Ahead of His MoMu Antwerp Exhibition, the Iconic Photographer Reflects on the Constant Artistic Practice of Nurturing a Youthful Perspective

By Mark Wittmer and Mackenzie Richard

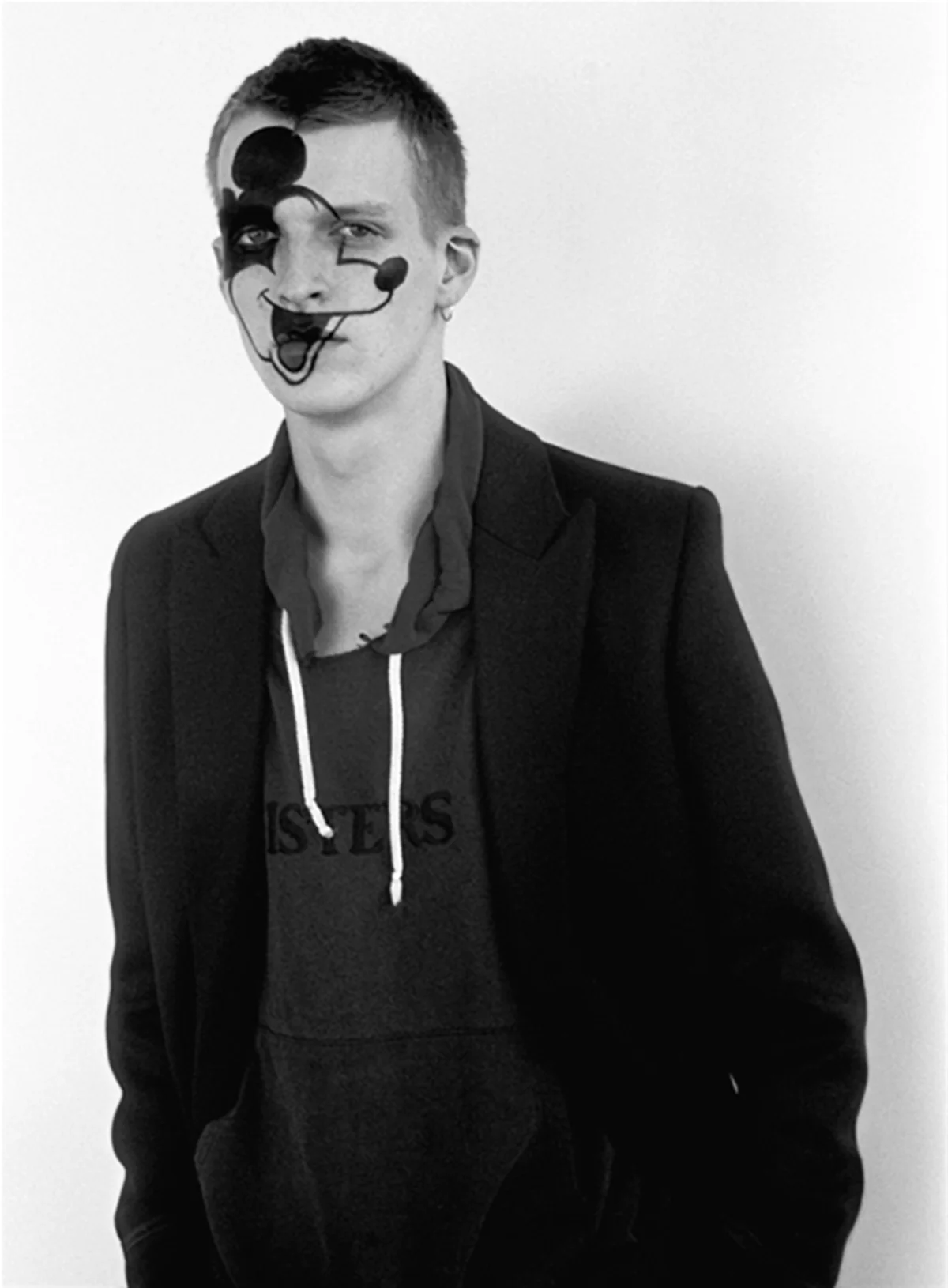

One of the most distinctive and prolific photographers working within the world of fashion (and beyond), Willy Vanderperre’s stark and striking work is characterized by a deep sensitivity toward youth culture and a constant practice of collaborative growth. Famously, his longest creative partnership has been with his husband, stylist and consultant Olivier Rizzo. The two met in their first year at Antwerp’s Royal Academy of Fine Arts, the launchpad of the famous “Antwerp Six” where they would soon forge friendships with Raf Simons and makeup artist Peter Philips – friends who are still each other-other’s go to collaborative team to this day, when each has formed their own influential and innovative path through fashion.

Now, the photographer’s work is being celebrated at Antwerp’s MoMu fashion museum in an exhibition that defies both the linear concept of an artistic career and the ostensible boundaries between fashion and art photography. On the eve of the exhibition’s opening, we caught up with Vanderperre to discuss his approach to collaboration, perspective on youth, the things that surprised him about revisiting old work, and thinking beyond the distinction between art and fashion.

Though Willy Vanderperre: prints, films, a rave, and more… functions in many ways as a look back at a vital photographic career, Vanderperre and the curatorial team have been intentionally avoiding the word retrospective. Instead, the photographer sees it as a more organic and open-ended window into a body of work that is far from complete.

“Retrospective kind of always puts you in chains because you have to follow a certain timeline and a linear thread that has to be coherent,” Vanderperre explains. “Whereas if you think about it as an overview, you can connect old versus new; you can invite people to walk through the exhibition and develop their own narrative based on the way they engage with the images and what connections they make between them.”

In a certain sense the exhibition does have a temporal starting point, as it only features work that has previously been published, and thus dates to the late 80s when a young Vanderperre’s work first began appearing in magazines. But the layout follows a more intuitive flow, and further expands beyond the rigid sequence suggested by a retrospective in its commitment to fostering conversation with other artists. Paintings ranging from Mike Kelley and Ashley Bickerton to Lucas Cranach the Elder and Flemish artists mingle with the photographs, while film screenings, nocturnal music events, and the titular rave will be held over the course of the exhibition.

