The Comeback of Fur in 2023. More than two decades after the initial anti-fur campaigns, fur is back in the spotlight. Considering the implications, The Impression asks whether this will be a moral dilemma.

By Lizzy Bowring

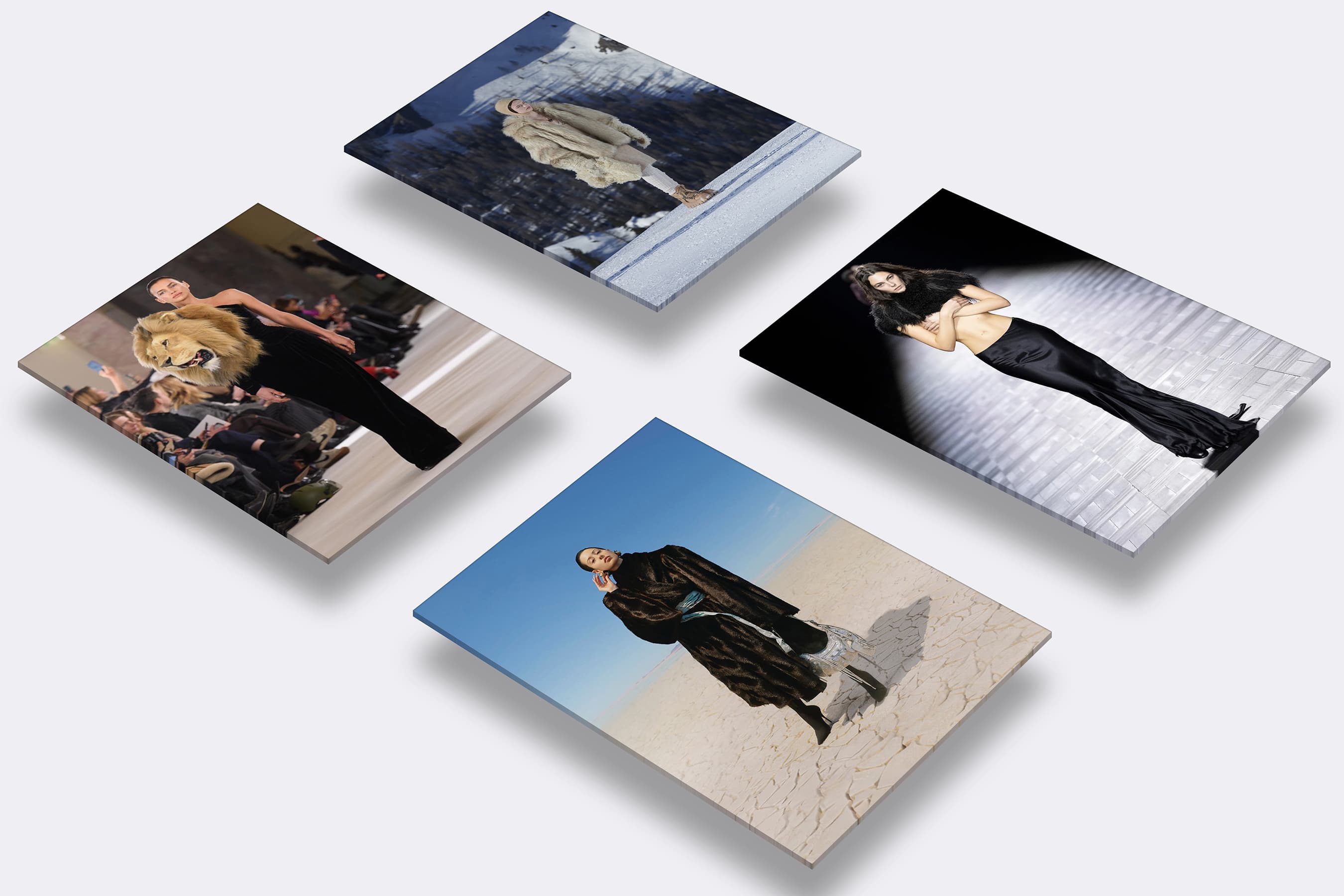

Fashion month, A/W 23, has shifted back to creating beautiful wardrobe essentials with designers executing their vision with considered refinement. Iterations of styles conjured a sentimental appeal in the handmade and the femme fatale, almost couture approach. And within the apparent trends bubbling up through the month came a focused return to Faux fur. Collections were awash in soft, cuddly textures, with several fabulous pieces showcased in eyelash feathers, exaggerated fur effect yarns, high contrast colour and re-cycled threads. And with the swing back to the elegance and sheer boudoir looks, it’s no wonder why fur has become necessary for warmth and protection, perhaps in response to the ever-changing global weather patterns or to emphasize the significance of trans-seasonality within collections. And all this came riding on the tail end of the recent Fur-ore at the Haute Couture season caused by the use of animal heads at Schiaparelli – thankfully not of the actual kind, but raising some serious questions. Daniel Roseberry unwittingly unleashed Dante’s inferno on the neverending dilemma over animal rights aesthetics. And now, in A/W 23, we are seeing such a resurgence of fur that the question over the ethical use of faux or real becomes even more poignant.

