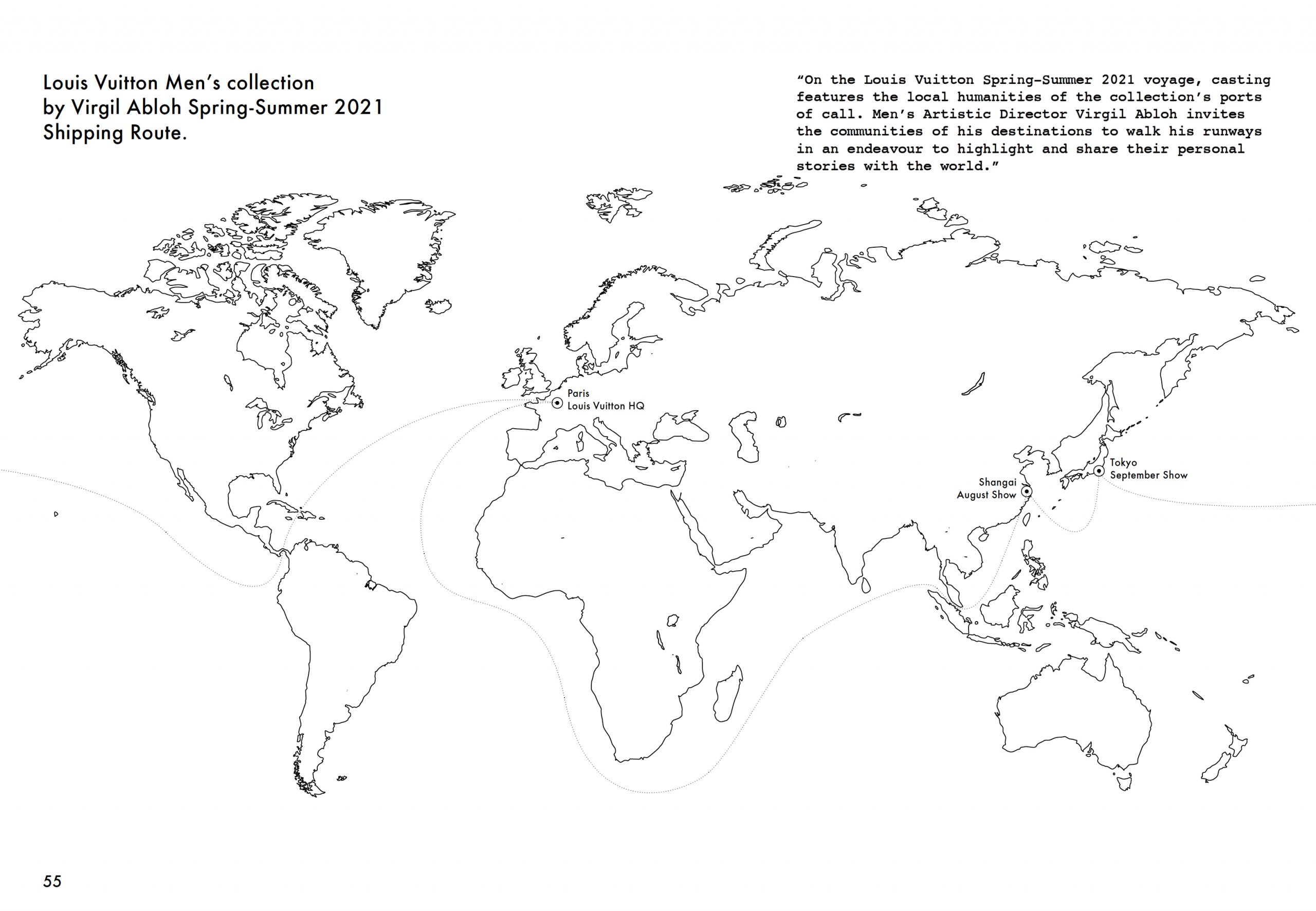

Virgil Abloh and Louis Vuitton have released the show notes for the Men’s Spring/Summer runway show in Tokyo on September 2nd. Going far beyond the breadth and scope of show notes’ traditional purpose, the document serves as a detailed and provocative blueprint for the ongoing artistic endeavors of the man who seems poised to define the decade and raises complicated questions about the role of the creator.

Typically fashion show notes are just that: details about looks and elements from the show which are meant to aid buyers and audience members. In the last couple of years some progressive designers, such as Gucci’s Alessandro Michele, have infused the notes with personal and artistic touches that holistically echo the themes of the collection and shows. But this new move from Abloh is massive and unprecedented, and may suggest a paradigm shift in the way we think about a designer’s relationship with their own work.