A particularly personal example of this musical collaboration is with Belgian post-metal band Amenra, for whom Vanderperre previously co-directed a music video, and who will be performing an acoustic set to “immerse the show in their songs, providing another layer to the experience of looking.

“When I heard their album Mass IIII,” continues Vanderperre, “I instantly had to reach out to them because to me it was exactly the musical interpretation of the period and the area where I grew up. It completely transported me to a place that I didn’t really want to be, but at the same time also brought back so many memories, and some of them fond memories, around my hometown.”

That feeling of uneasy nostalgia is emblematic of a central theme throughout Vanderperre’s work: youth. The experience of youth, its distinct visual language and cultural power, and the ultimate transition out of it and lessons learned from it are all core concepts that shape the photographer’s visual vernacular. It’s a practice much broader and deeper than a mere celebration of being young, and the photographer’s carefully chosen words reflect this scope:

Nowadays I tend to use the word ‘youthfulness,’ because youth itself is so fleeting, it’s so transient.

– Willy Vanderperre

Nonetheless, Vanderperre points out, that ephemerality is one of its defining characteristics, lending further vividness to its tension between freedom and frustration, the discovery of oneself and the discovery that that self is at odds with the rest of the world. “Even if we don’t recognize it at the time,” he reflects, “we’re looking at things in a completely new way. So many new things are happening, both with our bodies and with the way we see the world. There are so many novelties that appear during that short period of time that leave us with wonder. And I think that’s the beauty of youth, that it’s a wondrous time. But it’s also a time where we are the most lonely. And I think it’s the time that we feel the least understood.

“Every period, every time creates a new form of youth, but the core feeling is that you feel misunderstood, that you think the world doesn’t really understand. And that you want to change the world that you have; you’re filled with ideas of the world you want and how to be in that world.”