Fur coats and or fur accessories have been a cultural icon and practical necessity for centuries, and not just because they provided warmth and comfort. As early as the 11th century, fur was also a symbol of wealth and societal standing. Medieval European aristocracy wore fur hats, cloaks, capes, and gloves made from fox, sable, and mink. In the 1300s, regulations were established regarding who could wear what kinds of furs and who had to abstain. Around the 1880s, fur farms sprang up across North America to meet the surging demand for opulent furs from the fashion industry. Early explorers risked life and limb to discover continents rich in fur-bearing animals.

After the First world war, with the advent of the Golden Era, the prevalence of luxurious furs increased the popularity of fur coats and fur items. Despite the recession, this period is remembered as the days of glamorous Hollywood stars – Bette Davis, Marlene Dietrich, Claudette Colbert – and was especially true in terms of the looks and aesthetics that appealed to women of the day.

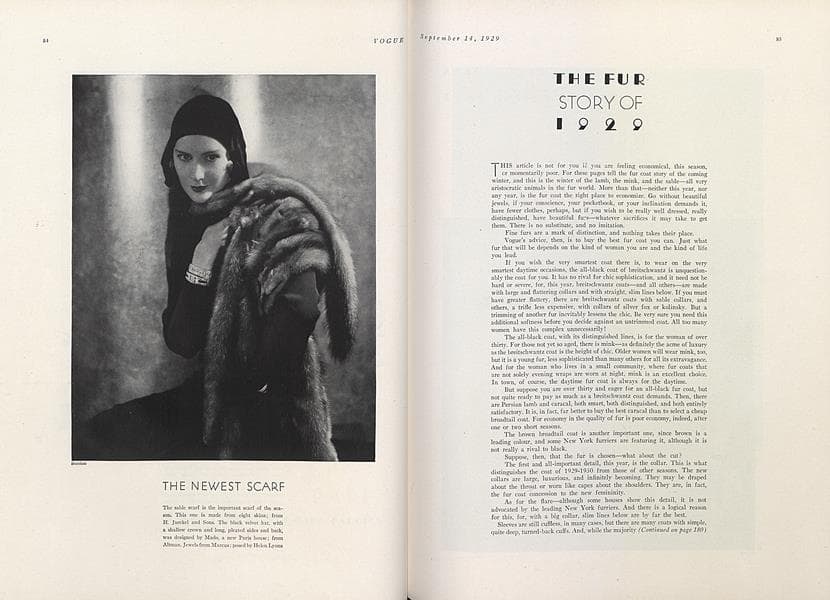

In 1929, Vogue featured “The Fur story of 1929.” The caption read: “Go without jewels, pocket money, or everyday clothes, Vogue advises, but never try to scrimp on fur. For the fur you wear will reveal to everyone the kind of woman you are and the kind of life you lead.” A fur coat and its owner were once an obvious sign of wealth and prestige, and this illustration captures that perfectly. (And fur wasn’t just for full-length coats, typically, the collar, wrists, and hem of women’s fur jackets often bore the trim).

