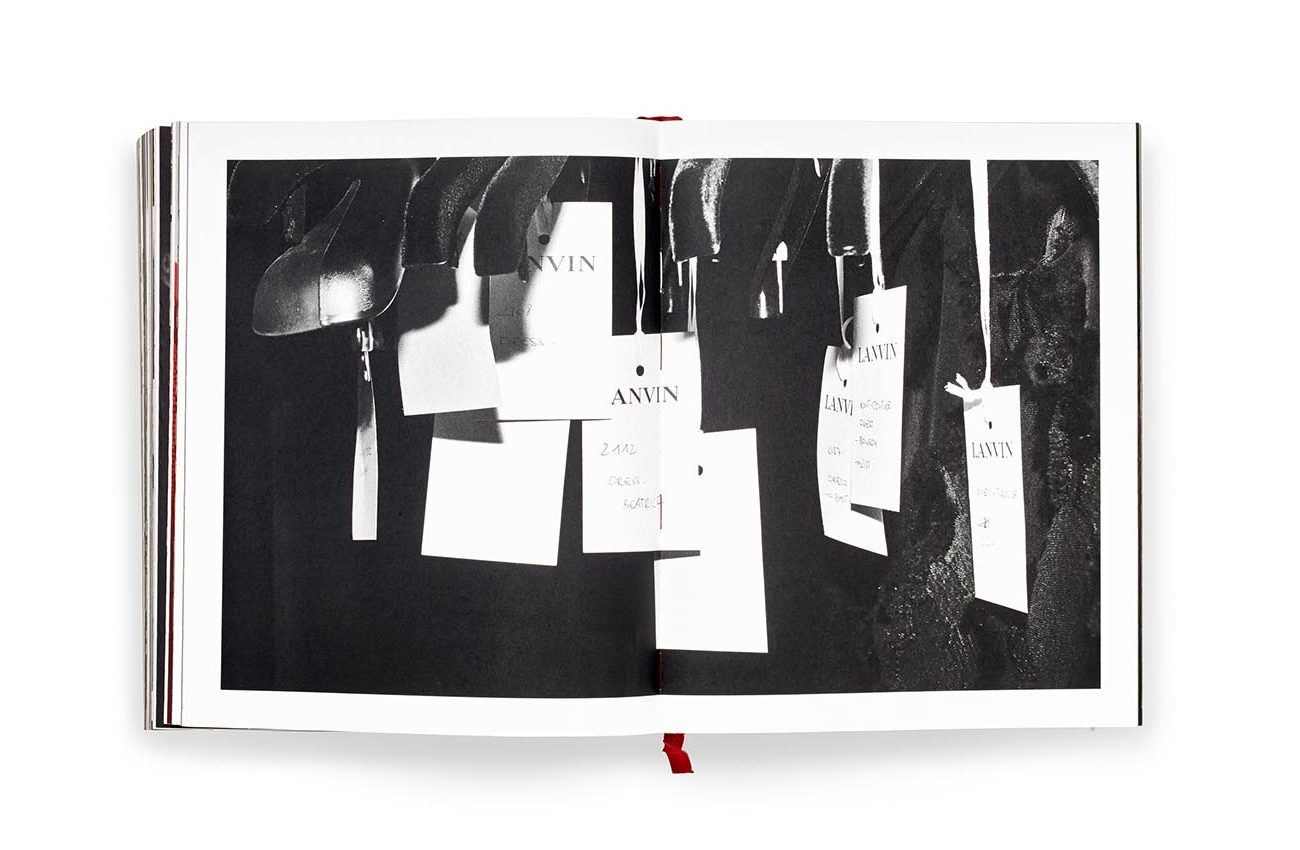

Then Alber Elbaz called me up, because of my book-making knowledge and various photographic book ideas, and said, “Hey look, I’m trying to do a book. I’m not seeing anything I like, can you help me?” So I worked on the book and created this element. We produced this very beautiful product, for which I did the conceptual work, even the editing. It was the beginning of creative direction.

So, Alber was the first person who took a bet on you, with regards to being a creative director. What was the follow-up to that?