One of the most exciting aspects of the exhibition’s fluid overview format is the opportunity to see how Vanderperre’s own youthful experiments and creative growth took shape and continued to inform his entire body of work. He reflects fondly, for example, on his early efforts at wrangling newly emerged digital photography, saying that its inability to capture shadow in the same way as analog made for a “challenge to rethink your light to get as close as you can to your analog. But then at one point, when you recognize that it’s a different medium you steer away from trying to mimic analog. So then you have to embrace the fact that you’re working on a digital platform with a digital camera and a digital technique.”

That ability to embrace challenges as inflection points toward developing a more distinct creative voice is an inspiring example of the way Vanderperre preserves that spirit of youthfulness in crafting his own visual meditations on the subject. “I will always cherish that period when technique was not so, you know, your forte,” he says, “and you just had to experiment and there was something beautiful about that world as well. I always try to keep trying to keep that alive in my work as well, to not just be satisfied with the techniques I understand, but to change it and bring something new to the image.

“It’s always pleasant to look back, but I use the word pleasant in a very positive but also in a negative way because pleasant is something that you feel comfortable with and it’s a nice place to hang around in, but you also have to get away from it because otherwise you just, you know, you get drawn to that affection.”

Collaboration has been another key element to this ever-evolving artistic practice. Along with his constant creative partnership with Rizzo – of whom Vanderperre says “it’s as much his show as it is my show” -, the team with which the photographer has been working for 13 years and more is central to the exhibition. And this is the case not only in terms of crafting the imagery, but in pushing the creative evolution and goals behind it. While one gets into a groove through working with a consistent group of like-minded collaborators, Vanderperre points out that “at the same time, it’s more difficult – because the more that you work with one another, the more that you have to challenge yourself even further. Once people say okay, we’ve done it, you have to improve yourself or try to change yourself or challenge yourself because the thing that keeps us awake and keeps me wanting to get out of bed every morning is to know that the challenge is there and that you want to take it on.”

Continuing that idea of artistic conversation and context that is central to the exhibition, the very concept of the overview itself is an example of the power of recontextualization, which brings up intriguing questions about the role of the photographer and the boundaries between fashion and art. Each of the photographs selected for the exhibition originally appeared in print, but now are hung on the white wall of a gallery space. Does this new curatorial context change something about the character of the image itself? For Willy Vanderperre, the answer is no – although it may bring to light certain perspectives on how we engage with image making in a world that is wholly determined by commerce and capital.

Speaking about his approach to photography in the ostensibly distinct categories of fashion campaigns and fine art, Vanderperre says, “I think it’s not a distinction. I hope to do with fashion photography the same thing I do with art photography. I still try to reflect on what is happening around us, to give it a little bit of a cultural content, to offer a vocal interpretation of what is going on in the world. In all of my work, I feel an urge to creatively push myself and tell my viewer how I feel about the world I’m living in now. So for me, there’s no difference.” Nonetheless, he acknowledges that not everyone sees it that way, recognizing that “some people hate the word fashion photographer because we, and fashion photography, are a little bit stigmatized. It can be very difficult for a fashion photographer to call himself an art photographer because we kind of give in to the commercial world.”

But he takes this idea even further, pointing out an inherently chameleonic duality within the practice of figurative photography. “The same picture, if it’s published in a magazine, it’s a fashion picture. If you put it on white wall, it’s an art picture.” So it is the context in which a viewer views an image that shapes the meaning and intent they ascribe to it.

Whether or not it’s accurate to consider a photograph hung on a white gallery wall as being more important than the same photograph printed in a glossy magazine or popping up in an Instagram feed, it’s undeniable that to experience an image in this way gives it a distinct impact. This is one of the reasons it’s so exciting and important to see Willy Vanderperre’s work – with much of which we may already consider ourselves familiar – celebrated both on its own terms and in conversation with the wider artistic community of which it is a part.

“My hope is that people who walk through the show remember at least one picture when they get home. And then I think I’m already successful with this show. I think life is so fast that we look at it and we just forget about it. I think if people walk through the show and there’s one image that touches them, in whichever sense – it might make them angry, it might make them sad, it might make them happy – but at least they feel something, then I will have done what I’m trying to do.”

Willy Vanderperre: prints, films, a rave, and more… opened at the MoMu in Antwerp on April 27th, and runs through August 4th.