The Activism of Hope

Misan Harriman is the first black male photographer to shoot a cover for British Vogue in its 104-year history. This is at once both celebratory moment – but also shameful that it has taken so long. Now, through his own digital platform, Harriman has some important insights to share for the fashion industry…

If people are empowered, there are so many amazing writers, artists, curators, and editors from all walks of life that have this incredible viewpoint on how things can be better. But there are still a lot of very powerful people that are from a world where they’ve never had to think about race in the way that many have been forced to in the last six months. The question we all need to ask of that generation – who are still so influential in film, music, publishing, and advertising – is: what are they going to do? Because if they do something beyond tokenism, then the change will be extraordinary.

– Misan Harriman, Photographer & Founder of WhatWeSeee.com

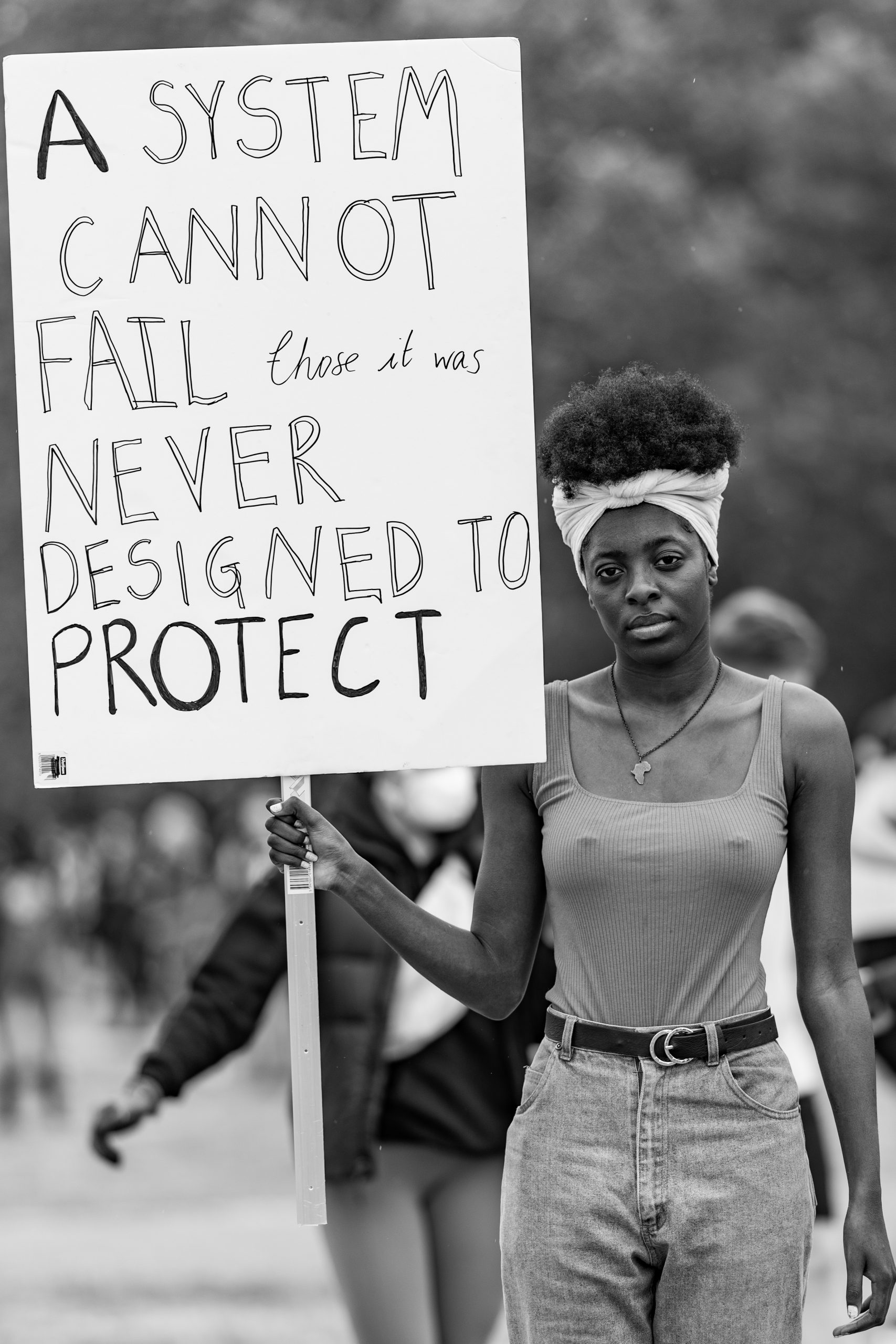

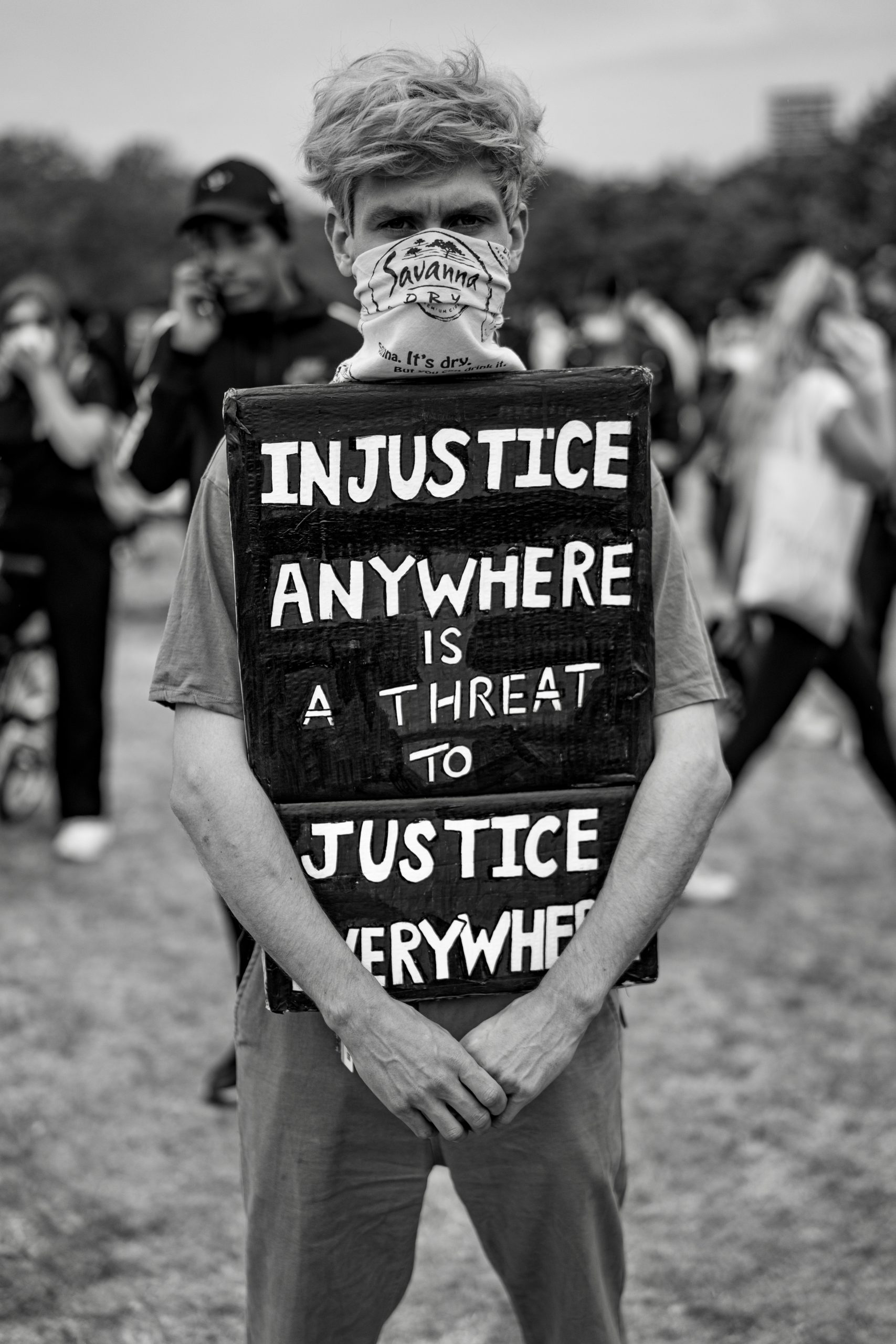

Harriman has been busy both documenting and facilitating extraordinary change himself. Most recently he has been one of the key chroniclers of the BLM protests, capturing powerful images in stark black and white while attending rallies in London.