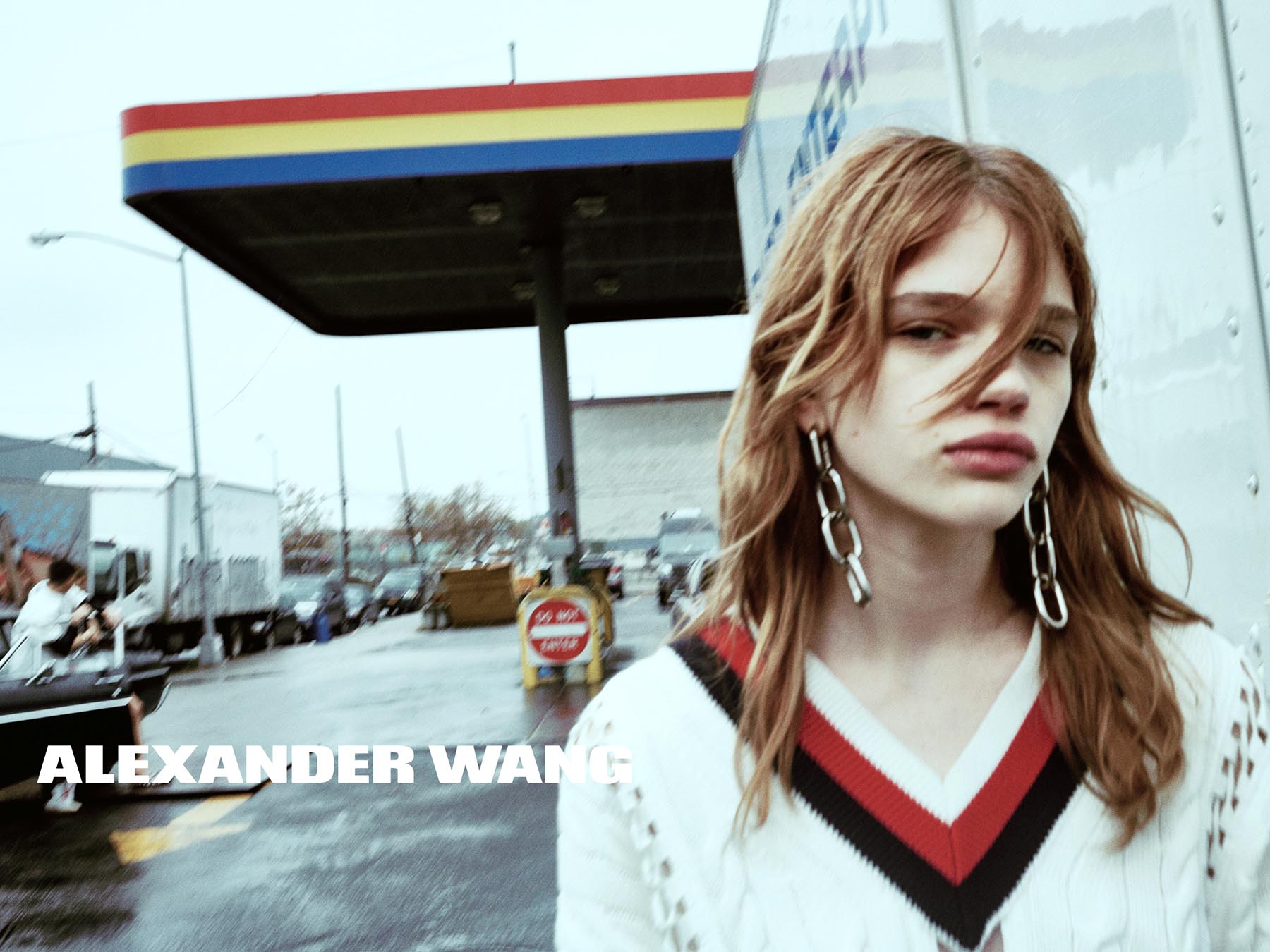

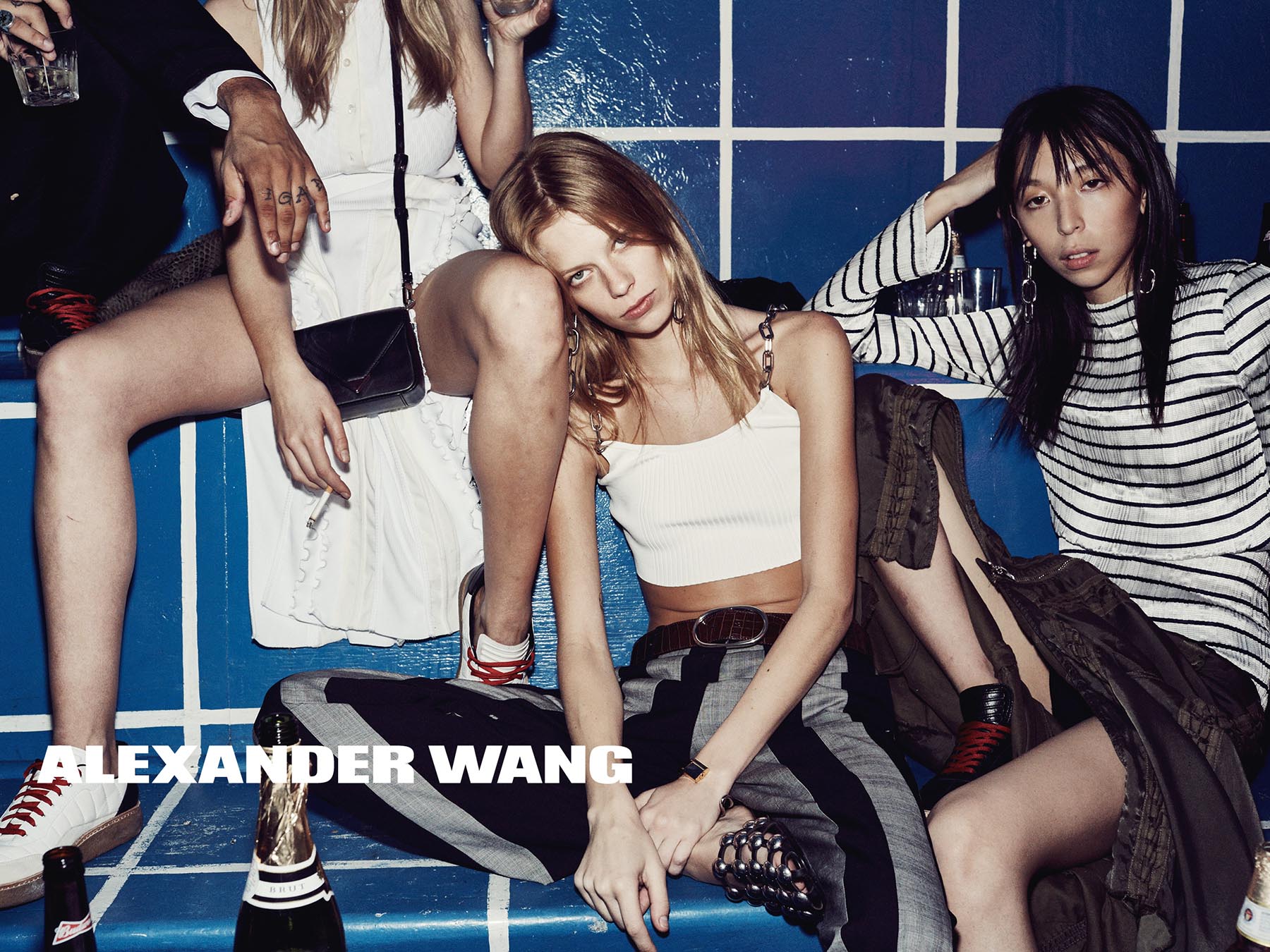

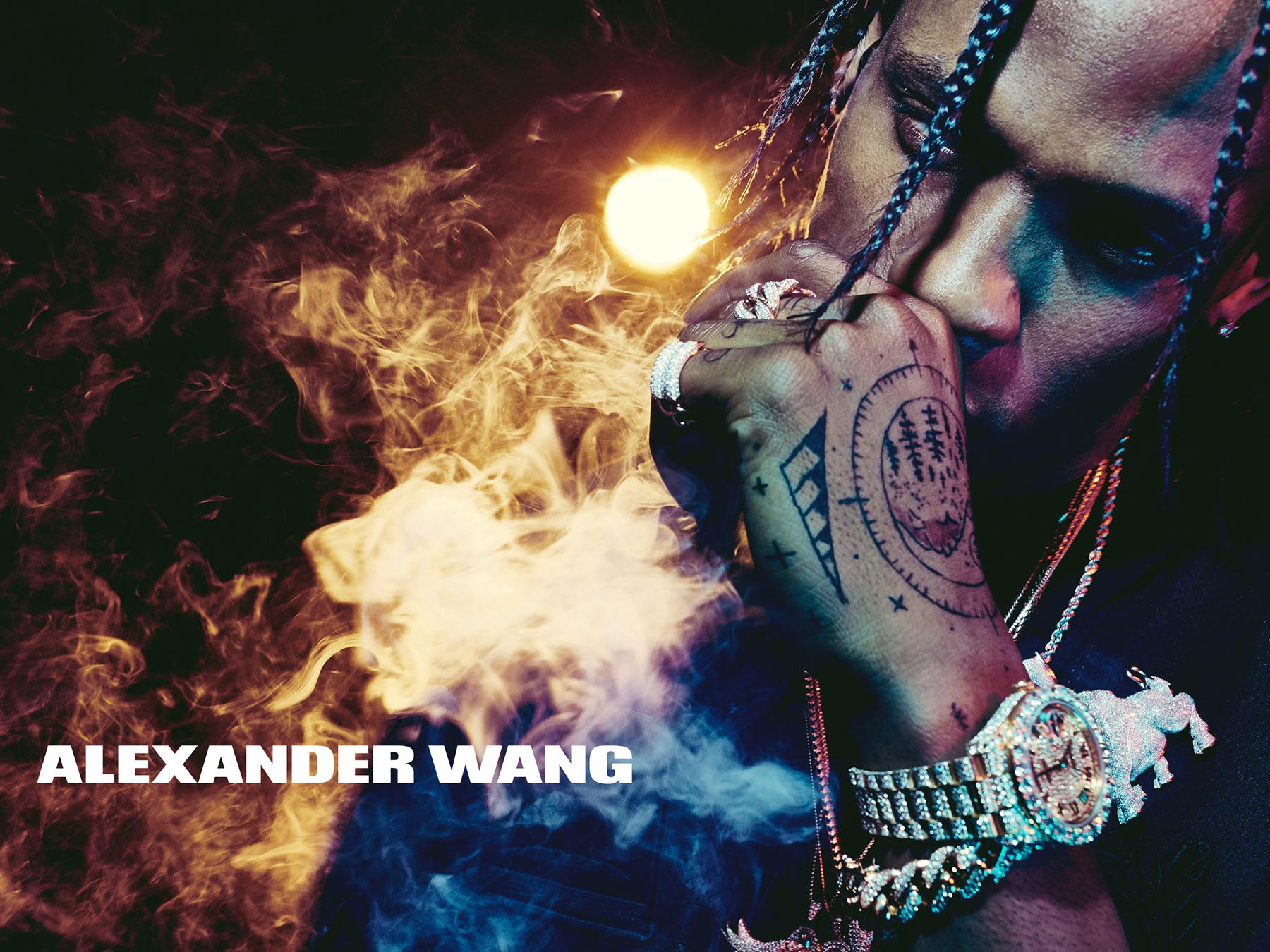

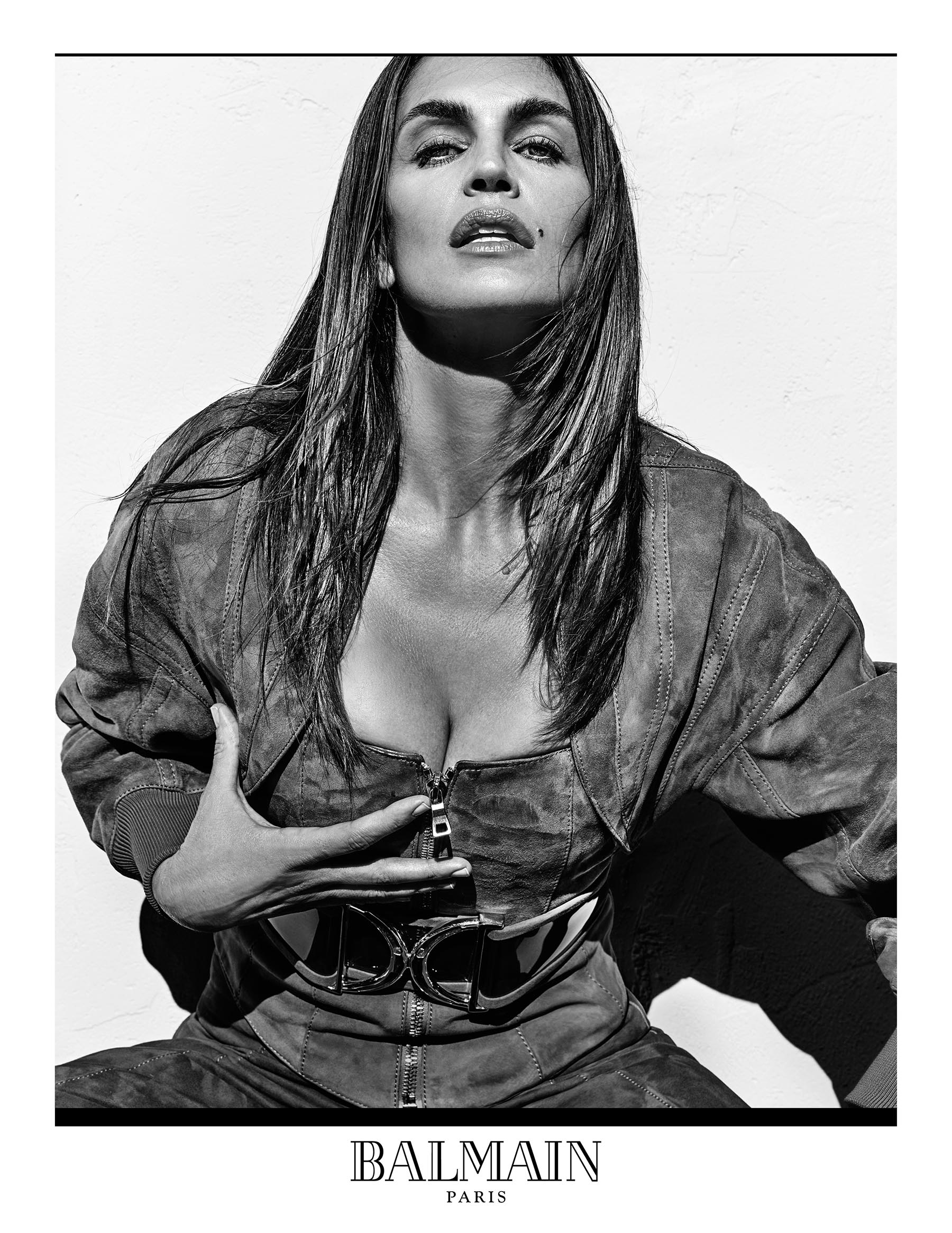

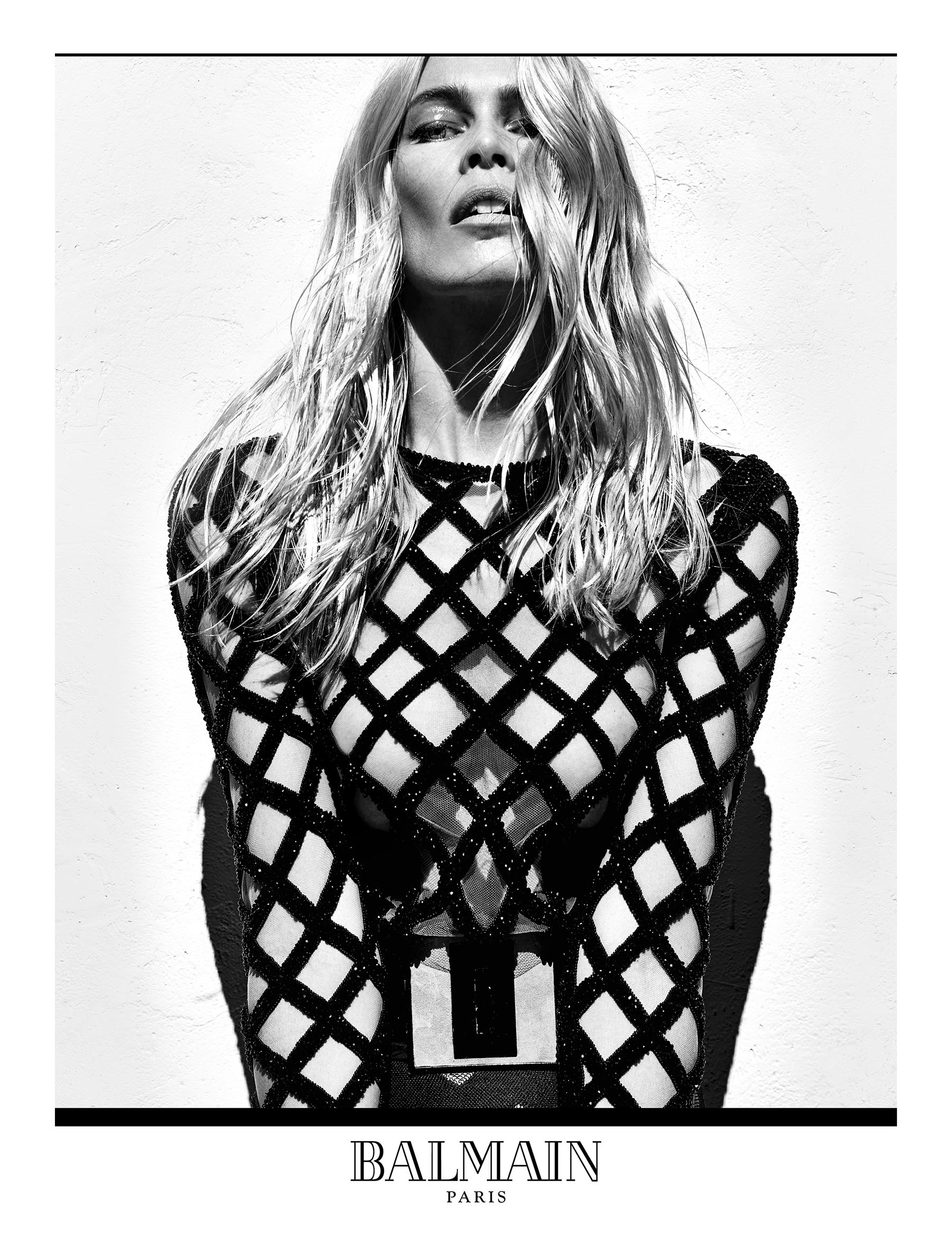

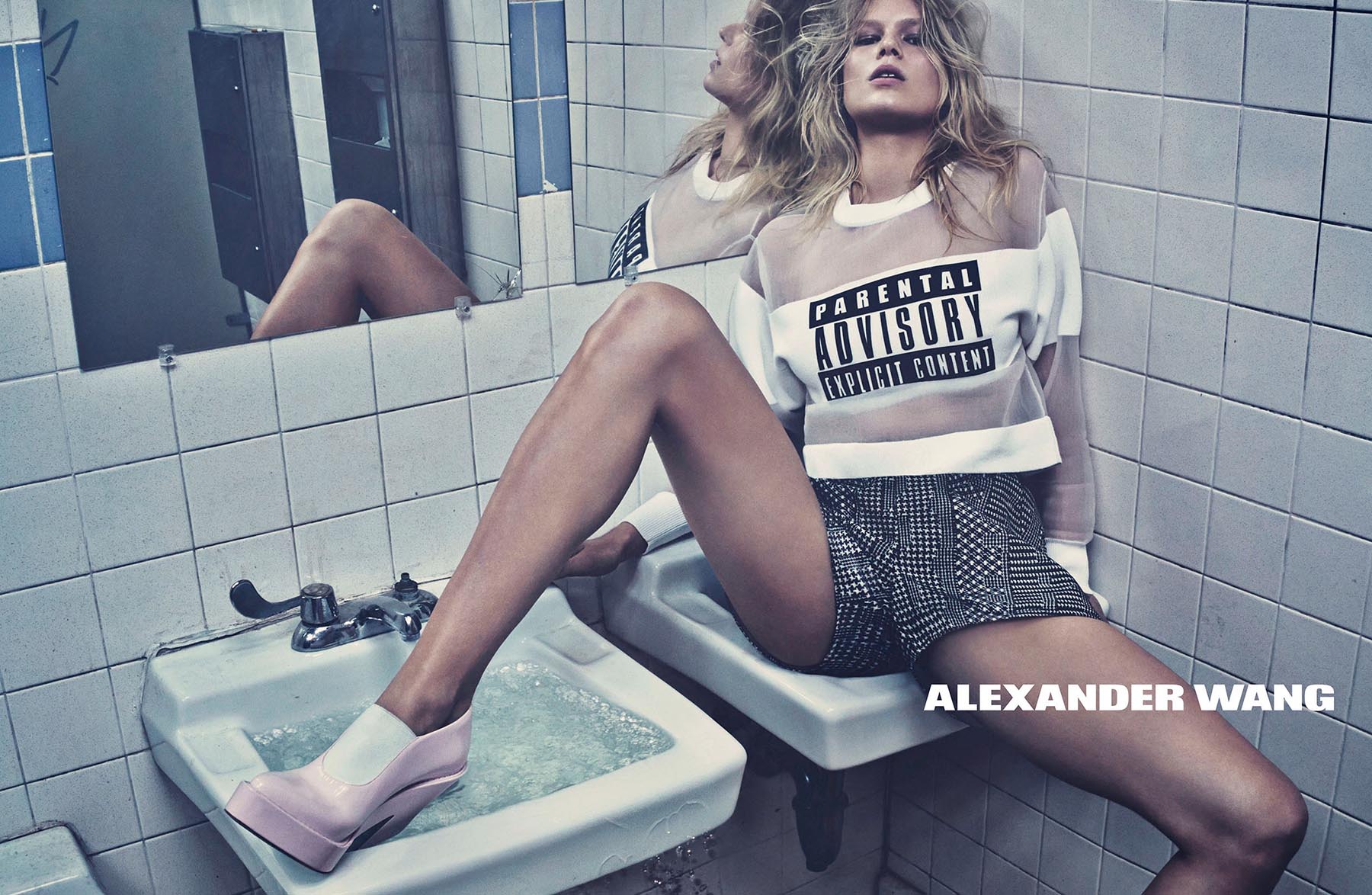

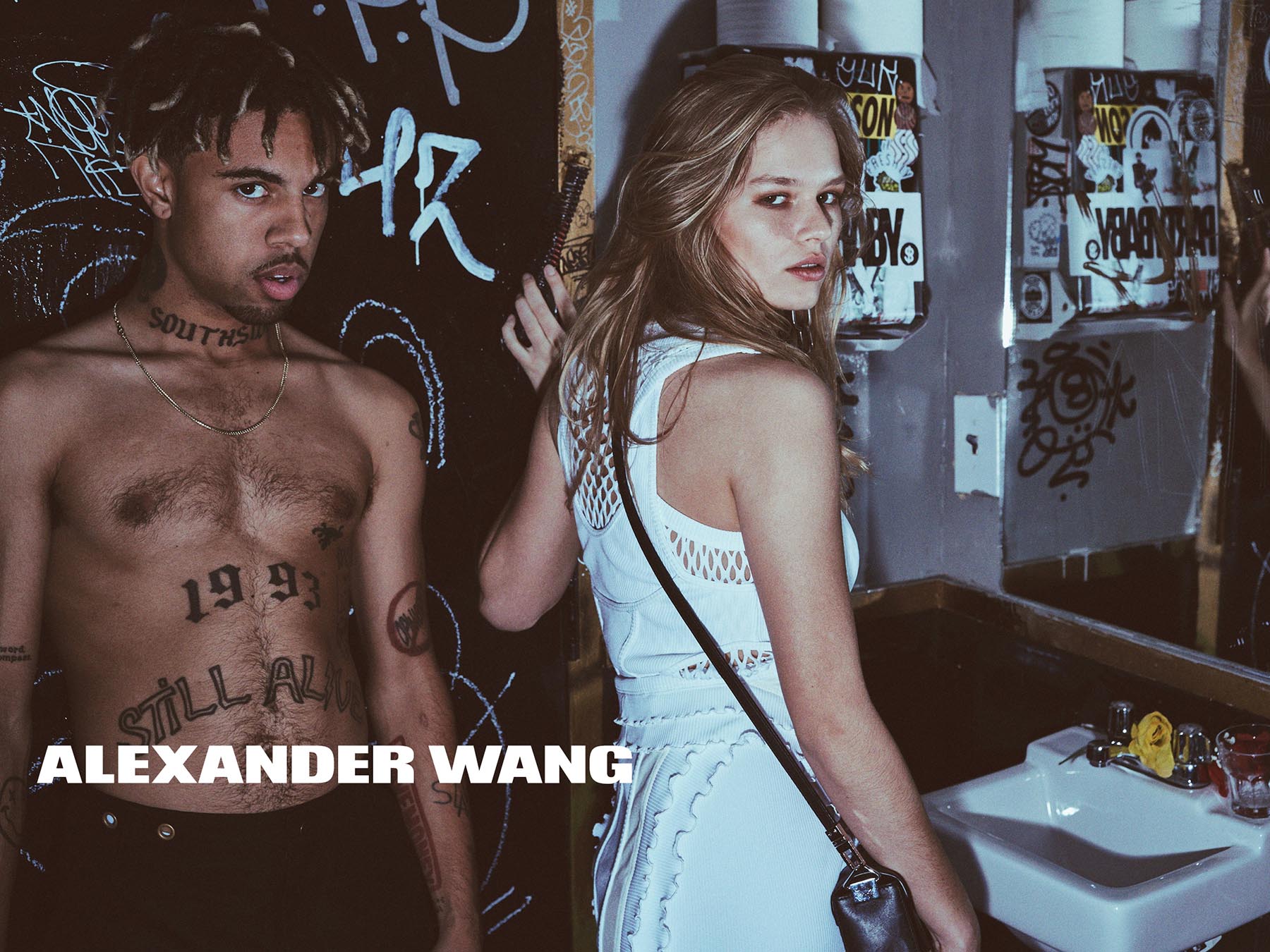

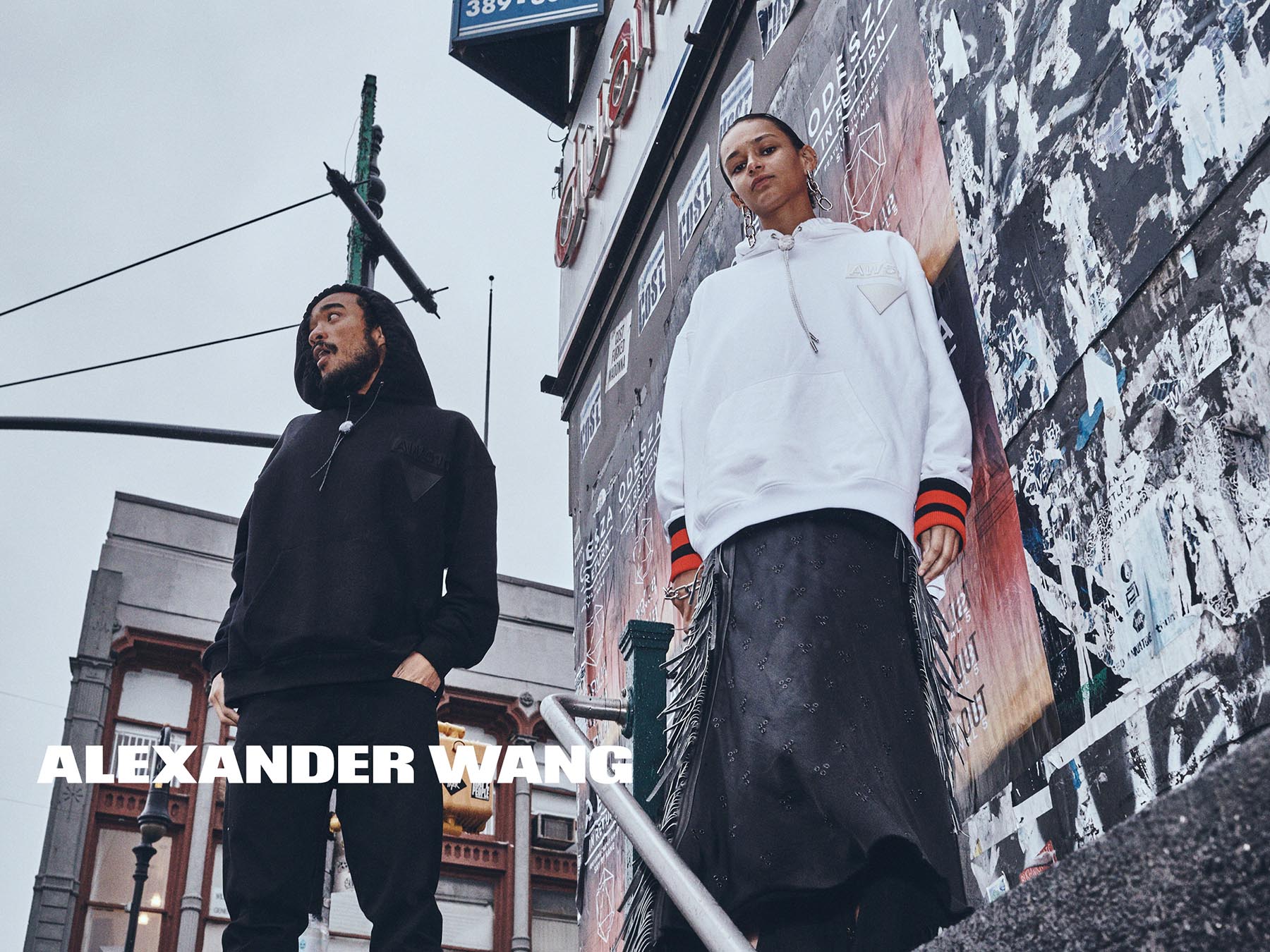

