Review of Chloé, Courrèges, Dries Van Noten, Patou & Ujoh Fall 2021 Fashion Shows

The Day of New Beginnings and the Making of New Eras

By Long Nguyen

On this hump day at Paris fall show seasons, the day belongs to Chloé and Courrèges both with new creative directors at the helm – Gabriela Hearst and Nicolas Di Felice, respectively these two French houses into a new direction, ushering new eras for their brands.

As the first indication of change, Gabriela Hearst previewed her thoughts on the brand’s Instagram; in one short video, she spoke about the round and cocoon shapes at the house and how the shearling coat represents that silhouette.

In another teaser, Hearst mentioned the collaboration with Sheltersuit – an organization that makes full-length ‘house’ weatherproof outfits for the homeless. Hearst said she makes backpacks with Sheltersuit that, when sold, will result in the donation of in the forms of coats made entirely from repurposed materials. One of these coats was a parka made from a patchwork of print, stripes, and floral fabrics from past collections paired with a brown knit dress.

The idea is to commence the conversation on responsible production that has been Hearst’s fashion purpose into the core of the new Chloé.

In place of a live show, the taped show’s premiere started with models exiting the Brasserie Lipp, then crossing the boulevard Saint Germain, then on to rue Bonaparte heading towards the quai of the left bank. Gabriela Hearst chose the location in honor of Gabrielle Aghion, who started the brand using the name of a friend at the Café de Flore across the street in 1956 with a series of cotton dresses. Brasserie Lipp is where the founder staged a few of her impromptu shows in the 1960s.

On this exact day of the centennial of Gaby Aghion’s birth, Hearst sent the girls marching across the boulevard at night in a tribute to the spirit that gave birth to this French house that pioneered in bringing luxury to the mass. “There was no luxury ready to wear; well-made clothes with quality fabrics and fine detailing did not exist,” the founder Gaby Aghion once said of her clothes.

The models confidently cross the empty boulevard at night after the nightly curfew passing the Église de Saint Germain des Prés. They wore an army of clothes in lean and long shape knit, leather, and chiffon dresses in textured woolen striped ponchos giving the brand a new soft-spoken and subtle feminine vibes, and clothes made with a consciousness of environmental action at the forefront.

The clothes in this Hearst debut, showing mainly daywear, felt much softer and perhaps more approachable than those of her namesake collections that often seemed much more intellectual due to her deliberate thought processes in precision mathematics of the garment design.

The breeziness of the ecru dress in triple silk – pleated georgette, panels of satin, and hammered silk gauze – presented this new mood of fluid movement that rendered the clothes less of an intellectual endeavor. Here the textured of the cashmere ponchos that opened the show in brown or rusty country stripes is a descendant of both the heritage and the signature poncho in many of Hearst collections. The new poncho comes as a puffer coat.

Here and there, a few of the house heritage remains intact – the scalloped detailing featured on cotton piqué dress in 1960 now emerges as the topstitching of ecru georgette blouses and light camel knit dresses. This scallop pattern also appears on a colorful patchwork leather blouson and matching long skirt.

Immediately, the environmental impact of this fall collection will be at least more sustainable than the previous collections, with planning to accelerate further reductions by the year 2025. The new production methodology means complete elimination of virgin synthetic fiber (polyester) and artificial cellulosic fiber (viscose) and the sourcing of recycled, reused, and organic denim in the ready-to-wear category.

Besides, more than half of the silk used will come from organic agriculture, and over eighty percent of cashmere wool yarns for knitwear are coming from recycled sources. In accessories, the reduction of waste prompts a single version of the hardware applicable to all leather goods.

Linings for handbags will be in natural linen. The original Edith bag is now offered in recycled cashmere or recycled jacquard, even as a mini version in a tote or doctor’s bag. A limited-edition of fifty vintage Edith bags will be repurposed with leftover materials from this collection and sold as unique bags.