As fashion became even more accessible through the 50s, the popularity of fur became increasingly prevalent in casual fashion. The length of fur jackets shrank, and styles altered to more abbreviated lengths, becoming increasingly acceptable for everyday wear. During their red carpet-performances, several of the most famous actresses of the 1940s and 1950s wore fur jackets over revealing cocktail dresses, adding to the style’s status and allure. Fur’s appeal, however, started to decline during the 1960s and 1970s. In the decade of the 80s, the value of a Fur acquisition increased, the tide changing with the advent of new money. Stars like Elizabeth Taylor were seen in fur pieces, and the frenzy that ensued is not dissimilar to the hype around today’s ‘earned media value.’ According to Business Insider, in 1977, fur retail sales in the US reportedly surpassed $600 million. A representative from the American Fur Industry informed the New York Times that by the late 1980s, retail sales had reached a record $1.9 billion. Fast forward to A/W 23, and the similarities of the rise in the popularity of fur to past decades are uncannily alike and more than likely one of the reasons why there is such a surge in popularity. The trend toward elegance and glamour from Hollywood’s Golden Age is returning, leading to the revival of fur jackets, or at least fur imitations. So what are the implications for consumers, brands, and sustainability?

The battle against the use of real fur. It’s what the consumers seek, while the new generation wants brands to take a hard line.

Since the early 1980s, the fur industry has been the subject of hostile animal rights campaigns, lest we need reminding of the stance made in the early 1990s as part of the fashion industry’s backlash against fur. People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) activists ambushed the Vogue and Calvin Klein offices, chained themselves to the sable coats at Saks Fifth Avenue, and demonstrated at London Fashion Week. The creation of PETA in 1980, along with its “I’d rather go naked than wear fur” campaign, fueled anti-fur sentiment with a further nail in the coffin of the industry, with farming banned in several countries.

Peta’s response to the Schiaparelli collection as “fabulously innovative” is somewhat about-face, as well as the media’s almost twin-tongued dissemination of the use of faux animals. The Instagram postings after Schiaparelli’s presentation spoke volumes: Carrie Johnson shared an image from the show to her Instagram said: “Grim! Real or fake, this just promotes trophy hunting. Yuck”. Misan Harriman said on his Instagram posting: “Dear fashion industry, this is NOT the way to start the year, nope NOPE NOPE!” and the postings continued. CEOs and creative directors are leading the anti-fur mission rather than angry protesters leading the charge this time. The discussion about animal rights, environmental viability, and whether or not the practice of wearing fur from animals bred for the purpose still fits in with today’s discerning consumer values is a moot point. Consumers seek it, while the new generation wants brands to take a hard line.

So how much of the fur we have seen on the runways is fake or real? That is a debatable question and one that relies on transparency from brands, particularly since there has been such a concerted effort by brands not to use real fur in their collections. “Young people today do not see real fur as a status symbol — they define luxury as innovation and sustainability.” Olivier Rousteing of Balmain states, “I decided not to use fur about a year and a half ago. I saw so many documentaries and thought I could not do this anymore. Now suppliers are working to ensure that faux fur can look like real fur, and it’s already pretty insane what they can create.”

The Implications of Faux. The perceived replacement of real fur by synthetics is a less-than-ideal substitute and questions disposability. Can Faux really be an alternative?

Faux fur has replaced traditional animal-based options in the fashion industry as consumers become more aware of the ethical treatment of animals. New advancements in technology and manufacturing have made imitation fur cheaper and easily accessible. But, and a big but, what if the synthetic fibers are made of acrylic and polyester? The sustainable question comes to mind because these are forms of plastic that are known to contribute to the microplastics found in the ocean.

And if a fake fur coat is thrown away, it can take hundreds of years to break down. Plastic production is set to triple by 2040, despite the vast evidence we now have of its impact on the planet and our health. Last week, research revealed that 171 trillion plastic particles are floating in our oceans.