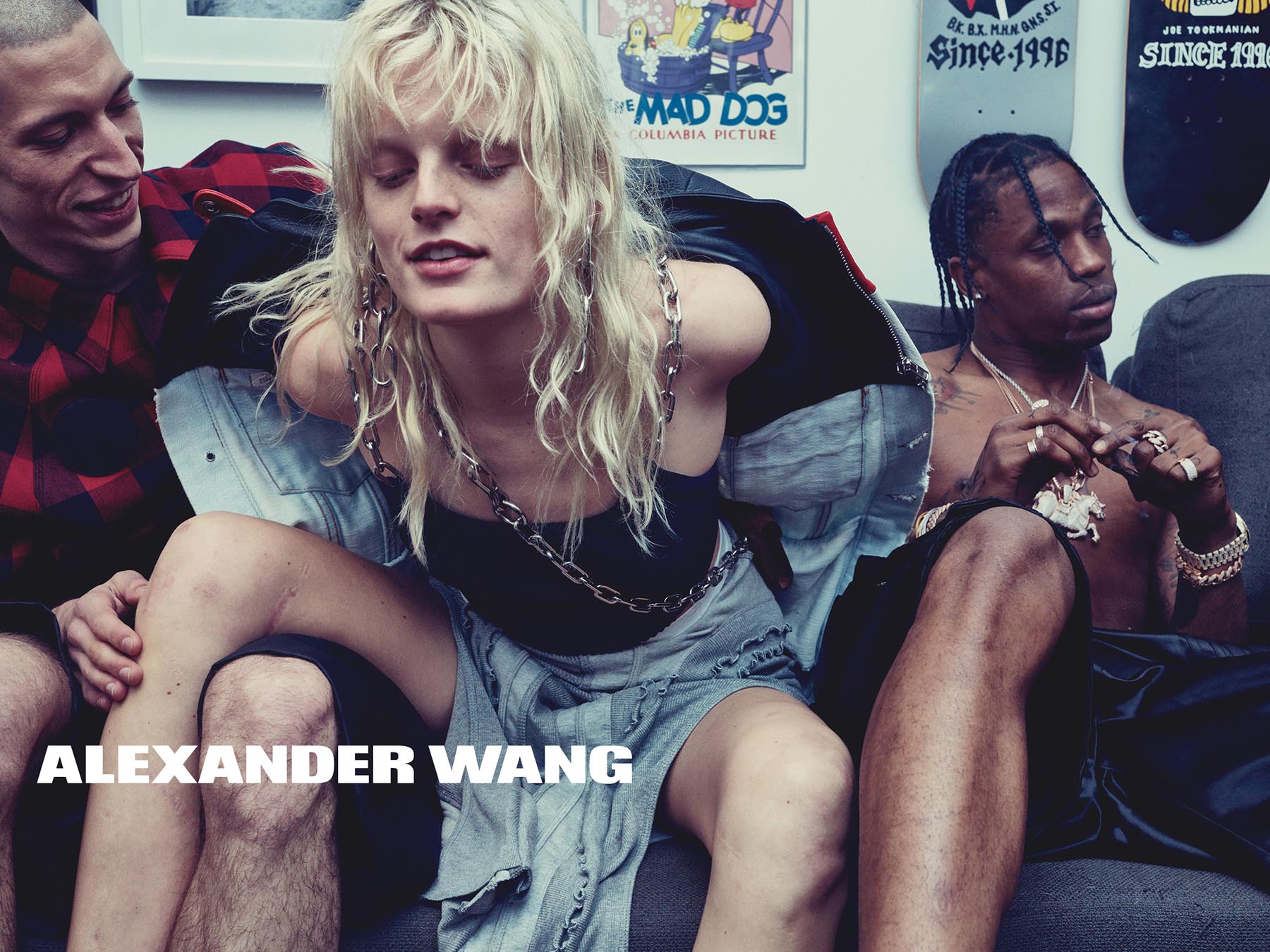

Alexander Wang was definitely a huge fan. Again, maybe he also wanted something different. I think I had something different to offer since I had a history of image making. I had that knowledge, that craftsmanship.

That craftsmanship, for me and many others, draws me into the images and I find myself spending more time with them. They are more thoughtful. How you are creating that experience?

Well, if you look at the work, really, they are simple pictures, there are no tricks or bells and whistles around them. It’s a girl, sitting, standing, running.

I think it’s the desire to think beforehand about what a client wants. When my collaboration happens with the designers that I work with, I want to understand everything about the person and I will have this octopus effect, embedding myself into their world and learning the same way I’ve learned everything else, by learning everything that they do. I spend more time listening to them than I do speaking. I don’t have an agenda, I’ve never known ahead of time what I want to say because if you have something to say, you never listen to what people are telling you, you’re just waiting for the opportunity to say what you have to say. So it’s always good to just really be in a state of calm and peace. The tricky part is to determine what it is that they want to achieve. We all know what we don’t like; it’s easy to define what one does not like. It’s much more difficult to define what you do like until you have seen it. But if I can at least define the parameters of what you don’t like, chances are, whatever I propose, you will like. Some sort of basic psychology is involved in this process.