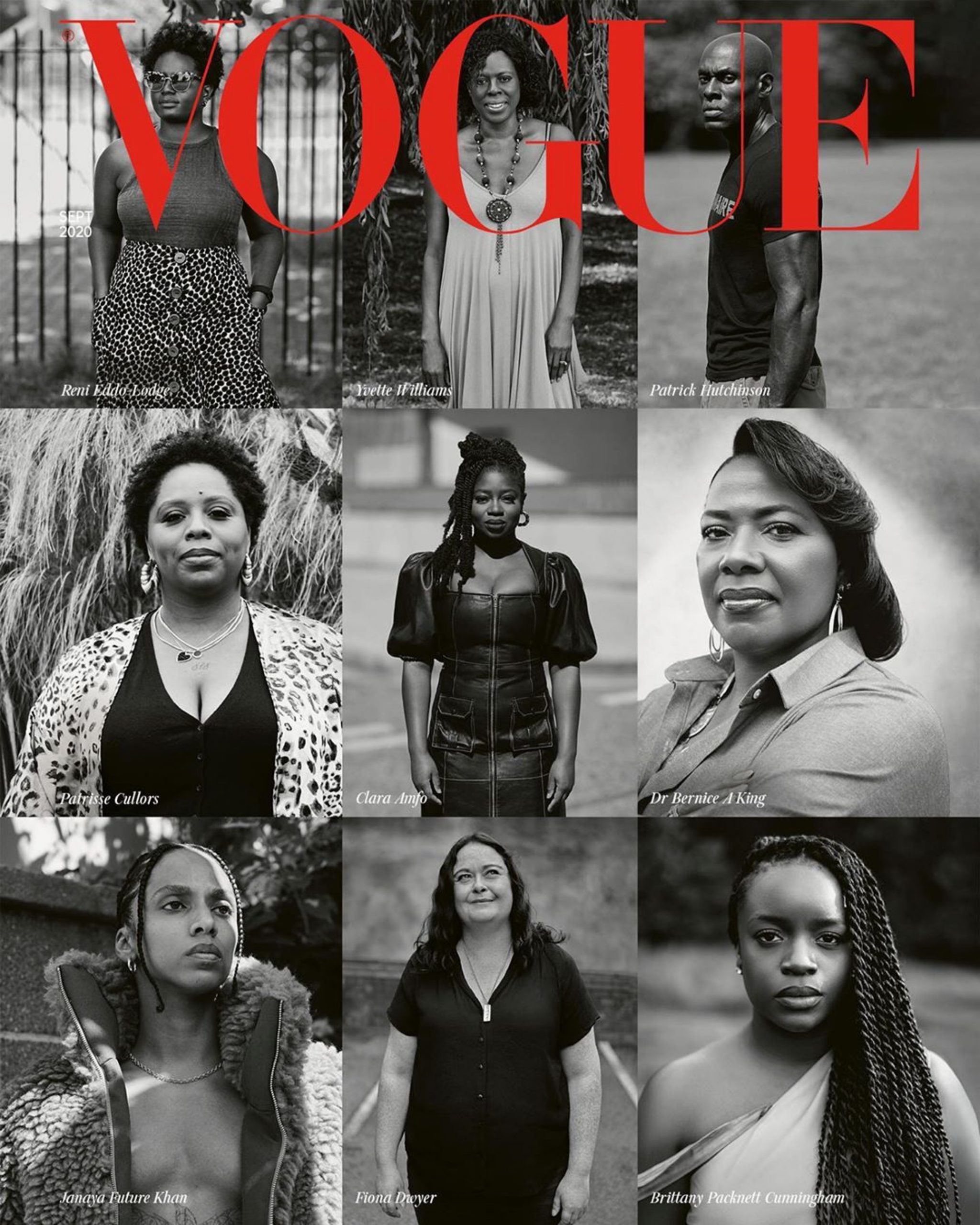

With his imagery ‘beginning to go everywhere online’, Harriman began to gain traction amongst his impressive A-list of social media followers, celebrities and influencers – not least Edward Enninful OBE, Editor-in-Chief of British Vogue, who shared some of Harriman’s images on his personal Instagram Stories. But this – and several online stories – was merely the prelude to a historic moment, when Enninful commissioned Harriman to take a number of portraits for the ‘Activism Now’ portfolio in the September issue, including the lead cover image of model, and mental health activist, Adwoa Aboah, and soccer player Marcus Rashford (included in the wake of his successful social media campaign shaming the UK government into reversing their policy on freezing free school meals during the lockdown).

This was the first time a black male photographer had shot a British Vogue cover in its 104-year history (following Nadine Ijewere, who became the first woman of color to shoot the cover of any Vogue for the January 2019 issue – again under Enninful’s watch). What is noticeable about the story is how both Enninful’s editor’s letter and the accompanying essay by Afua Hersch emphasizes a message of hope. ‘Edward has got to that level where he can see things from a birds-eye view,’ says Harriman. ‘That’s part of his genius. And he is hopeful. And that is something that has trickled down throughout the culture of British Vogue, and also with the people he chooses to work with. My images too are about hope, and solidarity, and education – and looking forward towards making our future brighter in regards to race relations.’