– Emma Grace Bailey, Head of Content at PlasticFree

There are alternatives, but at this point, only the tip of the iceberg. However, on the positive side, manufacturer Ecopel developed a fur alternative with designer Stella McCartney that is 37% corn-based, with the rest made of synthetics or recycled polyesters. Koba, an alternative, has a lower carbon footprint and a more luxurious feel than existing faux fur alternatives. And building the success of this, Dupont and Ecopel are already working on new generations of Koba.

But material innovators show there is another way – without harming animals or the planet. Biofluff is a nascent stage material 100% plant-based without any chemical modification – meaning the faux fur alternative will decompose at the end of its life, much like a 100% undyed, unbleached cotton t-shirt would. The material is made from five currently undisclosed plant fibres sourced from agricultural waste, an additional benefit as the material doesn’t strain land that could be used for food crops.

– Emma Grace Bailey

Now, LVMH, one of the remaining luxury groups still using fur, is attempting to create a new, sustainable option using keratin, the main protein in hair, as the starting point. That LVMH is committed to developing new technologies is a heartening dialogue. Particularly since Fendi, a brand well-known for its use of fur is leading the fray. And in line with a commitment to sustainability, the number of fashion brands and retailers that have phased out fur or committed to doing so has climbed quickly, with recent pledges from Mytheresa, Oscar de la Renta, Burberry, Neiman Marcus, Coach, Miu Miu, and Canada Goose, among others. Kering, the parent of luxury brands including Gucci, Balenciaga, Saint Laurent, and Bottega Veneta, has announced that none of its fashion houses will use animal fur by this time next year. Luxury brands must continue to lead the charge, which is about being ethical, responsible, and eco-friendly.

Societal responsibility and creative problem-solving are the new hallmarks of affluence. With the season’s excesses, it is best to take stock of what has been laid before us and question.

But there is a caveat, brands need to be cautious. Bloomberg cites a comprehensive analysis published in January 2022 that the Polyester Filament Market will reach USD 174.7 billion by 2032. So in an effort toward sustainability, is there any way to ethically wear fur, faux or otherwise? It’s a hard fact to bear, but of the 100 billion garments produced yearly, 92 million tons end up in landfills. To put things in perspective, this means that the equivalent of a rubbish truck full of clothes ends up on landfill sites every second. Emma Grace Bailey, Head of Content at Plastic free, provides the most recent information on Faux Fur made from pure plastic, so while it’s ethically better, its impact on the planet is significant. It can’t be sidelined just because it’s solving another human-made problem. The same is happening in the vegan leather space; consumer demand for cruelty-free products has prompted a rebranding of synthetic alternatives through the lens of being better or the best when they’re just fossil fuels in disguise.

The argument is that a practical, considerate, and workable answer we can all take advantage of is genuinely appreciating what is already in circulation, including real second-hand fur that will biodegrade because it’s a more sustainable option than using raw materials to create new textiles. But more will be needed to satisfy the masses, and to this, we must examine the booming business of fast-fashion brands that peddle fakes to the masses under the guise of being animal-friendly. And this is the dilemma. Brands must be cautious about its multi-prevalence until there is a definitive answer to the bio-degradable ingredients of faux fur. However, one thing that can be done is to separate environmental problems from ethical and animal welfare considerations. That’s an easy fix; stop supporting brands that sell fur by not wearing it. Even if that line of thinking does not persuade the most diehard fashionistas, environmentally sound purchases can still be made considering an item’s longevity. So, choosing high-quality pieces that will last for some time and making moral choices about certified environmentally safe clothing is part of the answer. In other words, the only choice is down to societal responsibility and creative problem-solving, as these are the new hallmarks of affluence.

Perhaps we should take note of Schiaparelli’s creative director Daniel Roseberry. “There is no such thing as heaven without hell; there is no joy without sorrow; there is no ecstasy of creation without the torture of doubt,” And so, with the season’s excesses, it would do well to take stock of what has been laid before us and question.

The road of excess leads to the palace of wisdom…You never know what is enough until you know what is more than enough.

– William Blake