And there’s a desire for modernity, the only thing that’s always there that’s very important, and I will always bring modernity, which simply just means that it’s today. It’s not what happened yesterday, and it’s probably not about the future. I think that the value, the equity that you build for a brand has to obviously be compounded and assembled.

Really, what matters today is how the world perceives a brand. How does the world react to your brand? No matter who the customer is, I believe they’re still going to appreciate beautiful things. According to that logic, then my kids will like the picture that I do, as much as you do.

It’s universal.

Yes, I see beauty as universal. Dostoyevsky always said, “Beauty will save the world,” and I really believe that. It’s important to learn to listen. It’s also important to have the eloquence to be able to explain what you want to do. Writing is so important, because you need to explain it on paper or aloud, what it is that you want to do. It’s just being able to have a raw reaction. But I never ever prepare what I’m about to say.

The here and the now. A lot of people think about the now and worry about whether they are ‘now’ enough, particularly with the technology that’s available. Do you have any thoughts about the ‘now’ as it relates to technology, or is it just another place to put images?

I think the media in terms of the ways we use pictures is almost non-relevant. It’s kind of our society today; this is how we look at it. So you adapt or die.

I mean, I love printed material, I love printed paper, but maybe we don’t want to kill so many trees, alright, fine. But you know a few people will still like books so, okay, I’m going to make books. It’s whatever is appropriate for the company. I think CMOs in businesses have trend studies, on which they probably spent a lot of money. But the truth is, as technology emerges, you want to embrace it, you want to think about it, you want to make sure that it’s right for you. You also want to react to it, and if you react – if you’re preemptive about it – then you will be the ahead of the curve. If you’re not, then you can adjust to always being a follower. But if you’re a follower, you’re not the leader; and if you’re not the leader, people tend not to pay attention to you. I think now there’s a genuine quality and a genuine story that needs to be told, and people are sensitive to that.

Regarding your own future, what are you currently looking forward to doing more of?

[laughs]

It’s the ‘more,’ right? You keep doing more, but more is probably not exactly what you’re looking forward to.

No, ‘more’ is not the word. I always have to love it.

I have a couple of heroes in my life. One is Thomas Jefferson. I think that his life was amazing in his ideas and his achievements, from writing the constitution to inventing ciphers and creating wines. He was an architect, gardener and writer. A renaissance quality is very important. I’m also fascinated with people like Karl Lagerfeld, who is so modern. I’m fascinated by his ability to do what he does all the time. It’s not about yesterday, and it’s not about tomorrow, it’s about the now for him.

Both are multi-faceted. Karl takes to the lens, too, but as a photographer. Have you ever picked up the camera to do some of the original camera work?

I’ve done a few things. But I think my love for photography has always been like the separation of church and state. However, there are times when I have very specific idea in my head and I can’t find somebody to do it, so I do it myself. And sometimes a client wants me to do that as well. Directing is more about that. I find directing film more needy because I have to lay out all the preparation for the film. I like syncing the film beforehand and building the film beforehand, and then executing.

We engage with many creators, and something that has come up repeatedly is the preparation before the shoot as well as the dynamics during the shoot.

My job is to make sure that what was intended actually happens, while still having the flexibility and the fluidity to say, “Hey, what about this?” Taking pictures is not problem solving. You do that beforehand.

What about family? Far too often I think that the perception is that family is something that doesn’t happen for all of us.

Family is a difficult subject, because family is something that I never really understood within the circumstance of my childhood. Now I have my own family. My wife and children make enormous sacrifices for me to do what I do. I don’t call myself a workaholic at all. I’m just passionate about what I do.

Do they get to share in that passion and experience?

Not enough. I wish I could. I think my first daughter, who is about to turn 20, can a bit more. She comes here and we often talk about what it means to build a business, to run your own operation. She is clearly proud. I love all three of my children equally, but I react to them differently because I am maybe more mature.

I wish I could have them with me so that they could see, but I much prefer them to be on the beach, looking at nature, and understanding how bees fly. I want that for them.

How do you describe to them, or other people, what you do?

[Laughs] I get that on the plane every other week. It’s like, “Are you a musician?” I’m usually a musician, a soccer player, or some sort of artist. Sometimes I get, “Are you a photographer?” but that would be because they see me with a print ad. I think I have to say I make images. I don’t really have a title, per se. I just love to make images. I called the company KiDS, because I simply just feel like I am a kid. I’m still this kid that just wants to learn all the time, every day.

Do you find yourself passionate about other curious people?

Do you find yourself passionate about other curious people?

I am interested in anyone who is a creator.

I was doing a movie with Madonna. It was really late, perhaps 3 am. Everyone in the room was exhausted. Madonna was next to me and she started singing because she was bored. She has this absolutely beautiful voice, and somehow, the magic of her voice, and the magic of her mind, that she’s able to sing something entirely new, a new rhythm, a new melody, really touched me. I can’t do that. I can do anything else in pictures, but I cannot do that, and I’m in awe of that. And to her, it’s like, “Oh, yeah yeah.” Because when we think of it as our normality, we don’t look at it as being extraordinary, and it is very difficult to have an objective appreciation of it. One thing that looks normal to you may look extraordinary to me.

I can only say that your work looks extraordinary to me. So grateful for sharing your journey and the ‘now’ with us.

You are welcome. Delighted to be of help.

Images Courtesy of KiDS Studio