Rethinking Investment Shopping and Luxury’s Response to the Vintage Phenomenon

By Mark Wittmer

The secondhand clothing industry is booming: according to the 2023 Resale Report from thredUP, secondhand saw strong growth in 2022 at 28%, while the global secondhand market is set to nearly double by 2027, reaching $350 Billion.

Nonetheless, it remains a question how the established fashion industry, and particularly luxury fashion, can respond to and capitalize on the booming resale industry, which in some ways can seem opposed to the goals of companies producing new luxury fashion. But a recent campaign from Vestiaire Collective offers new perspectives on how the fashion industry can harness shifting consumer attitudes toward fast fashion, luxury, resale, and conscious consumption.

Index

- Studies Show

- Girl Math

- Luxury and Resale: Rivals to Lovers?

- Key Takeaways

Studies Show

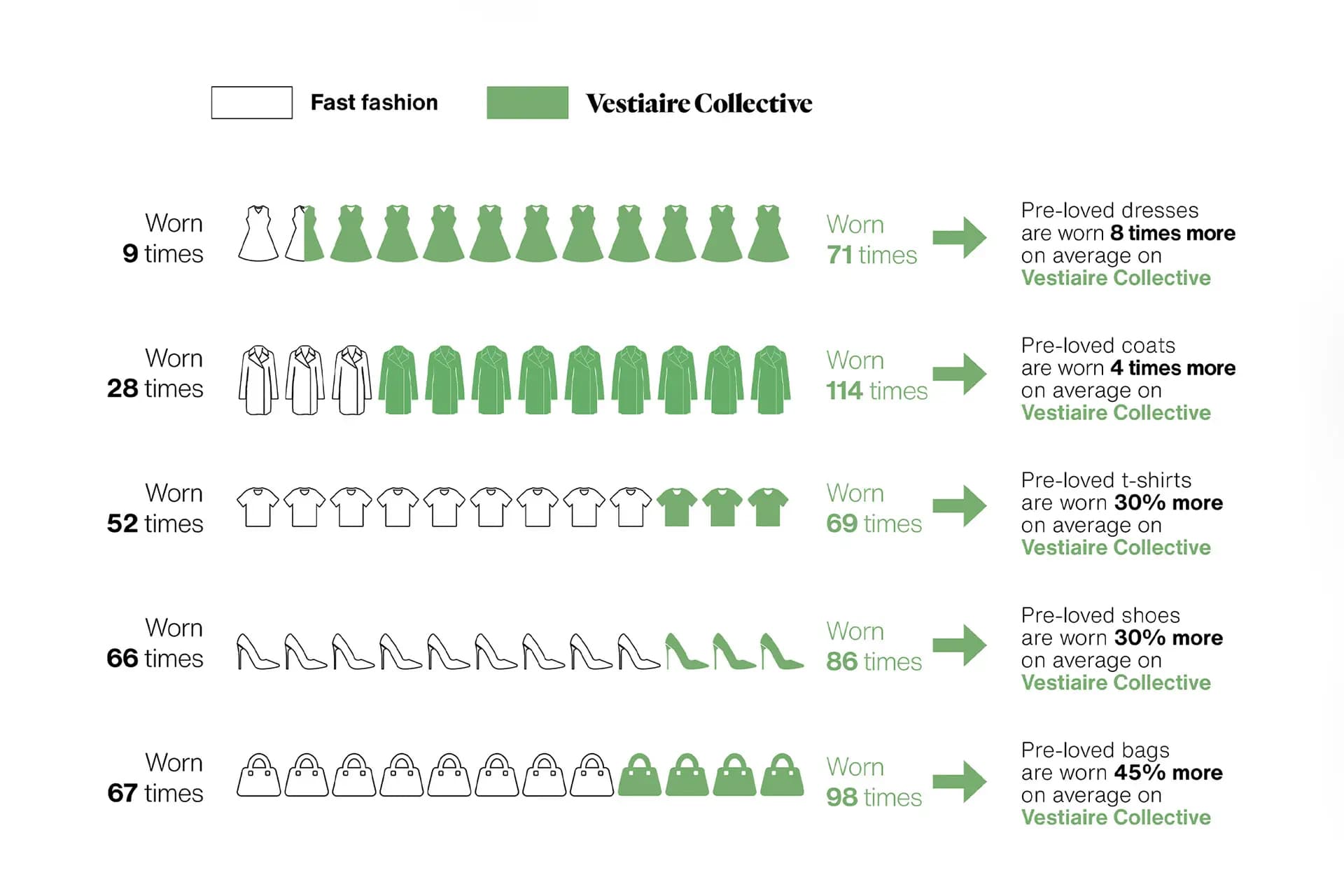

Timed to coincide with Earth Day and its buzz around sustainability practices, Vestiaire Collective’s most recent activation centered around a survey administered and published by the resale platform that highlighted the longevity of pre-loved fashion items and vintage consumer’s commitment to both investment pieces and conscious spending. The study showed that, when analyzed per wear, pre-loved clothes on Vestiaire Collective were 33% less expensive in the long run than buying brand-new fast fashion products. It also claimed that 60% of fast fashion items end up in landfill within a year of purchase, whereas on average, Vestiaire Collective users keep their items 31% longer – or 1.4 years more – than other consumers.