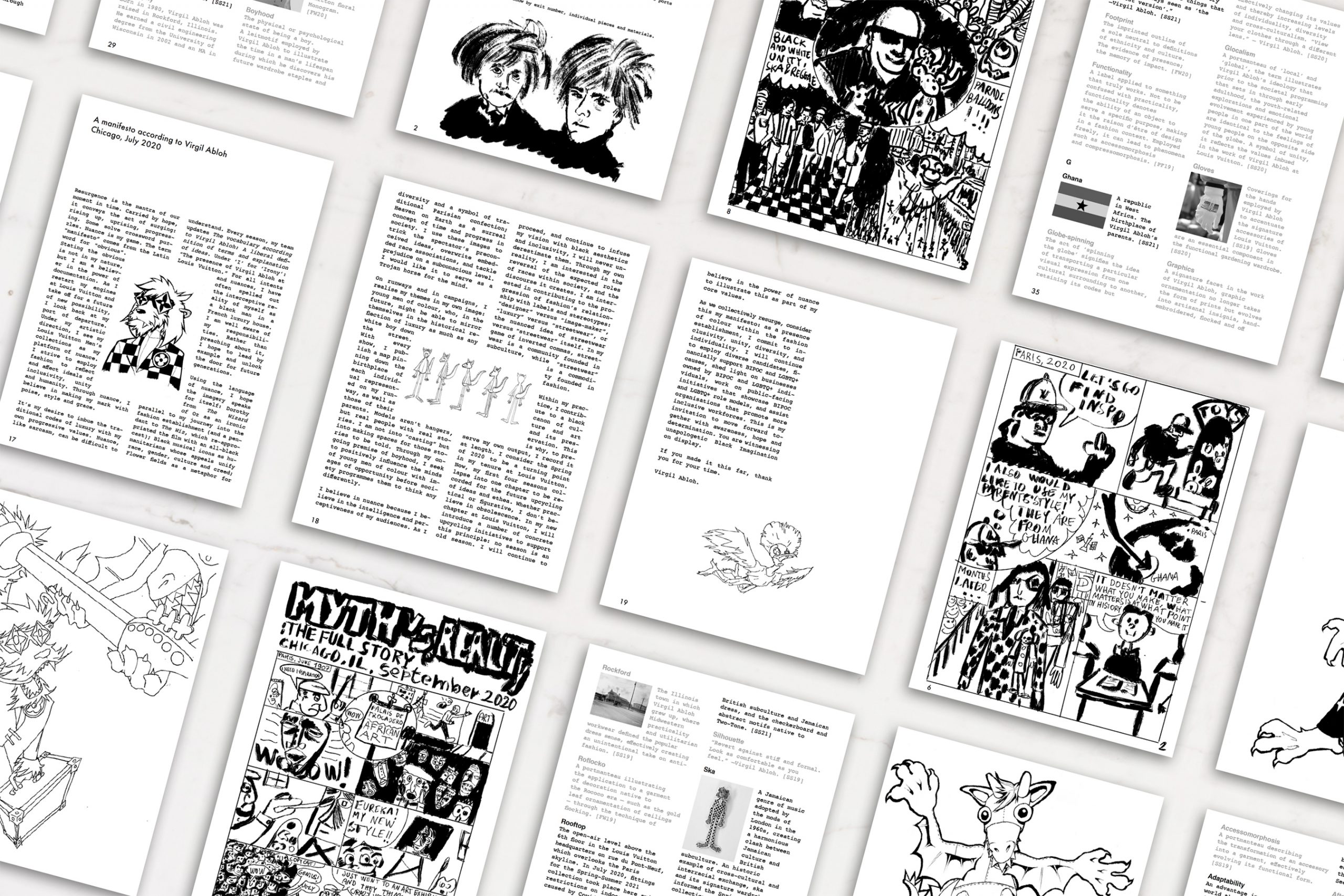

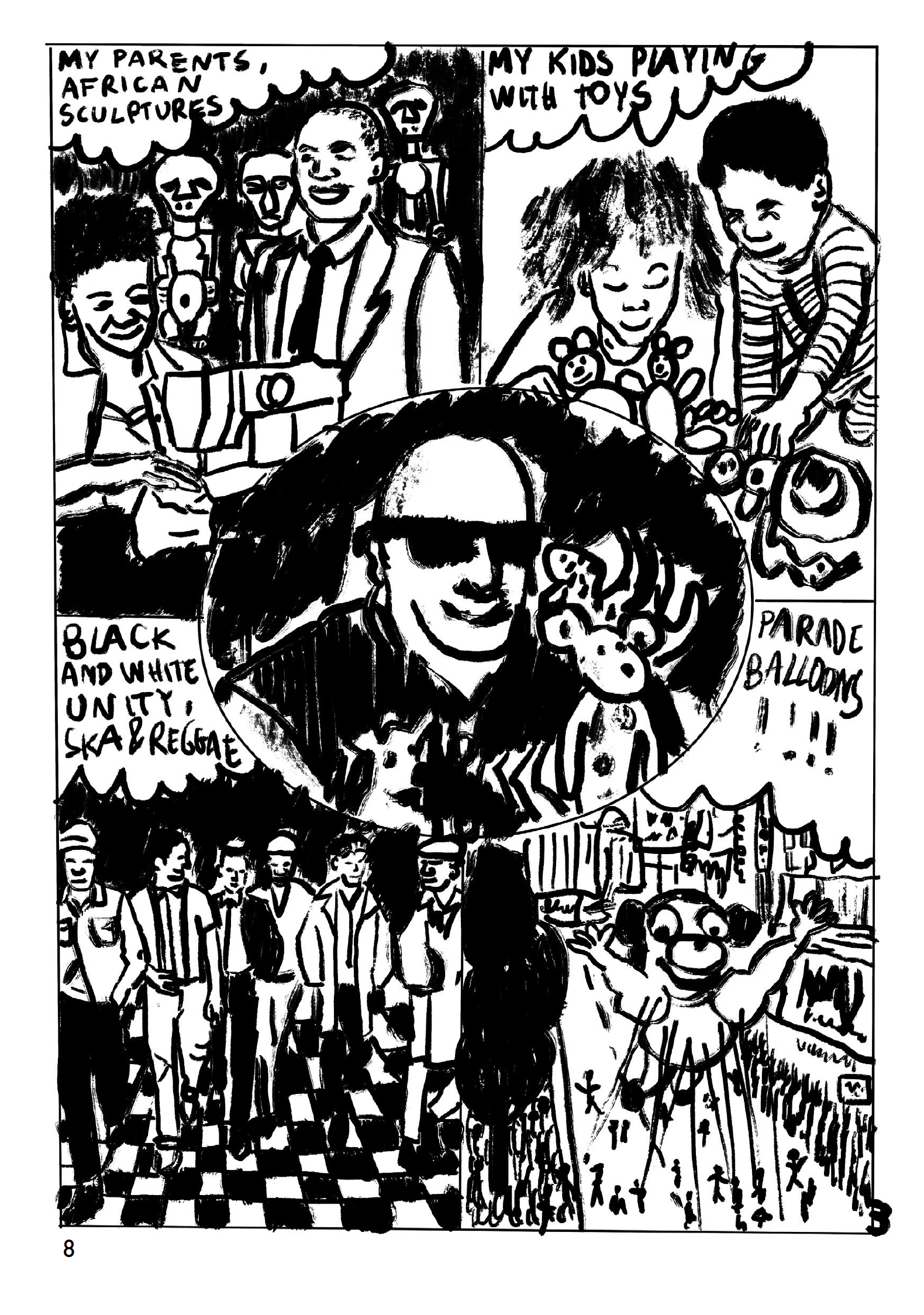

Clocking in at over 80 pages, the notes form a multifaceted manifesto, a thorough exploration and explanation of Abloh’s ongoing body of work for Louis Vuitton. In addition to the usual logistical trappings – descriptions of the pieces in each look, music and production credits – most of the document consists of several essays by Abloh, illuminated with visual work like sketches and comics, which express his goals and tools as an artist, as well as the responsibilities behind his unique role as the black creative director of a French luxury fashion house.