This dovetails neatly with the ideals of Harriman’s own brand, WWS – an online platform aimed at re-establishing social media’s role as a force for good, under the neat slogan ‘There are two ways to win the internet: one is with extremism, and the other is with empathy.’ Harriman expands on this further: ‘If you feel really something, it can make you weep as well as make you feel good. But the kind of tears that come from empathy are tears that will make you improve whatever made you cry. And that’s a very different part of your emotional engine. So I always say with WWS, I want you to do three things: I want you to learn, I want you to laugh, and I want you to cry. If I can meet all those parts of your emotional spectrum, then I feel we’re doing our job right as a media publisher.’

‘The origins of the business were to try to make a more safe, enriching, inspiring digital environment, in a world that was being more weaponized and unhealthy,’ explains Trevor Hardy, CEO of WWS. ‘And our weapon in that fight was always film, music, arts, culture, spoken word, rather than current affairs, and we pitched it commercially as a safe space for brands to tell their stories. The last number of months has helped us to focus that even further – not specifically around race or gender or equality – more about what the purpose of us curating and publishing all this stuff was. Whether that was through Covid, or BLM, or other issues.’

The pair describe WWS as ‘an empathy engine’. ‘Our mission is trying to transform the world’s digital diet,’ continues Hardy. ‘Because of what’s been happening culturally, societally, socially, I think the world needs a lot more empathy, understanding, patience, and perspective. And great writing, a great photograph or a great poem still has the power to help people understand one another.’

What is particularly interesting from Hardy’s experience is how their commercial conversations have become much more focused around ‘brands that are telling more purposeful, more sustainable, more ethical, more human-related stories around the work they’re doing or the products they’re selling, or how they operate. I think because commerce has tanked over the past few months, a lot of brands have focused on being more civically minded – being better businesses by being better corporate citizens.’

By way of example, Harriman cites P&G’s short video The Look to show how brands can help to reposition the lazily defined concept of ‘normal’ by raising the bar in terms of empathy.

Similarly, Unilever’s ‘Unstereotype Experiment’ campaign hits the nail on the head, proclaiming itself as ‘an opportunity to our marketeers to have a moment of self-discovery’. In the 4’30” short, business psychologist Dr. Gorkan Ahmetoglu states, ‘We’ve learned to use stereotypes in order to simplify our world.’ But, they point out, these stereotypes, amplified through campaigns, then shape our cultural perceptions, encouraging us to think of people in terms of specific groups rather than simply as human beings. Revealing the DNA ancestry of key Unilever marketers, they challenged their assumptions around race whilst emphasizing the commonality between colleagues with seemingly different ethnic identities – encouraging the idea that ‘…if you see yourself differently, you’ll be more willing to see other people differently’.

‘For the last number of years, there have been more platitudes around the idea that it’s just good business to be good,’ says Hardy. ‘But there hadn’t been much demonstrable proof around that. But now I think the opposite impact is much more motivating: it is actively bad not to be a good business. There is now consequence if you are not diverse or not ethical – not doing the right thing – whereas before you might get away with it.’

To put it simply, brands in 2020 need to think harder than ever about how they present themselves (‘culturally, societally, socially’) – and, as Harriman points out, they now have to adhere to a more responsible and inclusive modus operandi ‘whether they like it or not.’ While he is encouraged that this increasingly comes from ‘a genuine instance of looking inwards and an understanding of what they may have missed in the past’, he agrees with Hardy that, for others, there is still a more cynical motivation – that it is ‘the thing to do.’

But, as a simple exercise in how the fashion industry is repositioning itself, one only has to open the September issue of British Vogue and thumb through the ads – starting with a four-page gatefold from Ralph Lauren, followed pages from Gucci, Prada, Louis Vuitton, Kurt Geiger, Michael Kors, Valentino, Issey Miyake and more – all of which display a noticeably diverse use of models. Whether this becomes the new normal remains to be seen. The question remains why it has taken this long for brands – not to mention society at large – to make the change.

‘It’s not surprising to me,’ says Harriman. ‘If you don’t have that lived experience that many black men and women have had from the moment they step outside their door, how are you meant to be aware that the lens of life that I have to look through of life is very different than yours? It’s as simple as that. It’s not a criticism. But again it all goes back to empathy – if you don’t have empathy, you don’t care anyway! “I just want to get my mortgage, get my kids through school, have nice holidays – and that’s all my focus. Life is hard enough.” Right? So many people are like that. And that’s a problem.

The people that are going to make change are the people that understand that they have to sort themselves out but know that the future is not going to be a future worth working for if so many others don’t have the same opportunities that they have had. And that’s where we need to head towards.

– Misan Harriman