While there’s several reasons to take these findings with a grain of salt – it was done by Vestiaire Collective itself with responses from its own customers, both of whom of course tend to skew towards favoring resale over fast fashion – it does put a specific and relevant spin on an old adage that continues to ring true: it’s expensive to be cheap. While buying inexpensive things saves money in the short term, inexpensive things tend to last and be useable for a much shorter period of time, and ultimately you’ll have to buy the cheap thing many more times than a more expensive, better-made counterpart. If you have to buy the same article of fast fashion clothing every season, saving money will actually sooner or later become spending more money.

Girl Math

On TikTok, this economic phenomenon that it actually pays to spend more has found renewed scrutiny under the meme “girl math.” Poking fun at the supposedly feminine tendency to use sophistry and psuedo-calculation to justify purchases on categories that may seem ostensibly frivolous and girly – in particular fashion and beauty – the viral phenomenon spread like wildfire as creators jumped in to share their own applications of this new school of mathematics. The most common example is calculating an item’s cost per wear, which equals the price you paid divided by the number of times you’ve worn it.

As part of its activation around the study, Vestiaire Collective released a concise ad campaign applying girl math to a pair of today’s most coveted and on-trend style staples: a trench coat and loafers. While they don’t show their work, the math shows that a fast fashion trench coat (in this instance, from Zara) comes out at $4.82 per wear, while a pre-loved Burberry trench coat purchased on Vestiaire Collective nets a mere $0.98 per wear. Meanwhile, Zara loafers are at $3.38 per wear, while pre-loved Gucci loafers from Vestiaire Collective are $2.65 per wear.

The imagery is a striking and direct summation of the truth behind girl math, instantly illustrating that, while fast fashion may seem like a money-saving option in the moment, it’s actually almost always a worse investment (to say nothing of its environmental impact or labor practices).

Luxury and Resale: Rivals to Lovers?

The study and campaign invite broader questions on the relationship – or lack thereof – between luxury fashion and resale. While new luxury and vintage luxury resale seem to have opposed interests – buying pre-owned clothing potentially takes sales away from luxury brands, and vice versa – they share a common enemy in fast fashion. If it’s true that the enemy of my enemy is my friend, then independent resale platforms and luxury fashion brands may find themselves as unexpected amigos.

We have seen several intersections in the past as these two traditionally distinct entities experimented with crossovers and partnerships. Vestiaire Collective itself has partnered with Burberry, Courrèges, and Chloé on buyback programs that reward fashion lovers for trading in their archive pieces with gift cards to put towards new clothes at those brands. Meanwhile, Valentino, Gucci, and more launched in-house refurbished vintage programs.

Luxury resale is still in its nascent stages, and we’ll see new strategies begin to emerge and develop as time progresses. The main challenge tends to be that luxury houses don’t have the same buyback infrastructure that platforms built from the ground up with resale in mind do, nor the directness and accessibility of peer-to-peer resale sites.

For now, partnerships between brands and resale platforms – which present an avenue to which more and more fashion aficionados, and particularly young ones, are turning – offer a strong way to capitalize on this change in consumer spending. In addition to claiming a small portion of the resale profits, brands can also build awareness and covetability, increasing the chances that a vintage customer will become a direct customer in the future. These partnerships are mutually beneficial for the resale platform in that they further position them as an authority in the fashion industry and drive site traffic.

Key Takeaways

As the secondhand movement continues to gain momentum, questions arise about how the luxury fashion industry can navigate and capitalize on this burgeoning resale market, seemingly at odds with its primary goal of promoting new luxury items. Vestiaire Collective’s recent program sheds light on this dilemma, emphasizing shifting consumer attitudes towards fast fashion, luxury, and conscious consumption. The campaign underscores the economic principle that quality often outweighs quantity, challenging the notion that fast fashion is a cost-effective option in the long run. Through partnerships between luxury brands and resale platforms, both entities stand to benefit, capitalizing on changing consumer behaviors while fostering a sustainable and mutually beneficial relationship.