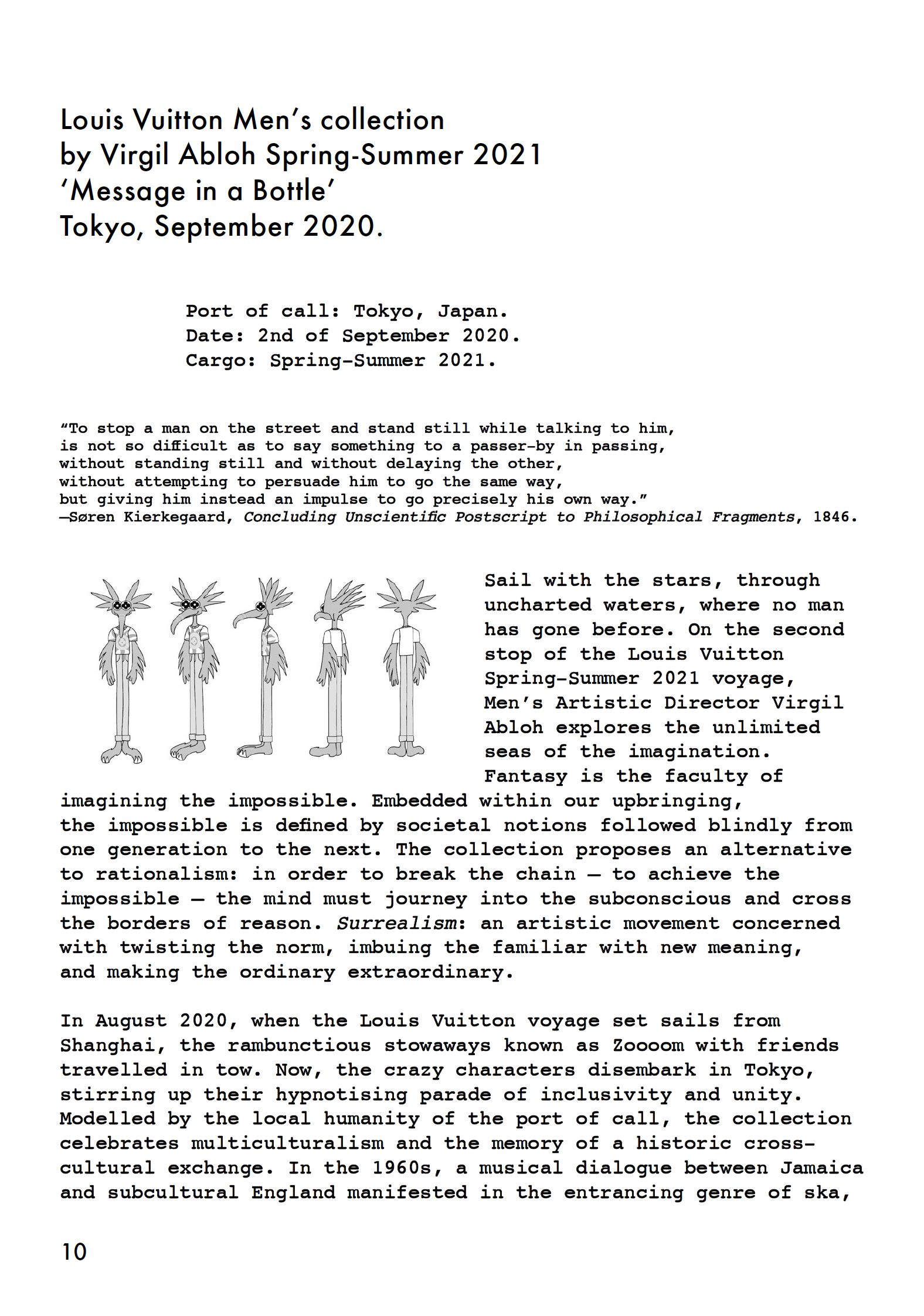

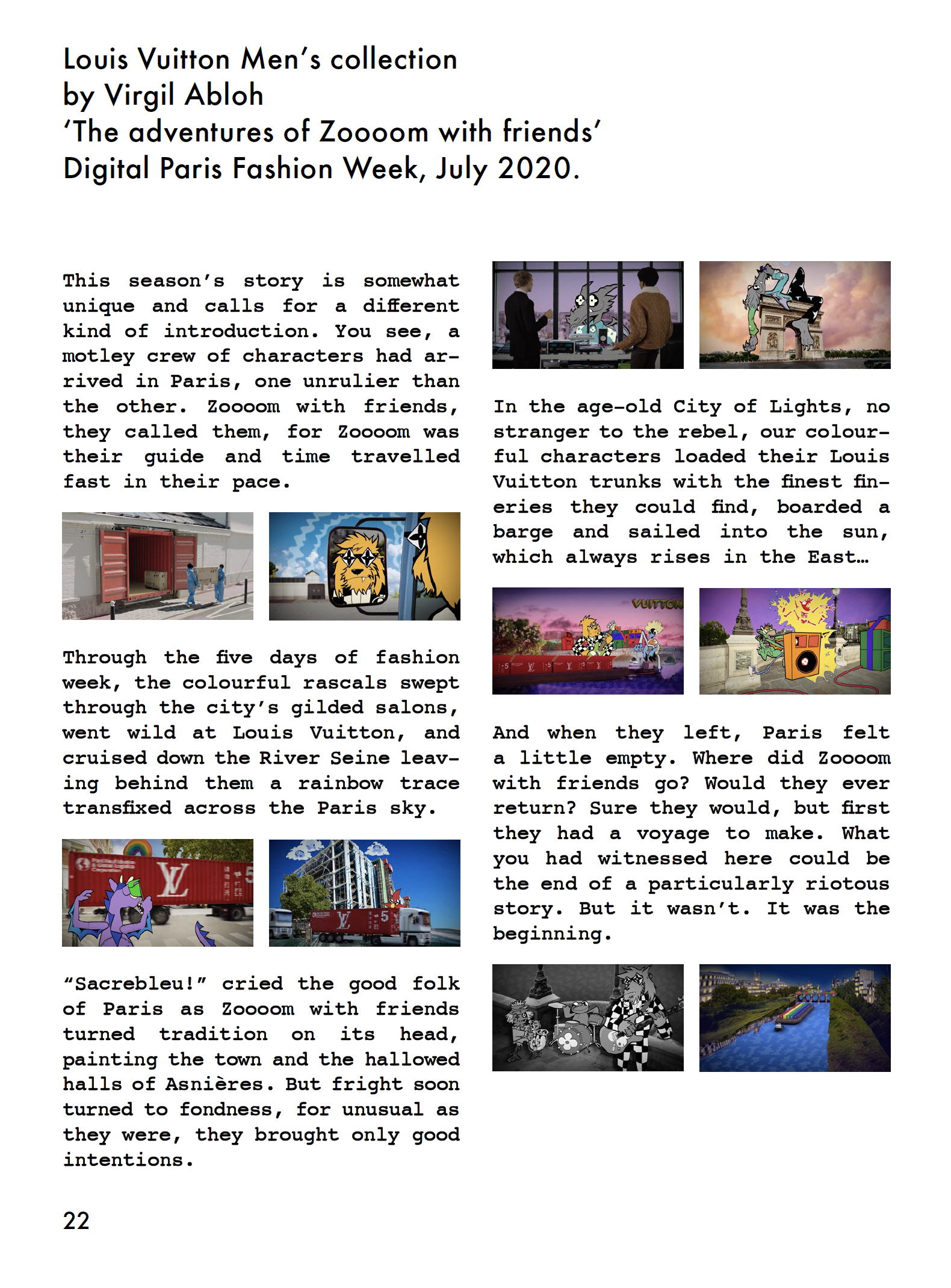

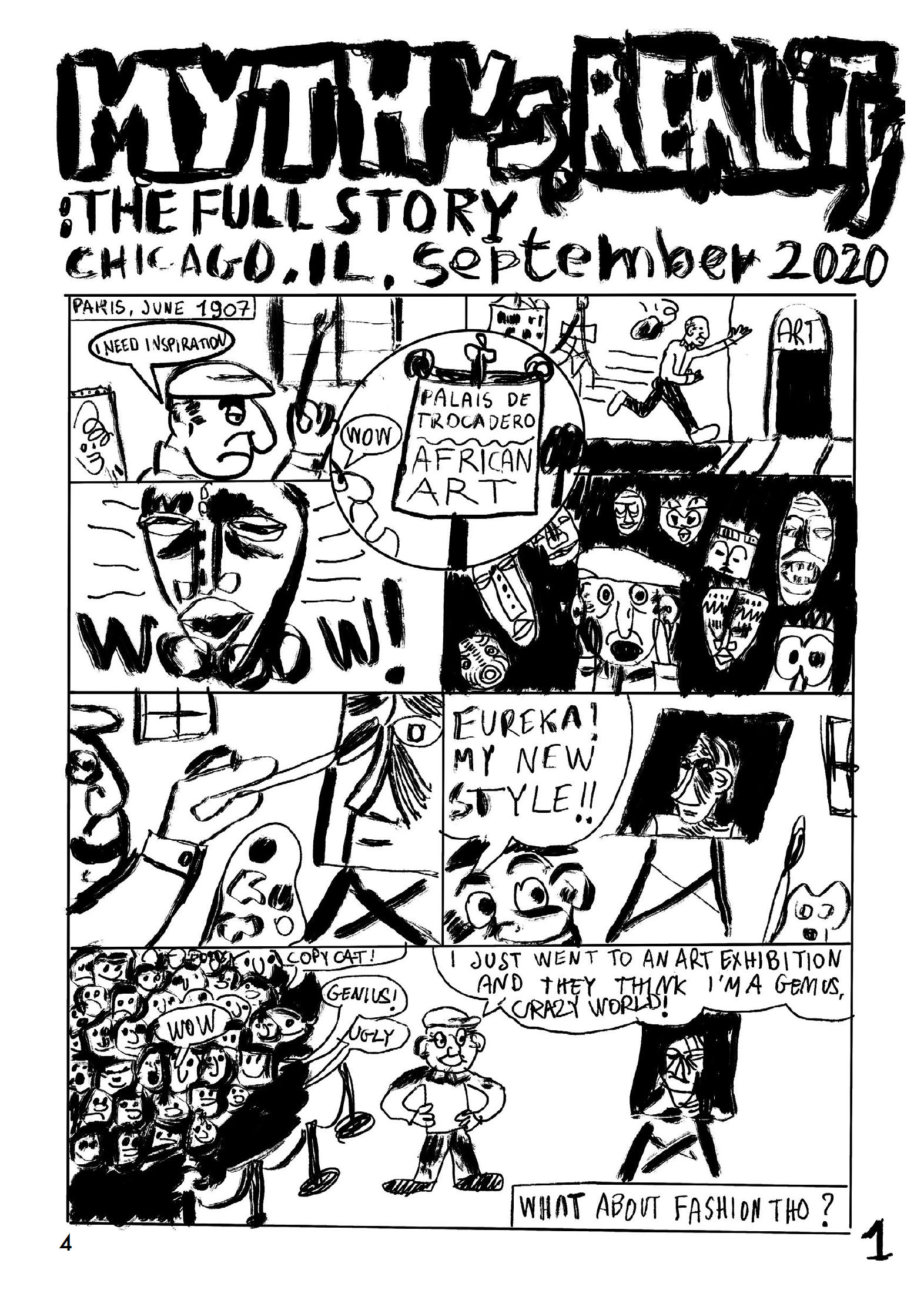

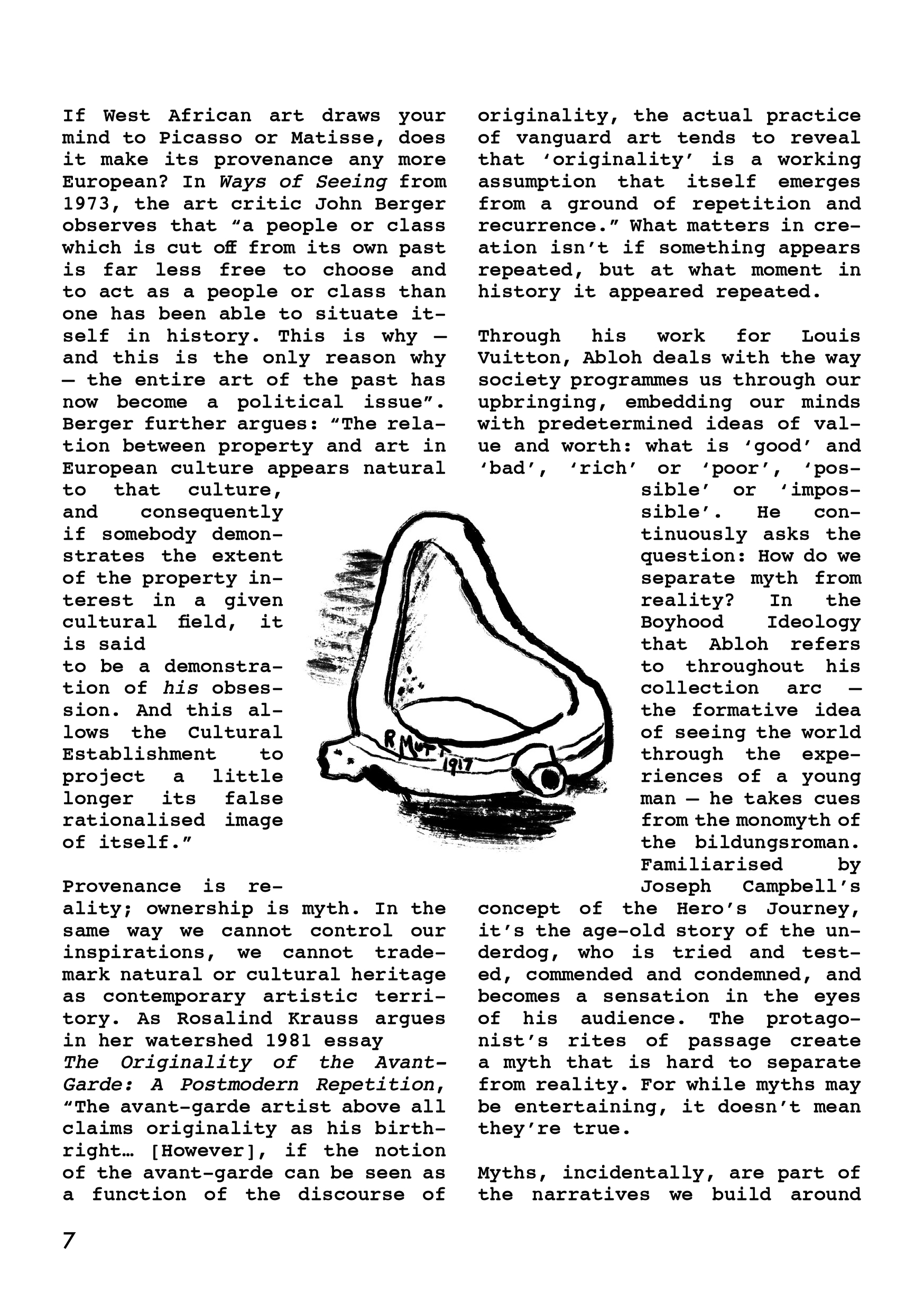

The first of these essays, entitled “Myth vs. Reality: The Full Story,” discusses the nebulous status of inspiration and ownership in art. Using as a touchstone his story of the inspiration behind the collection, which had its first genesis in explorations of his heritage through memories and conversations with his Ghanaian-born parents, Abloh seeks to transcend the false idea of