Hearst’s approach to her work at Chloé is laudable as the designer absorbed the fashion house’s idea but didn’t get mired in rehashing heritage fashion. From this strong debut she set forth the thinking for a new era at Chloé, Hearst isn’t looking back, but looking at Chloé now and asking what is relevant for young women today.

It is not about any collaboration with any artists to add caché to the collection. It is about how to instill these new values now inherent in the making of these fashion clothes, handbags, and footwear into the entirety of the Chloé brand.

More importantly, it is about corresponding these social and environmental values espoused by the Chloé house under Hearst with the same values now embrace by young women worldwide.

In another new beginning but one with an entirely different aura, Nicola Di Felice staged a live stream show at La Station – Gare des Mines, a party and underground dance spot in Aubervilliers north suburb Paris, perhaps in a nod to the anti-establishment house roots in the 1960s. The designer came of age in Belgium clubs when dance and new beat merged in these far-flung places that the youths gathered to commune with the new sounds.

Appointed as artistic director at Courrèges in November 2020, the Belgian Nicola Di Felice, a graduate of the École nationale supérieure des arts visuels de La Cambre in Brussels. He has worked under Nicolas Ghesquière right after his graduation in 2008 at Balenciaga for five years, then under Raf Simons at Dior, and in 2015 he returned to Louis Vuitton as senior women’s wear designer.

Founded in 1961 by André and Coqueline Courrèges, this small French house now under the full ownership of Artémis since 2018, the François Pinault holding company, is known for its experimentation with shapes with its A-line white dress and in using new technological fabrics at times like vinyl.

The collection Di Felice showed stayed close to the known signature looks of the fashion house. In an all-white painted space, models walked wearing A-line dresses within a collage of stretch jersey top, and wool crepe skirt with iconic front pockets and round seams, short windowpane coats, and long sleeve stretched mock turtleneck with a short black dress and matching flare pants.

These new Courrèges clothes look more familiar than new.

Di Felice’s main focus here seems first in remaking new clothes with the Courrèges emblems as a point of departure. The opening look of a significant volume long coat made from a reproduction of the 1963 check pattern follows those A-line dresses in white, bright red, light mauve, and black in jersey and wool crepe fabric.

Elsewhere, a black collarless pocket coat with black flare pants in bonded jersey fabric or the light camel wool circular sleeve mock neck jumpsuit is among the many wearable garments shown here. But the black midriff cut-out strappy short dress or one in black leather with small circular holes at the chest seemed out of place even though the cut-out motifs came from a 1969 collection.

In a house with a very recognizable signature heritage look, like the A-line micro sleeveless dress or those 1960s flare pants and mini skirt shapes, how much should Di Felice pay homage to these once iconic ways of dressing for many young women?

It is a central question that the designer has to ask as he moves forward in near future seasons.

Perhaps after paying homage to the past in this collection, Di Felice should design the kind of fashion he thinks is right for young women today regardless of whether the clothes ‘look’ Courrèges or not.

Heritage should not interfere with Di Felice’s work ahead. Otherwise, this new beginning will face difficulties ahead. It is like a quarterback throwing an interception at the crucial end zone after the two-minute warning signal.