ownership in art. Rejecting the apotheosis of originality in art, he instead celebrates the reality of inspiration, the endless self-informing cycle of receptivity and recreation. While it is somewhat dizzying to keep up with all the name drops, it is incredible to see the connections he makes and the cultural criticism he draws out of them: Picasso copying African mask, imported Jamaican reggae leading to the racial unity embodied in two-tone ska, Joseph Campbell’s hero’s journey expressed in Abloh’s own story and his thematic exploration of boyhood.

This discussion feels especially piquant in connection with the accusations of plagiarism that Abloh has faced. His detractors may spin it as a way to defend or justify alleged copying. But plagiarism takes idea ownership in art for granted – something can only be stolen if someone already owns it. Abloh’s more nuanced understanding of inspiration sees in the world of fashion what his heroes Duchamp or Warhol saw in the world of art: a symbology, a code, a language that repurposes already-seen symbols into new possibilities of meaning and experience.

But is it up to a creator to intellectualize their own creation? Should an artist tell their audience how to see? Especially within the fashion industry, which ultimately exists for the sake of the consumer, the purchaser, one cannot help but wonder whether this intrusion on the part of the artist between work and viewer is warranted, or worth it. Does the artist understand their work better than another person? Can the impact of a visual medium be pointed out in words? Again, does an artist own their art or the ideas it embodies?

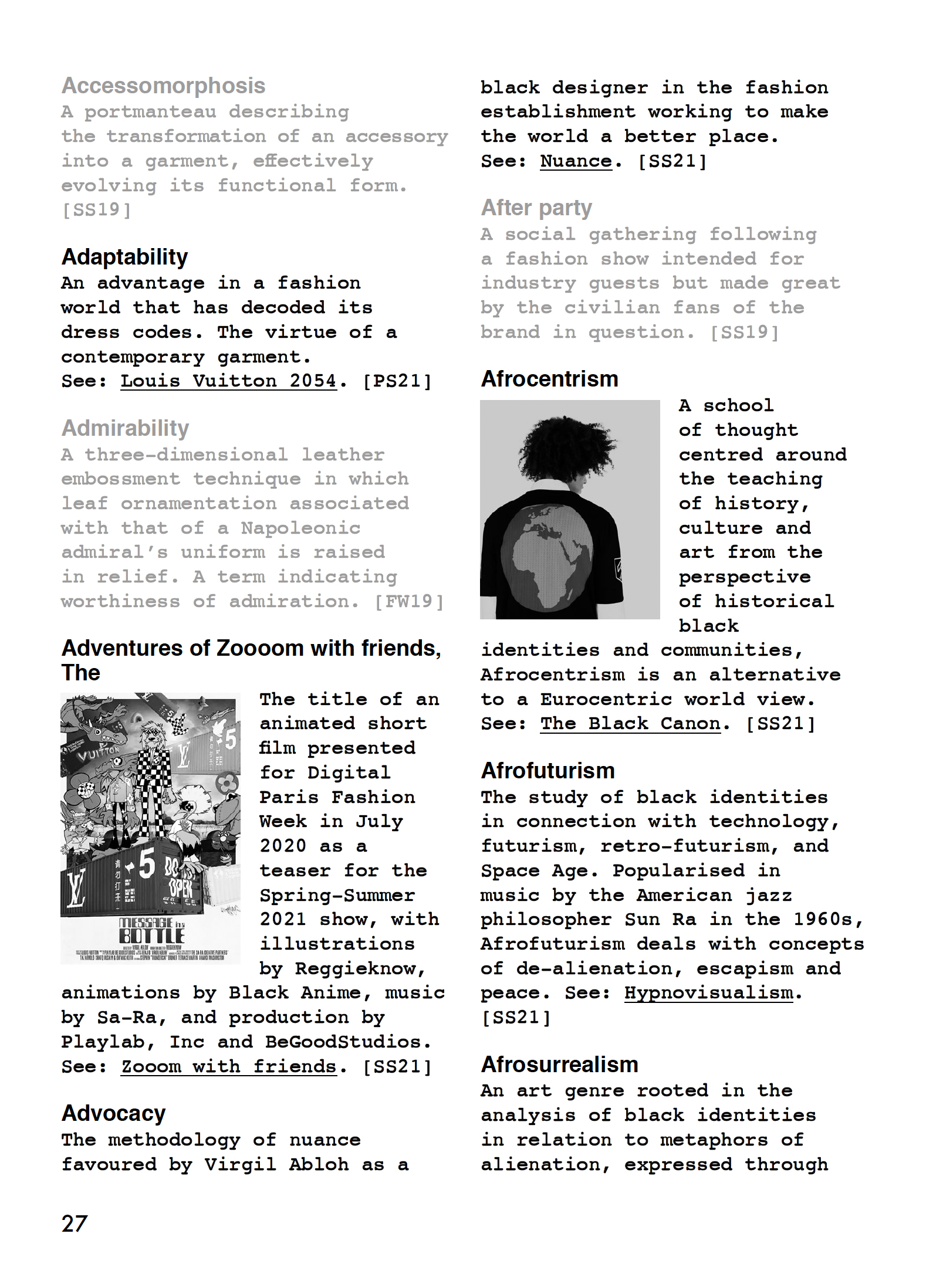

Considering these questions, the expansive “vocabulary according to Virgil” section of the notes is a strange and deeply intriguing inclusion. This is essentially a dictionary of the terms used by Abloh and his creative team while discussing and creating the collections. Industry standard terms like “bags” and “luxury” appear alongside neologisms like “invisippearance” and “glocalism,” as well as cultural touchstones like “Kente” and “Raphael.” But each word is defined by Abloh according to its place in his own artistic canon: surrealism, for example, is defined as “When streetwear imitates formal wear. When life imitates art. And vice versa,” and a tie is defined as “a symbol of the utmost uptight.” Taken altogether, the dictionary forms a comprehensive guide to Abloh’s creative world. But, as the product of an artist, the dictionary feels somewhat like a work of art itself. Though it is in a way ultra-transparent, our questions remain. It only gives us a framework through which to encounter the art and its ideas and problems, inviting us always deeper in.

The notes also reprint Abloh’s manifesto of Black Imagination, first published in July and embodied in his recent “Heaven on Earth” campaign with Tim Walker. This three-page document is essential reading for anyone interested in contributing to the progress towards meaningful inclusivity and representation in art and culture – which should be everyone. Abloh recognizes a responsibility in his powerful position as a black creative at the head of a French luxury fashion company – a major player in an industry which has exclusivity as its basis. He is dedicated to using this position for good. He is dedicated to creating art which uplifts and inspires young black men, and all people, to cast off this exclusivity and create a new consciousness of a present and future that is for everyone.

For all intents and nuances, I have often spelled out the interceptive reality of myself as a black man in a French luxury house. I am well aware of my responsibilities. Rather than preaching about it, I hope to lead by example and unlock the door for future generations… This is my invitation to move forward together with awareness, hope and determination. You are witnessing unapologetic Black Imagination on display.

— Virgil Abloh, Creative Director of Louis Vuitton Mens