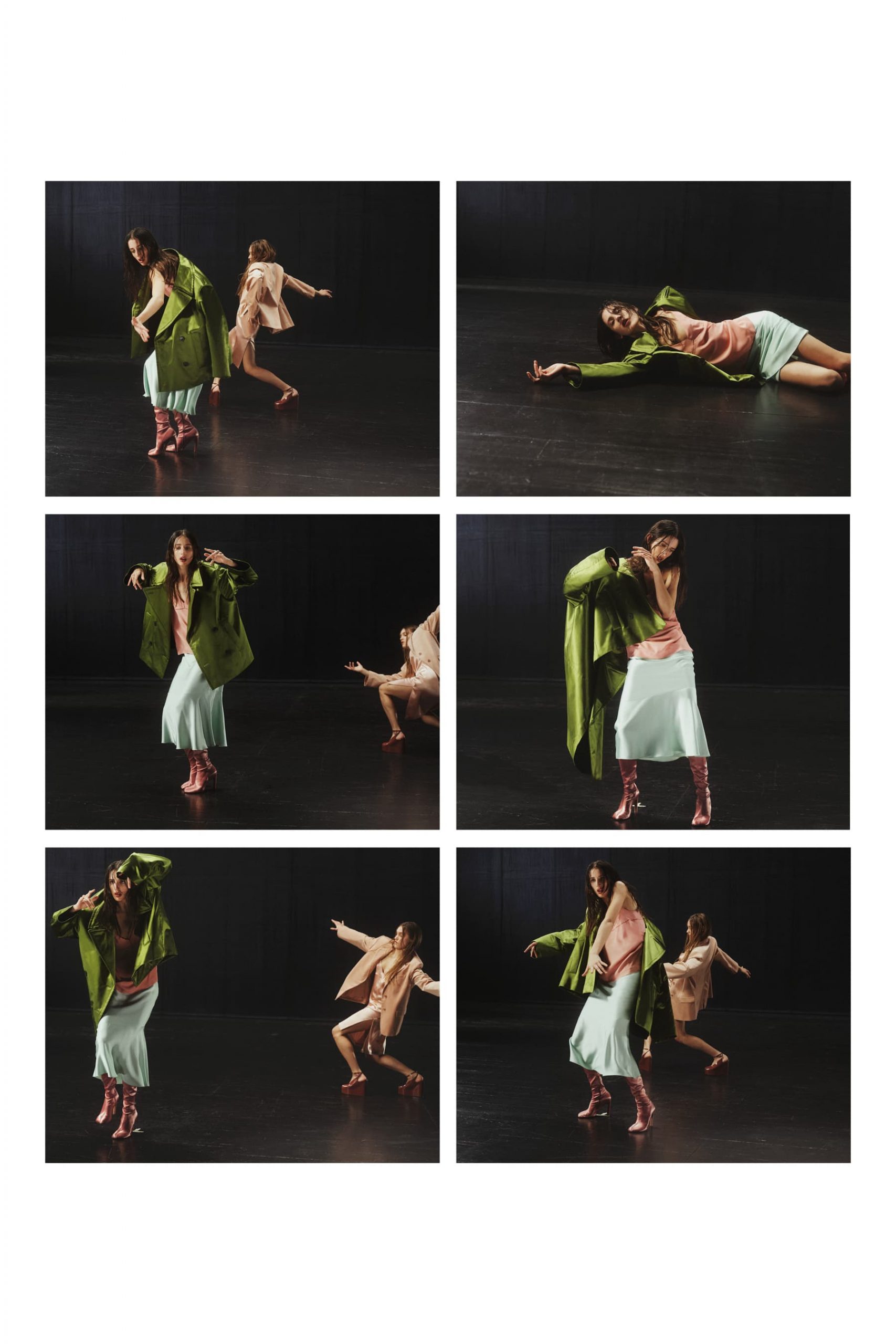

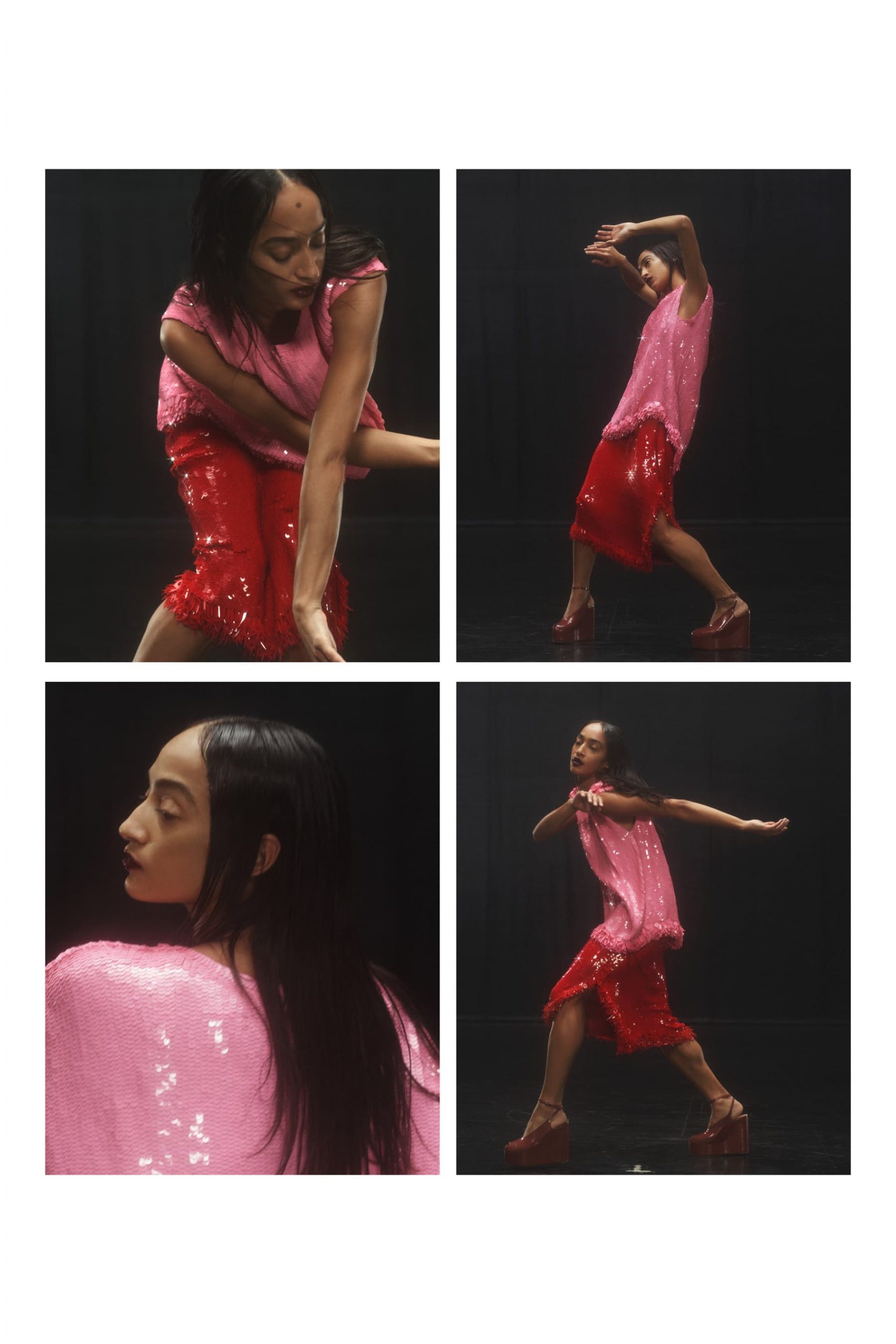

“This season, I wanted to make some more intimate, more personal with lots of emotions. A collection with an emphasis on movements and emotions,” Dries Van Noten said in a video message from his headquarter in Antwerp. “For emotions, we look to the world of Pedro Almodovar – love and passions – he used so much in his films. For movements, we look to the world of Pina Bausch – movement and emotion in perfect symbiosis.”

Van Noten presented a short film directed by Casper Sejersen. The film has a diverse cast of models and dancers from different dance companies in Belgium, including Rosas, Ultima Vex, and a few from the Opéra national de Paris. Choreographed by the Opera-Ballet Vlasnderen/Eastman director Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui, the fast-paced film saw models and dancers interchanging roles to demonstrate the contrasting aspects of the collection that meshed masculine and feminine in cuts, in silhouettes and cloths.

Structure comes mainly from elements of menswear. Fluidity comes from the more feminine side, the duchess and the satin. The menswear pieces in the collection are hiding the movements – you can hide your emotions in a big men’s coat. The more feminine thing is, of course, to expose.

– Dries Van Noten

The collection starts with a simple long-sleeve white cotton shirt ankle-length dress. A men’s navy blue wool single breast jacket follows. Then, onto a jacket with gold and red painted pattern in the front. The clothes evolve to combine elements of men’s and women’s garments. The mixtures often come from different fabrics to emphasize rigidity versus softness, for example, in an olive-brown cropped jacket and flowing pants in wool with a gold satin negligé camisole.

The agility of the contrast of movement and emotion and of fluid and structure forms the central tenet of the collection. Colors like red, black, or blue represent levels of emotions

Van Noten paired an oversize coat in grey satin with the red-painted motif with a red culotte and a camel bra top or a heavy grey wool double breast coat with a spread lapel with a short silver knit dress. Or even a straight camel trench coat over a red sparkling sequin dress and a white shirt with a red pattern and a men’s wool cigarette wool pants. The navy wool men’s coat with a large light green silk jacquard sleeve is another combination of one garment.

But a black sleeveless wool dress with a light pink satin sculptural fold insert at the front can stand on its own in this collection. This collection is the range of clothes that Van Noten has always delivered to his customers, only this time with a heightened sense of emotions.

“The clothes became something else when worn by dancers. It changes my vision of the human body and how the clothes are worn,” Van Noten said of the three days shoot that gathered dancers from across Belgium.

In a reality and documentary shoot at the studio for his fourth collection for the LVMH owned Patou, Guillaume Henri, the artistic director, can be heard directing the model behind the scene, at times dropping humorous lines his directorial role. “A profile shot with your face. Yeah, that’s beautiful. Magnifique,” the designer told Suzie, the model on set at the house’s studio.

Henri’s fall Patou collection is full of large and exaggerated volumes of clothes in the most bright color combinations. That means a yellow jacquard print floral A-line jacket with aqua blue lace lapel over a long slit front dress of the same fabric yellow marabou feather trims, a blue satin extra billowing short dress with ruffles, or a black taffeta silk dress with giant wing sleeves.

Henri makes even the most simple outfits like a cropped white jacket and hippie pants in a purple jacquard print worn with a sizeable white blouse. Or, for that matter, removing the added orange pleated skirt and long pants underneath would leave nice mauve wool cropped jacket skirt suit.

Henri’s fashion is not for the ordinary. It is the kind of fashion in a time warp that seems to have landed in the snow, but somehow with the exact date miscalculated.

That said, there should be consumers for this kind of fashion on the extreme opposite side of, say, a Rick Owens customer.

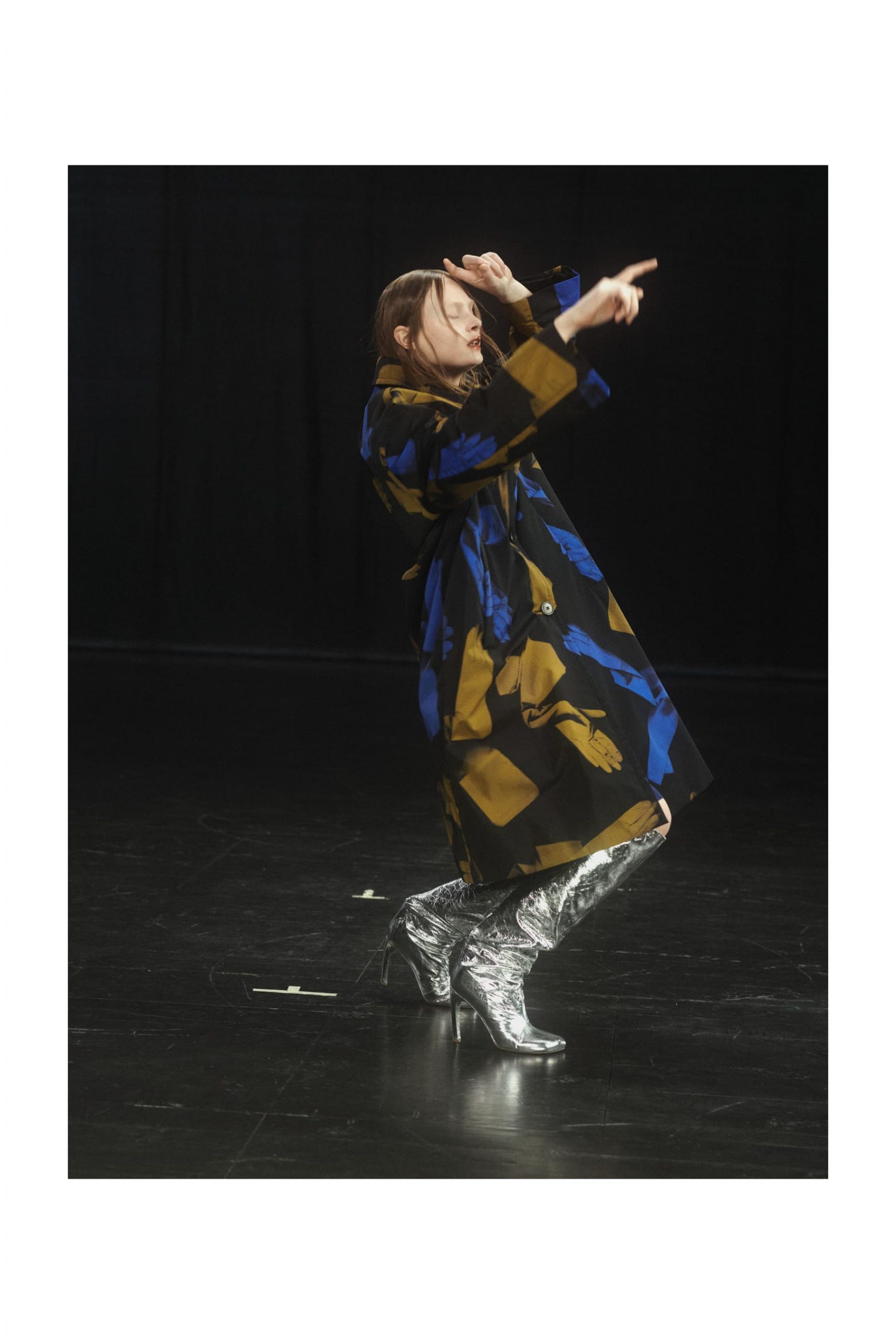

The Japanese designer Mitsuru Nishizaki established his label Ujoh in 2009 after spending more than seven years as a Yohji Yamamoto patternmaker. The designer staged his first show outside of Japan in Milano in 2016

That technical experience is apparent in his fall collection. Nishizaki layered lightweight tailored jackets and pants, soft blouses, and long tunic in monochromatic light grey and camel to create a sporty coed garment that is seasonless in a way.

The designer mixed masculine and feminine in his clothes with his clear understanding of how the different patterns can create a balance of layers for this season’s soft tailoring that looks weightless. The brushstroke prints contributed by the abstract painter Kanako Sasaki, now on a long dress or a wool camel coat with bright pink and blue brush motifs, enhance these streamlined clothes.

The black patch pocket belted short coat for women, and a blue plaid blouson lends a bit of sportiness to an otherwise meticulously constructed tailoring collection.

While the layering impact demonstrates the designer’s strength on the technical side of fashion, in future seasons, perhaps Nishizaki should think about fashion as an emotion instead of just another showcase of design ingenuity.

Nishizaki has to open up to new ways as to how his clothes can create these kinds of feelings.

Fashion is not always that logical balance between two patterns that may create a novel shape; fashion is also about the illogical imbalance of feelings and likes and dislikes.